The British film director Baillie Walsh is a man of many parts. He broke through as a director of music videos, initially with Boy George and then the Bristol trip hop collective Massive Attack, for whom he made the promo for the magnificent “Unfinished Sympathy”, from their era-defining 1991 album, Blue Lines. Later he directed memorable videos for Kylie Minogue, INXS, New Order and Oasis.

Walsh has made numerous award-winning commercials; acclaimed shorts; documentaries about music (Springsteen & I); and about filmmaking (Being James Bond: The Daniel Craig Story). He has written and directed a feature film, 2008’s Flashbacks of a Fool, starring that same Daniel Craig as a faded Hollywood star — narcissistic, hedonistic — forced to confront his past in 1970s Britain. (Don’t worry, Daniel, it’ll never happen!) For the finale of an Alexander McQueen fashion show, in Paris in 2006, he created a hologram of Kate Moss. I was in the audience for that show. It was beautiful, ghostly, and oddly moving.

Testimonials from prominent collaborators are not hard to come by. Moss, no slouch herself in this department, talks about his “sense of style and incredible taste.” Kylie mentions his incredible “capacity to convey emotion.”

“At his heart,” says Daniel Craig, “Baillie is a showman. The incredibly hard work that goes into all his projects is for one purpose: to move an audience, to give them a totally new experience, to affect them emotionally and spiritually and send them away with smiles on their faces.”

All of which could accurately be said of the 62-year-old’s latest project. It is perhaps his most high profile, and ground-breaking, to date. ABBA Voyage, which embarks seven times a week, including matinees, from the purpose-built, 3,000-capacity, spaceship-like ABBA Arena in Stratford, east London, opened in May to reviews that might reasonably be characterised as ecstatic. “Jaw-dropping,” marvelled the Guardian. “Mind-blowing,” panted the Telegraph.

I saw the show in early July. It is that rare thing: an event that exceeds its hype. It is, not to sound too fulsome, an astonishment. It is, also, a potential game-changer for the music industry and even for the idea of “live performance” — whatever that means after one has seen it.

ABBA Voyage has been described as a “virtual concert”. The former members of one of the most beloved and successful pop groups of all time — that is, Agnetha Faitskog, Bjorn Ulvaeus, Benny Andersson, and Anni-Frid Lyngstad — do not appear on stage in person. But they do appear. (ABBA disbanded in 1982; although they reconstituted the group five years ago, and have since released new music, it’s been over four decades since they gave a public concert.)

Instead of flesh and blood ABBA, the show is performed by life-sized, animated CGI avatars of the four members, restored by technology to their pop star primes. (ABBAtars, the producers call them.) But it’s also performed by the real ABBA, in the sense that they sang the songs, and danced the dances, in a studio in Sweden, and motion-capture technology allowed those performances — the singing, the dancing, even the chat between the songs — to be combined, on “stage”, with a live 10-piece band and a spectacular light show. The effect is uncanny. It’s not quite correct to say one feels oneself to be present at an ABBA concert in 1979. You are aware (just about, and sometimes not even) that it is 2022, and that in real life the members of ABBA don’t look like that anymore. But you are also conscious that you have entered another world — a virtual world, which is not to say you’re not in it — where you can be thrilled and moved by the power and beauty of some of the most familiar songs in the pop canon, those gorgeous, melancholic bangers that only those four people, together, could have made. The show might be virtual, but the feelings it evokes are genuine. I know, I felt them.

ABBA Voyage benefits from the talents of thousands of technicians and creatives: among others, a huge team from Industrial Light & Magic, the Hollywood visual effects powerhouse; the brilliant British choreographer Wayne McGregor; Swedish costume designer B Akerlund, whose clever modernising of the band’s stage wardrobes gives the show its convincing retro-contemporary feel; the live band; producers Ludwig Andersson and Svana Gisla. But if the Voyage is a trip, and it certainly is, then Baillie Walsh is the man at the controls.

