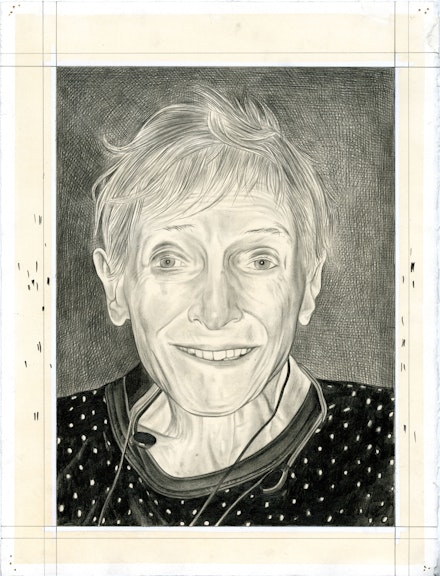

Art In Conversation

NANCY SPERO with Phong Bui

On the occasion of the artist’s traveling retrospective, Nancy Spero: Dissidances (which will be on view at the Museu d’ Art Contemporani de Barcelona until September 24, 2008, at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía from October 14, 2008 to January 5, 2009, and at the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo in Seville from January 27, 2008 to March 22, 2009), Nancy Spero (widow of painter Leon Golub) welcomed Rail Publisher, Phong Bui, last week to her home/studio in La Guardia Place where she has lived since 1972, to talk about her life and work. The conversation began on a rather late side of the evening, when many who are familiar with Spero’s unconventional sense of time and space know that this is the only time anyone can see her. And before Meena Gonzales’s arrival with her brilliant home-cooked meals, there had always been ordered-in dinner with paper plates, plastic forks readily at hand, partly because Spero would prefer not to lose time over food’s preparation.

Phong Bui (Brooklyn Rail): The German writer Max Friedlander once said, “It’s easier to change your worldview than the way you hold your spoon.” In your personal reflection, “Creation and Procreation” [1992], you confessed that while raising your three sons and allowing Leon to fulfill his potential as an artist, you had to assert yourself to maintain your own practice, and by doing so, had to work only at night. Therefore, you never had enough sleep, which in turn has become a habit that you can’t seem to break. Would you, thinking back to the time you were in Paris from 1959 to 1964, comment a bit on this persistence, and whether or not it shaped your mature work? Otherwise, do tell us of your early training as an art student.

Nancy Spero: It’s absolutely true in terms of perseverance. That was my only option. But you’re right, it did become a habit, which I am still trying to break, as my doctor has been telling me to do in the last few decades. But as far as going back to my youth, I do remember making all kinds of drawings on the margins of my books in high school. Then, later, when I went to college at the University of Colorado, Boulder for just one year, I had this funny notion that art was not contributing to society. So instead I took chemistry, which made me miserable. Finally I had to give in because I thought that art was the only thing I was really interested in; it was the only thing with which I can express myself most naturally and fully.

Rail: That was when you came to Chicago to enroll at the Art Institute in 1949, when you met Leon (Golub) a year later after his return from the army in Europe?

Spero: Yeah. First of all, it was just great to get out of my parent’s home in the suburbs north of Chicago, which was so full of wasps and there were no Jews on site.

Rail: That’s quite ironic since the suburb was invented by a Jew, Abraham Levitt, and his two sons, William and Alfred, in 1947.

Spero: How strange! Anyway, it was, secondly, so brilliant to be at the Institute in those years because then the school was part of the museum itself. As you can imagine, the feeling I had as a young art student—the whole museum was all mine. Meeting Leon in the third week of class made a great impression on me. I was taken by his political conviction, and we were married a year later. Then between 1957 and 1959 we lived in Italy and Bloomington, Indiana with our two sons, Stephen and Philip. Right after that, we moved to Paris and lived there for a good five years. Our third son Paul, in fact, was born in Paris.

Rail: It must have been quite intense the year you came to Paris, in 1959, because it was the year that the French army, especially during Operation Jumelles Colonel Bigeard, proclaimed that the French were fighting for the Algerian Revolution, defending their freedom as if they were defending the West’s freedom, which led to de Gaulle’s dramatic change of mind by refusing to recognize the gpra [Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic]. It was also the same year in my country, Vietnam, that the National Liberation Front was created, as was Ho Chi Minh Trail, the beginning of large scale operations against Diem’s unpopular South Vietnamese military. You and Leon must have been affected by all of those political events.

