shadows-streets-book

shadows-streets-book

shadows-streets-book

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

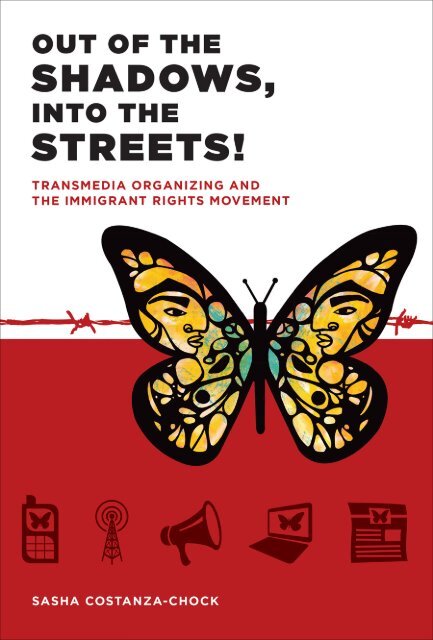

Out of the Shadows, Into the Streets!

Out of the Shadows, Into the Streets!Transmedia Organizing and the Immigrant Rights MovementSasha Costanza-ChockThe MIT PressCambridge, MassachusettsLondon, England

We are multitudes. No conocemos las fronteras.

ContentsForeword by Manuel CastellsAuthor ’ s Note xiiiAcknowledgments xvixIntroduction: ¡ Escucha! ¡ Escucha! ¡ Estamos en la Lucha! 11 A Day Without an Immigrant: Social Movements and the MediaEcology 202 Walkout Warriors: Transmedia Organizing 463 “ MacArthur Park Melee ”: From Spokespeople to Amplifiers 684 APPO-LA: Translocal Media Practices 865 Worker Centers, Popular Education, and Critical Digital MediaLiteracy 1026 Out of the Closets, Out of the Shadows, and Into the Streets:Pathways to Participation in DREAM Activist Networks 1287 Define American, The Dream is Now, and FWD.us: Professionalizationand Accountability in Transmedia Organizing 154Conclusions 179AppendixesAppendix A: Research Methodology 205Appendix B: Interviewees 215Appendix C: Interview Guide 217Appendix D: Online Resources for Organizers 221Notes 223Index 257

ForewordManuel CastellsOver the last few years, a wave of social protests has rippled across theworld, and in its wake we have witnessed the profile of the social movementsof the information age. Yet, because of the novelty of their formsof mobilization and organization, an ideological debate is raging over theinterpretation of these movements. Since in most cases they challengetraditional forms of politics and organizations, the political establishment,the media establishment, and the academic establishment have forthe most part refused to acknowledge their significance, even afterupheavals as important as those represented by the so-called Arab Spring,the Icelandic democratic rebellion, the Spanish “ Indignant ” movement,the Israeli demonstrations of 2012, Occupy Wall Street, the Brazilianmobilizations of 2013, and the Taksim Square protests, which shook upthe entrenched Islamic government of Turkey. Indeed, between 2010 and2014, thousands of cities in more than one hundred countries have seensignificant occupations of public space as activists have challenged thedomination of political and financial elites over common citizens, who,according to the protesters, have been disenfranchised and alienated fromtheir democratic rights.A key issue in this often blurred debate is the role of communicationtechnologies in the formation, organization, and development of themovements. Throughout history, communication has been central to theexistence of social movements, which develop beyond the realm of institutionalizedchannels for the expression of popular demands. It is only bycommunicating with others that outraged people are able to recognizetheir collective power before those who control access to the institutions.Institutions are vertical, and social movements always start as horizontal

xForewordorganizations, even if over time they may evolve into vertical organizationsfor the sake of efficiency. (This evolution is seen by many in the movementsas the reproduction of the same power structures that they aim tooverthrow.)If communication is at the heart of social mobilization, and if holdingpower largely depends on the control of communication and information,it follows that the transformation of communication in a given societydeeply affects the structure and dynamics of social movements. This transformationis multidimensional: technological, organizational, institutional,spatial, cultural. We live in a network society in which people andorganizations set up their own networks according to their interests andvalues in all domains of the human experience, from sociability to politics,and from networked individualism to multimodal communities. In thetwenty-first century there has been a major shift from mass communication(characterized by the centralized, controlled distribution of messagesfrom one sender to many receivers and involving limited interactivity, asexemplified by television) to mass self-communication (characterized bymultimodality and interactivity of messages from many senders to manyreceivers through the self-selection of messages and interlocutors andthrough the self-retrieving, remixing, and sharing of content, as exemplifiedby the Internet, social media, and mobile networks). The appropriationof networked communication technologies by social movements hasempowered extraordinary social mobilizations, created communicativeautonomy vis- à -vis the mass media, business, and governments, and laidthe foundation for organizational and political autonomy. In a world of2.5 billion Internet users and almost 7 billion mobile phone subscribers, asignificant share of communication power has shifted from corporationsand state bureaucracies to civil society — a shift well established by research.However, we have only scant grounded analysis of the technological,organizational, and cultural specificity of new processes of social mobilizationand community networking. Too often, there is a na ï ve interpretationof these important phenomena that boils down to descriptive accounts ofthe use of the newest communication technologies or applications bysocial activists. Instead, a complex set of distinct developments is at work.It is simply silly (or ideologically biased) to deny or downplay the empiricalobservation of the crucial role of networking technologies in the dynamicsof networked social movements. On the other hand, it is equally silly to

Forewordxipretend that Twitter, Face<strong>book</strong>, or any other technology, for that matter,is the generative force behind the new social movements. (No observer,and certainly no activist, defends this latter position; it is a straw manerected by traditional intellectuals, mainly from the left, as a way to garnersupport for their belief in the role of “ the party ”— any party — in leading“ the masses, ” who are deemed unable to organize themselves.) Moreover,my observations of movements around the world reveal that the new socialmovements are networked in multiple ways, not only online but in theform of urban social networks, interpersonal networks, preexisting socialnetworks, and the networks that form and reform spontaneously in cyberspaceand in physical public space. This networking consists of a processof communication that leads to mobilization and is facilitated by organizationsemerging from the movement, rather than being imported from theestablished political system. However, to make progress in understandingthese movements, we need scholarly research that goes beyond the cloudof ideology and hype to examine with methodological reliability howcommunication works in such movements and to understand with precisionthe interaction between communication and social movements.From this perspective, the <strong>book</strong> you hold in your hands represents afundamental contribution to a rigorous characterization of the new avenuesof social change in societies around the world. The concept of transmediaorganizing that Sasha Costanza-Chock proposes integrates the variety ofmodes of communication that exist in the real media practices of socialmovements. From the activists ’ point of view, any communication modethat works is adopted, so that the Internet and mobile platforms are usedalongside and in interaction with paper leaflets, interpersonal face-to-facecommunication, bulletins and newspapers, graffiti, pirate radio, street art,public speeches and assemblies in the square. Everything is included inwhat Costanza-Chock calls the media ecology of the movement. This isthe reality of the new movements and the foundation of their communicativeautonomy, on which their very existence depends, particularly whenrepression inevitably falls on them.Costanza-Chock identified this novel interaction between the shiftingmedia ecology and social movements long before the Arab Spring uprisingsor the Occupy movement came to the attention of the mass media.He focused on a most significant social development, the movement forimmigrant rights that exploded across the United States in 2006, with its

xiiForewordepicenter in Los Angeles. He studied this movement between 2006 and2013, beginning with his participation in the Border Social Forum, wherethe new realities of immigration were debated. Through a commitment tomethods of participatory research, he partnered with organizers and activistsfrom the immigrant rights movement, and worked with them as codesignersand coinvestigators in a range of popular communication initiatives.This courageous strategy of engaged scholarship allowed him to see thespecific, sometimes contradictory effects of different communication processesin the dynamics of the movement. For example, he identified thecentrality of critical digital literacy in grassroots social mobilization. In aworld in which the fight for one ’ s rights can be shaped decisively by one ’ sability to use the new means of communication, it is crucial to equalizeaccess to the direct use of communication technologies by grassrootsactors. By developing digital literacy, the movement can raise consciousnessas well as find better uses for digital tools as they are adaptedto movement goals. Otherwise the inevitable professionalization oftransmedia organizers leads to the formation of a technical leadership thatdoes not necessarily coincide with the leadership emerging from thegrassroots.The close analysis of these and related processes presented in the pagesof this fascinating <strong>book</strong> is of utmost importance for understanding thenew, networked social movements of the Internet age, as well as the potentialof new communication technologies to broaden citizen participationin institutional decision making. In the midst of a widespread crisis oflegitimacy faced by governments around the world, understanding theseprocesses is crucial for activists, concerned citizens, open-minded officials,and scholars everywhere. This <strong>book</strong> engages us in a fascinating intellectualand political journey. It raises, and often solves, many of the questionsnow being asked about networked social movements. It is based on impeccablescholarship, in which the author ’ s commitment to the defense ofimmigrant rights does not impinge on the integrity of his observation andanalysis. This is social research as it best: when normative values are notdenied by a detached academic but are served by investigative imaginationand theoretical capacity, yielding an accurate assessment of the ways andmeans of the new world in the making.

