American Record Guide - Emmanuel Siffert - conductor

American Record Guide - Emmanuel Siffert - conductor

American Record Guide - Emmanuel Siffert - conductor

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

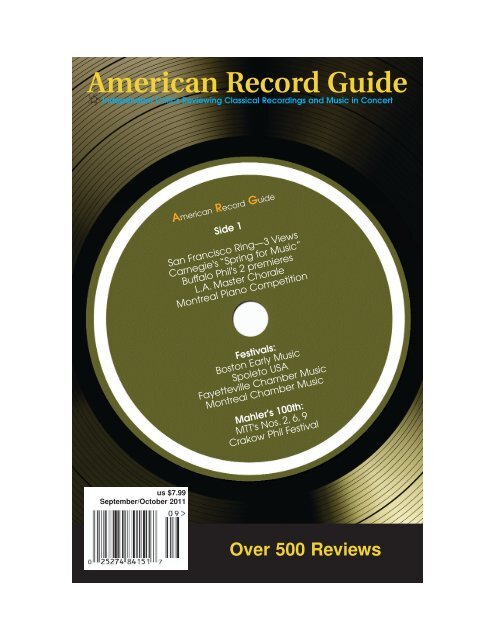

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong><br />

Independent Critics Reviewing Classical <strong>Record</strong>ings and Music in Concert<br />

&<br />

us $7.99<br />

September/October 2011<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong><br />

Side 1<br />

San Francisco Ring—3 Views<br />

Carnegie's “Spring for Music”<br />

Buffalo Phil's 2 premieres<br />

L.A. Master Chorale<br />

Montreal Piano Competition<br />

Festivals:<br />

Boston Early Music<br />

Spoleto USA<br />

Fayetteville Chamber Music<br />

Montreal Chamber Music<br />

Mahler's 100th:<br />

MTT's Nos. 2, 6, 9<br />

Crakow Phil Festival<br />

Over 500 Reviews

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 1<br />

Contents<br />

Sullivan & Dalton Carnegie’s “Spring for Music” Festival 4<br />

Seven Orchestras, Adventurous Programs<br />

Gil French Cracow’s Mahler Festival 7<br />

Discoveries Abound<br />

Jason Victor Serinus MTT and the San Francisco Symphony 10<br />

Mahler Recapped<br />

Brodie, Serinus & Ginell San Francisco Opera’s Ring Cycle 12<br />

Three Views<br />

Brodie & Kandell Ascension’s New Pascal Quoirin Organ 16<br />

French and Baroque Traditions on Display<br />

Perry Tannenbaum Spoleto USA 19<br />

Renewed Venues, Renewed Spirit<br />

John Ehrlich Boston Early Music Festival 22<br />

Dart and Deller Would Be Proud<br />

Richard S Ginell Mighty Los Angeles Master Chorale 24<br />

Triumphing in Brahms to Ellington<br />

Herman Trotter Buffalo Philharmonic 26<br />

Tyberg Symphony, Hagen Concerto<br />

Melinda Bargreen Schwarz’s 26 Year Seattle Legacy 28<br />

Au Revoir But Not Good-Bye<br />

Bill Rankin Edmonton’s Summer Solstice Festival 30<br />

Chamber Music for All Tastes<br />

Gil French Fayetteville Chamber Music Festival 32<br />

The World Comes to Central Texas<br />

Robert Markow Bang! You’ve Won 34<br />

Montreal Music Competition<br />

Robert Markow Osaka's Competitions and Orchestras 35<br />

<strong>American</strong>, Dutch, French, and Russian Winners<br />

Edward Greenfield Glyndebourne’s First Meistersinger 38<br />

Dressing Well (and Warmly) at Garsington<br />

Coming in the Next Issue:<br />

Festivals Galore:<br />

Bavarian State Opera<br />

Bellingham<br />

Here & There 40<br />

Opera & Concerts Everywhere 42<br />

Critical Convictions 50<br />

Meet the Critic: Don O’Connor 53<br />

<strong>Guide</strong> to <strong>Record</strong>s 54<br />

Collections 178<br />

The Newest Music 227<br />

Broadway 234<br />

Archives 235<br />

Videos 243<br />

Books 254<br />

<strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> Publications 256<br />

Cabrillo<br />

Festival of the Sound<br />

Glimmerglass<br />

Music at Menlo<br />

Ohio Light Opera<br />

And Much More...

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 2<br />

www.<strong>American</strong><strong>Record</strong><strong>Guide</strong>.com<br />

