You’ve probably heard of Zlib, but even if you haven’t, you’ve almost certainly used it.

Zlib’s unashamedly 1990s-style website describes the product as A Massively Spiffy Yet Delicately Unobtrusive Compression Library (Also Free, Not to Mention Unencumbered by Patents).

Data compression software (and, of course, the matching code to decompress it later) has always been handy to have around, as anyone who has ever used software such as PKZIP, WinRAR, 7-Zip and any of a great number of archiving tools will attest.

As you can imagine, the primary purpose of data compression is to save space, such as reducing the storage capacity needed for backups or cutting down on the bandwidth used for data transfer.

Often, however, despite the computational overhead added for squashing and expanding the data before and after storing or sending it, compression saves time as well as space, simply by reducing the amount of data that needs to be shuffled back and forth between a fast storage location such as RAM (memory) and a slow one such as disk, tape or network.

An internet standard

Zlib’s compression algorithm is known simply as DEFLATE.

Although the algorithm was originally part of a patent for use in the commercial compression software PKZIP, it was adopted as an internet standard in RFC 1951 DEFLATE Compressed Data Format Specification version 1.3, published in 1996.

RFC 1951 notes that, despite the patent on PKZIP’s version of the process, “[t]he format can be implemented readily in a manner not covered by patents.”

Ironically, perhaps, Zlib and its companion tool gzip (which compresses individual files using the Zlib algorithm) are probably best-known to users of Unix/Linux, because they were introduced as a replacement for the once-ubiquitous Unix tool compress, which performed a similar function with a similar sort of algorithm.

But fears over compress getting caught up in patent arguments meant that the Unix community sought an unencumbered equivalent that wouldn’t suddenly vanish from use due to legal arguments over its provenance.

Zlib and gzip, based on the known-and-already-trusted DEFLATE algorithm, were the answer to this dilemma, and given that Zlib compressed better and faster, as well as being legally unencumbered, meant that it quickly took over the role of compress.

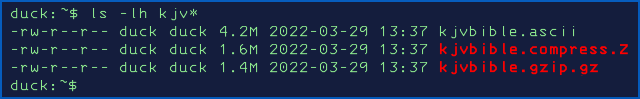

In ASCII format (about 100,000 lines, 800,000 words, 4.2MB); in compress format (1.6MB); and in gzip/zlib format (1.4MB)

Zlib still very widely used

Interestingly, numerous modern compression schemes provide significantly better compression, primarily by using lots more memory to keep track of repeated text (e.g. 7z for arbitrary data), or by equipping each end with a substantial dictionary of oft-repeated text strings (e.g. Brotli for compressing web pages).

But Zlib’s DEFLATE is nevertheless still the most likely compression scheme you’ll find, because it’s been so widely used for so long, and is therefore “built in” to numerous widespread file formats.

For example, Office documents such as DOCX and XLSX files are stored in ZIP format, using the DEFLATE algorithm to save space; so are Java JAR files and Android APK files; and PNG graphics files use Zlib compression internally.

Likewise, a huge number of web pages – probably the majority of pages you’ll visit – are compressed for transmission using Zlib, even though Google’s Brotli algorithm, which usually compresses better, is now widely supported by web servers and browsers alike.

What this means is that many apps you use regularly will include code not only to decompress Zlib data when reading it in, but also to compress to Zlib format when saving or sending data, because DEFLATE is a sort of lingua franca for compressed data.

And any of these apps – perhaps even most of them, if you’re on Linux or Unix – will use the Zlib implementation of DEFLATE, often in the form of a shared library (a DLL on Windows) called libz.so or LIBZ.DLL.

In a quick test on our Linux laptop, we found that the following apps all loaded the libz.so shared code into memory, ready for use if needed: the browsers Firefox, Edge, Chromium and Tor; the PDF reader Xpdf; the popular media player VLC; the Word-and-Excel compatible software LibreOffice; the image editor GIMP; and even our favourite HP desktop calculator emulator, Free42.

Surely no bugs left?

With a legacy that long, and with an algorithm that was locked down as an internet standard back in 1996, you’d no doubt assume that Zlib had very few bugs left, and that any serious ones, such as those leading to the sort of memory corruption that could be exploitable for remote code execution (RCE), would have been found by now.

After all, memory corruption errors, when triggered by mistake by randomly weird input, typically give themselves away by causing the app concerned to crash, which in turn typically leaves behind a telltale error trace saying which part of the program provoked the crashworthy behaviour.

And with all sorts of data getting compressed and decompressed all the time, often without you realising it (e.g. between a web server and your browser, where Zlib typically squashes and unsquashes the data invisibly for transfer)…

…you’d expect that even the most esoteric memory mismanagement bugs would be outed in the end, if only by chance.

