You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

❙❋❙✄❍❇◆❋❙*<br />

❚❏❖❉▼❇❏❙•❉◆◆❊❙❋•❚❋❍❇•❖❏❖❋❖❊•❇❇❙❏•❇❉❙❖•✠✄◆❙❋<br />

❙❋❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* ❏❚❚❋✄❖❋<br />

£5.99 UK • $13.95 Aus • $27.70 NZ<br />

I S S U E O N E<br />

❚❏❖❉▼❇❏❙✄❚◗❋❉❏❇▼<br />

●❙◆✄❍▼❙❏❚✄◗❇❚✄✄◗❙❋❚❋❖<br />

◆❇❚❋❙❙❖❏❉<br />

001<br />

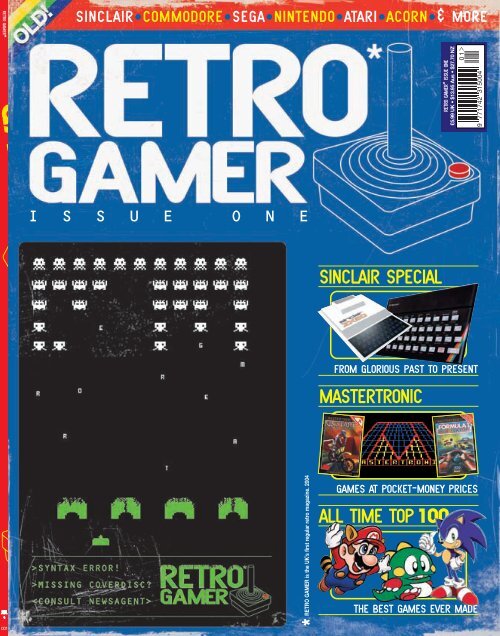

GAMER is the UK’s first regular retro magazine. 2004<br />

*<br />

RETRO<br />

❍❇◆❋❚✄❇✄◗❉▲❋✏◆❖❋✄◗❙❏❉❋❚<br />

❇▼▼✄❏◆❋✄◗100<br />

■❋✄❈❋❚✄❍❇◆❋❚✄❋❋❙✄◆❇❊❋

insides 01<br />

| ❙❋❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | |<br />

06<br />

<strong>Retro</strong> News<br />

66<br />

Horror Movie Licences<br />

73<br />

1983 Advertising Gallery<br />

08<br />

Sinclair Researched<br />

John Southern fawns over<br />

Sir Clive Sinclair’s range of<br />

classic micros<br />

30<br />

The Top 100 <strong>Retro</strong> Games!<br />

10 games on 10 formats. Do<br />

you agree with our choices?<br />

**4**<br />

52<br />

Mastertronic, a History<br />

Anthony Guter looks at the<br />

history of the classic budget<br />

software publisher

18<br />

Return of the Rings<br />

A fascinating look at the<br />

many games based on<br />

Tolkien’s epic novel<br />

24<br />

Hall of the Miner King<br />

Martyn Carroll walks down<br />

Surbiton Way in search of<br />

Miner Willy<br />

84<br />

Emulation Nation<br />

92<br />

Coverdisc<br />

98<br />

Next Month<br />

60<br />

Street Fighting Clan<br />

Charles Brigden takes an<br />

swipe at the long-running<br />

Street Fighter series<br />

**5**

| ❙❋❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | news |<br />

The latest news from the<br />

world of retro gaming<br />

Get Your Rocks<br />

Off<br />

Nope, it’s not a long overdue reworking of Asteroids sadly, but the almost<br />

comparably exciting news that grubby little seed-meister Leisure Suit Larry is pulling<br />

on his raincoat once more and sinking into the murky underworld of sex shops,<br />

brothels and ladies of the night for another close-to-the-bone adventure!<br />

This seventh Larry adventure, dubbed Magna<br />

Cum Laude, (which is actually some sort of Yankee<br />

award for being the biggest swot in a particular<br />

university, but also has the word cum in it, making it<br />

naturally ‘hilarious’ LSL fare), introduces Larry to the<br />

younger, hipper<br />

scene of PS2 and<br />

The lewdster returns in a brand new<br />

Xbox, and also<br />

adventure, the seventh to date<br />

reacquaints him<br />

with his old friend<br />

and sleazing<br />

buddy, the PC.<br />

Taking its<br />

inspiration from such high-brow art house films as<br />

American Pie, we can expect lots of leching and<br />

leering, but not a whole lot of actual lovin’, as<br />

Larry gets knocked back time and again by the<br />

lovely ladies in the game. While no one on the<br />

<strong>Retro</strong> Gamer team can imagine what that must feel<br />

like, we’re looking forward to finding out. So, get<br />

your leisure suits dry-cleaned, pressed and ready<br />

<strong>Retro</strong><br />

for action when this one arrives later<br />

Zone<br />

this year!<br />

The second Micro Mart Computer Fair took place at the NEC in November, and<br />

once again the star of the show was the <strong>Retro</strong> Zone. Like an island of tranquillity<br />

in a hall full of sweaty bargain hunters, the <strong>Retro</strong> Zone gathered together the<br />

cream of the current retro scene. Allan Bairstow from Commodore Scene magazine<br />

was in attendance, showing off both classic and contemporary Commodore<br />

machines. Ever seen an accelerated C64 with a 4Gb hard drive? You would have if<br />

you were there. Other attendees included representatives from QUANTA, showing<br />

several generations of the Sinclair QL, Colin Piggot from Quazar (issue six of his Sam<br />

Revival magazine is on sale now) and Colin Woodcock, editor of the ZXF online<br />

Spectrum magazine. As an added treat, Arcade Warehouse supplied several arcade<br />

machines for the day, including the classic Dragon’s Lair.<br />

The <strong>Retro</strong> Zone event was expertly organised by Micro Mart column writer Shaun<br />

Photographs from the recent<br />

<strong>Retro</strong> Zone event<br />

Bebbington, who<br />

also showed off rare computers from his<br />

extensive collection. Overall, the fair was a<br />

success, and the <strong>Retro</strong> Zone a highpoint. Here’s hope that it goes ahead again next<br />

year, and if it does, don’t miss it!<br />

**6**

Buried Treasure<br />

If you’re too thick to figure out the emulation stuff (or just irritatingly honest), then<br />

don’t worry, you don’t have to miss out on your retro fix. Companies like Midway<br />

are realising that “there’s gold in them thar cupboards”, so they’re busy dusting off<br />

their back catalogues and repacking them as anthologies of loveliness. The latest<br />

is Midway Arcade Treasures for the PS2, Xbox and GameCube.<br />

Featuring 22 classic titles, MAT is a trip down memory lane that will moisten<br />

the eyes of anyone who’s got a lifetime of gaming experience behind them. Here’s<br />

a list of what’s on it (deep breath) – Spyhunter, Defender, Gauntlet, Joust,<br />

Paperboy, Rampage, Marble Madness, Robotron 2084, Smash TV, Joust 2,<br />

Bubbles, Roadblasters, Stargate, Moon Patrol, Blaster, Rampart, Sinistar, Super<br />

Sprint, 720, Toobin’, KLAX, SPLAT!, Satan’s<br />

Hollow and Vindicators!<br />

Now if there’s nothing in there to get you<br />

drooling you must have sold your soul to EA.<br />

And believe us, you’re going to hell for that.<br />

Codemasters<br />

Honored<br />

Founders of Codemasters, Richard, David and father Jim Darling, have all been<br />

honoured recently by the UK computer and videogames industry. At the industries<br />

annual dinner the father and sons, who formed the company in 1986, were<br />

presented with the ELSPA Hall of Fame award.<br />

Richard and David were teenagers when they launched Codemasters with father<br />