e-mail: subs@americanrecordguide.com<br />

Editor: Donald R Vroon<br />

Vol 74, No 5 September/October 2011 Our 76th Year of Publication<br />

Editor, Music in Concert: Gil French<br />

Art Director: Ray Hassard<br />

Design & Layout: Lonnie Kunkel<br />

..Advertising: Elaine Fine (217) 345-4310<br />

Reader Service: (513) 941-1116<br />

CORRESPONDENTS<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong><br />

ATLANTA: James L Paulk<br />

BOSTON: John W Ehrlich<br />

BUFFALO: Herman Trotter<br />

CHICAGO: John Von Rhein<br />

CLEVELAND: Robert Finn<br />

LOS ANGELES: Richard S Ginell<br />

NEW YORK: Susan Brodie, Joseph Dalton,<br />

Leslie Kandell<br />

SAN FRANCISCO: Jason Victor Serinus<br />

SANTA FE: James A Van Sant<br />

SEATTLE: Melinda Bargreen<br />

LONDON: Edward Greenfield, Kate Molleson<br />

CANADA: Bill Rankin<br />

PHOTO CREDITS<br />

Page 4: Photo by © Steve J. Sherman.<br />

Page 8: Photo by J.Wrzesinski<br />

Page 10: Photo by Bill Swerbenski<br />

Page 11: Photo Courtesy of SFO<br />

Page 12: Photo by Cory Weaver<br />

Page 16 & 18: Phot by Tom Ligamari<br />

Page 19 & 21: Photo by William Struhs<br />

Page 22 & 23: Photos by BEMF.org<br />

Page 24: Photo by Steve Cohn<br />

Page 25: Photo by Lee Salem<br />

Page 27: Photo by Mark Dellas<br />

Page 28: Photo by unknown<br />

Page 31: Photo by Twain Newhart<br />

Page 36: Photo courtesy of Attacca<br />

PAST EDITORS<br />

Peter Hugh Reed 1935-57<br />

James Lyons 1957-72<br />

Milton Caine 1976-81<br />

John Cronin 1981-83<br />

Doris Chalfin 1983-85<br />

Grace Wolf 1985-87<br />

RECORD REVIEWERS<br />

Paul L Althouse<br />

Brent Auerbach<br />

John W Barker<br />

Carl Bauman<br />

Alan Becker<br />

William Bender<br />

John Boyer<br />

Charles E Brewer<br />

Brian Buerkle<br />

Ira Byelick<br />

Stephen D Chakwin Jr<br />

Ardella Crawford<br />

Stephen Estep<br />

Donald Feldman<br />

Elaine Fine<br />

Gil French<br />

William J Gatens<br />

Allen Gimbel<br />

Todd Gorman<br />

Philip Greenfield<br />

Steven J Haller<br />

Lawrence Hansen<br />

Patrick Hanudel<br />

James Harrington<br />

Rob Haskins<br />

Roger Hecht<br />

David Jacobsen<br />

Benjamin Katz<br />

Page 40: Photo by Sussie Ahlberg<br />

Page 38: Photo by Alastair Muir<br />

Page 42: Photo by Scot Ferguson<br />

Page 46: Photo by Bonnie Perkinson<br />

Kenneth Keaton<br />

Barry Kilpatrick<br />

Mark Koldys<br />

Lindsay Koob<br />

Kraig Lamper<br />

Mark L Lehman<br />

Vivian A Liff<br />

Peter Loewen<br />

Ralph V Lucano<br />

Joseph Magil<br />

Michael Mark<br />

John P McKelvey<br />

Donald E Metz<br />

Catherine Moore<br />

David W Moore<br />

Robert A Moore<br />

Kurt Moses<br />

Don O’Connor<br />

Charles H Parsons<br />

David Radcliffe<br />

David Schwartz<br />

Jack Sullivan<br />

Richard Traubner<br />

Donald R Vroon

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 3<br />

Music in Concert highlights<br />

September 7-14<br />

Kent Nagano and the Montreal Symphony celebrate<br />

the gala opening of L’Adresse Symphonique,<br />

Montreal’s new symphony hall,<br />

with works by three Quebec composers and<br />

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9. Four nights later<br />

the Borodin Quartet performs Quartets Nos. 15<br />

by Beethoven and Shostakovich. Then Nagano<br />

inaugurates the MSO’s regular season with<br />

Joshua Bell (Glazounov and Tchaikovsky) and<br />

Messiaen’s Turangalila Symphony with pianist<br />

Angela Hewitt.<br />

September 9-10<br />

Joana Carneiro leads the St Paul Chamber<br />

Orchestra in the world premiere of Nico Muhly’s<br />

Luminous Body. Also on the program are<br />

works by Bach, Haydn, and Brahms at the Ordway<br />

Center.<br />

September 10-30<br />

The San Francisco Opera gives the world premiere<br />

of Christopher Theofanidis’s Heart of a<br />

Soldier with Thomas Hampson, William Burden,<br />

and Melody Moore conducted by Patrick<br />

Summers and directed by Francesca Zambello<br />

at War Memorial Opera House.<br />

September 14-15<br />

The Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio perform<br />

yet another world premiere, Stanley Silverman’s<br />

Piano Trio No. 2, on a program with<br />

Mozart’s Trio, K 502, and Beethoven’s Archduke<br />

at New York’s 92nd Street Y (see a review<br />

of their Danielpour premiere in this issue).<br />

September 23-30<br />

David Robertson and the St Louis Symphony<br />

serve up two weekends of world premieres at<br />

Powell Hall: Steven Mackey’s Piano Concerto<br />

with Orli Shaham plus Mahler’s Symphony No.<br />

1; then Edgar Meyer in his Double Bass Concerto<br />

No. 3 on a program with Copland’s Suite<br />

from The City with film, plus Ives and Gershwin.<br />

September 29<br />

Sitarist Ravi Shankar (we can hope) celebrates<br />

his 91st birthday with a long-awaited, twice-<br />

postponed concert at Disney Concert Hall in<br />

Los Angeles.<br />

September 22-October 1<br />

In his first two weeks as the Seattle Symphony’s<br />

new music director, Ludovic Morlot conducts<br />

Zappa’s Dupree’s Paradise, Dutilleux’s<br />

Tree of Dreams with Renaud Capuçon,<br />

Beethoven’s Eroica, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring,<br />

Gershwin’s <strong>American</strong> in Paris, and Varese’s<br />

Ameriques at Benaroya Hall.<br />

October 4-8<br />

The Brooklyn Academy of Music presents Kurt<br />

Weill’s Threepenny Opera with stage direction<br />

and lighting conceived by Robert Wilson. The<br />

Berlin Ensemble accompanies the US premiere<br />

of this production.<br />

October 6-11 and 14-16<br />

Valery Gergiev and the Mariinsky Orchestra<br />

take Tchaikovsky’s six symphonies (two per<br />

night) first to Carnegie Hall and then to the<br />

University of California-Berkeley’s Zellerbach<br />

Hall. They add an extra night in New York with<br />

the winner of the 14th Tchaikovsky Competition<br />

plus works by Stravinsky and<br />

Shostakovich.<br />

October 16<br />

Pianist Louis Lortie celebrates Liszt’s bicentennial<br />

with the complete Years of Pilgrimage at<br />

the Royal Conservatory’s Koerner Hall in<br />

Toronto.<br />

October 22-23<br />

David Alan Miller leads the Albany Symphony<br />

in the world premiere of Kathryn Salfelder’s<br />

Saxophone Concerto with Timothy McAllister,<br />

plus Kernis’s Concerto with Echoes based on<br />

Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 (also on<br />

the program), and Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony<br />

at Troy Savings Bank Music Hall in Troy<br />

and Skidmore College’s Zankel Music Center<br />

in Saratoga Springs.<br />

AMERICAN RECORD GUIDE (ISSN 0003-0716) is published bimonthly for $43.00 a year for individuals ($55.00 for institutions)<br />

by <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> Productions, 4412 Braddock Street, Cincinnati OH 45204. Phone: (513) 941-1116<br />

E-mail: subs@americanrecordguide.com Web: www.americanrecordguide.com Periodical postage paid at Cincinnati, Ohio.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to <strong>American</strong> <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>, 4412 Braddock Street, Cincinnati, OH 45204-1006<br />

Student rates are available on request. Allow eight weeks for shipment of first copy. CANADIAN SUBSCRIPTIONS: add<br />

$12.00 postage; EUROPE: add $22.00 ALL OTHER COUNTRIES: add $27.00. All subscriptions must be paid with US<br />

dollars or credit card. Claims for missing issues should be made within six months of publication. Retail distribution by<br />

Ubiquity. Contents are indexed annually in the Nov/Dec or Jan/Feb issue and in The Music Index, The International Index<br />

to Music, and ProQuest Periodical Abstracts.<br />

Copyright 2011 by <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> Productions. All rights reserved. Printed in the USA.