Well, Google bug-hunter Tavis Ormandy, who has uncovered some truly funky bugs in his storied bug-hunting career, just found a curious and possibly, just possibly, exploitable bug in the Zlib code…

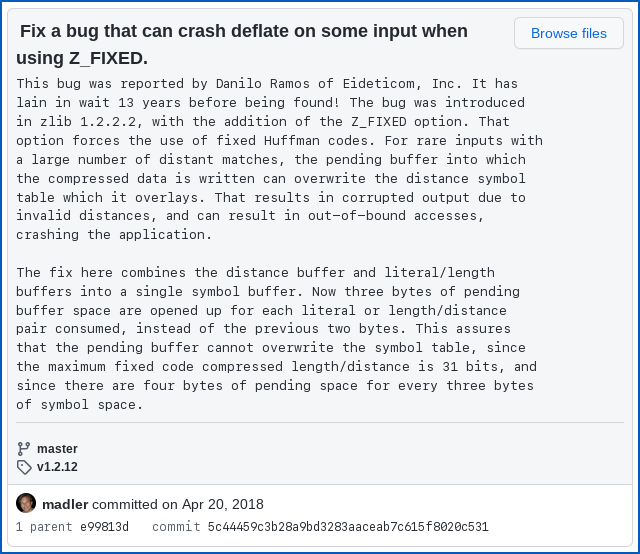

…only to discover, when he came to report it, that it had been reported and patched before, back in 2018, when it was wryly noted as being 13 years old:

This bug was reported by Danilo Ramos of Eideticom, Inc. It has lain in wait 13 years before being found! [2018-04-20]

Somehow, though, the patch committed back on 20 April 2018 never made it into an update to Zlib, for the simple reason that until 2022-03-27, the previous release of the library was published on 2017-01-15, more than five years ago.

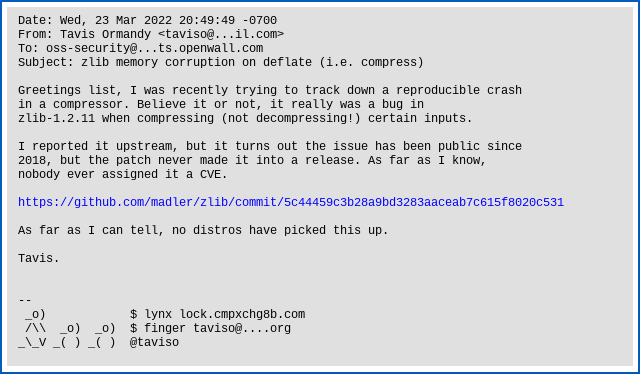

As Ormandy noted in his bug report:

Greetings list, I was recently trying to track down a reproducible crash in a compressor. Believe it or not, it really was a bug in zlib-1.2.11 when compressing (not decompressing!) certain inputs.

I reported it upstream, but it turns out the issue has been public since 2018, but the patch never made it into a release. As far as I know, nobody ever assigned it a CVE.

Ormandy’s surprise above is not just that the bug inadvertently went unfixed for all that time, but also that he’d discovered a potentially exploitable buffer overflow in the compression part of the code, rather than the decompressor.

Memory mismanagement can happen anywhere that a programmer is careless with which data gets written where, but in compression software it’s much more common to find this sort of bug in code that expands data from its compressed format, most notably because you can’t reliably determine how much memory space you’ll need to decompress everything safely until you actually try decompressing it.

(Many compression formats include a header that tells you how much space you’ll need to extract the data, but you can’t rely on that information because it could have been understated deliberately by an attacker to confuse your code and crash your decompressor on purpose.)

Astonishingly, if not actually amusingly, the fact that the bug was first investigated in 2018 means that the official bug number for this vulnerability is CVE-2018-25032, even though it was only assigned this week.

What to do?

- If you’re a user or a sysadmin, update to Zlib 1.2.12. Most Unix and Linux distros should provide this update for you. Although this bug is difficult to trigger, there are many places, notably on servers, where untrusted data that was supplied by an outsider gets compressed automatically and then archived, logged or transmitted by the system.

- If you’re a programmer, never assume that the “last bug” must have been found by now. Pay special attention to esoteric or unusual paths through your code that rarely get activated in real life – you may find bugs that time alone was not enough to expose by chance. If your code supports options that are not only rarely used but also not strictly needed, consider removing those parts altogether. You can’t trigger a bug in code that isn’t there.

