The Muisca (also called Chibcha) are an indigenous people and culture of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia, that formed the Muisca Confederation before the Spanish conquest. The people spoke Muysccubun, a language of the Chibchan language family, also called Muysca and Mosca.[2] They were encountered by conquistadors dispatched by the Spanish Empire in 1537 at the time of the conquest. Subgroupings of the Muisca were mostly identified by their allegiances to three great rulers: the hoa, centered in Hunza, ruling a territory roughly covering modern southern and northeastern Boyacá and southern Santander; the psihipqua, centered in Muyquytá and encompassing most of modern Cundinamarca, the western Llanos; and the iraca, religious ruler of Suamox and modern northeastern Boyacá and southwestern Santander.

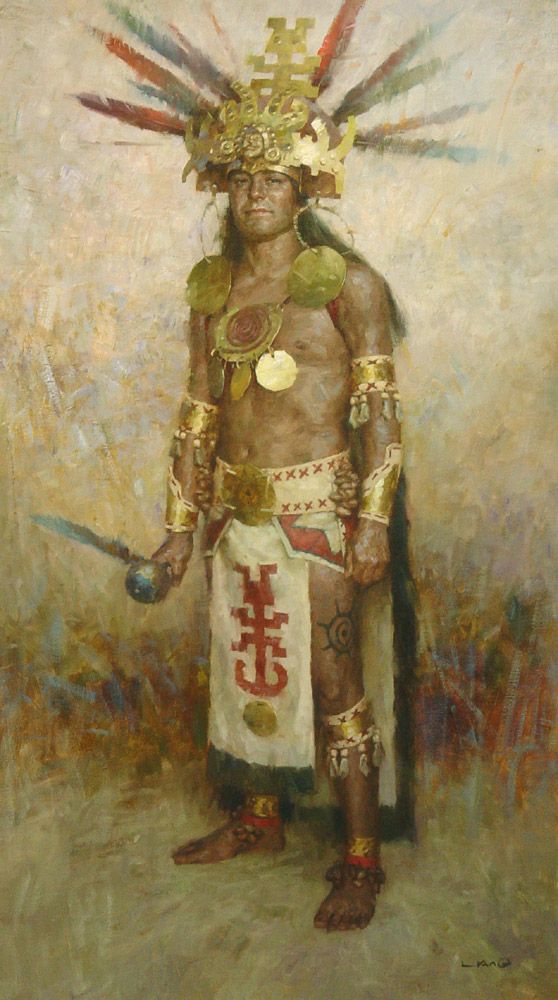

The Muisca (or Chibcha) civilization flourished in ancient Colombia between 600 and 1600 CE. Their territory encompassed what is now Bogotá and its environs and they have gained lasting fame as the origin of the El Dorado legend. The Muisca have also left a significant artistic legacy in their superb gold work, much of it unrivalled by any other Americas culture. The Muisca lived in scattered settlements spread across the valleys of the high Andean plains in the east of modern-day Colombia. Important annual ceremonies related to religion, agriculture, and the ruling elite helped unite these various communities. We know that such ceremonies involved large numbers of participants and included singing, incense burning, and music from trumpets, drums, rattles, bells, and ocarinas (bulbous ceramic flutes). The communities were also linked by trade and there was even a movement of skilled craftsmen, especially goldsmiths, between Muisca cities.