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 4<br />

Carnegie’s<br />

“Spring for Music” Festival<br />

Seven Orchestras, Adventurous Programs<br />

[The unique purpose and the principles for<br />

selecting orchestras that perform in the<br />

“Spring for Music” Festival, held in May at<br />

Carnegie Hall and now planned through<br />

2013, is explained at: springformusic.com-<br />

/Mission.htm. Jack Sullivan attended six of<br />

this year’s seven concerts; Joseph Dalton<br />

attended the middle one with the Dallas<br />

Symphony. —Editor]<br />

Jack Sullivan<br />

We hear so many grim stories about the<br />

state of symphony orchestras that it is<br />

heartening to report something good<br />

for a change. “Spring for Music” is a new<br />

annual series of adventurous programs performed<br />

by North <strong>American</strong> orchestras chosen<br />

Carlos Kalmar conducts the Oregon Symphony<br />

by competition. The orchestras, both full-sized<br />

and chamber, played at Carnegie Hall, the<br />

gold standard for orchestral sound, over a hectic<br />

but exciting nine-day period in early May.<br />

All seats were $15 to $25, a brave attempt to<br />

lure younger audiences as well as local folk<br />

flown in from each region (1400 from Toledo,<br />

Ohio, alone for the Toledo Symphony).<br />

Instead of the usual overture-concerto-symphony<br />

formula, each program had to have a<br />

distinct architecture or theme, and there was a<br />

generous amount of contemporary music,<br />

much of it commissioned for the festival.<br />

As a revelation of some regional orchestras<br />

and what they are capable of, “Spring for<br />

Music” was a series of wonderful surprises. It’s<br />

one thing to hear local ensembles on obscure<br />

CDs, quite another to experience them at<br />

4 Music in Concert September/October 2011

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 5<br />

Carnegie Hall cheered on by home supporters<br />

as well as curious New Yorkers who are used to<br />

hearing the Vienna Philharmonic and the<br />

Cleveland Orchestra again and again. Most of<br />

these bands never make it to Carnegie at all;<br />

indeed, the Oregon Symphony had never ventured<br />

west of the Mississippi (simply too<br />

expensive, one of the exhausted but happy<br />

players told me after their concert). Every<br />

orchestra I heard was good, and every one had<br />

a dramatically different sound, rebutting the<br />

cliche that all orchestras these days sound the<br />

same.<br />

The Albany Symphony under David Alan<br />

Miller had the juiciest sonority. Their performance<br />

of Copland’s Appalachian Spring in the<br />

rarely heard “complete” version was one of the<br />

most colorful and memorable I’ve heard in a<br />

very long time (two weeks later I could still<br />

hear it floating through my head). This is not<br />

just because the normally excised material<br />

supplied a dark and startling contrast to the<br />

serene folksiness of what we normally hear, as<br />

if Connotations or some other modernist Copland<br />

piece had suddenly invaded his pastoral<br />

style, but because Albany’s luminous strings,<br />

forceful brass, and vivid winds took the work<br />

to a new level of poetry and theatricality.<br />

The Toledo Symphony under Stefan<br />

Sanderling was more delicate and austere, ideally<br />

suited to whisper the mysterious tremolos<br />

in Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 6; though, at<br />

the end, jeering woodwinds and thundering<br />

timpani showed they could make a big noise<br />

when they needed to. Sanderling brought out<br />

the jarring contrasts and discontinuities in this<br />

eccentric symphony with great skill.<br />

On the same program was the rarely programmed<br />

Every Good Boy Deserves Favor, an<br />

absurdist lampooning of Soviet oppression by<br />

Tom Stoppard and André Previn. It went beautifully<br />

with the symphony, especially since<br />

Previn’s music is a Shostakovich pastiche. This<br />

symphonic playlet from the late 1970s is a risk,<br />

requiring six actors and 94 players who only<br />

perform intermittently, since the “orchestra”<br />

exists in the head of a prisoner in a Soviet<br />

mental institution. Stoppard’s brilliantly sardonic<br />

language was a treat (though the acting<br />

was only adequate), as were Previn’s lively riffs<br />

on Shostakovich.<br />

The presence of fans waving colored hankies,<br />

so obviously proud of their hometown<br />

bands, lent a festive, slightly goofy air to even<br />

the most challenging concerts, including the<br />

Oregon Symphony’s somber wartime program.<br />

All the works in the first half were played<br />

without pause: Ives’s Unanswered Question, so<br />

quiet in Carlos Kalmar’s reading it was almost<br />

ineffable, faded into John Adams’s Wound<br />

Dresser, a tender and poignant depiction of<br />

horror (surely Adams’s most eloquent piece),<br />

its Whitman text subtly sung by Sanford Sylvan.<br />

It too ended quietly, but we were suddenly<br />

jolted out of our seats by the violent timpani<br />

and howling low brass of Britten’s Sinfonia da<br />

Requiem. After the break, the orchestra erupted<br />

into a cathartic, go-for-broke performance<br />

of Vaughan Williams’s Symphony No. 4. The<br />

composer insisted it was not really a wartime<br />

testament, but this explosive reading suggested<br />

otherwise. The Toledo Symphony will play<br />

this same program as part of their 2011-12 season.<br />

The new works at the festival, 18 by my<br />

count, were a decidedly mixed bag. The most<br />

glamorous premiere, Carlos Drummond de<br />

Andrade Stories by the jazz crossover celebrity<br />

Maria Schneider (who conducted the concert),<br />

sounded like air-brushed Villa-Lobos. It was<br />

certainly pleasant enough and was performed<br />

with silky authority by Dawn Upshaw and the<br />

St Paul Chamber Orchestra. Upshaw, who<br />

plans to be regular in the “Spring for Music”<br />

series, made a similar impression in Bartok’s<br />

Five Hungarian Folk Songs. Her unrelenting<br />

earnestness, combined with a smooth arrangement<br />

for string orchestra by Richard Tognetti,<br />

drained these songs of Bartokian color and<br />

charm. This program, the only one without a<br />

theme, included an elegant performance of<br />

Stravinsky’s Concerto in D and a vigorous<br />

account of Haydn’s Symphony No. 104.<br />

Melinda Wagner’s Little Moonhead, an<br />

impressionist palette of seductive moods and<br />

colors, was by far the best of the “New Brandenburgs”<br />

presented by the Orpheus Chamber<br />

Orchestra. As demonstrated by her recent<br />

Trombone Concerto for the New York Philharmonic,<br />

Wagner is an eloquent, poetic voice in<br />

contemporary music. Also on the program<br />

were Aaron Jay Kernis’s charming Concerto<br />

with Echoes (inspired by Brandenberg Concerto<br />

No. 6), Peter Maxwell Davies’s dour and<br />

dreary Sea Orpheus, and Christopher Theofandis’s<br />

gushy, minimalist Muse, which got a loud<br />

ovation from an otherwise frosty New York<br />

crowd (such a contrast to the heartland<br />

whoopers). Only Stephen Hartke and Paul<br />

Moravec, in the finales of Brandenburg<br />

Autumn and Brandenburg Gate, supplied the<br />

requisite neo-classical fizz for a Brandenburg<br />

evening. This was a long, difficult program to<br />

bring off, but Orpheus played with their usual<br />

finesse and authority. The Albany Symphony<br />

will pair the Kernis with the Bach No. 6 on an<br />

October concert.<br />

The other series of new pieces was the<br />

Albany Symphony’s “Spirituals Project” (not to<br />

be confused with Art Jones’s educational project<br />

of the same name, which has been promoting<br />

spirituals for a dozen years): nine new<br />

“spirituals” commissioned by David Alan<br />

Miller, one instrumental work by George Tson-<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> Music in Concert 5