Author ’ s NoteThe author will donate half of the royalties from the sale of this <strong>book</strong> tothe Mobile Voices project. Mobile Voices (VozMob) is “ a platform forimmigrant and/or low-wage workers in Los Angeles to create stories abouttheir lives and communities directly from cell phones. VozMob appropriatestechnology to create power in our communities and achieve greaterparticipation in the digital public sphere. ” More information can be foundat http://vozmob.net .

AcknowledgmentsThis <strong>book</strong> owes everything to those who struggle on a daily basis to buildbeloved community in the immigrant rights movement and beyond. First,gr á cias a Mar í a de Lourdes Gonz á lez Reyes, Manuel Manc í a, Adolfo Cisneros,Crisp í n Jimenez, Marcos and Diana, Alma Luz, Ranferi, and the PopularCommunication Team of VozMob.net. Your stories continue to travelaround the world, providing insight and inspiration to everyone theytouch. You are truly leyendo la realidad para escribir la historia . AmandaGarces, you taught me so much; it ’ s incredible to look back and see howfar we came together. Thanks also to the tireless efforts of Raul A ñ orve,Marlom Portillo, Neidi Dominguez, Brenda Aguilera, Natalie Arellano, LuisValent í n, Pedro Joel Espinosa, and the whole IDEPSCA extended family. Ifeel honored to have been able to spend time building community withyou. It ’ s been a true journey through difficult times, pero llena de amor,respeto , and also delicious food. Thank you for exploring participatoryresearch and design, together with Carmen Gonzales, Melissa Brough,Charlotte Lapsansky, Cara Wallis, Veronica Paredes, Ben Stokes, Fran ç oisBar, Troy Gabrielson, Mark Burdett, and Squiggy Rubio.Thanks are also due to Virginia, Cristina, Cruz, Miguel, Consuelo, andeveryone who participated in Radio Tijera , as well as to Marissa Nuncio,Delia Herrera, Luz Elena Henao, Kimi Lee, simmi gandi, and all the incrediblepast and present organizers at the Garment Worker Center. Danny Park,Eileen Ma, and Joyce Yang, thank you for hosting the CineBang! screeningsand for providing a welcoming space at Koreatown Immigrant WorkersAlliance. Odilia and Berta at the Frente Ind í gena de Organizaciones Binacionales,and Max Mariscal: I still think about the taste of tamales y atoleduring APPO-LA protests and screenings at the Mexican consulate.

AcknowledgmentsxviiI am thrilled to have found a home at MIT in the Department of ComparativeMedia Studies/Writing. My colleagues have been deeply supportive,especially T. L. Taylor and Jim Paradis, who have both been unerringguides, mentors, and advocates for an unconventional junior scholar.T. L. and Jim also provided detailed and very valuable feedback on themanuscript, as did Otto Santa Ana, Virginia Eubanks, Nancy Meza, ChrisSchweidler, and several anonymous readers from the MIT Press.CMS/W faculty and staff, including William Uricchio, Vivek Bald, FoxHarrell, Nick Montfort, Ian Condry, Heather Hendershot, Junot D í az,Helen Elaine Lee, Thomas Levenson, Kenneth Manning, Seth Mnookin,David Thorburn, Jing Wang, and Ed Schiappa, as well as Kurt Fendt, SarahWolozin, Scot Osterweil, Philip Tan, Andrew Whitacre, Susan Tresch Fienberg,Jill Janows, Mike Rapa, Becky Shepardson, Jessica Tatlock, PatsyBaudoin, Federico Casalegno, Jessica Dennis, Sarah Smith, Shannon Larkin,and Karinthia Louis, have created a welcoming space for deep discussionand debate around the questions that animate this <strong>book</strong>.It was a pleasure to work closely with Rogelio Alejandro Lopez, whoconducted a series of interviews with immigrant rights activists for thisproject and also for his own work. Rogelio ’ s master ’ s thesis, a comparativestudy of media practices in the farm workers movement and the immigrantyouth movement, shaped my thinking about transmedia organizing as anapproach that has been used throughout social movement history. I havealso greatly enjoyed discussing the dynamics of media, publicity, andhidden resistance with Sun Huan, the history of consensus process andprefigurative politics with Charlie De Tar, networked social movementswith Pablo Rey Maz ó n, and collaborative design with Aditi Mehta.Dan Schultz egged me on to keep pushing the limits; I still insist he ’ s adead ringer for Guy Fawkes. Joi Ito had me covered when there was blowback,and I can ’ t say more in public.Thanks also to the brilliant and hardworking crew at the Center forCivic Media, especially Ethan Zuckerman, whose tweets urged me acrossthe finish line, as well as Lorrie LeJeune, Rahul Bhargava, Ed Platt, BeckyHurwitz, and Andrew Whitacre. I am constantly amazed at the breadthand depth of knowledge across the Civic community. I have only onequestion for brilliant graduate students and fellows Chelsea Barabas,Willow Brugh, Denise Cheng, Heather Craig, Kate Darling, Rodrigo Davies,Ali Hashmi, Alexis Hope, Catherine d’Ignazio, Nick Grossman, Alexandre

xviiiAcknowledgmentsGoncalves, Erhardt Graeff, Nathan Matias, Chris Peterson, Molly Sauter,Sun Huan, Rogelio Alejandro Lopez, Matt Stempeck, Wang Yu, and JudeMwenda Ntabathia: What does the fox say?Bex Hurwitz, you ’ ve been an excellent partner in crime; it has been trulyfabulous to work with you to develop theory and practice around collaborativedesign. I ’ m looking forward to many RAD projects to come!Early stages of work on research that made its way into this <strong>book</strong> weresupported by research assistantships with Manuel Castells, Ernest J. Wilson,Fran ç ois Bar, Holly Willis, and Jonathan Aronson, as well as by grants fromthe HASTAC/MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Competition,the USC Graduate School Fellowship in Digital Scholarship, the SocialScience Research Council Large Collaborative Grants program, and anAnnenberg Center for Communication Graduate Fellowship. More recently,my research has been supported by John Bracken at the Knight Foundation,Archana Sahgal at the Open Society Foundations, and Luna Yasui atthe Ford Foundation ’ s Advancing LGBT Rights Initiative.Manuel Castells guided me during the earliest stages of this project, andcontinually urged me, with a twinkle in his eye, to struggle for liberationin the institutions, on the net, and in the <strong>streets</strong>. Ivan Tcherepnin taughtme how to listen to the universe, and first turned me on to the politicaleconomy of communication. Silke Roth introduced me to social movementstudies, Dorothy Kidd gave me hope that scholars could stay linkedto movements, and Dee Dee Halleck inspired me with handheld visions.Steve Anderson pushed me to develop a practice of scholarly multimedia.Larry Gross, mentor and friend since we first met at the University ofPennsylvania, encouraged me to take up the path of engaged scholarship.This <strong>book</strong> would not exist if it weren ’ t for him.My parents, Carol Chock, Paul Mazzarella, Peter Costanza, and BarbaraZimbel, always inspired me to dream of another possible world, and totake action to make it real. We have to make it happen, not least for mytiny niece, Colette Miele. Larissa, I love you; Grandpa Jack and GrandmaBrunni, I miss you.I could never have completed this <strong>book</strong> without the love, support, andsharp editorial eye of my partner, Chris Schweidler. Chris helped me shapethis <strong>book</strong> from its earliest incarnation onward. Thank you for helping mefinally push it out into the world! Among the boulder piles of Joshua Tree,the otherworldly red rock formations of Sedona, and the limitless skies of