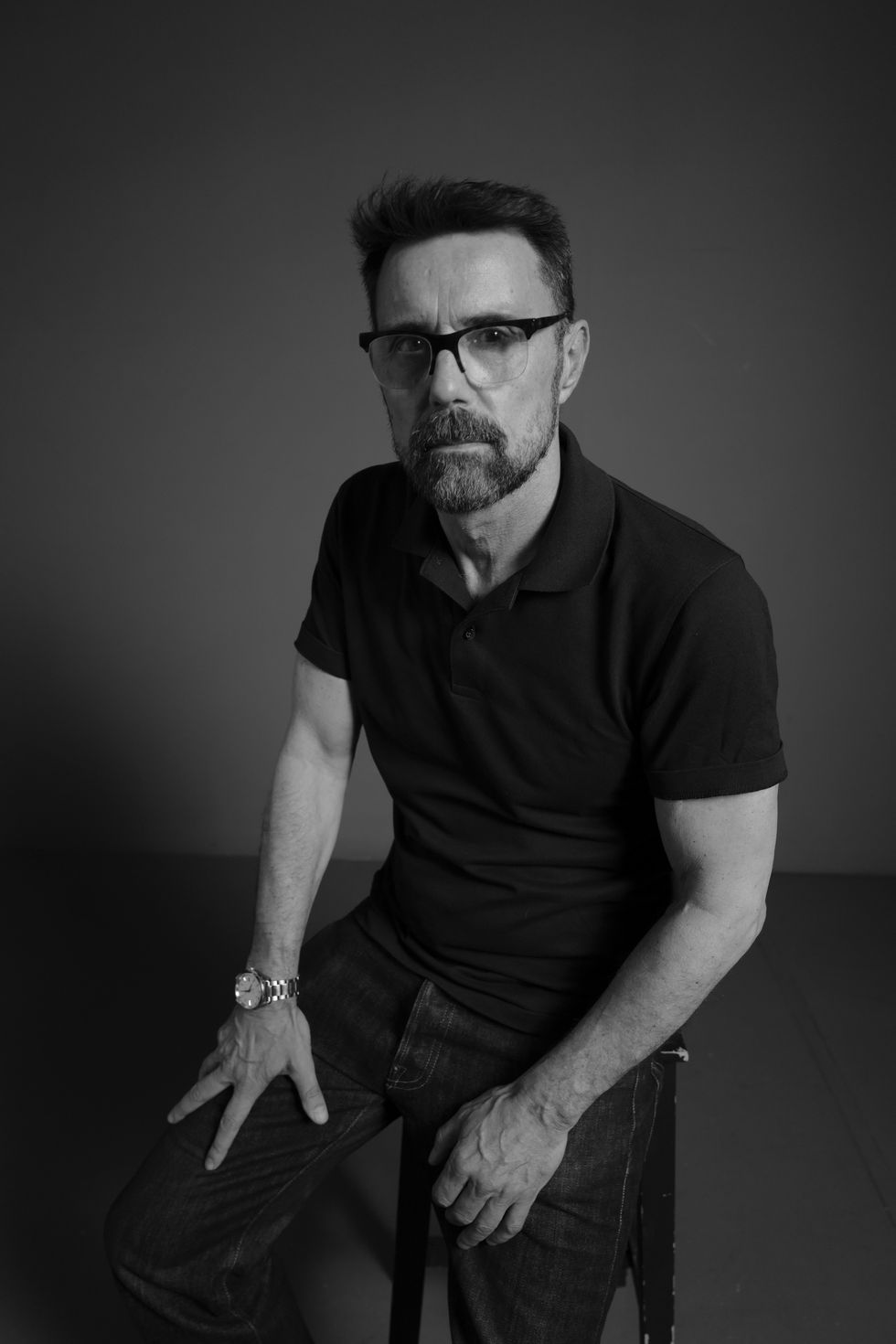

Slim, tanned, and handsome behind dark glasses — so youthful, in fact, that one wonders if this is really him, or a CGI avatar of his younger self? — Walsh arrives on the dot for his Esquire interview, at a hotel in Soho on a Tuesday morning (he lives just around the corner), orders a cup of English breakfast tea and settles himself at a quiet table. He talks for close to two hours, with barely a pause: about ABBA, avatars, his three decades and counting in film and music, and his own extraordinary backstory, from teenage tearaway to Top of the Pops and beyond…

The conversation below, as they say, has been edited and condensed. (A lot.)

Let’s start with how you got involved with the ABBA project. What happened?