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 6<br />

takis for orchestra and solo “fiddler”, and eight<br />

songs by John Harbison, Daniel Bernard<br />

Roumain, Bun-Ching Lam, Tania Leon, Donal<br />

Fox, Kevin Beavers, Richard Adams, and<br />

Stephen Dankner, all sung by the young<br />

African-<strong>American</strong> baritone De’Shon Myers.<br />

The fiddler, David Kitzis, stole the show in his<br />

procession from one end of Carnegie Hall to<br />

another, his violin resonating brilliantly and<br />

vanishing with ghostly shivers in Carnegie’s<br />

remarkable acoustic.<br />

In his announcement of this ambitious<br />

project, Miller complained about the lack of<br />

worthwhile symphonic spirituals besides Dvorak’s;<br />

yet there is a legacy of “sorrow song”<br />

masterpieces by Delius, Tippett, and Zemlinsky,<br />

not to mention chamber works by Korngold<br />

and Coleridge-Taylor. For the most part,<br />

these blandly meandering arrangements did<br />

little to advance the tradition. The best ones<br />

were Harbison’s playful ‘Ain’t Goin’ to Study<br />

War No Mo’, Adams’s soulful ‘Stan’ Still, Jordan’,<br />

and the finale, Dankner’s ‘Wade in de<br />

Water’, which concluded the series with brilliant<br />

wa-wa effects from the Albany brass.<br />

The final concert in this splendid festival<br />

was played by Kent Nagano and the Montreal<br />

Symphony, who appear with some regularity<br />

in Carnegie Hall. One expected them to be terrific,<br />

and they were. Their program, “The Evolution<br />

of the Symphony”, was no such thing<br />

but, rather, a non-chronological juxtaposition<br />

of textures: Gabrieli’s Symphoniae Sacre,<br />

Webern’s Symphony, and Stravinsky’s Symphonies<br />

of Wind Instruments, all interspersed<br />

with sinfonias by Bach lucidly played by<br />

Angela Hewitt, the whole thing culminating in<br />

a fast, gorgeously articulated Symphony No. 5<br />

by Beethoven. It might seem odd to conclude<br />

an adventurous series with this chestnut, but<br />

we should remember that the Fifth was once<br />

regarded as the most adventurous symphony<br />

of all.<br />

Joseph Dalton<br />

The Dallas Symphony’s May 11 concert at<br />

Carnegie Hall was the only one in the<br />

“Spring for Music” Festival that relied on<br />

a single work. August 4, 1964 by composer<br />

Steven Stucky and librettist Gene Scheer was<br />

premiered in Dallas in September 2008. Best<br />

described as an oratorio, it commemorated the<br />

centennial of President Lyndon Johnson by<br />

centering on two pivotal events: the discovery<br />

in the Mississippi River of three murdered civil<br />

rights workers and a spurious “attack” on two<br />

<strong>American</strong> warships in the Gulf of Tonkin—<br />

they both occurred on the same day.<br />

While the sheer scale of the work must<br />

surely be a point of pride for the DSO, the<br />

piece itself seemed a curious choice for a festi-<br />

val that served as a showcase for orchestras.<br />

With the huge all-volunteer Dallas Symphony<br />

Chorus and four vocal soloists, the orchestra,<br />

led by Music Director Jaap Van Zweden, was<br />

hardly prominent.<br />

Over-arching, though, were the themes of<br />

race, war, and corruption that are still a long<br />

way from being resolved in the <strong>American</strong> psyche.<br />

Granted that’s big stuff for an orchestra to<br />

take on; still, I never felt that the 80-minute<br />

piece elevated the discussion.<br />

Scheer’s libretto, drawing extensively on<br />

historical documents, deals with prejudice and<br />

murder in the south and cataclysmic events in<br />

southeast Asia, all amidst the mundaneness of<br />

a busy day in the White House. Almost none of<br />

it called out for music. Stucky’s settings were<br />

either literal and obvious or melodramatic and<br />

overwrought.<br />

For a tribute to LBJ, the creators didn’t give<br />

the guy many points, casting him as someone<br />

at the mercy of events beyond his control and<br />

making decisions based on incomplete and<br />

inaccurate intelligence. A short scene early on<br />

nicely depicted several aspects of Johnson’s<br />

persona, including his confident swagger, distaste<br />

for intellectuals, and slight paranoia.<br />

Baritone Rod Gilfrey used erratic bits of a<br />

Texan accent. Yet, as the piece progressed, the<br />

role seemed to fall uncomfortably into the<br />

upper reaches of his range. This, combined<br />

with a slow cadence to the words, shrank the<br />

president into someone uncomfortable in his<br />

office, if not his own skin.<br />

Contrast this with tenor Vale Rideout as a<br />

shrieking, hysterical Chicken Little of a defense<br />

secretary (Robert McNamara). The other<br />

soloists, soprano Indira Mahajan and mezzo<br />

Kristine Jepson, portrayed the mothers of slain<br />

civil rights activists who mostly grieved and<br />

sobbed. All four principals were attired in dignified<br />

clothes from the early 60s. The text was<br />

projected, line by line, onto the wall above the<br />

stage.<br />

It fell to the chorus and orchestra to briefly<br />

infuse the evening with poetry and eloquence.<br />

Near the opening, the chorus sang portions of<br />

a poem by Stephen Spender, set in a conservative<br />

style reminiscent of Randall Thompson.<br />

They were prepared by Donald Krehbiel, and<br />

they sang with outstanding clarity and<br />

warmth.<br />

Less moving was a lengthy elegy for<br />

orchestra positioned at the dead center of the<br />

work. Though hushed and deftly scored, its<br />

modest melodic contours felt like little more<br />

than a respite amid the hollow frenzy of the<br />

night.<br />

The 2012 “Spring for Music” Festival, May<br />

7-12, will present the Alabama, Edmonton,<br />

Houston, Milwaukee, Nashville, and New Jersey<br />

orchestras.<br />

6 Music in Concert September/October 2011

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 7<br />

Cracow’s Mahler Festival<br />

Discoveries Abound<br />

Gil French<br />

Last spring the Cracow Philharmonic commemorated<br />

the 100th anniversary of<br />

Mahler’s death by having eight Central<br />

European orchestras perform his 10 symphonies.<br />

Consider it a “Spring for Mahler” Festival,<br />

a parallel to Carnegie Hall’s “Spring for<br />

Music” festival (above). For me it was an occasion<br />

for a number of surprising discoveries.<br />

I was last in Poland in 1987 when the arts,<br />

Catholicism, and Solidarity were the only vital<br />

means of protesting Communism’s weakened<br />

but still firm grip on the country. While architectural<br />

restoration was advanced, cities were<br />

rather grey, tourism was strictly state-controlled,<br />

and alcoholism ravished 20-somethings<br />

still without hope of “a future”.<br />

What a change today! First, Poland is<br />

extremely prosperous. The middle class<br />

thrives. Cities are bright and impeccably clean<br />

(the Poles could teach the Chinese a thing or<br />

two about clean toilets!). Local and intercity<br />

public transportation is superb. Lodging is<br />

first-rate, with bounteous Central European<br />

breakfasts. Tourist spots, rich in history, are<br />

counterpointed by superb museums that contrast<br />

the present with the war years. The arts<br />

are thriving. And from Warsaw to Zakopane<br />

the countryside is beautiful.<br />

The second major discovery: don’t believe<br />

the guidebooks about Warsaw (“Warsaw can<br />

be hard work. It may not be the prettiest of<br />

Polish cities”, says Lonely Planet). The restored<br />

Old Town-New Town tourist area speaks for<br />

itself, though prosperity has forced out street<br />

musicians, hawkers’ stalls, and folk art. The<br />

superb tram and bus system gets you everywhere<br />

(a three-day pass costs only $5.80). The<br />

city is orderly and blessedly quiet—no horns,<br />

no loud music. A new interactive Chopin<br />

Museum can finally be visited without<br />

advanced reservations. The profundity of the<br />

Warsaw Uprising Museum can reduce anyone<br />

to tears. The Museum of the History of Polish<br />

Jews will open in 2012 (until 1939 Poland had<br />

the world’s largest Jewish population). The<br />

Polish National Opera is world-class. And<br />

Antoni Wit closed the Warsaw Philharmonic’s<br />

season with Mahler’s Symphony No. 3, a concert<br />

I had to miss because of the festival three<br />

hours south.<br />

The major discovery at the Mahler Festival<br />

was Pawel Przytocki (PAH-voh Psheh + TROTsky<br />

without the R), general and artistic director<br />

Pawl Przytocki<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> Music in Concert 7