Jim acting as Chairman. The brothers had already been creating games for some<br />

years, firstly selling via mail order before working as developers for publishing<br />

companies, which provided the funds to form Codemasters in 1986. Since their first<br />

release ‘BMX Simulator’, Codemasters<br />

has had over 60 number one bestsellers<br />

and published some of the<br />

games industries most popular titles.<br />

David Darling, CEO of Codemasters said<br />

“We’re honoured to receive the award.<br />

We’ve always been passionate about<br />

creating games and to be recognised by<br />

ELSPA is immensely pleasing”.<br />

Play these classic Midway games on<br />

your next-gen console<br />

Fashion<br />

victims<br />

Half<br />

Fish.<br />

Half<br />

Machine.<br />

All Cop<br />

Thirteen years after he first made his debut,<br />

James Pond has returned. Originally<br />

appearing on the Amiga ST and then<br />

gracing the likes of Sega’s Megadrive, the<br />

chubby-faced mecha-fish finally slinks his<br />

way onto the PSone, a machine that in<br />

itself could be deemed as retro.<br />

Robocod was the second outing for<br />

James Pond, who proved to be one of the<br />

most memorable platform characters of the<br />

16-bit era. Purists will be pleased to note<br />

that the game is exactly the same as the<br />

1992 Atari ST version, apart from a slight<br />

reworking of the intro sequence. Dr Mebbe<br />

has hijacked Santa’s Lapland toy factory and<br />

kidnapped all the little elves. What a<br />

horrible little sod! Fortunately our hero<br />

Robocod, with his magically expanding<br />

stomach (it goes up instead of the one<br />

you’ve got, that goes out), is on the case,<br />

sure to bring scaly justice and free the<br />

dynamite-bound elves. What follows is 36<br />

levels of platform mayhem for the<br />

bargain price of £9.99. All we wonder<br />

know is what happened to the PS2<br />

update of Robocod, originally<br />

announced a couple of years ago?<br />

Robocod has been released by budget<br />

specialists Play It, and is out now.<br />

We’ve come a long way (baby). Games are in fashion –<br />

literally. No longer the preserve of the spotty kid with a<br />

pasty pallor even Steve Davis would snigger at,<br />

suddenly the world is realising what we’ve always<br />

known – games are cool! And now you can wear your<br />

obsession with pride. Fashion labels are springing up all<br />

over the place, each desperate to cash in on the craze,<br />

but in our opinion none are doing it with more style than<br />

the Joystick Junkies (www.joystickjunkies.com).<br />

With a whole range of eye-catching t-shirts (and yes,<br />

hotpants!) that you really wouldn’t be ashamed to be<br />

seen wearing down your local roller disco, there’s<br />

something for everyone – from Space Invaders to<br />

Defender and all the way up to perhaps the greatest<br />

video game ever, the mighty Sensible Soccer. And all at<br />

more than reasonable prices. So get along to their Web<br />

site for a look and smarten yourself up!<br />

**7**

| ❙❋❯❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | sinclair researched |<br />

**8**

Sinclair<br />

Researched.<br />

We simply couldn't<br />

launch a retro magazine<br />

without running a<br />

feature on the Sinclair<br />

range of computers.<br />

John Southern, our<br />

resident Sinclair<br />

expert, looks at every<br />

model, from the ZX80 to<br />

the QL, and brings us<br />

up to date with what's<br />

happening in the<br />

Sinclair scene right<br />

now<br />

**9**

| ❙❋❯❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | sinclair researched |<br />

The ZX80/81<br />

In the beginning<br />

drawback and very soon, Sinclair started to sell 3K RAM expansion packs. As<br />

prices for memory started to fall at the beginning of the 80s, Sinclair later<br />

brought out a 16K expansion module. Around the world, the ZX81 price mark<br />

broke barriers at $199 in the USA and Dmk 498 in Germany.<br />

Version 2.0<br />

It all really got started in January 1980. This was when Sinclair<br />

Research announced a new computer engineers had been working on<br />

since May the previous year. The Sinclair ZX80 came to life in<br />

February, when the first kits started to sell at computer fairs. This was not Clive<br />

Sinclair’s first venture into selling computers; his previous MK14 kit had sold<br />

well, but nothing like the demand for the ZX80. In total, some 50,000 of these<br />

first stepping stones to modern computers were sold. Not as many as you would<br />

perhaps imagine, but enough to start the computer craze in the UK.<br />

In white moulded plastic, the ZX80 could be bought in kit form (£79.95) or<br />

pre-built and ready to run (£99.95). Advertising in major national newspapers<br />

brought the computer to the attention of many who saw it as the future and<br />

something educational to buy for their children. Sales took off and hundreds of<br />

children throughout the country got their first taste of BASIC programming.<br />

However, all was not as you would expect. The ZX80 could only do integer<br />

mathematics. Decimal points where unheard of. Although this sounds strange<br />

today, the Sinclair BASIC, which was written by John Grant of Nine Tiles, had to<br />

be squeezed onto a 4K ROM chip. The machine’s limited memory was a real<br />

1981 saw the release of Sinclair’s improved ZX81. It was launched in March, in a<br />

blaze of television and media publicity. Similar in looks, the black-cased ZX81<br />

had hardware mainly designed by the ZX80 designer, Jim Westwood. The<br />

upgraded 8K ROM finally had a decimal point for its mathematics routines. For<br />

those who had bought a ZX80, they could buy an 8K ROM upgrade, although it<br />

was the end of Autumn before the final maths bugs had been sorted out. The<br />

new machine retailed for an unprecedented £69.95. This low price was mainly<br />

due to the Ferranti-produced ULA (Uncommitted Logic Array) which reduced the<br />

number of components and, therefore, the overall cost. The ZX80 contained 21<br />

chips, whereas the ZX81 contained just four chips, including the RAM and<br />

processor.<br />

The ZX81 possessed 1K of RAM, but for £29.95 you could purchase a 16K<br />

RAM pack. However, these expansion packs had one major design fault. To save<br />

money, the computers did not have a socket for expansion. They relied on the<br />

circuit board itself. Copper circuit tracks ran to the edge of the board. The<br />

expansion packs had to grip the original board and make a connection. During<br />

>Official<br />

add-ons.<br />

The Sinclair ZX Printer came to market in time for Christmas 1981, costing a<br />

very reasonable £49.95 (this later rose to £59.95 because of rising<br />

production costs). At the time, 9 pin dot matrix printers typically sold for<br />

£200 to £300. The printer used aluminium coated black paper. The stylus<br />

was electrically charged and this burnt away the aluminium, leaving the<br />

black paper to show through. At 32 characters wide (about 4in), the black<br />

on silver output was mainly used for printing program listings. The printer<br />

may have been cheap, but the paper was not, costing £12 for five small<br />

rolls. Fortunately for businesses attempting to use the ZX81, third party<br />

manufacturers produced interfaces that allowed a standard Centronic printer<br />

to be connected. By the time the Spectum arrived, the ZX Printer had almost<br />

been phased out, but it could still be connected to the new computer.<br />

1983 saw the launch of the Sinclair Interface 1. This was a small<br />

expansion module that raised the back of the spectrum. Along with two 100<br />

baud network ports and a real RS-232-C port for either printers or modems,<br />

the Interface 1 had a new connection port. This port allowed the connection<br />

of up to eight Sinclair’s Microdrives. The ZX Microdrive was a cheap mass<br />

storage device using an endless loop of 1.9mm video tape. Each unit was<br />

priced at £49.95, although £79.95 got you one plus the Interface 1. Between<br />

85k and 100K could be stored on a cartridge, and at 15k per second, that<br />

meant that games could be loaded very quickly. At the time it was seen as a<br />

cheap, reliable form of storage, but the new 3.5in disks slowly ate the<br />

market and third party manufacturers produced floppy drive interfaces.<br />

The Sinclair Interface 2 was also released in 1983. This was Sir Clive’s<br />

answer to the boom in console sales, and the small unit (priced at £19.95)<br />

contained two joystick ports and a ROM cartridge slot. Several cartridge<br />

games were released, including a quartet of classics titles from Ultimate, but<br />

they were priced at £15 each! Granted, they loaded quicker than their<br />

cassette-based counterparts, but who would pay three times more for that<br />

privilege? Another blow was that the ROM cartridges could only store 16K<br />

games, so the growling library of 48K games was not supported.<br />

**10**

the design phase, this was reasonable, but in practice, the memory expansion<br />

was prone to lose some contact, so your carefully typed-in program was at risk<br />

if anything was to knock the pack. And as the keyboard was nothing but a<br />

membrane, it was possible to press a key just a little too hard and the whole<br />

machine would move enough to crash. Although a major headache for users, this<br />

did lead to the creation of many a small company, attempting to solve the<br />

problem. These solutions ranged from blu-tak or velcro fasteners to metal strips<br />

and screws which bolted onto the expansion pack.<br />

The ingenuity of users started to show too. Tired of a black and white<br />

television screen? Just buy a sheet of green plastic film and you have a green<br />

screen monitor just like the expensive business computers! Hardware peripheral<br />

manufacturers sprung up in almost every garden shed, which was remarkable<br />

because most were garden sheds. Memory could be added to a massive 1Mb,<br />

although this relied on memory paging. Memotech produced a hi-resolution<br />

expansion box. Moving-key keyboards were popular, along with joysticks and<br />

even digitising tablets.<br />

Gathering pace<br />

The success of the ZX81 snowballed. After sales reached a certain point, there<br />

were enough young wannabe programmers desperate to make the next big<br />

selling hit. These programs increased the software catalogue and so in turn<br />

persuaded others to buy the machine. Christmas 1981 saw thousands of parents<br />

spending the whole of the festive season trying to get the level on a tape<br />

recorder just perfect to be able to load in a program off a cassette tape.<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong>s sprung up quickly to try and cater for the demand, with many<br />

printing program listings. Nobody thought it was strange to type in a<br />

hexadecimal computer listing that was an obvious photocopy from someone’s<br />

Sinclair thermal printer, save it to cassette and hope it did something useful<br />

before the machine crashed and lost everything!<br />

Pre-recorded software was the wise alternative. The Sinclair ZX Software arm<br />

produced a range of cassette-based teaching aids but these were not successful.<br />