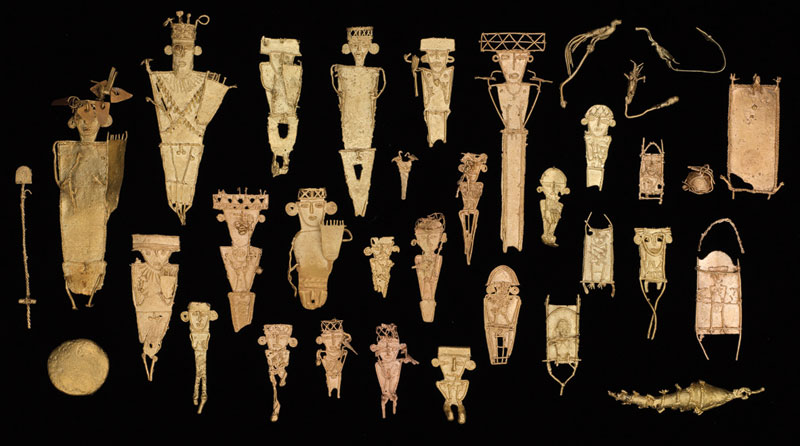

The Muisca (or Chibcha) civilization flourished in ancient Colombia between 600 and 1600 CE. Their territory encompassed what is now Bogotá and its environs and they have gained lasting fame as the origin of the El Dorado legend. The Muisca have also left a significant artistic legacy in their superb gold work, much of it unrivalled by any other Americas culture. Idolizing the sun, the Muisca also had a special reverence for sacred objects and places such as particular rocks, caves, rivers, and lakes. At these sites they would leave votive offerings (tunjos) as they were considered a portal to other worlds. The most important Muisca gods were Zue the sun god and Chie the moon goddess. We also know of Chibchacum, the patron of metalworkers and merchants. The most common type of offerings to the gods was foodstuffs along with typical tunjo of snakes and flat male, female, and animal figures rendered in gold alloy which were placed at sacred sites.

MUISCA MYTHOLOGY

The times before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca Confederation are filled with mythology. The first confirmed human rulers of the two capitals Hunza and Bacatá are said to have descended from mythical creatures. Apart from that other Muisca myths exist, such as the legendary El Dorado and the Monster of Lake Tota.

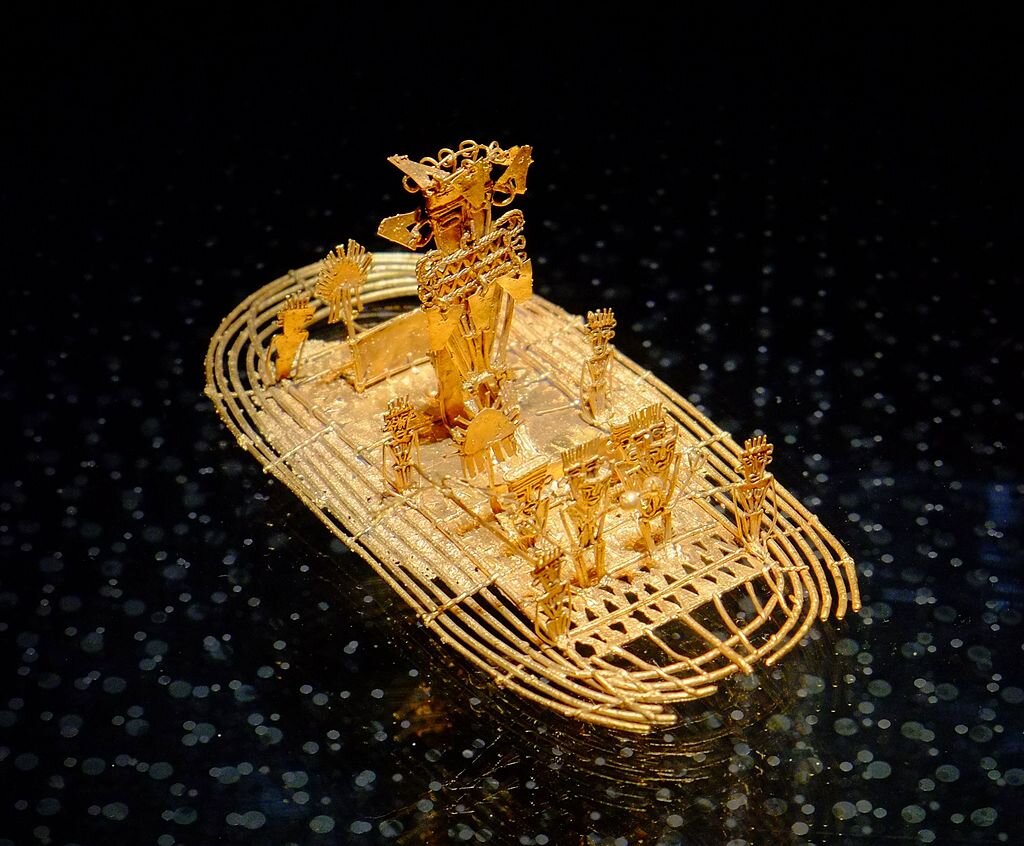

- El Dorado, the man or city made of gold, that was not so mythical but a main motive for the Spanish to conquer Colombia. The ritual is represented in the Muisca raft, a piece of gold working found in Pasca almost 400 years after the arrival of the Spanish

- Monster of Lake Tota, allegedly a monstrous snake or fish living in Lake Tota

- Hunzahúa Well, a well that according to the mythology of the Muisca originated from spilled chicha when the mother of Hunzahúa caught him and his older sister, Noncetá, while they were copulating.