Spero: For sure. The Gaullist regime showed no signs of bringing the anti-colonial struggle to an end. They certainly didn’t learn much from their defeat at Dien Bien Phu [1954]. Obviously, things built up by 1960. The anti-war movement was led by students and leftist intellectuals, including [Jean-Paul] Sartre, [Simone] de Beauvoir, [Pierre] Boulez, and many others. Even the liberal intelligentsia sided with the Algerian independence struggle. However, the big blow came in December 1960, when French troops joined with other European-derived populations in Algeria and began their murderous attacks on the crowds during their mass demonstrations under the fln [National Liberation Front] banner. The political crisis didn’t get any better when we moved back to New York in 1964: the war in Vietnam was getting worse, tension escalated. I remember looking down the street with Paul in my arms on a Sunday afternoon, and there was a group of young people marching against the U.S. government for having entered the war against Cambodia. Actually, the next day many of us artists lounged on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum and somebody had forgotten the horn. Meanwhile, they saw Leon, who had a robust voice, and asked him to come up to the steps to announce that we were trying to close down the museum that afternoon in protest against the U.S. government for its political action. It was funny because my voice was just as big as Leon’s in those days. And I used to be so tense when we’d go in a restaurant because there was Leon, and when he got interested in a subject of his liking, God, I would get just all uptight because he would start talking to mostly whoever was there, and his voice would just be getting louder and louder. I remember people kind of cringed at us [Laughs].

Rail: [Laughs] That certainly had its natural continuity that fed right into the founding mission of a.i.r. Gallery in 1972?

Spero: I never thought of it that way, but we sure were a bunch of feisty girls who wouldn’t be taken so lightly. We really thought that we all could change the world into a better place, especially for us women artists. If we didn’t do it, who would, really?

Rail: I couldn’t agree with you more, because the calling for action was ripened by time and place in that particular chapter of history. At any rate, I’m curious about the vertical painting “Hangman” [1958] painted while you were in Indiana. As you had often said, you were thinking not of subject matter but of the format of Tarot Cards. Though, in my reading I felt that it already seemed to signal your early attraction toward both space and images of great ambiguity, which then transformed and carried through the horizontal format of the “Lovers” series. And as elegiac and somber as those paintings were, which we’d spoken about in the past, they have pictorial similarities to what Susan Rothenberg was doing in the late ’70s, in terms of how the images would suspend in a kind of frenetic atmosphere where the composition only serves as a secondary role….

Spero: She in fact owns one of the “Lovers” paintings.

Rail: Hmm…and their images persist on a couple who was trying to separate.

Spero: And at the same time, despite the fact they’re glued to each other, they’re very lonely figures. The whole sentiment was about existential feelings I had due to all the anxieties building up from the Algerian and Vietnam War and being in Paris. That’s the reason why you can’t identify them as male or female. I was, at the time, so obsessed with this possible opening of a kind of plethora, that would reveal my internal feelings as well as what was going on in the world externally. What can one do as an artist when you see all the violence being carried out in the world? I was never interested in making clear illustrations of all of those hideous events.

Rail: That’s why Sartre, in his writing of Jean Genet’s second metamorphosis, spoke of Evil as “Beauty glimpsed by Hatred”; the beauty of the aesthete is Evil as power of order.

Spero: Isn’t that frightening? As much as one tries to sort things out through paintings, it’s just impossible to decipher the real meaning of it. Those paintings were full of contradictions and disjunctions, as much as they were about continuity and discontinuity. I’m closing my eyes now and I see a very ugly image.

Rail: Yeah. But Baudelaire once said, “If you don’t know how to be ugly, you’re not beautiful.”

Spero: I couldn’t agree more with Baudelaire.

Rail: How about “Homage to New York (I Do Not Challenge)”, which…

Spero: I painted that while I was in the midst of painting “The Lovers.”

Rail: It also has, again, this strange double image of two heads with rabbit-ears and tongues sticking out. In the middle, there was a phallic-like tombstone. Would you consider that the first painting in which you had incorporated text as part of the visual field?

Spero: I’d done all kinds of scribbling with writing in my lithography class while I was in college. But you may be right, “Homage to New York” may be the first piece that I painted with oil. Again, the tongue is both about being thirsty and longing to get back to New York as much as about mocking the male-dominated artists of the first and second Abstract Expressionist school.