- If you’re a product manager, never assume, just because a patch was produced, that it must have made it into the shipping code. Make sure that your software doesn’t have bugs that have been patched yet never actually fixed!

The price of freedom from bugs, as Mr Jefferson might have said, is eternal vigilance.

David C.

Great article, but you may want to mention that gzip is not really the format most people use for compressing files these days. It’s been a long time since I downloaded a file with a .gz extension.

These days, I see most content compressed with bzip2 and a smaller amount (especially from the GNU organization) compressed with xz. Bzip2 gets better compression ratios than gzip and xz compresses better than bzip2 – at a cost of performance – bzip2 is slower than gzip and xz is slower than bzip2 (much slower at high compression ratios).

Of course, it is not at all surprising that gzip is used for web content that compressed in-flight, because it’s the fastest of the three. It’s good and right to burn extra CPU time when you’re doing a one-time compression of a file for others to download. You probably don’t want to do that for arbitrary web content, since the goal there is to speed up the transaction.

Paul Ducklin

It’s not so much the files that you explicitly compress in a format of your choice that cause a preponderace of DEFLATE compression……

…it’s the files and content you produce and consume that *include data that gets DEFLATEd and later inflated, using a compression library that might well be Zlib*.

As for web compression, if you look at the the default “Accept-Encoding” settings of Firefox, Edge and Chromium you will see “deflate, gzip, br”. Loosely speaking, “deflate” here actually means Zlib (RFC 1950, which is the DEFLATE algorithm of RFC 1951 with a Zlib header); “gzip” means DEFLATE with a gzip header (RFC 1952) ; and “br” means Brotli, a dictionary-based compressor optimised for the web. Both “deflate” and “gzip” use the same underlying algorithm, as implemented in libz.so/LIBZ/.dLL. (Brotli is completly different.)

Neither “bzip” nor “xz” are official HTTP encoding standards, so the reason you rarely see them in web transers is almost certainly just that it’s easier and safer to stick to DEFLATE, which pretty much all clients and servers support, either sent in Zlib format (inaccurately but officially called “deflate” in HTTP) or gzip format (“gzip” in HTTP headers). The difference betewen z Zlib and a Gzip stream is just a hew header bytes at the start. Strip the header off altogether and you have a raw DEFLATE stream.

JimC_Security

Many thanks for this detailed article Paul.

I have raised a ticket with VLC for this updated zlib library to be added in the future: https://code.videolan.org/videolan/vlc/-/issues/26774

Separately the open source encryption tool Veracrypt was aware of this vulnerability and has added the updated library into a soon to be released version.

Paul Ducklin

The VLC team has understandably given this a moderate severity in their product because they only use it for decompression. (In my Linux distro, the included VLC app uses the distro’s libz, and my distro is up-to-date with Zlib so my VLC is implicitly updated, too. I suspect many Linux VLC builds will be the same. On Mac and Windows I suspect they compile it in, or ship their own “private” Zlib shared library.)

There doesn’t seem to be a way (well, not an easy way) to compile Zlib for decompression only, a reasonably common usage, given that many apps only need to consume compressed data, not to create it.

I presume they’ll update the Zlib code in some future release, but won’t do a release just to update Zlib.

JimC_Security

I have also since asked Malwarebytes and VMware (for their product Workstation Pro 16.2.3) to update the included version zlib.

Markus

Hi,

this question is probably for the zlib maintainer, but where do I get an updated zlib1.dll? I searched my Windows installations for zlib* and found several zlib1.dll files (some programs have more than one in their program directory). But I cannot find an official site to download an updated DLL.

The official site zlib.net only offers source code, no binaries (which is common with linux projects). It mentions two third party sites, which offer compiled binaries (http://www.winimage.com/zLibDll/ and http://gnuwin32.sourceforge.net/packages/zlib.htm) but both only have the outdated version 1.2.3 from 2005! The current version is 1.2.12 .

So, do I have to install a compile environment just to install this update?

Paul Ducklin

You might have to build your own… Visual Studio is an enormous thing to install (several gigs at the low end), and the licensing rules for the “free” version are somewhat confusing (especially if you work in IT or a company that itself builds code for any purpose), but that might do the job. Or you could try Clang for Windows. It’s still a massive install (more than a gig), but it’s free and open source (and no GPL, either), so the licensing is easy to comply with, whatever you do with the compiled DLL.

Markus

I had hoped, someone could point me to a newly release software package, with a current zlib1.dll in it. I shudder at the thought to use a complex build environment for the first time for something like this. I might set some setting and the resulting library doesn’t work on Tuesdays. Or it has some new security hole because I forgot to implement process X that “everyone knows about to do before the first compile”.