- Fura and Tena, the first woman and man created by the god Are to populate the earth. Because Fura was not faithful, they lost their immortality, so they aged and died. Are took pity on them and turned them into rocky crags protected from storms, and Fura’s tears became into emeralds.

- Thomagata, said to have been one of the most religious of the zaques, after Idacansás

- Idacansás, allegedly a mythical priest from Sugamuxi who was able to change the order of things

- Goranchacha, a mythical cacique who moved the capital of the northern Muisca from Ramiriquí to the later capital Hunza

- Pacanchique, according to Muisca myths recovered his fiancé Azay from ruler Quemuenchatocha by first turning her into a dead person and then bringing her back to life using different plants. He also showed the Spanish conquistadores the way to Nemequene’s palace Other Muisca people where human and mythological character converge are:

- Hunzahúa, first zaque of Hunza, allegedly committing incest with his sister and said to have fled

- Meicuchuca, first zipa of Bacatá, one of his wives mythologically turned into a snake

The Muisca (or Chibcha) civilization flourished in ancient Colombia between 600 and 1600 CE. Their territory encompassed what is now Bogotá and its environs and they have gained lasting fame as the origin of the El Dorado legend. The Muisca have also left a significant artistic legacy in their superb gold work, much of it unrivalled by any other Americas culture. The Muisca lived in scattered settlements spread across the valleys of the high Andean plains in the east of modern-day Colombia. Important annual ceremonies related to religion, agriculture, and the ruling elite helped unite these various communities. We know that such ceremonies involved large numbers of participants and included singing, incense burning, and music from trumpets, drums, rattles, bells, and ocarinas (bulbous ceramic flutes). The communities were also linked by trade and there was even a movement of skilled craftsmen, especially goldsmiths, between Muisca cities.