AcknowledgmentsxixAbiqui ú , you have guided me toward a new understanding of love andliberation. I want to walk beside you always.As this <strong>book</strong> goes to press, President Obama has deported two millionpeople. The immigrant rights movement is mobilizing across the countryto demand an end to deportations and meaningful immigration policyreform. Yet the so-called comprehensive immigration reform bills thatCongress is debating begin with $46 billion for the deadly political theaterof border militarization: more walls, drones, and Border Patrol agents; moredeaths, detentions, and deportations. In the face of such cruel absurdity,I only hope that this <strong>book</strong> can contribute in some small way to the longstruggle for freedom of movement, social justice, and respect for the planeton which we all live and move, born sin patr ó n y sin fronteras . 1

Introduction: ¡ Escucha! ¡ Escucha! ¡ Estamos en la Lucha!“¡ Escucha! ¡ Escucha! ¡ Estamos en la lucha! ” (Listen! Listen! We are in thestruggle!) The sound of tens of thousands of voices chanting in unisonbooms and echoes down the canyon walls formed by office buildings,worn-down hotels, garment sweatshops, and recently renovated lofts alongBroadway in downtown Los Angeles. The date is May 1, 2006, and I ammarching as an ally along with more than a million people from workingclassimmigrant families, mostly Latin@. We are pouring into the <strong>streets</strong> atthe peak of a mobilization wave that began in March and swept rapidlyacross the United States, grew to massive proportions in major metropolitanareas such as Chicago, New York, L.A., Philadelphia, San Francisco, LasVegas, and Phoenix, and reached much smaller towns and cities in everystate. The trigger was the draconian Sensenbrenner bill, H.R. 4437. The billwould have criminalized more than 11 million undocumented people andthose who work with them, including teachers, health care workers, legaladvocates, and other service providers. 1 The movement ’ s demands quicklyexpanded beyond stopping the Sensenbrenner bill and grew to encompassan end to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids, a fairand just immigration reform, and, more broadly, respect, dignity, and therecognition that immigrants are human beings.Another chant begins to build: “¡ No somos cinco, no somos cien! ¡ Prensavendida, cuentenos bien! ” (We aren ’ t five, we aren ’ t one hundred! Sold-outpress, count us well!) While the Spanish-language media played a crucialrole in supporting the mobilizations, the unprecedented magnitude of themarches caught the English-language media by surprise. Major Englishlanguagenewspapers, television and radio networks, blogs, and onlinemedia outlets only belatedly acknowledged the sheer scale of the movement.Some, in particular right-wing talk radio and Fox News, used the

2 Introductionmarches as an opportunity to launch xenophobic attacks against immigrantworkers, filled with vitriolic language about “ swarms ” of “ illegalaliens, ” “ anchor babies, ” and “ diseased Mexicans. ” 2 A forest of dishes andantennae bristles from the backs of TV network satellite trucks that linethe <strong>streets</strong> near City Hall. As the crowd passes the Fox News truck, theconsigna (chant) changes again, becoming simple and direct: “¡ Mentirosos!¡ Mentirosos! ” (Liars! Liars!)Emerging from Broadway into the open area around City Hall, I feel apowerful emotional wave course through the air. As a committed socialjustice activist as well as an engaged scholar and media-maker, I ’ ve beento many protests before. Often, these are composed of the same relativelysmall group of familiar faces. The wave of historic mobilizations againstthe Iraq War in 2003 is the last time I can remember being surrounded byliterally hundreds of thousands of people, many of them marching in the<strong>streets</strong> for the first time in their lives, joined in a broad coalition by shareddemands. 3 “¡ Se ve, se siente, el Pueblo esta presente! ” (You can see it, you canfeel it, the people are here!) For decades, modern social movements haveaimed to capture mass media attention as a crucial component of theirefforts to transform society. 4 Those who marched over and over again forimmigrant rights during the spring of 2006 did so in large part to fight forincreased visibility and voice in the political process, and they explicitlydemanded that the English-language press accurately convey the movement’ s size, message, and power. Yet over the course of the last twentyyears, widespread changes in our communications system have deeplyaltered the relationship between social movements and the media. Followingthe Telecommunications Act of 1996, which eliminated national capson media ownership and allowed a single company to own multiple stationsin the same market, the broadcast industry was swept by a wave ofconsolidation. 5 Spanish-language radio and TV stations, once localized toindividual cities, built significant market share, attracted major corporateadvertisers, and were largely integrated into national and transnationalconglomerates. 6 This process delinked Spanish-language broadcasters fromlocal programming and advertisers while simultaneously constructing new,shared pan-Latin@ identities. 7In the 2006 mobilizations, Spanish-language print media, television,and radio stations provided extensive coverage, and also played a criticalrole in calling people to the <strong>streets</strong>. The massive demonstrations

Introduction 3underscored not only the power of the Latin@ working class but also thegrowing clout of commercial Spanish-language media inside the UnitedStates. 8 At the same time, the rise of widespread, if still unequal, access tothe Internet and to digital media literacy provided new spaces for socialmovement participants to document and circulate their own struggles. 9Movements, including the immigrant rights movement, have rapidlytaken to blogging, participatory journalism, and social media. 10 Someimmigrant rights activists, who recognize these changes while remainingwary of the exclusion of large segments of their communities from thedigital public sphere, struggle for expanded access to critical digital medialiteracy. They also strive to better integrate participatory media into dailymovement practices. Others, uncomfortable with the loss of messagecontrol, resist the opening of social movement communication to a greaterdiversity of voices. This <strong>book</strong>, based on seven years of experience withparticipatory research, design, and media-making within the immigrantrights movement, explores these transformations in depth.A Book Born on the BorderThis <strong>book</strong> was born on the southern side of an invisible line in the sandbetween Texas and Chihuahua. At the Border Social Forum in CiudadJu á rez, Mexico, between October 12 and 15, 2006, almost one thousandactivists, organizers, and researchers gathered for three days. We met tobuild a stronger transnational activist network against the militarizationof borders and for freedom of movement and immigrant rights. I traveledto the Border Social Forum to connect with immigrant rights organizerswho were enthusiastic about integrating digital media tools and skills intotheir work. Many were based in L.A., and after the forum was over, wefollowed up to meet and develop projects together. Over the next few yearsI worked with organizers from the Los Angeles Garment Worker Center,the Institute of Popular Education of Southern California, the IndigenousFront of Binational Organizations, the Koreatown Immigrant Workers Alliance,and other immigrant rights groups and networks. Together we developedworkshops, tools, and strategies to build the media capacity of theimmigrant rights movement in L.A.These movement-based media experiences provided the foundationfor my understanding of the core issues addressed in this <strong>book</strong>. Working

4 Introductionwith community organizers inspired me to undertake research that mighthelp movement participants, organizers, and scholars better understandthe shifting relationship between the media system and social movements.I participated in or led more than one hundred hands-on mediaworkshops using popular education and participatory design approaches,conducted forty formal semistructured interviews, took part in dozens ofactions and mobilizations, and assembled an archive of media producedby the movement. Some of the research that led to this <strong>book</strong> took placein partnership with community-based organizations (CBOs), some didnot. A full description of the methods I employed can be found in theappendixes to this <strong>book</strong>.In general, my work falls under the rubric of participatory research, aterm subsuming a set of methods that emphasize the development of communitiesof shared inquiry and transformative action. 11 In other words, Iconsider the groups and individuals I work with to be coresearchers andcodesigners, rather than simply subjects of research or test users. As anengaged scholar, media-maker, and technologist, I have used these methodsto work with youth organizers, the global justice movement, the Indymedianetwork, antiwar activists, media justice and communication rightsadvocates, LGBTQ and Two-Spirit communities, Occupy Wall Street, workercenters, and the immigrant rights movement, among others. In some casesI identify as a movement participant, in others as an ally. I ’ m a white,male-bodied, queer scholar/media-maker/activist with U.S. citizenshipwho grew up in Ithaca, New York. In my teen years I lived in Puebla,Mexico, during the Zapatista uprising against NAFTA (the North AmericanFree Trade Agreement) and neoliberalism. I went to Harvard as an undergraduate,organized raves and electronic arts events with the ToneburstCollective, became involved in youth organizing in the Boston area, gotconnected to the global justice movement through the Indymedia network,produced movement films, and took my first job as a community artsworker in San Juan, Puerto Rico. I went to graduate school at the Universityof Pennsylvania, then focused on media policy advocacy for several yearswith Free Press. I then moved to L.A. to pursue a doctorate at the AnnenbergSchool for Communication & Journalism at the University of SouthernCalifornia and became deeply involved in the immigrant rightsmovement. I ’ m now assistant professor of civic media in the ComparativeMedia Studies/Writing Department at MIT. I work to leverage my race,