One of the producers, Svana Gisla, I’ve worked with many times. I made Springsteen & I with her. A Kylie video, an Oasis film. And she was working with [Swedish director] Johan Renck on this project, and then he had this enormous success with [acclaimed HBO series] Chernobyl. So he saw a film opportunity and didn’t want to do this. [Raised eyebrow.]

Lucky for you!

Lucky for me. I had a Zoom call with Benny and Bjorn and they said yes on that call. That’s where it all began, three years ago.

How far developed was the idea when you signed up?

Johan had done a road map and there was a set list, which came from ABBA. But it was a very rough idea. They knew they wanted to make younger versions of themselves, that was ABBA’s idea. Whether that was going to be holograms or whatever, that was still up for grabs. So I came on board and there was a gradual process of: “What is this thing going to be?” The creative process on something like this is long, because it’s so big. You’re not doing one song. You’re asking, “What is this monster, what can it be?” So, my first job was to sit down and think about what I would want to go and see. I always played it like that. Then it was about talking to ILM about what would be possible. Ben Morris, the creative director there, was really brilliant to work with. And he loved the challenge, the idea of having life-sized avatars, and wanting to feel like they are really there.

Was there a Eureka moment where you said, “I know what this should be! It’s a live concert given by CGI performers!”

There was a few. When I realised, first of all, they have to be life-sized, that the audience has to feel like they are there. I knew it wasn’t going to be holograms. Holograms are so limiting, in the sense that you can’t light them. So then it was, “What does that mean?” We want life-size avatars but we want to see them really big, in detail, like you have at a concert, with the big screens. So we want those iMAG screens.

IMAG screens, for those of us who don’t know…

Those big screens, so when you go to see Beyonce, and she’s the size of a bean, you can see her close-up. But this isn’t the O2, where you’re so far away you can’t see or hear or feel what’s going on.

Your arena is much smaller than that.

That’s part of the success of the thing, I think, that arena. It’s really quite intimate. You can see every face in there, and the excitement spreads. I mean, there are many reasons for the success of this, so far. Lots of magic has happened. I’m a part of that, but the fact that it’s ABBA, the fact that they are still alive, and contributed enormously to this, and their soul is in this. The fact that they haven’t toured for 40 years, so there’s a great hunger to see them live, in whatever form. The arena, which is the perfect size, I think. And also so well designed, so comfortable. It doesn’t feel like you’re going to a horrible, beer-stinking arena, with turnstiles. From the moment you arrive, it’s already exciting. Like, “What the hell is this?”

Because it could have been a disaster.

Yes. It could have been a disaster, so easily.

Because it’s a very weird idea.

Yes! Totally. The whole thing I fought against is the tech, being led by the tech. The tech should be the least important thing. The important thing is the emotion. I want people to laugh, dance, cry. And you’ve got to be really careful with that. It’s multi-layered, because you are playing with the past, the present and future. And all of those big questions. You can’t throw that in people’s faces. The concert isn’t a big intellectual idea. And I never tried to intellectualise it. But I knew there were lots of big ideas under the surface.

There’s a lightness of touch to it that’s very appealing. And, of course, in the moment, unless you’re weird, you are not trying to deconstruct it. You’re just enjoying yourself. But afterwards I certainly was provoked to think about mortality, ageing, nostalgia…

But you can’t be heavy handed with those things. All I ever thought was, if I’m feeling emotion, if the ideas for presenting the songs resonate with me, then I’m on to something. Because I am the audience. So if it chokes me up, it’s going to choke everyone else up.

There are some people who feel that emotion stimulated by technology is somehow cheaper. That it’s inauthentic, in some way. That a concert given by avatars is fake.

The interesting challenge was: how can we fall in love with an avatar? That was the challenge. I wanted to do that, to fall in love with an avatar. And I did! The soul of ABBA is in those avatars. Their voices, those speeches, everything they say, the soul is there. It’s irrelevant that it’s an avatar. I mean, it’s helped by the fact that it’s ABBA, and their music is very emotive. That’s a massive advantage. If it had been Black Sabbath, it would have been harder to fall in love with the avatars. But ABBA’s songs, everyone has a connection to those songs. They are part of our DNA. They are part of who we are.