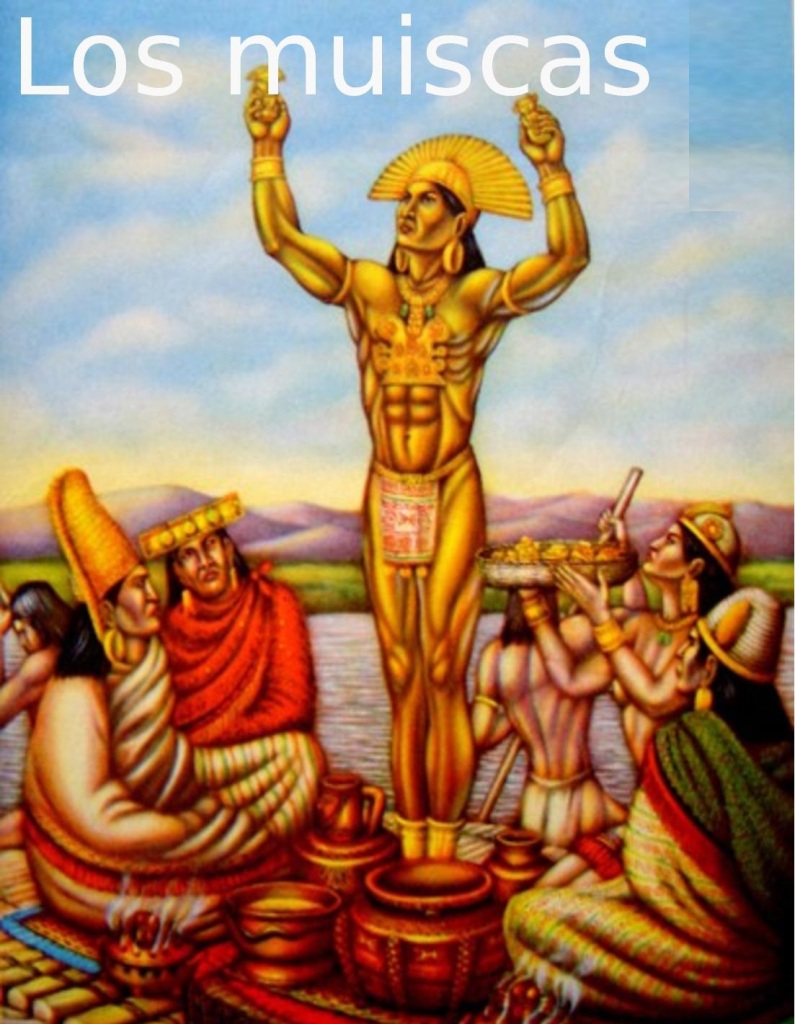

The Muisca people were flourishing in Colombia between 600 and 1600 C.E., but there is evidence of them in the region as far back as 1500 B.C.E. They were transitioning at that time from hunter-gatherers to farmers, like many tribes at that time. Their people were found from what is now the city of Bogotá, through the surrounding high mountains and valleys of the Andes. Their civilization was just as advanced and thriving as the more famous Inca, Aztec, and Mayan tribes, with a hierarchy in leadership, developed religious beliefs, and advanced farming, craft and trade practices. The Muisca spoke a variation of the Chibcha language, which historians believe originated in Central America, and so the Muisca are sometimes also known as the Chibcha people. Religious beliefs and practices were central to the life and community of the Muisca tribes. Sun worship was a fundamental component of their faith and can be attributed to their fascination and skill with gold. The origin of the El Dorado myth took root from the practice of the Muisca of covering their future chief with gold dust and floating him into the center of the lake on a gold raft where he would offer gold and emeralds to the gods, and be deemed the new leader. Several deities were central to the faith of the ancient Muisca, but the primary gods were Suéá, the sun god, and father of the Muisca, and Bachué, the water goddess and mother of the people. Since both sun and water are critical components of successful farming and survival, it’s only natural that these gods were revered and efforts would be made to appease them for a successful harvest.

The terms Muisca religion and mythology refer to the pre-Colombian beliefs of the Muisca indigenous people of the Cordillera Oriental highlands of the Andes in the vicinity of Bogotá, Colombia. The tradition includes a selection of received myths concerning the origin and organization of the universe. Their belief system may be described as a polytheistic religion containing a very strong element of spirituality based on an epistemology of mysticism. Bachué (“the Grandmother”) is a non-material principle of creation, the will, the thought and the imagination of all the things to come. She is a similar concept to the principle of tao in the Chinese mythology. The time of unquyquie nxie (“the first thought”) is the time of the cosmic origin, when the thoughts of Bague became actions. This is the time when Bague created the builders of the universe and ordered them to create.

- El Dorado, the man or city made of gold, that was not so mythical but a main motive for the Spanish to conquer Colombia. The ritual is represented in the Muisca raft, a piece of gold working found in Pasca almost 400 years after the arrival of the Spanish

- Monster of Lake Tota, allegedly a monstrous snake or fish living in Lake Tota

- Hunzahúa Well, a well that according to the mythology of the Muisca originated from spilled chicha when the mother of Hunzahúa caught him and his older sister, Noncetá, while they were copulating.

- Fura and Tena, the first woman and man created by the god Are to populate the earth. Because Fura was not faithful, they lost their immortality, so they aged and died. Are took pity on them and turned them into rocky crags protected from storms, and Fura’s tears became into emeralds.

The Muisca are the Chibcha-speaking people that formed the Muiscan Confederation of the central highlands of present-day Colombia’s Eastern Range. They were encountered by the Spanish Empire in 1537, at the time of the conquest. Subgroupings of the Muisca were mostly identified by their allegiances to three great rulers: the Zaque, centered in Chunza, ruling a territory roughly covering modern southern and northeastern Boyacá and southern Santander; the Zipa, centered in Bacatá, and encompassing most of modern Cundinamarca, the western Llanos and northeastern Tolima; and the Iraca, ruler of Suamox and modern northeastern Boyacá and southwestern Santander. Nemequene was the third Zipa of Bacatá, from 1490 to 1514. Nephew to Saguamanchica, ascended to the throne after his death. During his reign, he had to encounter many rebellions from different tribes inside and outside the Muisca Confederation. The main one was the rebellion of the Panches and Sutagaos, at Uzhaques. The zipa managed to confront them, and the king of the Sutagaos, Fusagasugá, left battle before it even end. Nemequene had to face many battles afterwards, and didn’t stop fighting until five days before his death. He’s considered the Legislator of the Muisca Confederation, as he created the Code of Nemequene, remembered orally by the people of the Confederation. Sentences were usually death penalty or repudiation and social exclusion. The acts of incest, sodomy, adultery, robbery, warriors’ cowardice and drunkenness were among the penalized crimes. In addition, the code established the rules of inheritance, behaviour, protocol, obedience, submission and tribute.