Introduction 5class, gender, and educational privilege to amplify the voices of communitiesthat have been systematically excluded from the public sphere. To thatend, I conduct research, write, teach, organize software developmentteams, and produce media in partnership with CBOs and movementgroups. My deepest and most long-lasting community engagement is asan ally of low-wage immigrant workers, especially those from Latin Americaand the Spanish-speaking Caribbean.I wrote this <strong>book</strong> because I believe that the immigrant rights movementhas a great deal to teach us all. Both scholars and activists recognize thatmedia and communications have become increasingly central to socialmovement formation and activity. 12 However, both scholarship and practicein this field suffer from at least three basic shortcomings. First, in thepast, most studies of social movements focused exclusively on the massmedia as the arena of public discourse. The ability of a social movementto change the public conversation was often measured by looking at articlesin elite newspapers or by counting sound bites in broadcast channels. 13Second, as movements became increasingly more visible online, a growingspotlight on the latest and greatest communication technologies began toobscure the reality of everyday communication practices. 14 On the ground,social movement media-making tends to be cross-platform, participatory,and linked to action. 15 In other words, as I note throughout this <strong>book</strong>,social movements engage in what I call transmedia organizing . Third, therise of the Internet as a key space for social movement activity cannot befully theorized without sustained attention to ongoing digital inequality. 16Understanding digital inequality means focusing on critical digital medialiteracy, in addition to basic questions of access to communication toolsand connectivity. 17 This <strong>book</strong> addresses these shortcomings by looking atthe broader media ecology rather than focusing exclusively on one or ahandful of platforms, by exploring daily movement media practices withina framework of transmedia organizing, and by confronting the challengesof digital inequality in the context of the immigrant rights movement. Myaim is to help us better understand how social movement actors engagein transmedia organizing as they seek to strengthen movement identity,win political and economic victories, and transform consciousness. Themain site of research is L.A., although I also incorporate examples fromBoston and elsewhere in the country, and the focus is the contemporaryimmigrant rights movement from 2006 to 2013.

6 IntroductionThe Revolution Will Be Tweeted, but Tweets Alone Do Not theRevolution MakeIn 2010, writing against the idea that specific media technologies automaticallyproduce movement outcomes, Malcolm Gladwell argued in awidely debated article that social media fail to produce the strong tiesand vertical organizational forms that he considered crucial to the successof the civil rights movement. 18 Gladwell did provide useful pushbackagainst technological determinism, and he reminded us that the keyforce in social movements has always been strong personal connections.However, he failed to acknowledge that social media are often used toextend and maintain existing face-to-face relationships, including the“ strong ties ” he values so much, over time and space. There ’ s actuallyno contradiction between the position that strong personal relationshipsare the key to social movements and the observation that social mediaare now important tools for movement activity. More problematic isGladwell ’ s conflation of strong ties with vertical organizational structure,which led him to argue that powerful social movements require a strong,military-style hierarchy. The idea that only vertically structured movementsare effective is both dangerous and wrong. It ignores the theory,practices, processes, and tools of social transformation that have emergedfrom the last fifty years (at least) of horizontalist organizing and theanti-authoritarian left. Feminists, ecologists, queer organizers, indigenousactivists, and anarchists of various stripes have long rejected top-downinstitutional structures and patriarchal and hierarchical styles of organizing.The turn toward power-sharing, consensus process, horizontalism,and networked movement forms has certainly been aided and enabledby networked information and communication technologies (ICTs).However, there is a much deeper history that underlies this shift. Horizontalism(or horizontalidad in the Latin American context, as describedso beautifully in Marina Sitrin ’ s <strong>book</strong> of the same name) 19 surged inpopularity from the late 1960s through the 1970s, spread by way ofunderground cultural scenes during the resurgence of the right in the1980s, and burst onto the forefront of globalized social movement activityin the mid-1990s with the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, Mexico. Ittook off again following the 1999 World Trade Organization protests,dubbed the “ Battle of Seattle, ” when horizontally organized, networked

Introduction 7affinity groups (consisting mostly of people who had been friends for along time beforehand) shut down the WTO ’ s Ministerial Conference andcatapulted the global justice movement into high visibility. 20 This mobilizationwas also the birthplace of Indymedia, a ragtag band of mediaactivists who scooped the major news networks from inside the cloudsof tear gas with cheap handheld cameras and an open publishing newssite built with Australian free software. 21 Coders from the Indymedianetwork went on to play key roles in the development of many widelyadopted social media platforms, including Twitter. 22By 2010, even as Gladwell was repeating the tired claim that we don ’ tsee movements like we used to because everyone is too busy with clicktivism,horizontalist movements were laying the foundation for an explosiveglobal cycle of struggles that linked decentralized mobilizations across theplanet in what Manuel Castells has called “ networks of outrage and hope. ” 23It ’ s true that most people in most times and places don ’ t become movementmilitants, yet “ anti-clicktivism ” looks downright silly in the face ofthe current social movement wave. The global protest cycle includes antiausterityriots in Greece; student protests for the right to education inLondon, Santiago de Chile, and Quebec; and the uprisings of the so-calledArab Spring that brought the fall of dictators in Tunisia and Egypt (and ledto civil war in Libya and Syria). It resonates from Tahrir Square to theSpanish Acampada del Sol, from Gezi Park in Istanbul to Occupy WallStreet and back again to #IdleNoMore. These movements are wildly disparatein their composition, goals, and outcomes; each is based in the specificityof local histories and conditions, but all share certain key components.First, they involve the reclaiming of public space by mass mobilizations.Second, significant groups within each movement reject the formal aspectsof representative democracy (political parties, governance based on periodicballots to elect political leaders, and so on) and enact prefigurativepolitics . 24 In other words, within the self-organized spaces controlled by themovement they attempt to directly build the types of social relationshipsthat they would like to see reflected in broader society. 25 Third, as describedby Paolo Gerbaudo, all are characterized by their ability to maintain apresence in both tweets and the <strong>streets</strong>: these movements are based on thephysical occupation of key urban locations, while they simultaneouslycapture the imagination of networked publics through extended visibilityacross social media sites. 26

8 IntroductionThis cycle of struggles is also linked to a renewal of intense popular andscholarly debates about the relationship between social media and socialmovements. Each day brings a broader diffusion of digital technologies,and each day seems also to bring a rush to attribute the latest popularprotest to the tools used by the protesters. Iran is the “ Twitter Revolution,” 27 the Arab Spring is “ powered by Face<strong>book</strong>, ” 28 and Occupy WallStreet is “ driven by iPads and iPhones. ” 29 However, every activist and organizerI interviewed for this <strong>book</strong> repeated some version of the idea that“ social media should enhance your on-the-ground organizing, not be youronly organizing space. ” 30 Digital media technologies cannot somehow besprinkled on social movements to produce new, improved mobilizations.On this point, Gladwell had it half right. Further complicating the debate,savvy activists, as well as critical scholars such as Siva Vaidhyanathan, alsonote the transition of the net from a relatively autonomous communicationspace to one dominated by the rise of corporate social media platforms,online versions of traditional media firms, and search and advertisingcompanies (Google). 31 The noted Internet skeptic Evgeny Morozov pointsout that movement participants face increased surveillance when they taketheir activities online; he has turned attacking social media boosterism intoa cottage industry by mixing valuable critiques of net-centric thinking withflashy rants against cyberutopian straw men. 32 My belief is that we canavoid both cyberutopianism and don ’ t-tweet-on-me reactions with a quitesimple strategy: learn from social movements about how they use variousICTs to communicate, organize, and mobilize, rather than start by researchingICTs and arguing about whether they are revolutionary. Indeed, carefulsocial movement scholars have done just that, and have begun to developa more nuanced understanding of the relationships between social mediaand social movements. For example, we know from the work of LanceBennett and others that social media are used by protesters to bridgediverse networks during episodes of contentious politics, 33 that coalitionsuse digital media to personalize collective action, and that digital mediaenable less rigid forms of affiliation while maintaining high levels ofengagement, a focused agenda, and high network strength. 34Much in this vein of scholarship resonates with the conclusions I drawhere about the ways that immigrant rights activists use social media. Atthe same time, I believe that an overemphasis on social media, and afailure to engage seriously with movement media across platforms, misses