Talk a bit about the process of creating the avatars. How did you do it?

Basically, we were in a studio in Sweden for five weeks, with ABBA. And we filmed them with 160 cameras, in motion-capture suits. We went through the whole set list, and more, and they performed those songs for the cameras. It was a very bizarre, amazing experience. You’re in this kind of NASA-style studio, with monitors and cameras everywhere, and 100 people in there taking all the data. A very bizarre situation. As individuals they are really lovely people, but the moment you bring those four people together, something happens. This strange alchemy. Which is a really rare thing. I mean, I’m sure it happens when the Stones come together, or when the Beatles came together. This extraordinary energy. I don’t want to get all woo-woo about it. But it’s perceptible. When they came together on that stage, on the first day, it’s goosebumps. It’s a magical thing. And that’s why I feel so lucky to have got this gig and to have been able to do what I’ve done, with ABBA. I can’t think of another band who would be better than them for this project. I’m spoilt now. I’m fucked, really. I’ve made something that hasn’t been done before, which is a really rare opportunity. How am I gonna top this?

That was going to be my last question. I was going to leave your existential crisis for later.

Thank you!

Now that you mention it though…

I haven’t had time to think about it. I’ve been on this project for three years and I’ve had four days off. I finish on Thursday and go to Iceland on Saturday.

For a holiday?

I’ve got a house there. This’ll be the first time I’ve been in three years, but it’s where I go and spend time alone. I look at nature, and look at sky, and go fishing, and it’s good for my head. I’m not quite sure how it’s going to work this time. I’m expecting an enormous crash.

Clearly, you’re going to have a terrible time.

Terrible! It’s going to be awful. No, but I have just had the best job that I’ll probably ever have. I hope that’s not true. But I think it’s the best job I’ve ever done. I’ve worked for a very long time and there are peaks and troughs. But the scale of this is what makes me most proud. It’s big!

It feels game-changing in many ways, and it does open a Pandora’s box. What does this mean for live performance? What does it mean for musicians? For audiences? Could you do it with the Stones? What would it mean if you did?

Of course you could. Charlie [Watts] isn’t around, so you’re going to miss that. But yes, you could.

You couldn’t do it with Prince, for example, presumably because you can’t do the motion-capture part?

No, but you could do it. Especially with the way technology is moving. You could do it posthumously. But one of the things that is great about what we’ve been able to do is, we’ve been able to update ABBA. It’s not just nostalgia. It’s past, present and future. It’s about being able to reinvent ABBA for 2022. It’s not about recreating the 1979 Wembley concert. That wouldn’t be interesting. You can watch that on YouTube.

What about the Stones, then? Would it be desirable to do this with them?

That’s not for me to say. It’s not desirable for me. Because I think I’ve had the best band to do this with. The Stones have been on tour since year dot. They’re still on tour now. Of course, it would be exciting to see Mick in his heyday. But Mick is still so great live, at 78. Unbelievable. Not only running about the stage, but singing at the same time! I can’t walk and speak! He’s still doing it, and that’s what you want to see, with the Stones.

There are ethical concerns, too. Especially the idea of doing it with dead people.

Well, Whitney! They made a hologram of her. I didn’t see it. I saw bits of it on YouTube. But the first word that comes to mind is “grotesque.” Because that’s just a money-making exercise.

Is this going to be rolled out to other countries?

Yeah, I think so. You could do Vegas, you could do New York.

Will you be involved in those?

I hope so. This is my baby and the idea that someone else is going to take it and remodel it in some way that I found really annoying… I hope I am involved. Maybe we can add something to this that will knock people’s socks off even more? Because we do have the ability to change the show. We recorded more songs, filmed more songs. Maybe we can improve it?

One more question on the ethics of it. If a contemporary artist came to you, say Beyonce, and asked you to do the same for her as you’ve done for ABBA, to put on a virtual Beyonce concert that could play every night of the week in cities around the world, forever, and she need never leave the house again, would you? Because that idea worries people who love live music.