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 8<br />

of the Cracow Philharmonic and world-class<br />

Mahler <strong>conductor</strong>. When asked where his idea<br />

for the festival came from, he said, “From<br />

Mahler’s biography”. By selecting orchestras<br />

from Central European cities where Mahler<br />

himself conducted, Przytocki also created a<br />

platform to boost the reputation of his own<br />

orchestra that he has directed since March<br />

2009, taking it thrice to Vienna’s Musikverein<br />

and twice to Paris’s Theatre du Chatelet.<br />

The concluding June 19 concert of Symphony<br />

No. 8 was unquestionably the high<br />

point of the festival that began May 10. With<br />

the audience facing the rear of the cathedrallike<br />

St Catherine’s Church in Cracow’s Kazimierz<br />

(Jewish) quarter, Przytocki had the<br />

magnificent Cracow and Czech Philharmonic<br />

Choirs (165 singers) facing each other in stalls<br />

left and right, with the Cracow Philharmonic<br />

Boys’, Leipzig MDR Children’s, and Puellae<br />

Orantes Girl’s Cathedral Choir (120 total)<br />

across the back facing him from under the<br />

choir loft where the organist and seven brass<br />

players were found. In front of the Cracow<br />

Philharmonic (expanded from 100 to 120) were<br />

the seven soloists, each so tonally rich and<br />

warm, broadly dynamic yet never strained,<br />

free of uncontrolled vibrato, and perfectly<br />

blended that they deserve listing: sopranos<br />

Barbara Kubiak (Polish), Urska Arlic Gololicic<br />

(Slovenian), and Iwona Socha (Polish); altos<br />

Jadwiga Rappé (Polish) and Ewa Marciniec<br />

(Polish); tenor Roman Sadnik (Viennese), baritone<br />

Adam Kruzel (Polish), and bass Peter<br />

Mikulas (Slovak).<br />

Wide-screen monitors hidden behind massive<br />

pillars aided the coordination, but what<br />

clinched it was Przytocki’s total intellectual<br />

grasp of the score’s form, his attention to fine<br />

orchestral details otherwise easily lost in the<br />

resonant acoustics, his Gergiev-like awareness<br />

and eye-contact with each group, and, above<br />

all, his flexible forward thrust and tight rhythmic<br />

pulse. It took only about two minutes for<br />

ensemble to solidify. By the ends of both the<br />

‘Veni, Creator Spiritus’ and Faust sections, the<br />

emotional effect was quite shattering, as I<br />

learned how to breathe again.<br />

I had learned earlier to approach the festival’s<br />

orchestras with trepidation, and this was<br />

my only chance to hear the Cracow Philharmonic.<br />

Not amorphously subsumed beneath<br />

the vocal forces and resonant acoustics, its<br />

intonation, quality of tone, tight ensemble,<br />

and the superb quality of its principal players<br />

justified its Vienna and Paris invitations.<br />

Before I arrived in Cracow, Przytocki led<br />

his orchestra in Symphony No. 6, and Israeli<br />

Lior Shambadal led it in the Resurrection Symphony.<br />

A week before Mahler’s Eighth, Przytocki<br />

substituted for the Wroclaw Philharmonic’s<br />

Music Director Jacek Kaspszyk in Symphony<br />

No. 7. In the first two movements the<br />

orchestra itself seemed weak. Violins were<br />

lean, the seven growly string basses were hardly<br />

audible, trumpets and French horns had frequent<br />

clams, winds were exposed, and ensemble<br />

wasn’t confident.<br />

Suddenly in the third movement, with<br />

Przytocki’s clarity, dynamism, consummate<br />

communications skills, and tight rhythmic<br />

control, this regional orchestra found its legs.<br />

Tight ensemble and accurate playing yielded<br />

delicate transparecy and flexibility that heaved<br />

and sighed—the same in the fourth as Przytocki<br />

shifted styles mid-measure, drawing ecstatic<br />

playing. By the finale the Wroclaw Phil was like<br />

a sports team that has found its groove, could<br />

do no wrong, and was sure of victory.<br />

I didn’t understand the degree of Przytocki’s<br />

accomplishment until a week later when<br />

Kaspszyk appeared with his orchestra for the<br />

Cooke-Matthews version of Symphony No. 10.<br />

It sounded like a different orchestra; in fact, it<br />

was to some extent—certainly different string<br />

players and without No. 7’s superb concertmaster.<br />

From the very opening unison viola<br />

line, I translated “Kaspszyk” as “joke”. Every<br />

note was detached, almost every horn<br />

entrance was a fart, brass was crass, ensemble<br />

was a mess, and fortes screamed, as Kaspszyk<br />

buried his head in the score, gave jerky highlow<br />

gestures, and proved his lack of familiarity<br />

with and feeling for the score’s magnificent<br />

scope and poignant lines. Judging from his<br />

biography and performance, Kaspszky, now<br />

59, reached the down side of the mountain<br />

very early in his career.<br />

In Symphony No. 5, Jiri Belohlavek, who<br />

becomes music director of the Czech Philharmonic<br />

for the second time in 2012, showed<br />

that he has firmly returned that great organ of<br />

an orchestra (in managerial and player turmoil<br />

for over a decade) to Rolls Royce status. Violas,<br />

cellos, and string bass sections each sound<br />

with one sumptuous tone. There must be a<br />

body-language code to belong to this still overwhelmingly<br />

male ensemble, their intense concentration<br />

and passion is so strong! Belohlavek’s<br />

contrasts in the first two movements<br />

were devastating; the third was a bit heavy,<br />

especially with the Mack truck force of the<br />

principal French horn. The slow Adagio was as<br />

transparent and deeply moving as I’ve ever<br />

heard it. Only in the finale did the orchestra<br />

become so taken with its own weighty sound<br />

that it began to overwhelm the bright acoustics<br />

of Szymanowski Hall.<br />

Another discovery was the work Belohlavek<br />

opened with, Sinfonietta, a graduation<br />

piece by 22-year-old Karel Ancerl, probably the<br />

most precocious, mature student work ever<br />

written. With the style, profundity, and counterpoint<br />

of Martinu’s Double Concerto, plus<br />

the CPO’s sonics and commitment, I couldn’t<br />

understand the audience’s barren response.<br />

8 Music in Concert September/October 2011

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 9<br />

The other orchestras at the Festival all<br />

failed to compensate for the hall’s brightness,<br />

illustrating the difference between power<br />

(Czech Phil) and loudness, caused by inferior<br />

instruments forced beyond their capacities by<br />

unsubtle musicians. Judging from his interpretation<br />

of Songs of a Wayfarer and Symphony<br />

No. 4, Aleksander Marcovic, born in Belgrade<br />

in 1972 and chief <strong>conductor</strong> of the Brno Philharmonic,<br />

has reached the down side of the<br />

mountain exceptionally early. Under his<br />

extremely angular conducting style, the<br />

orchestra looked bored, was poorly tuned, and<br />

had flatulent horns, unsubtle winds, weak<br />

ensemble, and a bashing timpanist. Marcovic<br />

attended only to the melody line, ignoring<br />

Mahler’s wonderful counterpoint and inner<br />

details.<br />

In Wayfarer Lithuanian baritone Vytautas<br />

Juozapaitis, with strained top notes and bottom<br />

notes beyond his range, must have<br />

thought he was at the Met, not in a bright 697seat<br />

hall. Only Polish soprano Anna Pehlken,<br />

deliciously floating as she sang about a heavenly<br />

feast, drew quality out of Marcovic in the<br />

symphony’s final movement.<br />

In Symphony No. 1, despite mellow horns,<br />

Budapest’s Hungarian National Philharmonic<br />

had wiry strings, hollow flutes, weak string<br />

basses, and a timpanist who absolutely bashed<br />

his instruments. None were helped by Music<br />

Director Zoltan Kocsis (the pianist), whose<br />

matter-of-factness seemed indifferent as he<br />

rushed through the work—with a six-minute<br />

‘Blumine’ movement to boot—in 55 minutes.<br />

He didn’t have a clue what this emotional<br />

masterpiece is all about.<br />

In Symphony No. 9, despite raw percussion,<br />

harsh cymbals, awful bass drum, somewhat<br />

blatant French horns, and weak string<br />

basses, the Slovak Philharmonic (another<br />

mostly male bastion) had solid strings. What<br />

they really needed was a <strong>conductor</strong> sensitive to<br />

tone color, who could tame them in the hall’s<br />

bright resonance. Instead, Alexander Rhabari,<br />

a short butterball Iranian and the only festival<br />

<strong>conductor</strong> who worked from memory, was all<br />

large, obvious gestures (two fingers means<br />

this, one point down means that, etc.) and<br />

details, details, details without forward<br />

motion. This has to have been the longest<br />

Mahler Ninth: the first movement took 33 minutes,<br />

the second 20. All trees, no forest. His<br />

metronomic pacing fit the third movement<br />

well enough. Only in the finale did he begin to<br />

develop some long arching lines.<br />

Italian <strong>conductor</strong> Daniele Callegari is<br />

worth keeping an eye out for, especially if he<br />

returns to the Met. Aside from Przytocki, he<br />

was the only other festival <strong>conductor</strong> to get an<br />

orchestra to play “beyond itself”. In Symphony<br />

No. 3 the Slovenian Philharmonic’s lower<br />

strings were raw, woodwinds had a number of<br />

glitches, the principal trombone’s tone wasn’t<br />

secure—nor was the trumpet’s. Yet textures<br />

were transparent, and, even with quick tempos,<br />

Callegari’s forward flexible flow was well<br />

aimed and often buoyant. Ensemble was<br />

excellent. And by the end of the first and last<br />

massive movements, Mahler’s emotional<br />

statement was delivered so powerfully that any<br />

glitches didn’t count.<br />

My other discovery was that most <strong>American</strong><br />

regional orchestras (Buffalo, Rochester,<br />

the ones in the Carnegie “Spring for Music”<br />

Festival) far outclass most of the Central European<br />

orchestras I heard both in technical execution<br />

and musicality. Nor did the festival feel<br />

like one: the concerts weren’t social events at<br />

all—people arrived, heard music, and left.<br />

They were also ritualistic: applause, followed<br />

by standing, followed by unison rhythmic<br />

clapping, and five curtain calls, even for Kaspszyk’s<br />

excruciating Symphony No. 10. De<br />

gustibus.<br />

Yet where other than in Poland is an airport<br />

(Warsaw’s) named for a composer<br />

(Chopin)!<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> Music in Concert 9