Games, however, did rule. With its very limited graphics, it was possible to play<br />

Space Invaders as long as you had no problem pretending the chunky graphics<br />

were alien-like. There was some innovation though, with 3D Monster Maze being<br />

one of the original first-person adventures.<br />

Within two years, over one million ZX81 computers had been sold, some<br />

300,000 via Sinclair’s own mail order service. Of course, some people never give<br />

in. You can still buy original kits, so never mind collecting, start using! The ZX<br />

Team are a user group of (friendly) fanatics who still support the ZX80/81 and<br />

their clones. Fancy making a portable? Visit their site (www.zx81.de) and go to<br />

the projects page.<br />

A selection of official Sinclair<br />

peripherals<br />

**11**

| ❙❋❯❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | sinclair researched |<br />

The ZX -<br />

Spectrum<br />

The glory days<br />

Having turned the nation into a computer literate frenzy, 1982 saw Sir Clive Sinclair<br />

reach a pinnacle. He had been snubbed by the BBC, who chose Acorn Computers<br />

(set up by Chris Curry who had once worked for Sinclair) to build a computer<br />

endorsed by the national TV broadcaster. At £400, the Acorn BBC models A and B<br />

were a little beyond the reach of most, and Sinclair planned his revenge. In another<br />

glare of camera lights, he announced the new Sinclair ZX Spectrum. The first<br />

noticeable feature was colour. Then there was the price. £125 bought the 16K RAM<br />

version or £175 for the 48K model (within six months, the 16K model dropped to<br />

£99.95, making the first colour computer available for under £100). Although not<br />

equipped with all the interface ports of the BBC, the price difference was to be a<br />

huge factor.<br />

At the launch, Sinclair’s marketing team had learned some new tricks. They<br />

constantly referred to the educational software that would be available; a brilliant<br />

move as every child in the country could try to persuade their parents that the<br />

computer could help with school work. What parent could take the chance that their<br />

child could be left behind? The first few days saw such a buying frenzy that the<br />

>Sinclair<br />

overseas.<br />

Sinclair mail order department could not keep up with demand. These delays were<br />

to become part of folklore and the mail order department was never able to shake<br />

its less than stellar image.<br />

Almost immediately, industries sprung up to support the Spectrum. <strong>Magazine</strong>s<br />

were launched, software companies created almost nightly, and hardware add-ons<br />

flourished. Most people bought the 16K version as you could later upgrade to 48K<br />

by slotting in extra RAM chips for about £50. Programmers had by now spent two<br />

years learning how to cram code into 16K. This was the machine they had been<br />

waiting for.<br />

After Christmas, school playgrounds became a battle field of rivalries. Parents<br />

who had paid extra to buy a BBC or one of the newly imported Atari computers<br />

found their child outnumbered by the Spectrum-owning kids. This rivalry intensified<br />

with each new machine launched, forcing the owners to become inventive in their<br />

programming. Other computers could boast better hardware features and facilities.<br />

Spectrum users made up for this by using brilliant software hacks. Every time a new<br />

program hit the shop shelves it was eagerly bought and carefully reverse-engineered<br />

to learn just how the programmer had implemented the new features. Disassembler<br />

programs were common, and no-one thought anything wrong with taking other<br />

programmer’s code to pieces in pursuit of learning.<br />

Profit from piracy<br />

No-one worried about reverse engineering because a much bigger existed.<br />

Software was sold and stored on cassette tape, and any child could connect a<br />

Starting with the ZX81, the machines were being manufactured by the<br />

American Timex company in their Dundee factory. This gave Sinclair a way<br />

into the American market. Timex re-badged the ZX81 and Spectrum and sold<br />

them in the States as the TS1000 and TS2000 respectively.<br />

Other countries saw the success and a few started to make their own<br />

cloned versions. Brazil and Argentina were not part of the official Sinclair<br />

distribution and many unofficial clones were produced. These ranged from the<br />

MicroDigital TK82 clone of the ZX80 to the Argentinean Czerweny Electronica<br />

CZ2000+ Spectrum clone. Hong Kong followed with a Spectrum derivative<br />

called the Lambda 8300. However, most clones came from behind the iron<br />

curtain. The cold war meant that Sinclair could do little about copyright. From<br />

Slovakia came the Didaktik Gama. It is actually still possible to find versions<br />

for sale, with the Didaktik Kompakt having a built-in disk drive! Russia<br />

naturally went a little further and produced the Hobeta or Hobbit Personal<br />

Computer in Leningrad, with a high degree of compatibility and a<br />

considerably improved spec: 64K RAM, dual 5.25in disk drives, three joystick<br />

ports, both TV and RGB monitor output, parallel and serial ports. It was<br />

mainly sold for use in Russian schools.<br />

The ultimate Spectrum though was the Scorpion ZS-256 – a Z80B 7Mhz<br />

CPU with a huge 256K of RAM. It came with a disk drive controller and TR-<br />

DOS. More recently in 1996, an upgraded Spectrum called the Sprinter arrived,<br />

which could run both TR-DOS and MS-DOS!<br />

MicroDigital released a whole<br />

host of unofficial Spectrum<br />

clones<br />

**12**

couple of tape recorders together and run off a copy or two. You could buy the<br />

latest game and within a day, have swapped it at school for dozens of other<br />

games. Although illegal, everyone knew that you could quickly have a huge<br />

library of programs. Buy a Spectrum and stock up on C90 tapes, and you could<br />

end up with hundreds of the cutting edge programs for a fraction of the price<br />

compared to BBC owners. Acorn hit back the only way they could – by<br />

introducing add-ons such as 5.25in disk drives. Sadly these were so expensive<br />

that third party manufacturers produced their own, adding to confusion over<br />

single or double sided and single or double density. Spectrum users just bought<br />

double tape players – so their parents could also copy music – and more C90s!<br />

The early days saw a host of innovative games as each new feature of the<br />

Spectrum was discovered. Having thousands of bedroom programmers meant<br />

that the market was ruthless. Thousands of games were written, and as piracy<br />

was rife, only the very best sold. For all of the features of modern computer<br />

games with extensive graphics and dialogue, the ultimate test is playability.<br />

Limited hardware meant that, to survive and make a million, the games had to<br />

grab your attention and be instantly playable. The list is impressive. Early<br />

success came to companies like Imagine, with tales of young programmers<br />

earning thousands. After its spectacular collapse, many left to form other<br />

companies such as Ocean. Probably the best known software house was Ashby<br />

Computer Graphics which traded under the name of Ultimate Play The Game. It<br />

produced classics such as Jetpac, Atic Atac and Knight Lore. As a typical game<br />

took some six minutes to load, it soon became common for a splash screen to<br />

be loaded before the rest of the program. Many software houses at the time<br />

hired artists just to produce these images, which due to the limited palette and<br />

resolutions, were in fact real works of art.<br />

Third party hardware manufacturers flourished, and fought to out do one<br />

another with inventive add-ons, including graphics tablets, full-sized printers,<br />

alternative storage media and, due to the popularity of games, joysticks. Where<br />

the rival BBC had analogue joysticks requiring expensive potentiometers, the<br />

Spectrum made do with cheaper contact switches.<br />

When it came to the keyboard, Sinclair had learned valuable lesssons from<br />

the previous computers. The flat membrane keyboards had been poorly thought<br />

of, and in an effort to reduce cost but improve features, the Spectrum used a<br />

membrane as the contacts, but this time had rubber blocks for the keys. The<br />