Yes, but I think they shouldn’t worry. Because first of all, Beyonce loves to perform. She’s not going to stop, because she is a genius performer. That’s who she is. That’s her being. And I don’t think this is going to replace anything. It’s part of the entertainment world now. But people want to see live concerts, and people still want to perform them. You think Bruce Springsteen is going to stop touring because he could do a virtual show? His life is touring. And most of those people who perform, it’s who they are. The Stones don’t want to sit at home with their feet up! They want to be on stage. They love that adoration. Who wouldn’t? 100,000 people screaming that they love you? Gimme more! So I don’t think people should be worried. They should be excited. And it’s not just music. The idea of how theatre can use this. The immersive quality of it. That thing about not knowing where the real world ends and the digital world begins. All that is really interesting. I want to see what other people do with it. I want to be excited and blown away and confused. I really look forward to seeing where it goes.

You live round the corner from here. Did you grow up in London?

I was born in London and then moved to Essex when I was young. And brought up there, all around Clacton-on-Sea, those terrible seaside towns. Working on Clacton pier, being a bingo caller, that was the start of my showbiz journey.

Do you come from a showbiz family?

No. My mum was a pharmacist, my dad was a rogue, a gambler, with all of the disaster that brings. And my mother brought up three kids on her own, pretty much. I have an older brother and a younger sister.

What kind of boy were you?

I was a rogue, too, a runaway. At the age of 14 I ran away for a month, and was in London with my friend. Can you imagine?

What were you doing?

Stealing. Shoplifting from Portobello antique shops and selling it on the Market. I was a terrible, horrible child.

Where were you living?

At the Venus Hotel on Portobello Road, with my friend’s sister. She had two children and she lived in one room in the hotel, and we lived there too. But I got caught, in the end, and put into a home, a halfway borstal. And that fixed me. I was only a couple of weeks but it scared the life out of me. And then I decided, somehow, I was going to go to art school. I was always in trouble at school, for fighting, but this teacher picked up on the fact I had some kind of talent and nurtured me, and I got into Colchester art school, doing graphics.

When was this?

I was there from 1976 to 79.

During punk.

Yeah. But I wasn’t a punk. I was more of a soul boy. It was [famous Essex soul club] Lacy Lady for me.

And after you finished art school?

Well, I didn’t want to be a graphic designer. I didn’t want to be trapped behind a desk. It wasn’t for me. Back in those days you didn’t think about a career. I just went on the adventure. I became a coin dealer, by accident.

How does a person become a coin dealer by accident?

It was when there was a gold rush on. We used to set up in hotels and buy gold and silver by weight, and the person whose business this was, was a coin dealer. I knew nothing about coins. But the great thing about it was, we travelled all over the world. And of course, I’d never travelled. I was 19, 20, and I moved to California. And I got bored of that after six months, came back to London for a holiday, and I got a job dancing with the girls at the [legendary Soho strip club] Raymond Revue Bar. Basically, erotic dancing.

Hang on. You need to explain this.

OK. So, I was staying in this really crummy flat where there was newspaper on the kitchen floor. And I saw an advert there for people willing to appear naked on stage. And I thought, “I could never do that.” So: great, you’re gonna do it. Things that are fearful, you do them. I love that. That’s the whole thing about being creative. I love to be shit-scared. So I called up and I got the job.

Did you have to audition?

Yeah.

You had to take all your clothes off and dance around?

The first audition was just take your clothes off and stand and pose and turn around for the choreographer, Gerard. And I later went to visit him at his flat on Charing Cross Road. And there’s this bay window that looks out onto the National Portrait Gallery, the Garrick Theatre, the neon lights, I’m 20 years old, and it’s like, “This is the best flat in the world!” And the dancer I took over from had the flat upstairs, so he moved out and I moved in, and I still live there today. I’ve been there 40 years, my whole adult life. And I think I might stay.

So the Raymond Revue Bar…

My first taste of showbiz!

It’s a load of girls getting their kit off on stage and…

Yeah, you’re a prop. You’re naked, and you have simulated sex. There’s a scene. You’d come out and pretend to play tennis, and then the music would change and suddenly it would be a sauna scene, and there’s a bench, and the lights change and you’re pretending to throw water over the girls… It was a real experience. I never got used to it. The audience are men. They want to see naked girls. They’re not happy when they see you up there.

How long did this last?

About a year? And while I was working there, I met Antony Price, at the Camden Palace. And he became my first boyfriend.