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 10<br />

MTT and the San Francisco<br />

Symphony<br />

Mahler Recapped Before European Tour<br />

Jason Victor Serinus<br />

During the centenary of Gustav Mahler’s<br />

death, Michael Tilson Thomas and the<br />

San Francisco Symphony have gone to<br />

great lengths to bolster their reputation as a<br />

world-class “Mahler Orchestra”. Following the<br />

recording of all the symphonies and song<br />

cycles in concert, which they released in<br />

hybrid SACD format, they’ve issued complete<br />

box sets on disc and (soon) vinyl. In addition,<br />

they prepared a two-part “Keeping Score” documentary,<br />

broadcast nationally in June on PBS<br />

and then released in DVD and Blu-Ray formats.<br />

They also programmed Mahler for their<br />

May 19-June 6 European tour of Prague, Vienna,<br />

Brussels, Essen, Luxembourg, Paris,<br />

Barcelona, Madrid, and Lisbon.<br />

As a pre-tour “warm-up”, the orchestra<br />

performed three of Mahler’s symphonies in<br />

early May at their home base, Davies Symphony<br />

Hall. Starting with Symphony No. 9, SFS<br />

launched an ambitious nine-day mini-cycle<br />

that also included the glorious No. 2 and tragic<br />

No. 6.<br />

The orchestra was in top form. My companion<br />

for No. 9, Raymond Bisha, Naxos’s<br />

director of media relations for North America,<br />

has heard many an orchestra in his years as a<br />

classical musician and media professional. Yet<br />

he was struck by the uniform strength of the<br />

ensemble and the fact that he could hear no<br />

weak links. The playing was all of a piece.<br />

It was also, in typical MTT fashion, bright,<br />

bold, filled with color, and impeccably controlled.<br />

The sound may not have that burnished<br />

aged-in-wood patina of some European<br />

orchestras, but neither is it “theatrical”,<br />

as Gramophone suggested when it rated SFO<br />

as No. 13 in its survey of great orchestras<br />

(December 2008). Perhaps they consider “theatrical”<br />

anyone who follows in the footsteps of<br />

Leonard Bernstein, loves Stravinsky and Copland,<br />

and has championed the music of Gershwin<br />

and Jewish theatre.<br />

If there is any truth in the assertion, it may<br />

refer to the fact that MTT, in his concern for<br />

structural coherence, does not always probe<br />

the emotional depths. That was certainly not<br />

the case with his emotionally riveting performance<br />

of No. 9. In no short order, a sense of<br />

tragedy overcame the Andante’s lyrical opening.<br />

After an especially strong statement from<br />

offstage horns, startling drums and cymbals<br />

revealed Mahler at his most emotionally con-<br />

Michael Tilson Thomas<br />

flicted. The up-and-down topsy-turvy nature<br />

of his writing, cogently conveyed, so seized the<br />

audience that you could feel the relief as people<br />

caught their breath and adjusted themselves<br />

at the movement’s conclusion.<br />

In the second movement MTT skillfully<br />

conveyed the manic aspects of what Mahler<br />

termed the “comfortable l„ndler”; despite the<br />

beauty of more pastoral passages, it was<br />

impossible to escape the impression that happiness<br />

was fleeting. The biting horn opening of<br />

the Rondo-Burleske third movement paved<br />

the way for increasingly disturbing music.<br />

Even its most lyrical passages—the magical<br />

harp glissandos, for example—were soon overwhelmed<br />

by angst.<br />

10 Music in Concert September/October 2011

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 11<br />

The beautiful, expansive opening of the<br />

final Adagio brought welcome but transitory<br />

relief. When Thomas (in a gesture I’ve rarely<br />

seen him use) opened his arms wide, the<br />

orchestra responded in kind, sounding as if<br />

they had fully opened their hearts to Mahler’s<br />

plight. The emotion on the faces of many players<br />

further reflected their complete identification<br />

with the composer’s struggle. Rather than<br />

the “grief gives way to peace, music and<br />

silence become one” ending that Michael<br />

Steinberg described in the program notes, the<br />

orchestra seemed to fade into nothingness. It<br />

was as though Mahler had totally surrendered<br />

to inevitable tragedy.<br />

Although the beginning of the Resurrection<br />

Symphony sounded less self-consciously contrived<br />

than on SFSO’s recording of it, the marcato<br />

cello attacks as the music got underway<br />

were precise to a fault. By contrast, the Andante<br />

Moderato (II) was so slow that it lacked<br />

lift. Music that wanted for a smile remained<br />

straight-faced. The third movement, which<br />

Mahler designated “in quietly flowing<br />

motion”, built rapidly to a noisy conflagration.<br />

In the Urlicht, mezzo-soprano Jill Grove,<br />

replacing Sasha Cook, sang beautifully until<br />

the very end, which she cut a mite short.<br />

The final choral movement was another<br />

mixed bag. Although the orchestra played as<br />

beautifully as ever, and the chorus sounded<br />

glorious, the passages denoting the coming of<br />

the light (the “resurrection”) fell short of the<br />

The San Francisco Orchestra<br />

mark. Soprano Karina Gauvin, who seemed ill<br />

at ease in the extremely long wait for her<br />

entrance, began exquisitely, then momentarily<br />

veered far off pitch. She recovered nicely, sang<br />

the repeat perfectly, and proceeded to open<br />

her voice in her duet with Grove to deliver<br />

some of the most beautifully impassioned,<br />

vibrant singing I’ve heard in a long time.<br />

In the tremendous conclusion, the gates of<br />

heaven opened wide and blazing light poured<br />

forth. When I last heard Thomas perform this<br />

symphony at one of the recording sessions, the<br />

climax was a major disappointment. It felt as<br />

though, even with a huge chorus propelling<br />

him forward, he paused at the gates, averted<br />

his eyes, and declared, “I’m not yet ready.”<br />

This time he moved forward, but without the<br />

orgasmic tension and release that make the<br />

Bernstein and Rattle recordings so thrilling.<br />

Everyone onstage seemed to give their all, but<br />

the effect was more visceral than uplifting.<br />

The letdown continued at the performance<br />

of Symphony No. 6. When MTT conducted<br />

and recorded the symphony in September<br />

2001, immediately after 9-11, we could feel the<br />

emotional involvement from first note to last.<br />

This time, the symphony’s happier passages<br />

were more convincing than the tragic ones.<br />

Was he simply unwilling to revisit that week of<br />

intense shock and pain? For whatever reasons,<br />

the Sixth of 5-12 felt more beautifully played<br />

than deeply felt.<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> Music in Concert 11