Rail: Yikes! You really thrive on your contradiction…

Spero: [Laughter] I suppose I do.

Rail: Could you talk about the “Fuck You” painting?

Spero: That was right in the midst of all of this too. One night I just stopped painting in oil. I went over to the table—this was in Paris—and I took out a sketch book with good water color paper and began to paint with gouache and ink. My God, I really tried to be a proper woman but I couldn’t [Laughs]. The truth was at first I was feeling existential, then I just simply became angry.

Rail: All of the contradictions, feeling angry, marginalized, misunderstood, it makes good sense that you would be attracted to Artaud’s work. When did you discover his writings?

Spero: I was initially introduced to Artaud’s writings through Jack Hirschman.

Rail: Who did that great anthology of Artaud for “City Lights,” 1962?

Spero: Yeah. Leon and I met Jack through Clayton Eschleman in 1957 when we were at Indiana University in Bloomington (this was long before he founded Caterpillar Magazine). Consequently, when we were in Paris, I became even more identified with Artaud. For me, the spoken words were part of the body, as if whatever I was trying to paint, and my own awareness of pain and anger—you can call it the destruction of the self—was an integral part, that duality. Things get split up right in the middle, which I was very much interested in at that moment in my life.

Rail: That’s the reason why in Theatre of Cruelty Artaud talked about it as a kind of recovering process of an emotional state of mind, being as a unique language caught half-way between gesture and thought...

Spero: Exactly. I could also certainly relate to his mental and physical pain partly because I was suffering a great deal from my early development of what turned into a severe arthritis, which hasn’t gotten any better ever since.

Rail: I’m thinking of the pronounced image of the profiled head screaming, which becomes the sight of the large tongue. In addition to its various phallic implications, while substituting for the verbal form that speaks of and for the body, and as different as your own depiction of pain and Picasso’s are; have you ever thought of Picasso’s “Weeping Woman” paintings, where her mouth is exposed as a deep cavity, the eyes are twisted, pricked by the arrow like eyelids that turn inward? I mean the whole construction of the head resembles what Rimbaud called “derangement of the sense.”

Spero: Picasso certainly had some anger issues [Laughs]. But his were usually directed against women he’d been with. Don’t you think so?

Rail: Definitely. That whole series had to do partly with what came out of “Guernica” in 1937, and his eventual break up with Dora Maar that followed.

Spero: Regardless, his was from a male’s perspective, opposite from mine; Picasso was inescapable for any artist. However, I did look at his work, especially while I was in Bloomington. Not so much while I was in Paris. Leon, on the other hand, was more involved with Picasso, ever since he saw “Guernica” at the age of fifteen when it was shown at the Chicago Art Club in 1937.

Rail: I’d like to shift briefly to the change of medium. At some point in the mid ’60s, you gave up oil painting and began to paint on paper. I’m interested in this in the context of how works on paper would only become legitimized as a work of art in the early ’80s. Since then there have been artists who solely make works on paper, such as Mark Lombardi, Dawn Clements, Simon Frost, and many others, including my recent discovery of the Swiss artist Sylvia Bachli. But you, starting with the “War Paintings” in the mid ’60s, had worked on paper and expanded it into a much more complex and transformative medium. Would you comment on whether you were conscious of the potential of the medium and the material from the outset?

Spero: I always had to fulfill certain needs—that involves changes at certain times in my art. I always knew that I didn’t want to pound anything to death, because it would just bore me to tears. And so that’s what happened there, even though they were painted on good paper. What I really wanted was to make them all look cheap in a sense. And because I was careless in a lot of ways, it ended up looking even more unfinished than I intended. I was really unconscious about the process, just letting the images breed on their own. One jumped into another in a form of metamorphosis, like “Sperm Bomb” looking like a male’s testicle, or a helicopter that has multiple breasts hanging down below with people sucking on them, etc… They’re not at all meant to be edited, they just came right out and I painted them very quickly. Maybe it had something to do with my secret rebellion, which nobody knew about. Leon knew about it but I didn’t bother him too much because he too was busy doing his work.

Rail: What interests me the most about the “War Paintings” series is that they are modest in scale, but emotionally quite demanding. This is a matter of scale; later, however large some of your site-specific installations were, they’re in fact quite intimate. Is that a fair reading of your work?