And Antony Price, for those who don’t know, was an important fashion designer…

The designer for Roxy Music. He was a real hero of mine when I was a kid. When I was 14. All those album covers, all those clothes… And because I was a dancer, Antony asked me to stage his fashion show, at the Camden Palace. So at the age of 21, I did that. At the time it was a really big deal.

Your first directing job.

Yes. I learned so much from that, and from him. His style and taste and knowledge of film and music. Just an unbelievable man.

Was that the end of your career as an erotic dancer?

Well, then I became a model. That was great. Modelling gave me the chance to try lots of things and meet lots of people. And I was successful. Modelling was a different world then. I made a living from it for a reasonable amount of time. I enjoyed it for a while, then it gets dull. It becomes a job. The glamour wears thin. And then I was getting dancing jobs as well. You know, dancing with Bananarama.

I don’t know! Tell me about dancing with Bananarama. When was that?

1987, I think. I got a call from [now famous Strictly judge] Bruno Tonioli saying, “Do you want to dance on Top of the Pops?” So, I went, “Lifelong ambition!” So, me, Bruno, and his boyfriend then, Paul, were the backing dancers for Bananarama on Top of the Pops.

Which song?

“I Heard a Rumour.”

I’ll look it up on YouTube.

You should. [I did. The trio certainly carry off their cycling shorts.]

When does the film directing start?

At the age of 25 I saw 1900, the Bertolucci film. And that blew my head off. I just thought, I want to do that.

What was it about that film?

Just the epic quality, the skill in the filmmaking, the beauty, the emotion, the characters, the storytelling… it had everything. Now, I’m never going to make a film like 1900, but I started making little films with my mates. Super 8 and video cameras. And then I made one video in 1987, with [performance artist, nightclub legend, fashion icon] Leigh Bowery, who was a great mate.

You knew these people through nightclubs, that amazing scene in London in the 1980s?

Yes, exactly.

Were you a Blitz kid?

No, after that. Taboo, Leigh’s club, in Leicester Square, that was the best for me. That was the summit of my nightlife.

It’s always striking, that so many influential creative people came from that very select, underground world.

Everybody was there. [Film director] John Maybury was my boyfriend at that time. I went out with John for 17 years. I learnt a lot from him. They were amazing times.

All the most important future fashion designers and photographers and artists and filmmakers and pop stars in one room in London, dancing. It's hard to imagine this happening now…

Because of social media, I suppose. People are on their phones all the time. They don’t go out anymore. It’s one important point about the ABBA show [which insists the audience switch off their phones.] I had to really fight for that. Because otherwise they spend the whole concert filming it.

People can’t process a show, or anything else, unless they mediate it themselves.

It’s just like, “What the fuck are you doing?” It’s such madness.

You wonder what people think they are going to do with all that footage. What’s it for?

I know. Is it about ownership? “Look, I filmed this!”

So the ABBA phones policy came from that?

Yes, for all those reasons. But it was a very contentious idea. Lots of the suits, they disagree. They think that’s what everyone wants. I said, no, nobody wants that. They want to experience the show. They don’t want it ruined. The moment you put a phone up, everything’s abstract. You’re not in the moment. It’s insane. Stop!

So back to the career. You’re making a film with Leigh Bowery.

Yes, I wanted to make a pop video. So I made a track, a series of samples, called “Boys”. And Leigh is the lead in it. And Boy George saw it. This was ’87. And he asked me to make a video for him. And that was it, I was away. I made one called “After the Love”, and then “Generations of Love”, in 1990. That changed everything for me, because Massive Attack saw it. Basically it was the story of Soho, at that time. Thatcher had been in power for a long time. I was just seeing homeless people everywhere. It was really bad. So I got all my mates dressed up in drag, as prostitutes. Leigh styled it. I made a porn film, so we could project it for a scene inside one of the porn cinemas. I went and presented it at Virgin, and persuaded them. They paid the bill. And the next week I got a letter saying if you EVER show this film anywhere, we’ll sue you. But I got away with it. And it was a calling card. I still think it’s my best video. I have such fond memories of it.

And that’s what got you Massive Attack.