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 12<br />

San Francisco Opera’s<br />

Ring Cycle<br />

Three Views<br />

[With the Music Critics Association holding<br />

its annual meeting last June during the first<br />

of San Francisco Opera’s three Ring cycles,<br />

I asked three of ARG’s writers to share their<br />

impressions. Susan Brodie covers opera<br />

often for ARG in her trips to Europe. Jason<br />

Victor Serinus, who lives in the Bay Area,<br />

knows the SF Opera well, including the single<br />

productions leading up to the complete<br />

cycle. And Richard S Ginell gave<br />

complete ARG coverage to Wagner’s four<br />

operas in Los Angeles Opera’s 2010-11 season.<br />

—Editor]<br />

Susan Brodie<br />

Andrea Silvestrelli (Hagen) with members of the San Francisco Opera chorus<br />

Francesca Zambello’s Ring Cycle was originally<br />

a Washington National Opera production<br />

billed as a “Ring for America”,<br />

but the company had to abandon the project<br />

for financial reasons before the final installment.<br />

San Francisco Opera seized the opportunity<br />

to complete the cycle for its first new<br />

production since 1999. It was a very good one,<br />

especially for <strong>American</strong> audiences, with just<br />

enough updating and topical relevance to<br />

tickle the intellect without thrusting the viewer<br />

into confusion or outrage.<br />

Zambello has chosen <strong>American</strong> times and<br />

places for the settings and situations of the<br />

Nibelung myth. The Rhinemaidens were Gay<br />

90s wenches and Alberich a gold prospector<br />

(Nibelheim is a gold mine). The gods, gathered<br />

in front of a construction site, were<br />

dressed like characters from The Great Gatsby<br />

(with hard hats), and their rainbow bridge to<br />

Valhalla is the gangplank to the Titanic. Hunding<br />

dwelled in a wood-frame hunting cabin<br />

straight out of Deliverance. Wotan was outargued<br />

by Fricka in a corporate boardroom.<br />

Brunnhilde’s rock was modeled after fortifications<br />

at San Francisco’s Presidio. Mime raised<br />

Siegfried in a camping trailer amply stocked<br />

with Coca-Cola and Rheingold beer. Fafner’s<br />

lair was a chop shop, where Alberich, now a<br />

homeless off-the-grid terrorist living out of a<br />

shopping cart, kept watch while assembling<br />

Molotov cocktails. Gibichung Hall was a glasswalled<br />

Trump-worthy penthouse overlooking<br />

a polluted industrial skyline.<br />

These settings served as cultural references<br />

to heighten an <strong>American</strong> viewer’s connection<br />

with the themes of the work. There<br />

12 Music in Concert September/October 2011

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 13<br />

was almost nothing in Zambello’s staging that<br />

could be considered directorial excess. Beyond<br />

the redwood forests and parachuting WW I<br />

valkyries, this was a very traditional Ring.<br />

Zambello’s only major changes from the<br />

aborted Washington production involved a<br />

reworking of the projections, which for me<br />

proved to be the strongest cohesive element of<br />

the staging and probably the most <strong>American</strong><br />

element, designed for a public accustomed to<br />

watching a screen. Most of the film imagery<br />

came from nature—clouds, rippling waves on<br />

the water’s surface, rocks, forest—or from<br />

man-made urban or industrial scenes. Video<br />

was projected onto two full-stage-wide<br />

screens, one a scrim at the front of the proscenium<br />

that was raised during each scene to<br />

draw the audience closer to the action.<br />

The dual-screen projections created depth<br />

and texture. Variations in the speed of movement<br />

increased Zambello’s control of the<br />

viewer’s experience. Projections were sometimes<br />

static, sometimes subtly moving, like a<br />

movie camera’s slow close-up to suggest emotion.<br />

Orchestral intervals become background<br />

music for panoramic fly-over shots of movement<br />

through space or change of scenery, like<br />

the descent from the gods’ domain to Nibelheim.<br />

As the story progressed, the projections<br />

underlined the environmental subtext with<br />

concrete imagery: the spilling of oil, the progressive<br />

despoiling of river or forest, the death<br />

of nature.<br />

The film also leapt off the screen onto the<br />

stage in the form of special effects: a dazzling<br />

arc of sparks when Donner summoned thunder<br />

and lightning in Rheingold, a lightning<br />

strike as Siegmund pulled the sword from the<br />

tree in Walkure, an explosion when Siegfried<br />

broke the Wanderer’s spear. The Magic Fire at<br />

the end of Walkure was the most stunning I’ve<br />

ever scene: real fire (requiring flame-retardant<br />

costumes and the presence of a fire marshal)<br />

surrounded Brunnhilde’s rock, and projections<br />

of fire on both screens gave depth to the<br />

illusion. Dramatic shifts of stage lighting further<br />

clarifed Zambello’s reading of the text<br />

with great specificity.<br />

Even though this Ring was often staged in<br />

semi-abstract ways, Zambello dug to the emotional<br />

heart of every encounter, establishing<br />

intimacy and teasing out fresh feeling from<br />

small moments via carefully gauged small gestures<br />

and reactions. Each character interacted<br />

physically with the others, from a simple touch<br />

on the arm or clasping of hands to full<br />

embrace. This is by far the most touchy-feely<br />

Ring I’ve ever seen.<br />

Wotan and Fricka were physically affectionate<br />

from their first appearance in Rheingold<br />

until the thwarted, angry Wotan flinched<br />

at his wife’s touch in Walkure. Freia at first suffered<br />

the caresses of the smitten Fasolt with<br />

great unease but returned from captivity blissfully<br />

embracing him, clearly unhappy to return<br />

to the gods. Hunding and Sieglinde groped<br />

one another like teenagers. Brunnhilde<br />

breached the barrier between gods and men to<br />

embrace Siegmund at the moment she understood<br />

his love for Sieglinde. Fafner, once<br />

stabbed, descended from his trash compacter<br />

to express his (ultimate) pity and compassion<br />

for the fate of the uncomprehending Siegfried<br />

with a touch. Even Alberich and Wotan tussled<br />

mano a mano when they met in Siegfried. The<br />

constant physical engagement along with<br />

other aspects of Zambello’s detailed direction<br />

infused humanity into these sometimes<br />

abstract mythological characters.<br />

The theatrical and cinematic details were<br />

fascinating, but the success of a Ring cycle<br />

depends on the musical values. San Francisco’s<br />

forces were solid but rarely rose to a<br />

thrilling level. Rheingold started with a lurch,<br />

as though someone had clumsily dropped the<br />

needle onto a vinyl record, and the pacing and<br />

dynamics showed limited nuance. The brass<br />

had difficulties in all four operas, and at least<br />

from my seat in the rightmost orchestra section<br />

there were strange balance problems.<br />

Things did improve, however, over the<br />

course of the cycle. By the middle of Walkure’s<br />

Act I the pacing became more expressive, with<br />

an urgency to the Siegmund-Sieglinde dialog<br />

that suggested lovemaking. By Siegfried the<br />

orchestra participated dramatically to a much<br />

greater degree. But the brass often weren’t up<br />

to the task, and I heard a surprising number of<br />

intonation problems, not to mention a lack of<br />

coordination between stage and pit. The Gotterdammerung<br />

I heard in Paris three days later<br />

showed much greater precision and clarity of<br />

sound from the orchestra.<br />

Casting was strong, given the voices available<br />

today. Nina Stemme was a fine and feisty<br />

Brunnhilde, though some signs of strain gave<br />

the impression of a singer not at her best. Mark<br />

Delavan’s impetuous and detailed Wotan<br />

couldn’t be bettered dramatically (most chilling<br />

moment: when he embraced the victorious<br />

Hunding and then nonchalantly broke his<br />

neck), but too often he was inaudible. Gordon<br />

Hawkins as Alberich was stronger both vocally<br />

and dramatically in Siegfried than Walkure.<br />

Both Siegfrieds—Jay Hunter Morris in Siegfried<br />

and Ian Storey in Gotterdammerung—looked<br />

and acted the part but had vocal problems.<br />

Brandon Jovanovich contributed youthful<br />

good looks and a strong tenor sound as Froh;<br />

in his role debut as Siegmund, he showed<br />

potential to become a Siegmund for our time.<br />

Andrea Silvestrelli was perhaps the most<br />

impressive voice in the production, a booming<br />

Fasolt (why not Fafner?) and a menacing<br />

Hagen. Melissa Citro played a knockout<br />

blonde-bimbo Gutrune (also Freia), though<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> Music in Concert 13