Spero: Not that I never thought about scale, which we all know is a matter of visceral feeling of space rather than an intellectual reading of it. But now that we’re talking about it, being vulnerable and sensitive to what was happening in the world may have something to do with my own observation, which then became a conduit to what was going on in the studio. That whole body of work was, in a way, my personal manifesto, made in a hurry, against the war in Vietnam. I was feeling upset as an artist who had no voice, and at the same time, I was thinking of the horrible symbiotic relationship between the oppressor and the victim. Besides, being vulnerable is not the same as trying to make clear moral distinctions, and so on.

Rail: This is an inner belief that you shared so deeply with Leon. The only difference is that you use the images of women to represent male violence. I thought it was quite fitting that in 1996, the fiftieth anniversary of the first atomic bombing of Hiroshima, both you and Leon were given the Third Hiroshima Art Prize.

Spero: That was quite an honor. It was terrific that they were aware of both of our work.

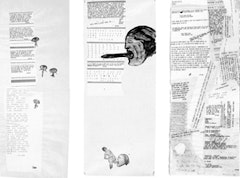

Rail: Nancy, when you made “Codex Artaud,” it was considered your first attempt at utilizing multiple sheets of paper with collage elements of typed texts and figures, which I saw for the first time at the New Museum Retrospective in 1989. Not only with its format, being scroll-like and filmic in appearance while evoking Chinese painting, illuminated manuscripts, Egyptian art, fragments of old newspaper, and so on; but their groupings opened up for various spatial possibilities in terms of how they are seen on and off the grid. Even though it is structured irregularly, I wonder whether the serial, repetitive tendencies that were so pervasive in minimal art by the early ’70s had somehow overlapped your visual thinking?

Spero: Well, minimalism was in the air, as they say. It had to do with what I was doing, and up to a certain point, the work wanted to change, so I just went along with it like I always do. Just like what happened after “Codex Artaud,” I realized that his pain was an internal state, so I felt like I was compelled to deal with real pain and torture in the real world, especially to women. Don’t forget the other difference was that, unlike the minimalists’ exclusion of the hand, I insist on every touch of the hand.

Rail: Did that change occur partly because of your involvement with awc [Artist Workers Coalition], war [Women Artists Revolution], and Ad Hoc Committee of Women Artists? And within the same year, you co-founded A.I.R., the first women’s gallery in nyc. You certainly were busy.

Spero:I sure was [Laughs]. And that was true about leaving Artaud and France behind in order to focus on women’s issues.

Rail: So, quite contrary to “Codex Artaud” is “Hour of the Night I” [1974] and “II” [2001], with nearly thirty years in between. While the former emanates a sense of lightness only to prop it up against the weightiness of content, mostly revealed in texts, spelling out words such as “body counts”, “torture in Vietnam”, “shoot out”, etc… what it seems to express, perhaps, is your anguish at what was going on with the 60,000 American casualties, and two hundred billion dollars in military expenditures (pointed out in one of Susan Harris’s essays). The latter is densely colored, constructed with more layers of various images and patterns. (With the exception of two repeated images of a woman being tied to a chair). Otherwise it seems to include many goddesses from many cultures. As a whole, there is an incredible celebratory feeling of lightness and musicality. However, don’t you think that the latter piece would not come into being without all the site-specific installations you have done in between?

Spero: Well, I think it began in the late ’80s when I felt the work needed to be opened up to the expanded field. Having turned from paper scrolls that wrapped around the gallery walls to address the architecture itself, which I did at Anthony Reynolds Gallery in London in 1990, I realized that the imagery, whether figures or texts, were leaping off of their constraint format of the paper, to be dispersed like a dance, only, however, to accommodate the given space.

Rail: You mean the few versions of “Ballad of Marie Sanders” first at Smith College Museum [1990], at the Jewish Museum [1993], and then at Festspielhaus Hellerau in Dresden [1998], particularly the installation of “Minerva, Sky Goddess, Madrid” [1991] where you printed images in all scales and sizes directly on the terrace, floor, and walls of the Circulo de Bellas Artes?

Spero:Yes. Since you mentioned the work being musical, and in reference to my desire to address my work to a wider audience, in other words, bringing the work out of the studio practice, it would be the same with shifting from chamber music for full-tilt symphony. That was when I was so involved with the astringency, reiteration of Pompeian frescoes, Egyptian art, illuminated manuscripts, Sumerian wall painting, Asian scroll painting, and so on. I wanted the figures themselves to become a form of protagonist dancing through various time and space. God, there are so many millennia which can serve as the bases for art making. It’s endless if you want it to be.