Introduction 9the forest for the trees. 35 Social movement media practices don ’ t takeplace on digital platforms alone; they are made up of myriad “ smallmedia ” (to use Annabelle Sreberny ’ s term) that circulate online and off. 36Graffiti, flyers, and posters; newspapers and broadsheets; communityscreenings and public projections; pirate radio stations and street theater— these and many other forms of media-making abound withinvibrant social movements. Activists also constantly seek and sometimesgain access to much wider visibility through the mass media. Photographsand quotes in print newspapers, speaking slots on commercial FM radio,interviews on mainstream television news and talk shows — all these makeup part of the broader media ecology. The majority of people still receivemost of their information from the mass media, so social movements stillstruggle to make their voices and ideas heard in mass media outlets. It ismy contention that neither cyberutopians nor technopessimists (if eithertruly exist) have done a very good job of delving deeply into day-to-daymedia practices within social movements. This <strong>book</strong> attempts to do so,and to demonstrate that the revolution will be tweeted — but tweets alonedo not the revolution make.Si, Se Puede: Organized Immigrant Workers in L.A.It may at first seem strange, when discussing the transnational mobilizationwave that has inspired a new conversation about media and socialmovements, to focus on the immigrant rights movement in Los Angeles.Yet L.A. has long been a key location for new models of social movementorganizing, on the one hand, and the globalization of the media system,on the other. For example, innovative worker organizing models havecontinued to emerge from L.A. even as labor unions across the UnitedStates have steadily lost momentum from the 1950s on. In part, this isbecause Los Angeles is one of the few U.S. cities that still retains a substantialmanufacturing industry. L.A. has also been the site of importantadvances in service-sector organizing. The city is a global hub for immigrationand draws many migrants with strong organizing backgrounds,including political refugees who were organizers or revolutionaries intheir countries of origin. In their new home, migrants from diverse socialmovement traditions meet, and so the city has become a crucible of multiracial,cross-cultural organizing. 37

10 IntroductionThis was not always the case. Historically, organized labor in L.A. atworst attacked, and at best ignored, new immigrant workers. In additionto low-wage service work, L.A. has the largest remaining concentration ofmanufacturing in the country, 38 and labor unions for decades focusedon waging a losing battle to maintain their existing base in the privatemanufacturing sector. After the Taft-Hartley Act (1947) hamstrung the U.S.labor movement, regulated strike actions, banned the general strike, andoutlawed cross-sector solidarity, the old-guard labor unions, especially theAFL-CIO, shifted vast resources away from organizing new workers into alosing strategy of pouring money into Democratic Party electoral campaigns.They hoped to win new federal labor protections, or simply tomaintain existing ones. 39 The largest labor unions continued to follow thisstrategy, even as the Democratic Party moved ever closer to the businessclass and repeatedly sold out the labor movement. Union membershipsteadily declined as free trade became the consensus mantra among bothmajor political parties, and former union jobs in sector after sector wereoutsourced to cheaper production sites overseas. 40Yet starting in the 1990s, L.A. emerged as one of the key centers for thedevelopment of new models of labor organizing. This dynamic operatedin parallel with the rise of new leadership inside the massive service-sectorunions, including the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), theHotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union (HERE),and the Union of Needletrades, Industrial, and Textile Employees (UNITE).These unions, along with the United Farm Workers, United Food and CommercialWorkers, and the Laborers ’ International Union of North America,began to shift resources toward organizing new workers, including recentimmigrants. 41 In 2005 they launched the Change to Win Federation, anumbrella campaign designed to link service-sector workers across thecountry. As a result of organizing new immigrant workers instead ofattempting to exclude them, these unions saw a rise in new membership,rather than the steady decline suffered by manufacturing sector unions.SEIU, for example, grew from 625,000 members in 1980 to over 2.2 millionin 2013. L.A. ’ s SEIU Local 1877 pioneered a string of internationally visiblecampaigns with low-wage immigrant workers in the lead, such as Justicefor Janitors, Airport Workers United, and Stand for Security. 42 However,none of the major labor unions, including SEIU and UNITE-HERE, havebeen willing to devote significant resources to organizing garment workers

Introduction 11or day laborers in L.A. They have long seen these workers as unorganizable,based on their assumptions about the high proportion of undocumentedworkers in these sectors. 43Despite the assumption that undocumented workers are unorganizablebecause they fear deportation, a number of scholars have demonstratedthat there is no simple relationship between workers ’ immigration statusand their propensity to unionize. 44 Hector Delgado analyzed unionizationcampaigns in the light manufacturing sector in L.A. and found that otherfactors, such as state and federal labor law, organizing strategy, theresources committed to the effort by labor unions, and the resourcesdeployed by the employer to fight unionization, were all far greater determinantsof unionization outcomes than workers ’ immigration status. 45 Infact, in many cases new immigrant workers come from places with muchhigher rates of unionization, more militant unions, and stronger socialmovement cultures than their new home; they may arrive with a moreconcrete class identity than U.S.-born workers, and in some cases maythemselves have been trained as organizers. To take one example, daylaborers in L.A. have historically been largely unorganized, but this situationhas begun to change in recent years. A quarter of day laborers nowparticipate in worker centers, and the number of worker centers isgrowing. Day laborers in L.A. were the first in the country to organizeworker centers, and the model has spread. By 2006 there were sixty-threeday laborer centers in cities across the United States, with an additionalfifteen CBOs working with the day laborer community. 46 CBOs in L.A.,including the Institute of Popular Education of Southern California(IDEPSCA) and the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles(CHIRLA), led the creation of the National Day Laborer OrganizingNetwork, which has now grown to include thirty-six member organizationsin cities across the country. 47Los Angeles has also been a site for innovative partnerships between theCatholic Church and labor, as well as for models of organizing that focusnot only on the workplace but also on building community more broadly.Faith-based organizing in L.A. is closely tied to the history of U.S. imperialadventures in Latin America. In the 1980s, many priests and laity whowere active in Central American popular movements against U.S.-backedmilitary dictatorships were forced to flee their countries of origin. Manycame to the United States and ended up in L.A., where they have continued

12 Introductionto organize their communities through the practice of liberation theology.48 Diverse histories have thus shaped the immigrant rights movementin L.A. as it has spread through community centers, worker centers, faithbasedcoalitions, multiethnic organizing alliances, and other innovativeforms of community organizing. During the last two decades, there hasalso been a shift away from “ turf war ” unionism and towards attempts toorganize entire sectors of the workforce at once, through networks ofunions, CBOs, churches, and universities. 49 L.A. ’ s racial, ethnic, and culturaldiversity has also generated innovative organizing forms. Aside fromthe labor movement and the churches, the immigrant rights movementincludes a vast and diverse array of less visible but highly active CBOs,student groups, cultural activists, media- and filmmakers, progressive lawfirms, radical scholars, musicians, punks, and anarchists, hip-hop artists,mural painters and graffiti writers, indigenous rights activists, queer collectives,and many others. The rich history of intersecting social movementsin L.A. — described by Laura Pulido as “ Black, Brown, Yellow, andLeft ”— has been extensively documented by many scholars and activists,and I encourage interested readers to explore that literature further ontheir own. 50At the same time, L.A. has long been a key site for the development andgrowth of the globalized cultural industries. Hollywood remains both thesymbolic and material center of global film production, despite trendstoward transnational coproduction networks, recentralization in cheapersites of production, and the rise of studios in New York, Toronto, and NewZealand, not to mention the steady growth of competitive regional filmexport industries in India (Bollywood), Nigeria (Nollywood), South Korea,and China. 51 Besides film, native media industries in L.A. include television,music, games, and, most recently, transmedia production companies.The city looms large in wave after wave of transformation in the broadermedia ecology. L.A. occupies a unique location in the global imagination:it is a city of dreams, image making, and myths. It symbolizes both thepromise and the deception of the American project, and it remains animportant site of popular resistance, radical imagination, and concretemovement-building work.The immigrant rights movement in L.A. is thus a rich, complex, multilayeredworld. It lies at the fertile confluence of the cross-platform powerof the globalized cultural industries and the innovative, intersectional

