Cadaqués is a bit of a tease. It’s the most inaccessible town on Catalonia’s Costa Brava but also its most seductively beautiful. Put the two together and you can see how it’s pulled off the trick of maintaining an air of a happening place where nothing happens, a place way off the beaten track that is a magnet for celebrities.

However, the pretty Mediterranean location belies a tough history. The character of the Cadaquesencs, as the locals are known, has been forged by piracy, contraband, isolation, bad luck and the Tramuntana, the maddening north wind.

The fates have not been kind to the people of Cadaqués. For centuries, in between being kidnapped by pirates, they made wine, but then the phylloxera epidemic in the late 19th century destroyed the vines. Undaunted, they replanted with olives but the trees were killed off by a freak frost in 1956.

After that, Cadaquesencs went into the tourism business, spurred on by their most famous son, Salvador Dalí, whose presence in the town attracted a roll call of artists and celebrities over the years, among them David Hockney, Richard Hamilton, Marcel Duchamp, Henri Matisse, Picasso, Federico García Lorca, Mick Jagger, Sting and Shakira.

Business was booming until the gods once more put the Cadaquesenc character to the test with Covid-19. This latest blow simply reinforced the local belief that, when disaster strikes, the only person you can rely on is a fellow Cadaquesenc, which has given rise to the town’s motto, Nos amb nos (Us with us).

Us With Us is the title of a book published in 2020 by the Barcelona-based writer Ryan Chandler. Part diary, part history, part travelogue, the quirky, offbeat approach of Us With Us is perfectly suited to its subject, a mix of anecdote, reflection, poetry and even the odd review inspired by TripAdvisor that combine to paint an affectionate and amusing portrait of a place the author describes as “pretty near perfect”.

Less a guidebook than a guide, reading Us With Us is like having someone take you gently by the elbow and say: “You see that over there? Well, there’s a story that goes with it.”

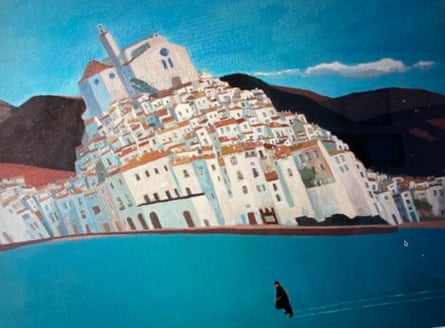

The book is illustrated by local artist Javier Aznarez, who worked on The French Dispatch, the most recent Wes Anderson movie.

Chandler quotes the 17th-century chronicler Jeroni Pujade, who describes the people of Cadaqués as “the most villainous and uncouth people on the whole coast”. Pujades summed up the local mentality as “we don’t want you and we don’t want to be wanted”, a precursor, perhaps, of the Millwall football supporters’ chant, “No one likes us, we don’t care.”

As there is only one road in and one road out and little space to park, in summer the police often declare the place full and turn people away on the edge of town. Of course, they could stop them before they begin the tortuous nine-mile (15km) drive over the mountain from Roses, but they don’t.

Before the road was built in the late 19th century, Cadaqués was only accessible by sea and it was plagued by piracy. Raiders would come and carry off a number of villagers and then demand ransom from the monasteries that relied on these local people to do the heavy lifting while the monks concentrated on God’s work.

Miguel de Cervantes, author of Don Quixote, was kidnapped by pirates near the town and was held in Algiers for five years before a monastic order stumped up the ransom. His kidnapper was Dalí Mami. “In a typical piece of fictional hocus pocus, [Salvador] Dalí claimed to have been a direct descendant of this famous pirate,” Chandler writes.

Cadaqués lives off Dalí the way Stratford-upon-Avon lives off Shakespeare, but not in a tacky way. Unlike Barcelona, which bulges with Gaudí souvenirs, the visitor to Cadaqués isn’t plied with Dalí ashtrays and aprons. In fact, in contrast to most of Spain’s Mediterranean coast, it’s hardly tacky at all.

Dalí is omnipresent though. Every bar where he supped his beloved pink champagne displays picture. In L’Hostal, now a restaurant but once a favourite celebrity hangout with a wild boho reputation, pictures of Gala and Salvador Dalí and Marcel Duchamp hang beside photos of Keith Richards, Sting and Shakira. It was here that Dalí once allegedly cajoled Jagger – some believe it was Richards – into an impromptu performance of Satisfaction.

There are more photos nearby in the Bar Melitón, and a plaque on the wall above the table where Duchamp liked to play chess. But Cadaqués isn’t content to live off Dalí’s image; it encourages art and artists, around 60 of whom live and work in the small town.

There are numerous galleries promoting the work of local and international artists, including the Galeria Cadaqués where Hamilton and Dieter Roth famously mounted what is considered the first exhibition to include a section specifically for dogs.

In the old town, where the steep and narrow streets are paved with jagged slabs of schist, laid edge on so that the donkeys don’t slip, people commission artists to paint something on their house, using as a canvas the small, metal electricity meter cover.

“What attracts artists isn’t just the light but the minerality, which is a combination of light and stone and water that creates a combination of colours which is unique, and you see that in the art produced here,” Chandler says.

The combination of this minerality with the weird light and cloud formations produced by the Tramuntana reveal that what we take as surreal was often Dalí just painting what he saw.

Incidentally, the name Cadaqués probably comes from càdec, (juniper), which grows abundantly around the town and on nearby Cap de Creus. Unlike Menorca, where British colonists taught the locals why God created juniper, there is no Cadaquesenc variety of gin.

Wealthy Catalans staked their claim on Cadaqués centuries ago, but it wasn’t until the mid-20th century that the Catalan bourgeoisie really set its eyes on the place and began to visit and buy up property. The town retains something of its hippy air, though these days it’s more crumpled linen than tie-dye T-shirts and, ultimately, wealth has inoculated the place against tack.

“If they haven’t sold out to tourism – and you won’t find a menu with pictures of bacon and eggs – it’s partly because the Catalan bourgeoisie and the people who have been coming here since the 1950s want to keep it the way it is,” says Chandler.

In addition to the locals, there are the new Cadaquesencs, people from Bolivia and Ecuador and elsewhere in Spain who work in the bars and restaurants. Or they did, until Covid shut everything down and put them out of work in 2020. The stoic spirit of the place has proved as contagious as the virus: and they too have shrugged off misfortune to face another day. Us with us.

Us With Us by Ryan Chandler is published by Barcelona Ink Books