What a gift! To be given that album. I got the first four singles. Goosebumps, immediately, “Unfinished Sympathy” is one of my favourite songs ever, still. So beautiful. Extraordinary. And because they were the biggest band of that year, and I was associated with them, suddenly I had a career. Hate that word, career. I had the possibility of a working life, of becoming a director, I was up and running.

"Unfinished Sympathy" was such a distinctive video: one take, [the singer] Shara Nelson walking through Downtown LA, apparently oblivious to everything around her. And that’s it.

It hadn’t been done before. I wanted to challenge myself, I wanted to be scared. “Can I do this?”

It’s the antithesis of one of those videos that’s all about trying to sell the image of the star, the band.

But the song gave me this. That thing of when you are really hurt, and you are walking down the street and you are completely and utterly within yourself. You are not noticing anything that’s going on around you. We’ve all been there, right? Just destroyed by love. I wanted it to be that unbroken thought. This inner voice. That came from the music. But at the same time I was very aware that I was going against the tide, which I knew was a really good idea. Always a good idea. Because every [other] video at the time, it was [director] David Fincher, and it was all about fast-cuts.

His stuff with Madonna?

Yeah, it was all fast cuts. Make it as bright and shiny and fast-cutty as you can. And I’m sorry but “Vogue” is a fucking genius video. And David Fincher did it very well. But we went against the grain, made it really gritty. And Massive Attack’s music always smelt American to me. It sounded so big, so epic. I really wanted an international visual language for them. Take it away from Bristol, from the UK. So Downtown LA. In fact, the first video I did for them was “Daydreaming”, which I set in the Deep South. But yes, opportunities were coming thick and fast at that time.

You were very successful for a while.

Yeah. I only made thirteen videos. And then the world changed, budgets shrank, the demands from the record companies grew. And I thought, if you want me to basically make advertising, I’ll go off and make a ton of money doing that.

Which is what you did.

It’s what I did. I don’t say I made a ton of money but I earned a living. And the great thing about advertising, as nasty as it can be, is that you get to hone your craft. You’re filming, you’re on a set, you’re working with people. That’s really important, because making films is next to impossible, right? I’ve never been lucky at that.

Was it always in your mind, throughout the Eighties and the Nineties and beyond, to make a feature film?

Always. Always to make movies. And I wrote many and nearly got them made and spent years trying, as you do with films.

And, finally, you got there, with Flashbacks of a Fool.

Yes. And there were really good things about that and really bad things about that. The great thing was, I wrote that for Daniel Craig before he was Bond, right? We’re mates. And he still wanted to make it after he became Bond, which was wonderful. Because that meant all the effort that I’d made when I tried to get it made before he was Bond, and failed, had not been wasted. When he became Bond that gave him enormous power. He could get anything made. And he was generous enough to sprinkle some of that glitter on to me, and to allow me to make that film. The trouble with that is, that this small art film is then sold as a Bond film. Which is a disaster. Because if you deceive an audience, they don’t like it. You can’t sell candyfloss as popcorn. People want to know what they’re buying, so when it’s released as a fucking Bond film, and it’s a small little art film that should be in two cinemas and possibly grow from there, it’s a disaster. And critics don’t like it, either. No one likes it. I still have a fondness for Flashbacks, but I was really hurt by the response to it. When you put that much heart and soul into something, and you have a joyous time making it, and it’s received with a shrug of the shoulders and a “whatever”, it’s tough. The opposite to what the ABBA thing has been. This is all five stars. Every review. I’ll never have reviews like this again. But the reviews for Flashbacks knocked me, they knocked my confidence. I doubted myself. I felt misunderstood. It was really, really annoying. “No one understands me!”

How did you recover from that?

Well, cut to two years later, someone sends me a link to Flashbacks on YouTube and I read the reviews on there. It blew me away. Floods of tears. Because what I wanted, it did happen, people did get it. So I’m not saying the film is a success, or good. But the response I wanted did happen, and that was a beautiful thing. So I’m really fond of the film. I know it’s flawed but I think there are great moments in it, and I learnt from it. I would love the opportunity to make another feature film. I still have that ambition. Even though film now, somehow, has really lost its lustre. It’s really shocking.

Why is that?

The demise of Weinstein, I think. It died with Weinstein. It was dying anyway, but that finished it off. Because when he was at his pinnacle, the monster that he was, but how fucking great were the films? And the stars! Now, apart from Tom Cruise, there are no movie stars left.