14 IntroductionChapter 2, “ Walkout Warriors: Transmedia Organizing, ” is an in-depthstudy of the media practices of the college, high school, and middle schoolstudents who organized the largest wave of student walkouts since theChican@ Blowouts in the 1970s. They did this through a combination offace-to-face organizing, especially by way of long-established studentgroups, and the abundant use of new media tools and platforms, in particulartext messaging and MySpace. They also leveraged culturally relevantprotest tactics. School walkouts, already part of what social movementscholars call the “ repertoire of contention ” 52 of Chican@ student activism,were made especially salient by the production process of the HBO filmWalkout, released in 2006 . Produced by Edward James Olmos and MoctezumaEsparza (one of the organizers of the dramatized events), the filmused East L.A. high schools as sets and hundreds of students as extras. LikeSpanish-language broadcasters and social network sites, as discussed in thefirst chapter, the film mediated and promoted specific movement tactics.At the same time, walkout participants produced and circulated their ownmedia across multiple platforms, linked media directly to action, and didso in ways accountable to the social base of their movement. In otherwords, they took part in what I have termed transmedia organizing. Theterm builds on media scholar Henry Jenkins ’ s concept of transmedia storytelling,53 as well as on transmedia producer Lina Srivastava ’ s transmediaactivism framework, 54 while shifting the emphasis from professional mediaproducers to grassroots, everyday social movement media practices. I arguethat transmedia organizing is the key emergent social movement mediapractice in a converged media ecology shaped by the broader politicaleconomy of communication. 55Chapter 3, “‘ MacArthur Park Melee ’: From Spokespeople to Amplifiers, ”explores the transition of allied media-makers from spokespeople for socialmovements to aggregators and amplifiers of diverse voices from the movementbase. On May Day of 2007, the Los Angeles Police Department(LAPD) brutally attacked a peaceful crowd of thousands of immigrantrights marchers in L.A. ’ s MacArthur Park. Using batons, rubber bullets, andmotorcycles, nearly 450 officers in full riot gear injured dozens of peopleand sent several to the hospital, including reporters from Fox News, Telemundo,KPCC, KPFK, and L.A. Indymedia. The police were later found bythe courts to be at fault for unnecessary violence against the protesters.LAPD Chief Bratton apologized, the commanding officer was demoted,

16 Introductionmedia literacy, tools, and skills than any other group in the United States.What is the immigrant rights movement doing to ensure that its socialbase gains access to digital media tools and skills? Many activists, organizers,and educators wrestle with this question. In chapter 5, “ Worker Centers,Popular Education, and Critical Digital Media Literacy, ” I describe howCBOs at the epicenter of the immigrant rights movement struggle tosupport their communities by setting up computer labs and organizingcourses in computing skills. Some go further and use popular educationmethods to link digital media literacy directly to movement building. Idiscuss the mobile media project VozMob and the community radio workshopRadio Tijera to illustrate the ways that immigrant rights organizersare creating popular education workshops that combine critical mediaanalysis, media-making, participatory design, cross-platform production,leadership development, and more. I argue that these organizers are developinga praxis of critical digital media literacy within the immigrant rightsmovement. They have a great deal to teach organizers in other social movements.Educators who are concerned about digital media and learningwould do well to learn from their example.Chapter 6, “ Out of the Closets, Out of the Shadows, and Into the Streets:Pathways to Participation in DREAM Activist Networks, ” follows the diversepaths people take as they become politicized, connect to others, and maketheir way into social movement worlds. In this chapter I focus on DREAMers:undocumented youth who were brought to the country as youngchildren and who are increasingly stepping to the forefront of the immigrantrights movement. The term comes from the proposed Development,Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act, which offers a streamlined pathto citizenship for youth brought to the United States by their parents.Among other pathways to participation, I find that making media oftenbuilds social movement identity; in many cases, media-making projectshave a long-term impact on activist ’ s lives. DREAM activists, often youngqueer people of color, have developed innovative transmedia tactics as theybattle anti-immigrant forces, the political establishment, and sometimesmainstream immigrant rights nonprofit organizations in their struggle tobe heard, to be taken seriously, and to win concrete policy victories at boththe state and federal levels.Chapter 7, “ Define American, the Dream is Now, and FWD.us: Professionalizationand Accountability in Transmedia Organizing, ” explores the

18 Introductionimmigrant workers now make up a growing proportion of new unionmembers and organizers, especially in the service-sector unions. They arealso increasingly active in the fight for immigration reform, as well as inother social struggles, and constitute a large and growing political forceboth in L.A. and nationwide.However, even as the Internet steadily gains importance as a communicationplatform, a workplace, a site of play, a location for political debate,a mobilization tool, and indeed as a necessity in all spheres of daily life,low-wage immigrant workers are largely excluded from the digital publicsphere. Many are not online, and less than a third have broadband accessin the home. While most do have access to basic mobile phones or featurephones with cameras, few have smartphones. Yet at the same time, theimmigrant rights movement is one of the most powerful social movementsin the United States today. During the last decade the movement hasrepeatedly produced major episodes of mobilization, blocked key legislativeattacks at both state and federal levels, forced the Republican Party toabandon the Sensenbrenner bill, compelled the Obama administration toimplement the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, won stateby-statevictories and fought hard against state-level defeats, and in 2013moved comprehensive immigration reform to the top of the nationalagenda. How? In this <strong>book</strong>, I explore this question, guided by insightsgained from my own participation as a movement ally, as well as frominterviews, workshops, media archives, and more.I wrote this <strong>book</strong> in part because I believe there are some big analyticalgaps in how we think about the relationship between social movementsand the media. I don ’ t believe it ’ s productive to try to prove or disprove acausal relationship between technology use and social movement outcomes.Rather than think of technology use as an independent variablethat can predict movement outcomes — a claim that may or may not betrue, and one that I ’ m not making and am not in a position to empiricallytest — I ’ m encouraging social movement and media scholars, as well asmovement participants, to stop treating the media as either primarily anenvironmental element, something external to the movement dynamic,or a dependent variable, something to be “ influenced ” by effective movementactions. Instead, I hope to demonstrate in depth the ways in whichmedia-making is actually part and parcel of movement building. I believethat this has always been true, but that it ’ s more obvious now because we

Introduction 19can see it unfolding online. Social movements have always engaged intransmedia organizing; organizers bring the battle to the arena of ideas byany media necessary.I hope this <strong>book</strong> can help us move past the current round of debatesabout social movements and social media. It is past time to challengenarrow conceptions of the movement-media relationship. Let ’ s replaceboth paeans to the revolutionary power of the latest digital platform andreductive denunciations of “ clicktivism ” with an appreciation of the richtexture of social movement media practices. Along the way, I hope thatthis <strong>book</strong> also may provide useful lessons for activists as they attempt tonavigate a rapidly changing media ecology while organizing to transformour world.

Figure 1.1May Day 2006: A Day Without an Immigrant.Source: Photo by Jonathan McIntosh, posted to Wikimedia.org at http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:May_Day_Immigration_March_LA03.jpg (licensed CC-BY-2.5).