‘Dead Flesh’ keyboard gave a little response back, but many add-on keyboards<br />

were developed and sold. With so much potential for third party fixes, the<br />

system was as cheap as you were willing to pay. You could live with the basic<br />

model or spend as much as your piggy bank could afford to buy yourself a<br />

better computer.<br />

>Super<br />

Spectrum.<br />

No, not the SAM Coupe, but rather the Spectrum +3e. This souped-up<br />

Speccy is the work of Garry Lancaster. He’s basically upgraded the +3<br />

ROMs, fixing bugs and adding new features. The improvements range from<br />

the small (you can now change the colours in the editor) to the significant<br />

(the introduction of user-defined text windows). Best of all, the enhanced<br />

ROMs allow you to connect a standard IDE hard drive to your Spectrum +3<br />

(or +2A)! Obviously you need to construct a suitable interface, but if your<br />

soldering skills are up the scratch, the new software will do the rest. It’s<br />

even possible to build an interface that plugs directly into the Z80 socket,<br />

so the connector sits neatly inside the casing. Lancaster reports that he’s<br />

connected drives as big as 8Gb, and he sees no reason why you can’t<br />

connect even bigger drives. For more information about the Spectrum +3e,<br />

including details on how to upgrade your ROMs with the new code, visit<br />

Garry’s Web site at www.zxplus3e.plus.com.<br />

Upgrade your Spectrum +3 to support<br />

a standard IDE hard drive<br />

**13**

| ❙❋❯❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | sinclair researched |<br />

Broadening the range<br />

Sinclair was on a roll, with Spectrums being shipped as fast as they could be made.<br />

The Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, presented one to the Japanese leader, and<br />

Clive Sinclair was knighted in 1983.<br />

In October the following year, the Sinclair ZX Spectrum+ was produced. This was<br />

similar to a software patch. It was still the same machine but had a working<br />

keyboard, where the keys actually moved. By 1985, sales started to slide and so the<br />

Spectrum+ was again improved to produce the ZX Spectrum 128. This new machine<br />

had the keyboard of the Spectrum+ and a new sound system, with three channels<br />

and seven octaves, plus the ubiquitous 128K RAM. The new 128 BASIC did away<br />

with the one-touch entry system of the original version, although you could still<br />

switch to 48K compatibility mode if needed. Britain finally saw the model in<br />

February 1986, but by then Sinclair was on the way out. A few months later, Amstrad<br />

took over Sinclair after the company sustained heavy financial losses, accredited to<br />

the doomed Sinclair C5. The Spectrum 128 was soon dropped as Amstrad<br />

consolidated the operation, making it something of a rarity today.<br />

In 1987, Amstrad sold the Taiwanese-manufactured ZX Spectrum +2. This was<br />

basically a Spectrum 128 stuffed inside Amstrad’s own CPC 6128 case. With the builtin<br />

tape player, it was perfect for playing games and marketed more as a console<br />

than a computer (early packs even came bundled with a light gun). Development<br />

continued but at a slower pace. 1988 saw the release of the Spectrum +3. This was<br />

basically a +2 with a built-in disk drive replacing the tape player. It also included an<br />

upgraded version of BASIC, complete with new disk operating commands. At £250,<br />

the +3 was not a big seller. This was partially due to the unusual choice of disk<br />

format. Amstrad opted for its own 3in disk drive rather than the standard 3.5in<br />

floppy drive that is still used today. The +2 was still popular though, and the<br />

upgraded +2A model also appeared in 1988. This was basically a +2 with +3 BASIC,<br />

and a port to connect a standalone disk drive that was never released. This model<br />

outlived<br />

The<br />

the +3 and remained<br />

Sinclair<br />

on sale well into the early 90s.<br />

QL<br />

Sir Clive gets serious<br />

Riding on the wave of success from the ZX Spectrum, Sinclair decided that the<br />

business market was the next big thing. This time, it was not to be a super<br />

Spectrum, but rather a leap forward. The Sinclair QL (Quantum Leap) was<br />

marketed as the first 32-bit business machine to retail for under £400.<br />

The first improvement was the memory. Chip prices were slowly falling so 128K<br />

on-board was possible. Ending Sinclair’s use of the Z80 processors, the QL used<br />

the new Motorola 68008 chip, although once again with only a 16-bit bus. The<br />

ability to connect a real computer monitor or television offered the best of both<br />

worlds, while the twin Microdrives would provide rapid storage for programs and<br />

data. How could it go wrong?<br />

The launch was dogged by the fact that the hardware was not quite complete.<br />

The new QDOS operating system did not fit into the ROM and so initial models<br />

had a ‘Dongle’ circuit board. This was complicated by a disastrous mail order arm<br />

>Software<br />

support.<br />

Every QL was sold with four business programs written by Psion, who itself<br />

went on to produce handheld computers. Quill was the standard word<br />

processing package while Archive was a database, capable of real business<br />

use and scripting. Abacus introduced spreadsheets, only to be let down by<br />

Easel for graphical output. This was not really down to the software, but the<br />

fact that QLs only had four colours (Black, White, Red and Green) made<br />

graphics somewhat limited.<br />

Games did not take off for the QL, which was both its downfall and its<br />

saving grace. Without games it failed to hit the mass market. No games<br />

meant that it was used in businesses throughout the country and further<br />

afield. Software was written and is still being improved. The latest commercial<br />

software, released just a few weeks ago, is called Launchpad. This is a<br />

program<br />

The<br />

launcher and<br />

Z88<br />

general GUI for all the differing operating systems.<br />

After Sinclair had been bought by Amstrad, Sir Clive was not quite out of the<br />

market. He formed Cambridge Computers which manufactured the very<br />

portable Z88. This was really a follow on to the Grundy NewBrain designed<br />

by the Sinclair Radionics company, which was released in 1980 and would<br />

possibly have been the BBC computer had ownership not changed before<br />

launch. The Z88s are still favoured by some researchers as the rubber<br />

keyboard is silent, so it can be used in libraries and recording studies<br />

throughout the world. Oddly, the operating system is very similar to that of<br />

the Acorn BBC.<br />

**14**

which failed to supply machines. The independent user group (QUANTA) was<br />

formed before anyone managed to get hold of a machine and even produced a<br />

magazine before machines were shipped. At the same time, the 3.5in disk drive<br />

arrived. Previously, the Microdrive was seen as a viable alternative to cassette<br />

tape, capable of holding 100K on each continuous loop of tape. Drives of 3.5in<br />

killed this idea so that very soon, any self-respecting QL user had upgraded by<br />

adding a third party disk interface.<br />

Launching the Sinclair C5 tricycle around the same time did not do the name<br />

of Sinclair any favours. Slowly, the rise of the Intel/IBM PC eroded the market.<br />

Over 100,000 QLs were eventually sold. BT, with Merlin, produced a clone called<br />

the Merlin Tonto, and ICL, which later became part of the Fujitsu empire, made a<br />

version called the One-Per-Desk. These two models had built in telephones and<br />

modems along with being made in a dark beige colour, rather than the now<br />

standard Sinclair black. Other compatibles followed including the CST Thor. By<br />

1986 Sinclair’s fortunes had reduced to the state where Amstrad took over its<br />

business. Amstrad, ever one to market a good idea, stopped production of the QL<br />

and focused on improved versions of the Spectrum.<br />

The QL lives!<br />

The network sockets never worked as stated, but the added RS-232-C ports did<br />

leave an opening for attaching a modem as well as a printer. Cheap 1200/75 baud<br />

