JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC EXPLORATION - Society for Scientific ...

JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC EXPLORATION - Society for Scientific ...

JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC EXPLORATION - Society for Scientific ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

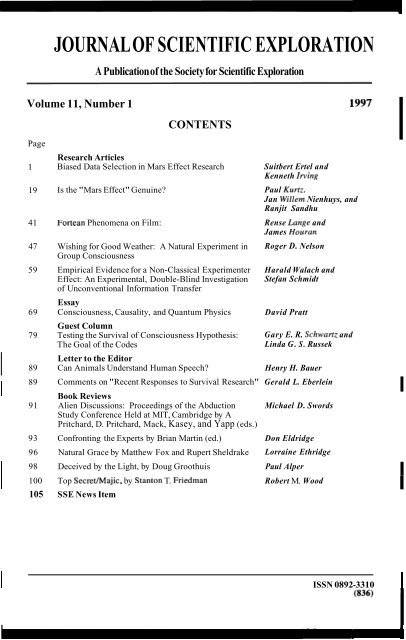

<strong>JOURNAL</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>SCIENTIFIC</strong> <strong>EXPLORATION</strong><br />

A Publication of the <strong>Society</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration<br />

Volume 11, Number 1 I<br />

CONTENTS I<br />

Page<br />

Research Articles<br />

1 Biased Data Selection in Mars Effect Research Suitbert Ertel and<br />

Kenneth Irving<br />

19 Is the "Mars Effect" Genuine?<br />

41 Fortean Phenomena on Film:<br />

Paul Kurtz,<br />

Jan Willem Nienhuys, and<br />

Ranjit Sandhu<br />

Rense Lunge and<br />

James Houran<br />

47 Wishing <strong>for</strong> Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Roger D. Nelson<br />

Group Consciousness<br />

59 Empirical Evidence <strong>for</strong> a Non-Classical Experimenter Harald Walach and<br />

Effect: An Experimental, Double-Blind Investigation Stefan Schmidt<br />

of Unconventional In<strong>for</strong>mation Transfer<br />

Essay<br />

69 Consciousness, Causality, and Quantum Physics David Pratt<br />

Guest Column<br />

79 Testing the Survival of Consciousness Hypothesis: Gary E. R. Schwartz and<br />

The Goal of the Codes Linda G. S. Russek<br />

Letter to the Editor<br />

89 Can Animals Understand Human Speech? Henry H. Bauer<br />

1 89 Comments on "Recent Responses to Survival Research" Gerald L. Eberlein I<br />

Book Reviews<br />

91 Alien Discussions: Proceedings of the Abduction Michael D. Swords<br />

Study Conference Held at MIT, Cambridge by A<br />

Pritchard, D. Pritchard, Mack, Kasey, and Yapp (eds.)<br />

93 Confronting the Experts by Brian Martin (ed.) Don Eldridge<br />

96 Natural Grace by Matthew Fox and Rupert Sheldrake Lorraine Ethridge<br />

1 98 Deceived by the Light, by Doug Groothuis Paul Alper I<br />

1 100 Top SecretIMajic, by Stanton T. Friedman Robert M. Wood I<br />

105 SSE News Item<br />

1 ISSN 0892-3310 1

<strong>JOURNAL</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>SCIENTIFIC</strong> <strong>EXPLORATION</strong><br />

A Publication of the <strong>Society</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration<br />

Volume 11, Number 2 1997<br />

Page<br />

Research Articles<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Apparent Association Between Effect Size in Free<br />