1 A Day Without an Immigrant: Social Movements andthe Media EcologyThe image in figure 1.1 depicts the <strong>streets</strong> of downtown Los Angeles onMay 1, 2006. This scene was mirrored in cities across the country as millionsof new immigrants, their families, and their allies joined the largestprotest in U.S. history. 1 They left their homes, schools, and workplaces,gathered for rallies and mass marches, and took part in an economicboycott for immigrant rights. This chapter explores the May Day 2006mobilization, known as A Day Without an Immigrant, through the lens ofthe changing media ecology. 2Our media are in the midst of rapid transformation. On the one hand,mass media companies continue to consolidate, more and more journalistsare losing their jobs to corporate downsizing, and long-form, investigativejournalism is steadily being replaced by less costly recycled press releasesand entertainment news. 3 Public broadcasters remain one of the mosttrusted information sources, but their funding is under attack. As audiencesfragment across an infinite-channel universe, the agenda-setting power ofeven the largest media outlets wanes. On the other hand, regional consolidationhas produced new channels that speak from the former peripheries.For example, Latin American media firms now reach across the UnitedStates, and Spanish-language print and broadcast media draw larger audiencesand wield more influence than ever before. 4 At the same time, widespread(though still unequal) access to personal computers, broadbandInternet, and mobile telephony, as well as the mass adoption of socialmedia, have in some ways democratized the media ecology even as theyincrease our exposure to new forms of state and corporate surveillance.Social movements, which have always struggled to make theirvoices heard across all available platforms, are taking advantage of thesechanges. The immigrant rights movement in the United States faces mostly

22 Chapter 1indifferent, occasionally hostile, English-language mass media. The movementalso enjoys growing support from Spanish-language print newspapersand broadcasters. At the same time, commercial Spanish-language massmedia constrain immigrant rights discourse within the framework of neoliberalcitizenship. Community media outlets that serve new immigrantcommunities, such as local newspapers and radio stations, continue toprovide important platforms for immigrant rights activists. Increasingly,social movement groups also self-document: they engage their base inparticipatory media-making, and they circulate news, information, andculture across many platforms, especially through social media. In thespring of 2006, the immigrant rights movement was able to take advantageof opportunities in the changing media ecology to help challenge anddefeat an anti-immigrant bill in the U.S. Congress.Immigration policy, border militarization, domestic surveillance, raids,detentions, and deportations are all key tools of control over low-wageimmigrant workers in the United States. These tools are not new. Theyhave been developed over the course of more than 130 years, at least sincethe Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first major law to restrict immigration.This law, the culmination of decades of organizing by white supremacists,barred Chinese laborers from entering the United States and fromnaturalization. 5 Immigration policy, surveillance, detention, and deportationhave long been used to target “ undesirable ” (especially brown, yellow,black, left, and/or queer) immigrants 6 and thereby to maintain whiteness,heteropatriarchy (the dominance of heterosexual males in society), 7 andcapitalism. 8 The past decade, however, has been particularly dark for manyimmigrant communities. After the September 11, 2001, attacks, the consolidationof Immigration and Naturalization Services into the Departmentof Homeland Security was followed by the “ special registration ” program,then by a new wave of detentions, deportations, and “ rendering ” of “ suspectedterrorists ” to Guant á namo and to a network of secret militaryprisons for indefinite incarceration and torture without trial. 9 In 2006,Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) increased the number ofbeds for detainees to 27,500, opened a new 500-bed detention center forfamilies with children in Williamson County, Texas, and set a new agencyrecord of 187,513 “ alien removals. ” 10 By the spring of that year, it hadbecome politically feasible for the Republican-controlled House of Representativesto pass H.R. 4437, better known as the Sensenbrenner bill.

A Day Without an Immigrant 23Sensenbrenner would have criminalized 11 million unauthorized immigrantsby making lack of documentation a felony rather than a civil infraction.It would also have criminalized the act of providing shelter or aid toan undocumented person, thus making felons of millions of undocumentedfolks, their families and friends, and service workers, includingclergy, social service workers, health care providers, and educators. 11 TheRepublican Party used the bill and the debates it provoked to play on whiteracial fears in an attempt to gain political support from the nativist elementof their base. The Sensenbrenner bill abandoned market logic: a CatoInstitute analysis found that reducing the number of low-wage immigrantworkers by even a third would cost the U.S. economy about $80 billion.By contrast, the same study found that legalizing undocumented workerswould grow the U.S. economy by more than 1 percent of GDP, or $180billion. 12The response to the Sensenbrenner bill was the largest wave of massmobilizations in U.S. history. A rally led by the National Capital ImmigrationCoalition on March 7 brought 30,000 protesters to Washington, D.C.;soon after, on March 10, 100,000 attended a protest in downtown Chicago. 13Yet these events were only the tip of the iceberg. March, April, and May2006 saw mass marches in every U.S. metropolis, as well as in countlesssmaller cities and towns. In the run-up to May Day (May 1), a date stillcelebrated in most of the world as International Workers ’ Day, immigrantrights organizers called for a widespread boycott of shopping and work.The economic boycott, also a de facto general strike, was promoted as “ ADay Without an Immigrant, ” a direct reference to the 2004 film A DayWithout a Mexican . The film (a mockumentary by director Sergio Arau)portrays the fallout when immigrant Latin@s disappear from California enmasse, leaving nonimmigrants to do the difficult agricultural, manufacturing,service-sector, and household work that is largely invisible, but providesthe foundations for the rest of the economy. Participation in the DayWithout an Immigrant mobilizations was immense: half a million peopletook to the <strong>streets</strong> in Chicago, a million in Los Angeles, and hundreds ofthousands more in New York, Houston, San Diego, Miami, Atlanta, andother cities across the country. In many places, these marches were thelargest on record. 14What produced such a powerful wave of mobilization? The surgingstrength of the immigrant rights movement was built through the hard

24 Chapter 1work of hundreds of organizations, including grassroots groups, nonprofitorganizations, regional and national networks, and policy-focused Beltwaygroups. 15 At the same time, the rapidly changing media ecology providedcrucial opportunities for the movement to grow, attract new participants,reach an unprecedented size, and achieve significant mobilization, cultural,and policy outcomes. 16A Day Without an ImmigrantEnglish-language TV news channels have long played important roles inthe information war that swirls around human migration. However, in thespring of 2006, all major English-language media outlets completely failedto anticipate the strength of the movement and the scale of the mobilizations.By contrast, Spanish-language commercial broadcasters, includingthe nationally syndicated networks Telemundo and Univision, providedconstant coverage of the movement. Spanish-language newspapers, TV,and radio stations not only covered the protests but also played a significantrole in mobilizing people to participate. 17 This was widely reportedon in the English-language press after the fact. 18 Indeed, by most accounts,commercial Spanish-language radio was the key to the massive turnout incity after city. In L.A., Spanish-language radio personalities, or locutores ,momentarily put competition aside in order to present a unified message:they urged the city ’ s Latin@ population to take to the <strong>streets</strong> against theSensenbrenner bill. Media scholar Carmen Gonzalez describes a historicmeeting and press conference held by the locutores :On March 20th all of the popular Spanish-language radio personalities gathered at theLos Angeles City Hall to demonstrate their support for the rally and committed todoing everything possible to encourage their listeners to attend. Those in attendanceincluded: Eduardo Sotelo “ El Piol í n ” & Marcela Luevanos from KSCA “ La Nueva ”101.9FM; Ricardo Sanchez “ El Mandril ” and Pepe Garza from KBUE “ La Que Buena ”105.5FM; Omar Velasco from KLVE “ K-Love ” 107.5FM; Renan Almendarez Coello “ ElCucuy ” & Mayra Berenice from 97.7 “ La Raza ”; Humberto Luna from “ La Ranchera ”930AM; Colo Barrera and Nestor “ Pato ” Rocha from KSEE “ Super Estrella ” 107.1FM. 19These and other locutores across the country had a combined listener basein the millions. They ran a series of collaborative broadcasts during whichthey joined each other physically in studios and called in to one another ’ sshows. They focused steadily on the dangers of H.R. 4437, the need to taketo the <strong>streets</strong>, and the demand for just and comprehensive immigration