modems allowed many people to use bulletin boards for<br />

communications. Online communities developed and dedicated users<br />

grouped together. Just like a PC has evolved from an XT to the modern<br />

3GHz machine, the QL has since evolved both in hardware and software.<br />

The user group is still going strong, with monthly meetings in various<br />

parts of the country.<br />

After disk drive interfaces and memory expansions, the QL really<br />

took the hearts of its users with accelerator cards from Miracle Systems.<br />

Upgrading the processor and RAM was then usually followed by ROM<br />

changes. Full keyboards, mice and proper disk drives followed. Never<br />

mind 1.44Mbs per disk – later QLs used ED disks capable of storing<br />

3.2Mbs each! Hard drives eventually came and the latest models now<br />

being produced are the Q40 and Q60, which use faster processors and<br />

are housed in standard PC cases. These can run either the QDOS<br />

operating system or Linux.<br />

QDOS survived because the SuperBASIC was more like a Pascal<br />

language in some respects. Multitasking was the norm. Improved<br />

ROMs became available along with additional software toolkits.<br />

Finally, a replacement operating system was produced which is now<br />

called SMSQ/E. ✺✯*<br />

Down but not out. Sir Clive strikes<br />

back with the Z88 portable computer<br />

>Sinclair<br />

model<br />

specs.<br />

ZX80<br />

NEC 780C-1 (Zilog Z80A compatible)<br />

3.25MHz<br />

4K ROM<br />

32x24 characters<br />

64x48 (Quarter Character blocks) graphics<br />

Black and white via a UHF TV aerial adapter<br />

No Sound<br />

Microphone and earphone sockets at 250 baud<br />

Expansion bus<br />

Touch-sensitive, smooth-membrane keyboard<br />

ZX81<br />

NEC 780C-1 (Zilog Z80A compatible)<br />

3.25MHz<br />

4K ROM<br />

32x24 characters<br />

Black and white via a UHF TV aerial adapter<br />

No Sound<br />

Microphone and earphone sockets at 250 baud<br />

Expansion bus<br />

Touch-sensitive, smooth-membrane keyboard<br />

ZX Spectrum<br />

3.54MHz Zilog Z80A<br />

16K or 48K RAM<br />

32x22 text 256x192 8 colour graphics<br />

1 channel 5 octave range sound<br />

Dead Flesh Keyboard<br />

ZX Spectrum+<br />

3.54MHz Zilog Z80A<br />

48K RAM<br />

32x22 text 256x192 8 colour graphics<br />

1 channel 5 octave range sound<br />

Tactile Keyboard<br />

ZX Spectrum 128<br />

3.54MHz Zilog Z80A<br />

128K RAM<br />

32x22 text 256x192 8 colour graphics<br />

3 channel 7 octave range sound<br />

Tactile Keyboard<br />

Joystick ports<br />

RS-232-C<br />

Midi Out<br />

ZX Spectrum+2/+2A<br />

3.54MHz Zilog Z80A<br />

128K RAM<br />

32x22 text 256x192 8 colour graphics<br />

3 channel 7 octave range sound<br />

Tactile Keyboard, Grey casing<br />

Built-in tape recorder<br />

Joystick ports<br />

RS-232-C<br />

Midi Out<br />

ZX Spectrum+3<br />

3.54MHz Zilog Z80A<br />

128K RAM<br />

32x22 text 256x192 8 colour graphics<br />

3 channel 7 octave range sound<br />

Tactile Keyboard<br />

3in disk drive<br />

Joystick ports<br />

RS-232-C<br />

Midi Out<br />

Sinclair QL<br />

7.5 MHz<br />

Motorola MC68008P<br />

128K RAM<br />

48K ROM<br />

42x25 text, 256x256 8 colours, 512x256 4 colours<br />

2 joystick ports<br />

2 RS-232-C ports<br />

TV and monitor connections<br />

2 100K Microdrives<br />

2 network sockets<br />

**15**

| ❙❋❯❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | lord of the rings |<br />

**18**

With The Return of the King<br />

<br />

>return<br />

of the<br />

rings.<br />

From simple arcade<br />

games to complex<br />

adventures and sprawling<br />

battle sims, The Lord<br />

of the Rings has been a<br />

major source of<br />

inspiration for software<br />

developers for over 20<br />

years. Martyn Carroll<br />

sets off on a journey<br />

to uncover the many<br />

games based on<br />

Tolkein's epic work<br />

movie still raking in cash at<br />

cinemas up and down the<br />

country, and the extended DVD<br />

release due in November, it seems<br />

that no mere mortal will be able to<br />

escape the Lord of the Rings for the<br />

foreseeable future.<br />

You won’t find respite by<br />

playing videogames either,<br />

because EA has recently<br />

released its Return of the King tiein<br />

and are following it up later in<br />

the year with Lord of the Rings<br />

Trilogy, a game based on all<br />

three films.<br />

In a separate licensing deal, Vivendi<br />

Interactive are also releasing<br />

PC games based on the<br />

original book; the War of<br />

the Ring is out now<br />

and The Battle for<br />

Middle-earth is due out<br />

in the summer. The<br />

games are coming thick<br />

and fast, but it’s not<br />

the first time players<br />

have stepped into the<br />

shoes of their favourite<br />

Tolkien character and<br />

walk the world of<br />

Middle-earth.<br />

**19**

| ❙❋❯❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | lord of the rings |<br />