Rail: Since you were invested in Artaud, who in his reconfigured use of language, wanted both the actors and audience to be part of the whole theatrical experience, the same can be said of your site-specific installation, which also encourages the viewer to participate more actively—I wonder whether your apprenticeship in scene design at the Ivoryton Summer Theater in Connecticut in 1950 had perhaps given you a first glimpse into the spatial proscenium with theatrical backdrops and scene designs?

Spero:How much your experience in the past recurs or has direct links to what you’re doing in the present is always hard to say. But in some ways it stays, get digested, and becomes part of your visual language. That summer, even though I didn’t do much, I observed and took mental notes—that was my first-hand experience of theater, really. Yet I always knew that I’d never be involved in theater.

Rail: One can say that you’ve created your own theater in visual equivalence.

Spero:I’m glad you see it that way.

Rail: As the law of contrast that seems to persist as a perpetual basis of your work, I thought once again of the lightness of “Dreamtime Figures and Mourning Women,” installed at the CGAC [Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea] in 2004, as opposed to the heaviness of “Cri de Coeur” at Galerie Lelong a year later. The only thing they both share was their installment right along the bottom of the gallery’s walls. Do you think, in addition to the repetitive mourning gestures of the standing figure in profile, particularly in “Cri de Coeur,” they were your own way of paying homage to Leon?

Spero: Roberta Smith, you, and a few others felt that way about it; I didn’t then. But it’s starting to sink in right now [Laughs].

Rail: Could you tell us the genesis of how “Kill Commis/Maypole,” a work on paper in 1967, became a three-dimensional installation, made particularly for last year, at the 52nd Venice Biennial?

Spero:When Rob Storr came in his last visit and proposed the front space of one of the pavilions, which was more elevated because of the high ceilings, I thought immediately of “Maypole” being a three-dimensional installation. Similar to the way some have realized how relevant Leon’s works were, especially right after the Abu Ghraib episode, I wanted to make a point that there hasn’t been that much of a change from what happened in Vietnam and what we’re going through right now in Iraq.

Rail: You know, I once spoke to Leon about why it is hard to make political art. He said that’s like asking, “Why is it hard to make good art?” After an hour of discussing over these differences, we both came to conclusion, which was that to be political meant many different things. Is it political in a psychological or philosophical sense? Or is it artistically political? Or just simply politically political? What actually made Leon’s work so prescient is that it was politically political, and painting happens to be his chosen vehicle. Do you think of yourself and your work in the same light?

Spero:Yes, I do. Although Leon’s was consistently on the heavy side. He always poured it down like a lightning bolt. His was about obsession and investigative while mine can be distractible, at times light, other times serious. it sort of goes back and forth on my political interest and other concerns. I am not as singular as Leon was. Though I must say that having been married to him for…. Fifty-three years, I must admit that my life wouldn’t have turned out as the way it has.

Rail: Would you think that now with the desire of being heard, understood, and all the struggle in the last four decades, which have brought a certain confidence among younger women artists; in that they are more comfortable with their ambitions, especially in the public realm without the male’s notion of hermeticism?

Spero:I’d hope so. Why be passive and conventional? The fact of being an artist has already removed you from being normal. And then the question is: why even try? It’s difficult either way.

Rail: Having been able to keep up the demand of your work, making the necessary adjustments for personal growth as an artist, are there any other wonderful surprises that have happened in your life?

Spero:Yeah, I never thought I would get married and have children. I just kind of walked into it. You know I used to write to my darling sister Carol that I was taken by Leon because of his silver tongue. He always had many interesting things to say [Laughs].

Rail: So does your son, Philip.

Spero:That’s true. Between the two of them, they would have these discussions. Oh my god...

Rail: I can only imagine. Actually, all of your three sons are so distinctly different from one another. The matured, responsible professor in Stephen, the radical anarchist writer in Philip, and the romantic playwright in Paul.

Spero:You know, being with Leon and having my three beautiful sons, I am really blessed in a lot of ways. Otherwise, by living day-to-day, one realizes the firmness of cruelty, what people do to each other. But then one realizes that it’s always built with double meaning of the conflicted self. Whether it’s through language and gesture and thoughts, and so on…

Rail: That’s true. And that’s why we deal with that intense closeness of that duality through art, instead of hurting ourselves or others which I think is overrated.

Spero: I totally agree.