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 14<br />

vocal glamor was lacking. The Rhinemaidens—Stacey<br />

Tappan, Lauren McNeese, and<br />

Renee Tatum—sounded absolutely glorious.<br />

Jason Victor Serinus<br />

From June 14 to 19 San Francisco Opera<br />

presented the first of its three complete<br />

cycles of Wagner’s Ring. Despite a lessthan-perfect<br />

cast, the power of stage director<br />

Francesca Zambello’s production, Michael<br />

Yeargan’s sets, Jan Hartley and Katy Tucker’s<br />

all-important projections, and the enveloping<br />

waves of Donald Runnicles’s occasionally<br />

overpowering orchestral eloquence made for a<br />

haunting experience.<br />

Much of the effectiveness of Zambello’s<br />

production came from the sets and projections.<br />

All images were drawn from America’s<br />

past and present. The production’s unified<br />

vision owed much to its ever-engrossing projections,<br />

which contrasted the beauty of<br />

forests, canyons, water, and clouds with the<br />

ugliness of railroad tracks and soot-spewing<br />

smokestacks. What some conservative critics<br />

decried as a heavy-handed attempt to saddle<br />

Wagner’s Ring with contemporary relevance<br />

instead brilliantly tapped into the audience’s<br />

collective unconscious, bringing Wagner’s<br />

messages of unbridled greed and abuse of the<br />

natural order to the fore.<br />

Zambello’s Ring remains, by her own<br />

admission, a work-in-process. The cycle’s first<br />

three operas had their production premieres<br />

in Washington DC. Since then, she has<br />

changed emphasis. While the DC productions,<br />

taking their cue from the role the city plays in<br />

world affairs, centered on the misuse of political<br />

power, San Francisco’s remounting drew<br />

on California’s consciousness of nature and<br />

the environment to place more emphasis on<br />

despoliation.<br />

In addition to reconceiving video and<br />

choreography for Act III of Walkure, Zambello<br />

also beefed up the conclusion of Gotterdammerung,<br />

which was first given in a standalone<br />

performance on June 5. That performance’s<br />

very short-lived fizzle of a fire, which<br />

left cast members gazing off into the darkness<br />

of a bare, black stage, was given a much-needed<br />

boost of metaphorical lighter fluid by the<br />

time the opera reappeared in the complete<br />

cycle.<br />

Zambello’s meticulousness let no one get<br />

by with “stand and sing”. Besides such wonders<br />

as the three perfect cartwheels and hilarious<br />

dance of Mime (the sensational David<br />

Cangelosi), Zambello’s constant attention to<br />

the interplay of men and women added extra<br />

dimensions of meaning. Especially delicious<br />

were the ever-changing, often-hilarious facial<br />

expressions of Gutrune (Melissa Citro), whose<br />

droll Anna Nicole Smith-like posing compensated<br />

for wild upper notes. Just as notable<br />

were Sieglinde’s (Anja Kampe) fluctuation<br />

between revulsion for Hunding (Daniel Sumegi)<br />

and futile attempts to turn him around<br />

through loving embrace, Gutrune’s surprising<br />

interplay with Hagen in their brief TV-watching<br />

bed scene, and Wotan’s brutality with Erda<br />

(Ronnita Miller) in their final interaction.<br />

At the conclusion of the Immolation Scene,<br />

women briefly held the stage. After the Rhinemaidens<br />

and a very sympathetic Gutrune<br />

brought Siegfried’s body to the unseen funeral<br />

pyre, the Rhinemaidens suffocated Hagen as a<br />

chorus of women watched Brunnhilde (Nina<br />

Stemme) descend to her death. Zambello’s<br />

heart-touching testament to the transcendent<br />

power of sisterhood and later surprising affirmation<br />

of future resurrection linger in the<br />

memory as much as Stemme’s astounding<br />

artistry.<br />

A major vocal rebalancing act occurred<br />

between SFO’s stand-alone premieres of<br />

Siegfried (May 29) and Gotterdammerung<br />

(June 5) and their complete cycle productions.<br />

Jay Hunter Morris, whose hardly-the-hero<br />

Siegfried had difficulty projecting over the<br />

orchestra on May 29, noticeably beefed up his<br />

sound for the cycle without running out of<br />

steam. Concurrently, the magnificent Stemme,<br />

who sang him into the ground on May 29, held<br />

her voice back until Gotterdammerung’s climactic<br />

Immolation Scene. Only then did she<br />

sing with the breathtaking power and generosity<br />

of glorious tone of the individual premieres<br />

a few weeks before. Stemme’s modulation was<br />

especially important on June 19 in Gotterdammerung,<br />

where Ian Storey as Siegfried<br />

progressively lost power owing to illnessinduced<br />

dehydration. Only after treatment by<br />

a physician was he able to return to something<br />

resembling the heroic form he displayed on<br />

June 5.<br />

Volumes could be written about Stemme’s<br />

achievement. Despite short-shifting a few top<br />

notes and fudging her trills, her string of high<br />

Cs in her ‘Hijatoho’ entrance were dispatched<br />

with the carefree impetuosity of youth. The<br />

contrast with Delavan’s performance—wellnuanced,<br />

but lacking in volume and physically<br />

congested—was unfortunate.<br />

Just as disappointing was Brandon<br />

Jovanovich’s deliciously hunky, initially<br />

promising Siegmund, which failed to build<br />

tension; his crucial interplay with Kampe had<br />

all the intimacy of lovemaking by cell phone.<br />

Indeed, besides Stemme, it was Stefan Margita’s<br />

ever-insinuating Loge, Cangelosi’s<br />

superbly sung and acted Mime, Silvestrelli’s<br />

towering dark-voiced Hagen, Stacey Tappan’s<br />

endearing Forest Bird, and the superbly bal-<br />

14 Music in Concert September/October 2011

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 15<br />

anced Rhinemaidens trio (including Tappan)<br />

that deserve the most accolades.<br />

Richard S Ginell<br />

Last year, Los Angeles made its first homegrown<br />

attempt at staging a complete<br />

Wagner Ring cycle, beating upstate rival<br />

San Francisco to the punch, even though the<br />

SF Ring was launched a year before LA’s. But<br />

in the end, San Francisco Opera, whose Ring<br />

performance tradition dates back to 1935, had<br />

the last word in almost every way. Here was a<br />

screwball concept with a huge emotional payoff<br />

because stage director Francesca Zambello<br />

took the trouble to develop her ideas along the<br />

lines of what Wagner wrote (what a novel<br />

notion!).<br />

Whereas the LA stage director Achim Freyer<br />

didn’t particularly care about Wagner’s<br />

characters—or whether you cared about them,<br />

Zambello had her cast probe deeply into their<br />

personalities, virtues, faults, passions, and<br />

capacities for growth. Whereas Freyer set his<br />

Ring on some kind of cold, alien planet populated<br />

by hideous caricatures, Zambello’s<br />

Ring—with its <strong>American</strong> settings from the 19th<br />

Century to the present and near future—connected<br />

with its intended audience on a familiar<br />

human level. Whereas Freyer’s cast was<br />

hamstrung and straitjacketed by his rigid staging—sometimes<br />

no better than a concert performance<br />

with pictures, Zambello’s singing<br />

actors were encouraged to develop all kinds of<br />

physical actions and nuances, large and small,<br />

that illuminated the storyline and libretto.<br />

Zambello has said that her Ring conception<br />

evolved over time into a fable about the<br />

destruction of the environment. Indeed,<br />

Rheingold looked different from and felt more<br />

unified than the stand-alone performance in<br />

2008. I sensed less emphasis on the California<br />

Gold Rush origins of the tale and more on the<br />

pristine natural world that is gradually darkened<br />

by civilization’s pollution and waste as<br />

the cycle proceeded. There were cinematic references<br />

(the West Side Story Siegmund-Hunding<br />

street fight under a crumbling freeway<br />

overpass stands out), lots of weird humor<br />

(Siegfried slaying the 2-1/2-ton scrap-metalcompactor<br />

“dragon” by short-circuiting it with<br />

his sword; Gutrune and Alberich playing with a<br />

TV remote control in a modern, super-sleek<br />

Marriott-like hotel; the parachuting Valkyries),<br />

and recurring social themes (people who lost<br />

control of the ring often ended up homeless,<br />

when not dead).<br />

Granted, Zambello indulged in a speculative<br />

agenda of having no less than three female<br />

characters (Freia, Sieglinde, and Gutrune) feeling<br />

attracted to dangerous men (Fasolt, Hunding,<br />

and Hagen). Yet, in Gutrune’s case, I<br />

found that it contributed to the power of the<br />

production, as it set the stage for Gutrune’s<br />

unusual development from a bored wanton<br />

vamp into a high-minded handmaiden to<br />

Brunnhilde’s and the Rhinemaidens’ redemption<br />

of the world. Indeed Zambello’s conclusion<br />

to Gotterdammerung was quite touching—a<br />

small child planting a single sapling<br />

after the end of the gods, which, unlike Freyer’s<br />

sickening dismantling of his set, meshed<br />

with what Wagner’s music says. Zambello<br />

made us feel good walking out of the opera<br />

house, whereas with Freyer one regretted not<br />

packing those stale tomatoes one was saving<br />

for just the proper occasion.<br />

Beyond the staging, there were two triumphant<br />

performances in this Ring that will<br />

be remembered for a long time. One came<br />

from the pit. While Rheingold was considerably<br />

better-paced and more emphatic in<br />

rhythm than the 2008 performance, Donald<br />

Runnicles kicked things into an even higher<br />

gear in the closing minutes of Act II of<br />

Walkure, and he rode that wave through the<br />

rest of the cycle. Probably his greatest moment<br />

occurred at the closing heights of the<br />

Brunnhilde-Siegfried love duet in Gotterdammerung;<br />

he took off in recklessly thrilling<br />

overdrive, nearly losing control, but his excellent<br />

orchestra saw it through. He was more of a<br />

racehorse than a brooding philosopher in this<br />

Ring, but there are few that are as good at it as<br />

he is these days.<br />

The other big triumph was Nina Stemme<br />

as Brunnhilde, where the promise she showed<br />

in 2010s SFO Walkure blossomed in her first<br />

complete cycle. Here was a strong, amplevoiced,<br />

steady heldensoprano in a compact<br />

body, a playful tomboy Brunnhilde who never<br />

entirely lost that aspect even as she acquired<br />

wisdom and maturity.<br />

Mark Delavan’s now-and-then powerful<br />

Wotan did not eclipse memories of James<br />

Morris and Thomas Stewart from the 1985 SFO<br />

Ring; nor could either of the Siegfrieds (Jay<br />

Hunter Morris in Siegfried and the -indisposed<br />

Ian Storey in Gotterdammerung) keep pace<br />

with Stemme’s Brunnhilde. But there were<br />

ample compensations elsewhere: Andrea Silvestrelli’s<br />

genuine bass Hagen, Gordon<br />

Hawkins’s burly bullying Alberich, David Cangelosi’s<br />

almost lyrical Mime, and Anja Kampe’s<br />

pointed, lustrous Sieglinde.<br />

One could also single out Brandon<br />

Jovanovich’s youthful Siegmund for cheers;<br />

but Los Angeles easily trumped San Francisco<br />

with its incomparable Placido Domingo as<br />

Siegfried. It was one of only a few instances<br />

where the LARing wasn’t outpointed by the<br />

gripping competition from the Bay Area.<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Record</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> Music in Concert 15

Sig01arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:46 PM Page 16<br />

Ascension’s New Pascal<br />

Quoirin Organ<br />

French and Baroque Traditions on Display<br />

Susan Brodie<br />

Manton Memorial Organ, 3-Manual Mechanical Action Core Console<br />

With the installation of the Manton<br />

Memorial Organ, the Church of the<br />

Ascension in Manhattan’s Greenwich<br />

Village has enhanced its long tradition of<br />

musical and artistic excellence. On May 5<br />

<strong>American</strong> Jon Gillick, a Messiaen specialist<br />

long associated with this church, inaugurated<br />

the new instrument with a concert of 19th and<br />

20th Century French music on the larger of its<br />

two component organs.<br />

16 Music in Concert September/October 2011

Sig02arg.qxd 7/22/2011 4:48 PM Page 17<br />

The design was developed by the firm of<br />

Pascal Quoirin of St-Didier, France, in conjunction<br />

with Gillock and Ascension Music<br />

Director Dennis Keene, who sought an instrument<br />

suitable for the widest possible repertoire.<br />

It is a novel two-in-one: a large electricaction<br />

four-manual French 19th-Century one<br />

and a smaller tracker-action three-manual<br />

baroque style organ. They share pipes. (A<br />

technical description with registration details<br />

and photographs are available on the<br />

builder’s website: www.atelier-quoirin.com.)<br />

The handsome consoles and pipes, at the<br />

front of the church, are decorated with stylized<br />

art nouveau trim that harmonizes with<br />

the sober yet rich Gothic revival interior of the<br />

church (a national historic landmark), remodeled<br />

in the 1880s by McKim, Meade, and<br />

White. Hand-carved birds decorating the pipe<br />

cases honor Olivier Messiaen, who drew inspiration<br />

from birdsong.<br />

This concert was a good survey of music<br />

conceived for the classic French organ as<br />

developed by 19th-Century maker Aristide<br />

Cavaille-Coll, with its greatly expanded sound<br />

palette. The tradition is rigorous in the musical<br />

and instrumental skills demanded, dynastic in<br />

the succession of the most important organist<br />

jobs (giving access to the best instruments),<br />

and, with much of the music written for the<br />

Catholic church, rooted in faith. Composers<br />

represented on the program formed a roll call<br />

of the most important practitioners of this art.<br />

For the concert the large, curved fourmanual<br />

console was moved from its normal<br />

position at the front of the left aisle to sit in<br />

front of the altar with the keyboard facing the<br />

pews at a slight angle. Most organ recitalists<br />

play seated in an organ loft, almost invisible,<br />

so it was an unusual view. Gillock walked out,<br />

bowed modestly, turned his back, removed<br />

his jacket (revealing a spiffy brocade waistcoat),<br />

and slipped onto the bench to play.<br />

Marcel Dupré’s Cortege and Litany started<br />

softly, sounding like a processional heard<br />

through the doors of a country church. An<br />

opening four-note bell-like motif expanded to a<br />

folk-like theme that lent itself to shifting meters<br />

and an array of tone colors showing off the registrations,<br />

as the sound swelled to a powerful<br />

finish. It was followed by the more formally<br />

structured Prelude, Fugue, and Variation by<br />

Cesar Franck, which gave a fuller sense of the<br />

symphonic capabilities of the instrument as<br />

well as Gillock’s nimble control of the pedals.<br />

A trademark of the French organ school is<br />

improvisation; Conservatoire students still get<br />

a thorough grounding in keyboard harmony<br />

and counterpoint that enables them to improvise<br />

for unpredictable amounts of time during<br />

church services. Past masters of this art drew<br />

large audiences eager to hear their extended<br />

improvisations on a theme supplied to the<br />

soloist at the last minute. Transcriptions of<br />

two such improvisations, notated from<br />

recordings, gave the nod to Notre Dame<br />

organist Pierre Cochereau (1924-84), who<br />

crafted boldly dissonant variations on a lullaby<br />

by the organist Louis Vierne, and to Charles<br />

Tournemire (1870-1939), titulaire at St-<br />