Two early games that were<br />

loosely based on The Lord<br />

of the Rings<br />

The bold and<br />

the not so<br />

beautiful<br />

Back in the early 80s, long before<br />

the fledgling computer games<br />

market could be classed as an<br />

industry, publishers could not justify<br />

licensing costs so they dreamt up<br />

unofficial yet blatant titles. Games<br />

with titles like Return of the Jedy<br />

and Invasion of the Body Snatchas<br />

were common place. In 1982,<br />

Postern Software released the<br />

more subtly titled Shadowfax, an<br />

arcade game named after<br />

Gandalf’s horse. Originally<br />

released on the Vic 20, and later<br />

appearing on the Spectrum and<br />

C64, the game saw the player<br />

ride the titular beast into battle<br />

against a never-ending stream of<br />

Black Riders. By hitting the fire<br />

button you could zap Sauron’s<br />

servants with well-placed<br />

lightning bolts. There was no<br />

level structure as such, and the<br />

riders just kept on coming,<br />

making Shadowfax something of<br />

a one trick pony. The animation<br />

of the horses was excellent, however,<br />

being based on Eadweard Muybridge’s<br />

famous photographs.<br />

Shadowfax is a solid gold classic<br />

when compared to Moria – a game<br />

released in the same year on the<br />

Spectrum, C64 and Oric-1. You played<br />

Gandalf in this too and your aim was<br />

to retrieve Durin’s ring from the mines<br />

of Moria. It sounded intriguing until<br />

you realised Moria was depicted as a<br />

11x11 square grid and your position<br />

was marked with a letter G. As you<br />

moved from square to square you<br />

would stumble upon enemies. Here<br />

you could choose to fight or run and<br />

that was about as interactive as the<br />

game ever got.<br />

As Moria shows, developers were<br />

never going to successfully visualise<br />

Tolkien’s tale with these primitive<br />

machines, so the best games came in<br />

the form of text adventures. These<br />

games where often characterised by<br />

their complexity, although half the<br />

time, players struggled with the syntax<br />

rather then the puzzles themselves.<br />

Many games required you to enter<br />

exact phrases to progress, resulting in<br />

much thesaurus thumbing.<br />

The very first text adventure,<br />

cunningly entitled Adventure, was<br />

loaded with Tolkien references. This<br />

influential game toured University<br />

campuses throughout the 1970s,<br />

eventually turning up on home<br />

computers (as Colossal Adventure) in<br />

1981, courtesy of Level 9 Computing.<br />

By now it had gathered even more<br />

Tolkien lore, including trolls, elves<br />

and a volcano that was strikingly<br />

similar to Mount Doom. The game<br />

spawned two sequels, Adventure<br />

Quest and Dungeon Adventure, and<br />

the three adventures came to be<br />

known as the Middle-earth Trilogy.<br />

The games were later re-released<br />

under the Jewels of Darkness title<br />

and all of the Tolkien references were<br />

removed. This was no doubt due to<br />

the fact that Melbourne House had<br />

licensed Lord of the Rings from the<br />

Tolkien estate.<br />

Following on from their successful<br />

adventure game based on The Hobbit,<br />

Melbourne House released Lord of the<br />

Rings Game One in 1985 on Spectrum,<br />

C64, Amstrad CPC, BBC, PC, Apple II<br />

and Mac. The game covered The<br />

Fellowship of the Ring (in the US the<br />

game was released as The Fellowship<br />

of the Ring Software Adventure), and<br />

was split into two parts like the book.<br />

In what was a first for an adventure<br />

**20**

The rather cheeky Middle-earth Trilogy from Level 9 Computing<br />

game, you could choose which<br />

character you wanted to play from<br />

Frodo, Sam, Pippin and Merry. Your<br />

selection didn’t make a great deal of<br />

difference, but if you managed to<br />

complete the game (no small feat) you<br />

could play through again from<br />

different perspectives.<br />

The game began in The Shire,<br />

where you were able to explore the<br />

Hobbit’s homeland before setting off<br />

on your journey to Rivendell. In fact, it<br />

was possible to stray from the story<br />

and head in the opposite direction,<br />

over the Blue Mountains towards the<br />

forested planes of Harlingdon and the<br />

ocean beyond. So while the game<br />

followed the plot closely, it was<br />

possible to explore some of the places<br />

only mentioned in the book (or<br />

included on Tolkien’s map of Middleearth).<br />

The game threw in a number of<br />

unique plot twists too, so even fans<br />

were in for a few surprises. Saying<br />

that, at the time of release many fans<br />

were disappointed with the game,<br />

possibly because an in-depth<br />

knowledge of the book was not<br />

assumed. The text was riddled with<br />

grammatical errors too, making it look<br />

like a rushed job rather than a game<br />

that had been in development for 15<br />

months. On a more general note, the<br />

game cost a staggering £16! However,<br />

it did come in fancy packaging with a<br />

paperback copy of The Fellowship of<br />

the Ring thrown in.<br />

In 1988, Melbourne House released<br />

Lord of the Rings Game Two on the<br />

Spectrum, C64, Amstrad CPC, PC,<br />

Apple II and Mac. It was subtitled<br />

Shadows of Mordor and specifically<br />

covered book four of The Two Towers,<br />

following Frodo and Sam’s quest<br />

rather than Aragorn’s plotline. While<br />

not a great departure from the first<br />

game, it was certainly a lot more<br />

polished, with far fewer typing errors<br />

and improved graphics used to<br />

illustrate the text. Characters also<br />

displayed more independence. They<br />

would go off and do their own thing<br />

rather than follow you dumbly whilst<br />

singing about gold.<br />

The company always intended to<br />

release a trilogy of games and the<br />

final instalment duly appeared in<br />

1989. Subtitled The Crack of Doom, it<br />

covered the events in book six of The<br />

Return of the King, climaxing in the<br />

ring forging scene on top of Mount<br />

Doom. Unlike the first two adventures,<br />

you could only control Sam Gamgee<br />

but overall the game was a marked<br />

improvement over its predecessors. It<br />

was only released on the C64, PC and<br />

Mac, and rather strangely, the game<br />

was never released outside North<br />

America, The Tolkien Trilogy, released<br />

in 1989, actually consisted of The<br />

Hobbit and the first two Lord of the<br />

Rings games.<br />

Speaking<br />

volumes<br />

The PC and Amiga were home to the<br />

first fully graphical adventure game<br />

based on the book. It was entitled<br />

At £16, Game One was almost three times more than standard<br />

games at the time!<br />

**21**

| ❙❋❯❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | lord of the rings |<br />

Game Two improved on its<br />

predecessor with better<br />

graphics and clearer<br />

descriptions<br />

One of the rarest 2600<br />

prototypes is now<br />

available for download<br />

The third game in the trilogy<br />

was only ever released in the<br />

US, making it something of a<br />

novelty for UK fans<br />

Lord of the Rings Vol 1 and was<br />

released by Interplay in 1990. It was<br />

similar to the early Zelda and Final<br />

Fantasy games in many respects. The<br />

action was viewed from overhead and<br />

the gameplay revolved around slaying<br />

enemies (wolves and wargs at first,<br />

spiders and sorcerers later on) and<br />

solving tricky puzzles. If you were<br />

stumped, you could always gain clues<br />

by engaging the local inhabitants in<br />

conversation. You started out<br />

controlling just a single character<br />

(Frodo) but as you progressed you<br />

were able to enlist the services of<br />

various dwarves, elves and humans.<br />

With a party of up to ten in tow, you<br />

could stage some spectacular battles<br />

later on. Lord of the Rings Vol 1 was<br />

an entertaining game which has aged<br />

far better than the earlier text<br />

adventure. However, like the<br />

Melbourne House games, the plot was<br />

not too linear, meaning that the player<br />

was not forced to complete tasks in a<br />

strict order (some tasks could be<br />

avoided completely).<br />

Interplay followed up the game<br />

with an enhanced CD version (which<br />

featured scenes from Ralph Bakshi’s<br />

animated movie), a SNES version and<br />

a very similar PC-only sequel titled<br />

Lord of the Rings Vol 2: The Two<br />

Towers. The follow-up shifted the<br />

emphasis from combat to puzzle<br />

solving and was better for it. This<br />

SNES version was interesting<br />

because while it shared the same<br />

name as the PC/Amiga version, it<br />

was a completely different game. It<br />

supported up to five players for a<br />

start, and there were loads of silly<br />

errands to run and mind-boggling<br />

mazes to explore. You could interact<br />

with non-playable characters, and<br />

level-up the members of the<br />

fellowship, but this was very much a<br />

light RPG. The game ended abruptly<br />

too, and the proposed SNES sequel<br />

never appeared.<br />

The same fate befell the final part<br />

of the PC trilogy. Work was well<br />

underway on Vol 3 when it was<br />

unceremoniously pulled. The third<br />

game was to be more of a strategy<br />

game than an RPG, and it was very<br />

nearly released as part of Advanced<br />

Dungeons and Dragons’ Forgotten<br />

Realms series before it was canned<br />

altogether.<br />

**22**

war games.<br />

Melbourne House marched out War in Middle Earth in 1988, shortly before<br />

the release of The Crack of Doom. This turn-based strategy game was<br />

developed by Mike Singleton, author of Shadowfax and The Lords of<br />

Midnight (which was heavily inspired by The Lord of the Rings itself).<br />

Using an icon-driven interface, you had to guide Frodo and the fellowship<br />

from The Shire to Mount Doom. Along the way you would become<br />

embroiled in battles with Sauron’s armies. The removed perspective<br />

distanced the player from the characters, who were, after all, just pixels on<br />

a huge playing field, yet the game certainly emphasised the epic nature of<br />

the novel. It was ahead of its time too, predating the similar Dune games<br />

by at least two years. The game was originally released on 8-bit machines<br />

(including the MSX) but later appeared on the PC, Amiga and Atari ST.<br />

These later versions benefited from enhanced visuals, including graphic<br />

sequences which showed the characters preparing for battle.<br />

Beam Software, the Australian owners of Melbourne House, released Riders<br />

of Rohan on PC in 1990. This strategy game was similar to War in Middle Earth<br />

and began with the battle for Helm’s Deep. There were a number of units you<br />

could utilise, including Frodo and Aragorn, but the battle engine was on the<br />

simplistic side. Besides making tactical decisions, there were also several action<br />

scenes in which you battled against orcs, either firing arrows as Legolas or<br />

swinging your axe as Gimli.<br />

The Interplay games used a series of stills to drive<br />

the story<br />

Dead and<br />

buried?<br />

There is hope that Vol 3 may<br />

surface some time in the future,<br />

especially as a Lord of the Rings<br />

game written for the Atari 2600 has<br />

recently surfaced. This unreleased<br />

prototype, subtitled Journey To<br />

Rivendell, was originally scheduled<br />

for release in 1984 by Parker<br />

Brothers but never materialised,<br />

even though box artwork and screen<br />

shots appeared in one of their<br />

release catalogues at the time.<br />

Excited fans who phoned Parker<br />

Brothers were told that the game<br />

had sold out to cover up the fact<br />

that it had never been released. The<br />

prototype available on the Web is<br />

clearly unfinished, although some<br />

gameplay elements have been<br />

implemented. For instance, when the<br />

black riders attack, you can wear<br />

the ring to become invisible and<br />

dodge their attack.<br />

All this is a long way off the<br />

licences available now, but then<br />

again, both The Two Towers and The<br />

Return of the King games from EA<br />

are little more than polished versions<br />

of Golden Axe. Perhaps we haven’t<br />

travelled that far after all! ✺✯*<br />

These turn-based strategy sims<br />

were a welcome departure from<br />

the adventure games<br />

**23**

| ❙❋❯❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | miner willy |<br />

**24**

Hall of<br />

the Miner<br />

King.<br />

Miner Willy is one of<br />

the most recognisable<br />

game characters ever,<br />

having starred in Manic<br />

Miner and Jet Set<br />

Willy, two of the most<br />

successful and<br />

influential games of<br />

the 8-bit era. Martyn<br />

Carroll takes a walk<br />

down Surbiton Way,<br />

following in the<br />

footsteps of the<br />

intrepid explorer<br />

**25**

| ❙❋❯❙✄❍❇◆❋❙* | issue one | miner willy |<br />

When we first considered putting together a retro magazine, talk about content,<br />

readership and the business side of things always led, in a roundabout<br />

fashion, to Miner Willy. Nostalgia is infectious, and meetings would be filled<br />

with musings about back in the day, when games were good. The frequency with<br />

which Miner Willy entered the conversation was alarming. Indeed, talk to any<br />

videogame veteran about classic games and they’ll nearly always remember Manic<br />

