This post is somewhat of a side note but a really important side note and I’ll have more to add as Module 1 ends this winter. I’m posting it whilst working on a more comprehensive post for nahw.

In Arabic words are divided into two categories: ‘مُعْرَب’ (declinable) and ‘مَبْنِي’ (indeclinable). Now you’re thinking what does that mean? In simple terms this concept concerns whether a word can take changes to its case ending (declinable) or not (indeclinable). So what causes these changes? Well case-ending changes are caused by something called العَوامِل (governing elements). “Governing elements!?” I hear you say. It’s simple really. Words can change case-endings for two reasons: (1) because of the position they occupy within a sentence [subject, object…] and (2) because they are over-powered by the case of a governing particle. Examples are below:

(1) changes caused to a word because of its position in a sentence: Look at the following sentences: ‘the man read a book’, ‘I saw a man read the book’, ‘I read the book with the man’. Focus on the the phrase ‘the man’. In the first sentence ‘the man’ is the subject therefore: ar-rajulu الرَّجُلُ. In the second sentence ‘the man’ is the object therefore: ar-rajula الرَّجُلَ. In the last sentence ‘the man’ is majroor therefore ‘ar-rajuli‘ الرَّجُلِ.This is how words that are مُعْرَب change cases depending on their position within a sentence.

(2) changes caused to a word because of a governing particle: Let’s take for example prepositions. Imagine a muslim coming across a non-muslim. The muslim invites the non-muslim to become Muslim. If the non-Muslim agrees then he has to take the shahadah (declaration of faith) to become Muslim. He is also no longer called a non-Muslim, he is now called a Muslim. Now change ‘Muslim’ with harf-jarr حَرْف جَر and ‘non-Muslim’ with ism اِسْم. Imagine a حَرْف جَر coming across an اِسْم. The حَرْف جَر invites the اِسْم to become مَجْرُور. The اِسم takes a جَر case ending to become مَجْرُور. The اِسْم is now called اِسْم مَجْرُور. An example of this would be فِي + بَيْتٌ = فِي بَيْتٍ

These changes which have occurred are called الاِعْراب. Words can be fully declinable ‘مُنْصَرِف’ meaning that the word can take all case endings (e.g. ٌ ٍ ً ). They can also be partially declinable ‘غَيْرُ مُنْصَرِف’ meaning that the word cannot take all case endings (i.e. ُ َ َ ) for example, as mentioned in the previous post, words such as feminine names cannot take a kasra or tanween but can take a dhamma or fatha; and therefore it is declinable to an extent. So, words which accept changes by العَوامِل (governing elements) are called مُعْرَب and words which cannot change are called ‘مَبْنِي’. So what are the changes then?

The changes caused by العَوامِل are of 4 types (الحالات):

1) The nominative case – مَرْفُوْع

2) The accusative case – مَنْصُوب

3) The genitive case – مَجْرُور

4) The jussive case – مَجْزُوْم

Once you’ve identified a word’s correct case ending depending on its علمِل – what are the signs used to indicate this? It is through two ways. Think back to post week 2 where we formed that table with all the signs and cases and how case endings are indicated either through diacritics – الاِعْرابِّ الحَرَكات – or also through letters – الاِعْرابِّ الحُرٌوف.

However not all words accept these changes. These words are called مَبْنِي where, despite the العَوامِل the word retains its positions and diacritics and does not accept the concept of الاِعْراب. In this case the opposite of الاِعْراب occurs which is called البَناء. We mentioned at the beginning of this post that words can change for two reasons; because of its position within a sentence and because it comes after a governing particles which overrides its case ending. Let’s use those examples again using مَبْنِي words:

(1) changes caused to a word because of its position in a sentence: Focus on ‘this man’ within the following three sentences: This man read a book, I saw this man read the book, I read the book with this man. In each of these examples we used the demonstrative pronoun ‘this’-‘هذا‘- this word is مَبْنِب and although الرَّجُل takes a different ending in each example هذا remains the same. Note, however, that although it looks the same in each example intrinsically the case is still changing.

(2) changes caused to a word because of a governing particle: If we add a governing particle before a مَبْنِي word it does not change. فِي +هذا البَيْتٌ = فِي هذا اابَيْتِ

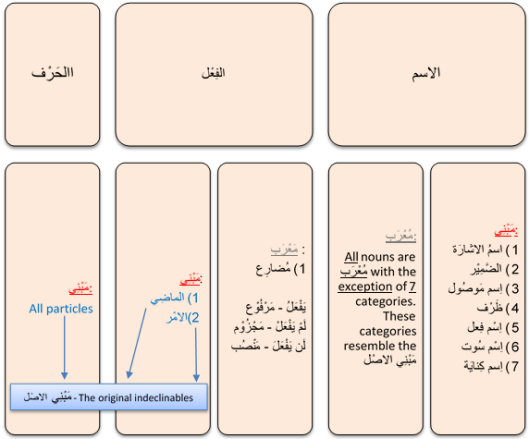

To sum up this information the following chart I put together may prove useful. It is an indepth breakdown of what type of nouns, verbs and particles are declinable or indeclinable. It basically shows that:

(1) all nouns are مُعْرَب with 7 exceptions – these exceptions are مَبْنِي only because they resemble characteristics of the مَبْنِي الاصل. For example, attached pronouns الضَّمِيْر are مَبْنِي because they consist of very few letters e.g. ها, ك much like particles (one of the مَبْنِي الاصل ).

(2) the مَبْنِي الاصل are the original indeclinables meaning that they were always مَبْنِي . There are 3 groups: all particles, the part tense verb (active and passive) and the command (including prohibition).

(3) This leaves us with the category of present/future tense verbs which are مُعْرَب. They are مُعْرَب because their case ending can change if a governing particular comes before it. The examples are listed in the box.

Each of the 7 indeclinable nouns will have a post dedicated to them under this page.That’s all for now and keep a look out for my next nahw post – it will attempt to summarise the fundementals.

Ma’salaam!

Arabic gem: العربية (Arabic) and المَعْرَب are inflected from اَعْرَبَ, يُعْرِبُ – اِبايَة which means to express!

Assalaamu ‘alaykum warahmatullah

Very helpful. May I ask when the 7 indeclinable nouns will be elaborated Or are they elsewhere on the blog?

LikeLike