26 Chapter 1While the mass marches were largely organized through broadcast media,especially Spanish-language talk radio, text messages and social networkingsites (SNS) were the key media platforms for the student walkouts thatswept Los Angeles and some other cities during the same time period. 23 Asthe anti-Sensenbrenner mobilizations provided fuel for the fires of the(mostly Anglo, middle-class) blogosphere, walkout organizers enthusiasticallyturned to MySpace and YouTube to circulate information, report ontheir own actions, and urge others to join the movement. At the same time,text messaging (also called SMS, or short messaging service) was used as atool for real-time tactical communication. Student organizers I interviewedmade it clear that both text messaging and MySpace played important butnot decisive roles in the walkouts. 24 Pre-existing networks of students organizedthe walkouts for weeks beforehand by preparing flyers, meeting withstudent organizations, doing the legwork, and spreading the word. Somesaid that text messages and posts to MySpace served not to “ organize ” thewalkouts but to provide real-time confirmation that actions were reallytaking place. For example, one student activist told me about checking herMySpace page during a break between classes. She said that it was when shesaw a photograph posted to her wall from a walkout at another school thatshe realized her own school ’ s walkout was “ really going to happen. ” 25 Thatgave her the courage to gather a group of students, whom she already knewthrough face-to-face organizing, and convince them that it was time to takeaction. 26 Another high school student activist explained:It was organized, there was flyers, there was also people on the Internet, on chat linesand MySpace, people were sending flyers also. So that ’ s also one of the ways that itwas organized. The thing is that students just wanted their voice to be heard. Sincethey can ’ t vote, they ’ re at least trying to affect the vote of others, by saying theiropinion towards H.R. 4437 affecting their schools and their parents or their family. 27This student activist, like many of those I worked with and interviewed,emphasized the pervasive and cross-platform nature of movementmedia practices during the spring of 2006. Staff at community-basedorganizations repeatedly described radio as the most important mediaplatform for mobilizing the immigrant worker base. By contrast, studentactivists often mentioned SNS (specifically MySpace, the most popularSNS at the time) as a key communication tool during the walkouts.A few also mentioned email (especially mailing lists) and blogs, butmost emphasized that organizing took place through a combination of

A Day Without an Immigrant 27face-to-face communication with friends, family, and organized studentgroups, printed flyers, text messages, and MySpace. I discuss the walkoutsin more detail in chapter 2; for now it is enough to say that media organizingduring the walkouts involved pervasive all-channel messaging, asyoung people urged one another to take action to defeat Sensenbrennerand stand up for their rights.Analyzing A Day Without an Immigrant and the student walkouts side byside, we can see the contours of the overall media ecology for the immigrantrights movement in 2006. Although ignored, if not attacked, by Englishlanguagemass media and bloggers, the movement against the Sensenbrennerbill was able to grow rapidly by leveraging other platforms. CommercialSpanish-language broadcast media reported on the movement in detail, and,in the case of Spanish-language radio hosts, actively participated in mobilizingmillions. At the same time, middle school, high school, and universitystudents combined face-to-face organizing and DIY media-making, andused commercial SNS and mobile phones to circulate real-time informationabout the movement, coordinate actions, and develop new forms of symbolicprotest. As these practices spread rapidly from city to city, the mobilizationscontinued to grow in scope and intensity. The vast scale of the movementwas reflected in the slogan, “ The sleeping giant is now awake! ” The movement’ s power briefly caught the opposition off guard, and the Sensenbrennerbill died, crushed by the gigante (giant) of popular mobilization.Movements and the Media Ecology: Looking across PlatformsWe ’ ve seen, briefly, how the changing media ecology presented opportunitiesfor the immigrant rights movement during the 2006 mass mobilizationwave. Next, we will explore how immigrant rights activists engage acrossall available media platforms, including English-language mass media,Spanish-language mass media, community media (especially radio), andsocial media. The immigrant rights movement can teach us a great dealabout how social movement media strategy today extends across platforms,despite the recent turn in the press, the academy, and activist circlestoward a nearly exclusive emphasis on the latest and greatest social mediaplatforms. At the same time, cross-platform analysis helps us understandwhat is really new in social movement media practices. For example, inthe past, the main mechanism for advancing movement visibility, frames,

28 Chapter 1and ideas was through individual spokespeople who represented themovement in interviews with print or broadcast journalists working forEnglish-language mass media. This mechanism is now undergoing radicaltransformation. For the immigrant rights movement, increasingly powerfulSpanish-language radio and TV networks provide important openings.At the same time, social media have gained ground as a crucial space forthe circulation of movement voices, as the tools and skills of media creationspread more broadly among the population. I begin, however, bylooking at the tense relationship between the movement and what activistscall “ mainstream media. ”English-Language Mass MediaMany immigrant rights organizers express frustration with “ mainstreammedia. ” By mainstream media they usually mean English-language newspapersand TV networks, especially those with national reach. Their feelingsabout unfair coverage are supported by the scholarly literature. Forexample, a recent meta-analysis of peer-reviewed studies of immigrationframing in English-language mass media (by Larsen and colleagues) foundthat when immigrants are covered at all, they are usually talked about interms that portray them as dangerous, threatening, “ out of control, ” or“ contaminated. ” 28 Despite some recent gains, such as the Drop the I-Wordcampaign that, in 2013, convinced both the Associated Press and the LosAngeles Times to stop using the terms “ illegal immigrant ” and “ illegalalien, ” professional journalists generally continue to use dehumanizinglanguage to refer to immigrants who lack proper documentation. 29 Indeed,a 2013 study by the Pew Research Center found that, despite some recentshifts toward the use of “ undocumented immigrant ” and away from“ illegal alien, ” “ illegal immigrant ” remains by far the most common termused in the English-language press. 30Nonetheless, by focusing on lifting up the voices of immigrants and portrayingthem as full human beings, the immigrant rights movement hassometimes been able to shift public discourse. For example, immediatelyafter the 2006 mobilizations, a research group led by Otto Santa Ana at UCLAconducted a critical discourse analysis of mainstream newspaper reportingon immigration policy, immigration, and immigrants. The group gatheredone hundred key newspaper articles from two time periods: first, immediatelyafter the May 2006 mobilizations, and second, in October 2006, after

A Day Without an Immigrant 29public attention had moved on. The authors found and categorized approximatelytwo thousand conceptual metaphors used to refer to immigrantsin English-language newspaper coverage during these time periods. Theydetermined that the discursive core of the immigration debate is about thenature of unauthorized immigrants: on one side, there is a narrative of theimmigrant as a criminal or animal, and on the other there is a narrative ofthe immigrant as a worker or a human being. Through a quantitative analysisof metaphor frequency, they found that, during coverage of the massmobilizations in the spring of 2006, newspapers did shift toward a balancebetween the use of humanizing (43 percent) and dehumanizing (57 percent)metaphors about immigrants. However, by October, after the mobilizationshad faded from public memory, newspapers switched back to employ dehumanizingmetaphors more than twice as frequently as humanizing ones (67percent of the time). 31 The discursive battle in English-language mass mediais thus a long, slow, and painful process for immigrant rights organizers andfor the communities they work with.Many organizers say they occasionally do manage to gain coverage inmainstream media, but only in exceptional circumstances. One, who workswith indigenous migrant communities, put it this way: “ It ’ s rare that weget the attention of the mainstream media unless there ’ s blood or something.Then they ’ ll come to us if it ’ s related to indigenous people. ” 32 Shefeels that she is called on to speak as an expert about indigenous immigrants,but only in order to add color to negative stories about her community.She also mentioned that the difficulty seemed specific to L.A., andto the Los Angeles Times in particular; she feels that local partners of herorganization in some other Californian cities have more luck with mainstreammedia. Many also express frustration that movement victories inparticular are almost never covered. They find it especially galling that themass media flock to cover the activities of tiny anti-immigrant groupswhile ignoring the hard day-to-day work done by thousands of immigrantrights advocates. One said, “ I feel like a lot of the great work that ’ s goingon with organizations, say day laborers won a huge settlement or claim,you ’ re not going to hear about it in the mass media. What we do hearabout immigrant rights is anti-immigrant rights and anti-immigrantsentiment. That ’ s pretty [much] across the board, that ’ s how it ’ s presented.” 33 A few feel that anti-immigrant rights activists get more coveragebecause they are more savvy about pitching their actions to journalists,and that the immigrant rights movement could do a much better job