Miner and Jet Set Willy with fondness. Miner Willy seems to strike a chord that cannot<br />

be ignored. And ignore it we won’t.<br />

Manic Miner<br />

Manic Miner was originally written for the Spectrum by Matthew Smith and released by<br />

Bug-Byte Software in 1983. Smith was 18 at the time, and it was only his second<br />

commercial game (Styx being the first). His main inspiration was a game written for<br />

the TRS-80 called Miner 2049’er.<br />

Miner Miner was immediately a huge hit, and perhaps the first Spectrum megagame.<br />

It was released at a time when many Spectrum games were simple affairs, often<br />

written in BASIC. In contrast, Miner was a stunningly smooth machine code creation. It<br />

was also big, featuring 20 screens, an almost unheard of number. And the best bit –<br />

each screen was completely unique, and home to a variety of weird and wonderful<br />

enemies. There were no alien ships or ghosts here. Smith introduced clockwork robots,<br />

mutant telephones and man-eating toilets!<br />

The game delivered a succession of firsts. It featured in-game music in addition to<br />

standard spot effects. Granted, the stunted version of In The Halls Of The Mountain<br />

Kings was continually looped, but it worked brilliantly. The game also featured an<br />

animated loading screen, with “Manic Miner” flashing as the tape played. Although this<br />

was a simple trick using flashing attributes, it was still a first for a Spectrum game.<br />

However, Manic Miner is perhaps best remembered for being the first very difficult<br />

game! You couldn’t complete this in an afternoon. In fact, you probably would never<br />

complete it. There was a fair chance you’d lose your three lives before Eugene’s Lair,<br />

and that was only a quarter of the way through the game. You could cheat, but this<br />

prevented you from completing the game properly.<br />

Following the success of Manic Miner, Smith left Bug-Byte and formed Software<br />

Projects with two associates. A legal loophole allowed Smith to take Manic Miner with<br />

him and re-release it as a Software Projects game. Subtitled Second Edition, the game<br />

was virtually identical. A small number of character sprites were changed, and some<br />

excellent new inlay art was created, but it was the same game. But fans needn’t have<br />

worried, as the true sequel was just around the corner.<br />

Jet Set Willy<br />

Jet Set Willy was scheduled for a Christmas 1983 release, but it slipped and eventually<br />

appeared in April 1984 (this would probably explain why the inlay says 1983 and the<br />

tape says 1984).<br />

>Perils of<br />

WillY.<br />

Neither Manic Miner or Jet Set Willy could be squeezed onto the Vic 20, so<br />

Software Projects set about creating a brand new Miner Willy adventure for the<br />

Commodore computer. The result was Perils of Willy, a Manic Miner clone with<br />

much cruder visuals. The aim was to jump from platform to platform, grabbing<br />

musical notes. Collect all the notes and you’d be taken to the next screen. It<br />

was a good step back from Manic Miner, and is only worth seeking out if you’re<br />

a Miner Willy completist.<br />

**26**

Jet Set Willy was not so much a sequel as a completely new game, in which Willy<br />

was let loose in a mansion containing 60 unique rooms. Unlike the original, there was<br />

no need to complete one screen in order to move onto the next. You could now<br />

explore! If one room looked a little tricky, why not leave it and come back later. If you<br />

were having trouble grabbing a tricky object, why not enter the room from the other<br />

side. The level of freedom offered was unprecedented, and the sheer scale was<br />

unparalleled. Jet Set Willy received rave reviews in the gaming press. Crash magazine<br />

called it “a high point in the development of the Spectrum game” and gave it 95%<br />

overall.<br />

Like Manic Miner, it was very unlikely that you would ever complete the game,<br />

despite the seven lives you began with. Just visiting every room in the game was<br />

sufficiently challenging. Software Projects sensed this, and offered a prize to the first<br />

person to telephone their offices and tell them how many glasses needed to be<br />

collected to complete the game. The winner would receive a case of Don Perignon<br />

champagne and a helicopter ride with Matthew Smith. The winners were Ross Holman<br />

and Cameron Else, who realised that the game couldn’t be completed, because an<br />

object in the First Landing couldn’t be collected. So you could only collect 82 objects<br />

instead of the required 83.<br />

Holman and Else won the prize nevertheless, and Software Projects released a<br />

Manic Miner. Perhaps the only<br />

game in existence with three<br />

different covers!<br />

**27**

series of POKEs that fixed the game. This is generally regarded as the first ever<br />

software patch! In order for the POKEs to work, Software Projects disclosed<br />

information on how to MERGE the basic loader. This opened up the possibility of<br />

changing the game in other ways, and quickly Jet Set Willy became the most hacked<br />

game ever. Your Spectrum magazine even included a special feature on hacking the<br />

game, including information on how to add a new screen in the place of a previously<br />

empty room. In fact, the game’s room format was so easy to exploit that two<br />

publishers, Spectrum Electronics and Softricks, released Jet Set Willy editors in 1984.<br />

These editing tools allowed users to design their own rooms, and many used them to<br />

create complete Miner Willy adventures. The best were Jet Set Willy III, an unofficial<br />

sequel by Michael Blanke and Arno P. Gitz, and Join the Jet Set, a surprisingly faithful<br />

spin-off by Richard Hallas.<br />

Jet Set Willy topped the charts throughout most of 1984, and rumours about secret<br />

rooms and the emergence of new hacks meant that it was never far from the pages of<br />

the specialist press. A sequel was inevitable, so it was no surprise when Software<br />

Projects announced that Smith was working on a new Miner Willy game. It was to be<br />

called the Megatree.<br />

Jet Set Willy II<br />

The Megatree (aka Willy Meets the Taxman) went on to become the stuff of legend.<br />

Some rumours suggest that Smith never even started work on the game, while others<br />

claim that a single screen was created before Smith walked out on Software Projects,<br />

The foot that squashed Willy<br />

was influenced by Monty Python's<br />

Flying Circus<br />

**28**

The Gaping Pit?<br />

apparently after an argument over royalty rates. The fact is that Matthew Smith never<br />

wrote a sequel. That job was left to Derrick Rowson.<br />

You can imagine the situation. The fans are crying out for a sequel and the man<br />

behind the series has gone AWOL. Software Projects needed something quick, and the<br />

solution was Jet Set Willy II: The Final Frontier. Released in July 1985, just over a year<br />

after the original, part II is best described as an enhanced version of Jet Set Willy.<br />

Rowson took all 60 of Smith’s rooms and added a further 71 rooms of his own,<br />

bringing the total number to 131. New rooms are dotted throughout the house, with<br />

the majority lying in the rarely-explored area beyond The Forgotten Abbey. However,<br />

the majority of new rooms were not in Willy’s house at all. In the original game, if you<br />

made your way to the very top of the house, and jumped up from The Watch Tower,<br />

you’d be looped back around to The Off License. But in the sequel, you’d appear in<br />

The Rocket Room. This would then take you to a space ship from which you could<br />

beam down to an alien planet.<br />

The main problem with Jet Set Willy II was that the new rooms were largely dull<br />

and boring. The author shared little of Smith’s imagination, and apart from a few nice<br />

touches (Willy in a space suit being one of them), the sequel was something of a<br />

missed opportunity. Crash agreed, giving the game 61% overall and saying “Good, but<br />

not much progress.”<br />

However, the sequel’s greatest strengths lay behind the scenes. Smith has<br />

squeezed every last byte out of the Spectrum to produce the original, and yet Rowson<br />

somehow managed to cram over double the amount of screens inside the 48K<br />

memory. To achieve this, Rowson created a compression algorithm that he used to<br />

scrunch the size of each screen. On the downside, this made the game much harder to<br />

hack, and very few modified versions of the sequel have appeared. ✺✯*<br />

Many rumours surrounded Jet Set Willy, with the main ones relating to<br />

supposed secret rooms. This seems to stem from a reference in Smith’s<br />

original code to a room called The Gaping Pit. Imaginations were on fire<br />

and the whole thing boiled over when Your Spectrum printed this letter<br />

from Robin Daines in issue seven:<br />

“Seeing your article in issue 4 about Jet Set Willy I felt<br />

compelled to write to you about some locations you’ve missed<br />

out. The Gaping Pit seemed the most obvious one, though<br />

even I haven’t visited it. Secondly, and more importantly, you<br />

omitted three major locations; here’s how you get to them.<br />

Wait on the bow till 11.45pm (Smith time), which may seem an awful long time to you<br />

swashbuckling Spectrummers. At that moment, a raft will get tossed up on a large wave and<br />

you must then jump on. It takes you to Crusoe Corner (a desert island to us landlubbers).<br />