The independent film scene in the Nineties and Noughties was rocking.

It was so exciting. And it’s gone. It’s such a tragedy, obviously, that Harvey was such a monster. Not only for the obvious reasons, for the people affected by his behaviour, which is a tragedy. But also for cinema. Now, the world’s a different place. That was the zeitgeist, that was the time. And now cinema is not nearly as interesting as it was. So yes, I do want to make films, but the idea of making an arthouse movie and going to Poland to show it at a fucking festival, is not interesting. I want people to see it!

What about TV, where all the action is? Is that appealing?

Yeah, I have a TV series I’d love to make. It’s called Pussycat Lounge, based on my year at the Raymond Revue Bar. Set in that period. [Production company] Tiger Aspect had it. That didn’t go very well. Got it back from them. And right now no one is interested. I think that because I do so many different things, it’s kind of hard to place me.

You’re a victim of your own versatility?

Maybe. I always try to treat everything I do with the same enthusiasm. I don’t think there’s a difference between all these things [videos, and films, and shows]. But people in Hollywood don’t think like that. They want you to repeat everything. We all know that.

They would rather you did another ABBA Voyage than made a TV show.

Exactly. Although having said that, I do love putting on a live show, seeing people’s reactions, having an adoring crowd. And it also seems to me that this golden age of TV is coming to an end, too. Five years ago, every director wanted a TV show. Now it feels like that’s dying. There’s too much stuff, right? I’m just overwhelmed when I go on to Netflix. That was the great thing about growing up in my period: you had to wait for the single to come out. You had to wait for Top of the Pops on Thursday, to see that performance. Now we’re just fucking overwhelmed.

Not least by social media. We’re all on our phones.

I think social media is a terrible thing, I don’t do any of it. It’s just noise. I think it’s the least creative thing ever. And if I was on it, because I’m obsessive, I would want to do it well, and that’s a full-time job. It’s all-consuming. I wouldn’t have made [the ABBA] show if I was on social media. I wouldn’t have had time!

Also, don’t know about you but I have never been moved by a post on Instagram. I have never been enlightened by a Tweet. These aren’t media where we can really connect deeply with other people.

No! It’s impossible. I’m suspicious of all posts. They all have a motive. They aren’t gifts. They’re not about anything but the person who sends them. It’s all about you. And, actually, fuck off!

A lot of stuff seems to be dying. I saw Glastonbury on TV. It was Noel Gallagher, Paul McCartney…

And Diana Ross! Fucking geriatric. Torture, it was torture! Although I had to watch the Pet Shop Boys, because I know them. And you know what? They were fucking great. Like, “OK! Now we’re cooking!”

The risk is, we end up sounding like a grumpy old men.

But I am! And it’s hard to be excited about anything when there’s too much stuff.

Which brings us back to the ABBA show.

It’s exciting because it doesn’t feel like anything else. It’s different. It’s a miracle! Seeing the joy drip off the walls of that arena, it’s unbelievable.

So what’s next?

A holiday. And because I’ve thought of nothing else for three years other than ABBA, I need to take a breath, and be quiet, and think. Like I was saying, I’ve been really spoilt, with this project. What’s next? The thing is, in a way it’s not for me to say. All these opportunities that have come my way, people have given them to me. A lot of them, I haven’t gone searching for them. So what’s next is, wait for the next job to be offered.

That sounds both admirably zen, and also a little terrifying. What if nothing comes along?

Something always has. Alex, I’ve done this for 30 years or more. There are times when I’m really popular, and times when I can’t get arrested. That can go on for years. There have been times when I haven’t worked at all for two years. Because I couldn’t get a job. But that’s the nature of my business. You’re in and out of fashion. You do something that gets lots of attention and you’ll get work for a couple of years, maybe. And then it stops again. You do the best you can. You might do quiet work for a bit. A commercial that’s only shown in China. To earn a living. And you wait for an opportunity.

So now…

For a couple of weeks, I’ve got opportunities.

And you’re going to disappear to Iceland?!

They know where to find me. But, no, the ABBA show is going to roll out all over the world, right? That’ll give me some longevity. And by that point I’ll be dead anyway. So, I’m not fretting.