Then you shin up a palm tree to arrive at Tree Tops – The Sequel, from which you catch the<br />

bird that travels up towards In The Clouds. From there you can control yourself all over the<br />

house (funny things happen when you try to enter<br />

the water or the Master Bedroom) and from that<br />

point, it should be possible to find The Gaping Pit<br />

(though I’ve not tried it myself). It also clobbers the ‘Attic<br />

Attack’ and makes it possible to go through baddies (fire puts<br />

you down where you are, so be careful) whereupon the bird<br />

disintegrates.”<br />

Your Spectrum countered with a sarcastic reply, about how they<br />

themselves had found even more secret rooms, but this was no doubt lost on<br />

countless readers, who waited and waited for that raft like Crusoe himself.<br />

This hoax became so famous that Derrick Rowson actually included the desert<br />

island in Jet Set Willy II. If you flick the trip switch, and then make it to The Bow<br />

without losing a life, the yacht will take you to The Deserted Isle.<br />

>Surbiton secrets.<br />

• The JSW in-game tune is “If I was a Rich Man” from Fiddler on the Roof,<br />

although the version of JSW that appeared on the They Sold a Million<br />

compilation features In The Halls Of The Mountain Kings from Manic Miner.<br />

JSW II also features the Grieg’s movement.<br />

• There’s a room in JSW called We Must Perform a Quirkafleeg. In case you’re wondering, a Quirkafleeg is an act that involves<br />

lying on the floor and kicking your legs out. It comes from a comic Smith used to read called The Furry Freak Brothers.<br />

• In the original JSW, you would die instantly if you entered We Must Perform a Quirkafleeg after visiting The Attic. It seems that<br />

the large caterpillar messed up some of the graphics, causing the crash. Software Projects released a POKE for this problem,<br />

although they claimed it was part of the game’s design! Apparently, after visiting The Attic, Quirkafleeg filled with deadly gas,<br />

forcing you to find an alternative route.<br />

• In JSW, the screen Nomen Luni is a mikey-take of the Nomen Ludi legend that appeared on Imagine’s plane-shooting game<br />

Zzoom. And if you look at that particular screen, you’ll see that a plane has indeed crashed into Willy’s mansion.<br />

• If you do manage to collect all 83 objects in JSW, Maria will let Willy retire to bed. But as soon as his head hits the pillow, he<br />

dashes to The Bathroom and throws up in the toilet! The ending to JSW II is even more devious, because it transports Willy to<br />

The Central Cavern. That’s right – the first screen from MM. Perhaps it was a recurring dream after all.<br />

• MM, JSW and JSW II were ported to many different machines, with some minor but interesting changes. For instance, the BBC<br />

Micro version of MM completely replaced the Solar Power Generator with a new screen called The Meteor Shower.<br />

Similarly, the Amstrad CPC version changed the layout of Solar Power Generator but the name remained the same.<br />

However, Eugene’s Lair was renamed Eugene Was Here.<br />

• The Commodore 16 version of Jet Set Willy only featured 20 screens, even though it was labelled “Enhanced<br />

Version”. The furthest to the left you could go was the Back Stairway and the furthest to the right was The Bridge. The<br />

C16 version of JSW II included over 80 screens, but the game was a four part multi-load<br />

• The Commodore 64 and Spectrum versions of JSW II were identical, expect that in the C64 port you could jump into<br />

the toilet at the start and visit several additional screens.<br />

• Software Projects commissioned Atari ST and Amiga versions of JSW in 1989. The company later canned both<br />

versions, but the Atari ST version was finished, and has since found it’s way onto the Web. It’s a very faithful remake of<br />

the Spectrum version, although there are two new rooms – Buried Treasure and Zaphod Says: DON’T PANIC!<br />

• Jester Interactive now own the rights to MM and JSW. A jazzed-up version of MM appeared on the GameBoy Advance in<br />

2002, and there are plans to port both games to mobile phones.<br />

**29**

| ❙❋❯❙✄❍❇◆❋❙*| issue one | mastertronic |<br />

>mastertronic,<br />

a history.<br />

It was announced in August last year<br />

that Mastertronic would be reborn as<br />

a software re-publisher. As its new<br />

owners look forward, we take the<br />

opportunity to look back at this<br />

classic software label. Anthony<br />

Guter, employee at the company from<br />

1985 to 1991, takes us back to the<br />

beginning, revealing how Mastertronic<br />

ripped up the rulebook and redefined<br />

the UK software market<br />

astertronic was<br />

founded in 1983<br />

by Martin<br />

Alper, Frank Herman and Alan Sharam.<br />

Based in London, the three businessmen<br />

had some financial backing from a<br />

small, outside group of investors. Unlike<br />

many of the company’s competitors in<br />

the games software market, the<br />

company was not set up by<br />

programmers seeking an outlet for their<br />

creations. Nor was it part of an<br />

established business with money to<br />

spare, dipping its corporate toe in the<br />

games industry’s rising tide.<br />

Mastertronic’s founders committed<br />

themselves to succeeding as publishers<br />

by selling games as cheaply as possible.<br />

Other publishers seemed to be<br />

concerned only with the process of<br />

creating the software and marketing an<br />

image – a strategy aimed directly at the<br />

consumer, with the hope that customer<br />

demand would somehow bring the<br />

games into the shops. In contrast,<br />

Mastertronic aimed its strategy at the<br />

distributors and retailers. If the games<br />

could be put on the shelves then a low<br />

**52**

selling price would do the rest.<br />

To this end, the core of the strategy<br />

was budget software – games priced at<br />

no more than £3, at a time when most<br />

decent software was priced at £6 or<br />

more. In fact, Mastertronic opted for<br />

£1.99 as the basic price. Both Alper and<br />

Herman had experience in the video<br />

distribution business, and they believed<br />

it possible to build up a reasonable<br />

market share at this low price. With the<br />

strategy in place, the company began<br />

trading on April 1st, 1984. It initially<br />

operated out of the back room of<br />

Sharam’s office, in the heart of London’s<br />

West End.<br />

Trading blows<br />

After the infamous videogame crash<br />

of 1983, a new generation of cheap,<br />

programmable computers emerged. This<br />

was led in the UK by Sinclair, with fierce<br />

competition from Commodore. At this<br />

time, the retail end was poorly<br />

organised, with console games being<br />

sold through a variety of outlets<br />

including electrical stores, photography<br />

shops and some of the high street<br />

chains. When the console market<br />

collapsed, these retailers pulled out. And<br />

as there were virtually no specialist<br />

games shops, publishers were forced to<br />

take out adverts in computer magazines<br />

and sell their software by mail order.<br />

The problem was one of classification.<br />

Were games merely toys, or published<br />

products like books and records, or did<br />

they rightly belong with consumer<br />

electronics alongside the computers on<br />

which they ran? There was no obvious<br />

answer.<br />

One certainty was that the trade was<br />

in disarray. The failure of the first<br />

consoles made retailers suspicious. The<br />

buyers for the larger high street chains<br />

like Woolworths and Boots were<br />

confused by the many different types of<br />

home computer. They did not know how<br />

to cope with suppliers who might<br />

produce a good game one month, then<br />

nothing but failures thereafter. They<br />

were afraid to commit to buying product<br />

unless they could be sure of returning<br />

unsold stock for a refund, but who<br />

knew how long the new games<br />

publishers would be in business?<br />

And how the hell do you sell a<br />

computer game anyway? A customer<br />

could flick through a book, listen to a<br />

record, play with a toy. Games were<br />

slow to load and needed some<br />

understanding which sales staff usually<br />

lacked. It seemed crazy to stick a tape<br />

into a computer, wait five minutes for it<br />

to load and then watch the potential<br />

customer play with it for ten minutes<br />

before deciding not to buy. Retailers<br />

were unsurprisingly sceptical and<br />

reluctant to believe there was any<br />

money to be made.<br />

Distribution<br />

deals<br />

Mastertronic was started by men<br />

who understood distribution and<br />

marketing. They knew nothing about<br />

computer games and were proud to<br />

boast that they never played them.<br />

When programmers came in with<br />