Response Anomalous Cognition Experiments and<br />

Local Sidereal Time<br />

Evidence in Support of the Hypothesis that Certain<br />

Objects on Mars are Artificial in Origin<br />

The Astrology of Time Twins: A Re-Analysis<br />

Commentary on French et al.<br />

Reply to Roberts<br />

Unconscious Perception of Future Emotions:<br />

An Experiment in Presentiment<br />

A Bayesian Maximum-Entropy Approach to<br />

Hypothesis Testing, <strong>for</strong> Application to RNG and<br />

Similar Experiments<br />

Planetary Diameters in the Surya-Siddhanta<br />

Essay<br />

Science of the Subjective<br />

Guest Column<br />

Curious, Creative and Critical Thinking<br />

Letters to the Editor<br />

Comments on "Wishing <strong>for</strong> Good Weather" & Reply<br />

On the Wood Book Review of "Top Secret/Magic9<br />

Comments and Replies<br />

Fortean Phenomena on Film? & Reply<br />

Answer to: "Can Animals Understand Human Speech?'<br />

Book Reviews<br />

Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the<br />

Meanings of Life by Daniel C. Dennett<br />

Review of 3 Books on the "Bell Curve"<br />

Leaps of Faith by Nicholas Humphrey<br />

Leaps of Faith by Nicholas Humphrey<br />

Review of 8 Books on "Prostrate Cancer"<br />

Expedientes Insolitos by Vincente J. Ballester Olmos<br />

S. J. P. Spottiswoode<br />

Mark J. Carlotto<br />

C. C. French, G. Dean<br />

and A. Leadbetter<br />

Peter Roberts<br />

C. C. French, et al.<br />

Dean I. Radin<br />

l? A. Sturrock<br />

Richard Thompson<br />

Robert G. Jahn and<br />

Brenda J. Dunne<br />

P. A. Sturrock<br />

I. Woodhouse/R. Nelson<br />

J. Vallee/R. Wood<br />

K. Randle/S. Friedman<br />

A. Imich/J. Houran&R. Lunge<br />

Remy Chauvin<br />

Carl Hester<br />

Paul Alper<br />

Paul AlpedHenry Bauer<br />

Ian Stevenson<br />

Paul Alper<br />

Richard Haines<br />

ISSN 0892-3310<br />

(836)

<strong>JOURNAL</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>SCIENTIFIC</strong> <strong>EXPLORATION</strong><br />

Volume 11, Number 3<br />

Page<br />

A Publication of the <strong>Society</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration<br />

CONTENTS<br />

Research Articles<br />

263 Accessing Anomalous States of Consciousness with<br />

a Binaural Beat Technology<br />

275 The "Mars Effect" As Seen by the Committee PARA<br />

297 Astrology and Sociability: A Comparative Analysis<br />

of the Results of a Psychological Test<br />

3 17 Report of Referee on Fuzeau-Braesch<br />

320 Reply to McGrew<br />

323 A Psychological Comparison Between Ordinary<br />

Children and Those Who Claim Previous-Life<br />

Memories<br />

337 Did Life Originate in Space? A Discussion of the<br />

Implications of Recent Research<br />

Review Article<br />

345 Correlations of Random Binary Sequences With<br />

Pre-Stated Operator Intention: A Review of a<br />

1 2-Year Program<br />

Essay<br />

369 The Hidden Side of Wolfgang Pauli: An Eminent<br />

Physicist's Extraordinary Encounter With Depth<br />

Psychology<br />

Guest Column<br />

Who Lives'? Who Dies? Helpless Patients and ESP<br />

Letters to the Editor<br />

Comments on Walach & Schmidt<br />

Response to Houtkooper and Vaitl<br />

U.S.-Soviet Disin<strong>for</strong>mation Game<br />

Response to Playfair<br />

Book Reviews<br />

The Biological Universe: The Twentieth-Century<br />

Extraterrestrial Life Debate by Steven Dick<br />

Philosophical Interactions With Parapsychology:<br />

Major Writings of H. H. Price, ed. Frank Dilley<br />

The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal, ed. Gordon Stein<br />

The AIDS Cult: Essays on the Gay Health Crisis by<br />

John Lauritsen & Ian Young<br />

Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and<br />

Creative Lives by Frank Sulloway<br />

F. Holmes Atwater<br />

J. Dommanget<br />

S. Fuzeau-Braesch<br />

John H. McGrew<br />

S. Fuzeau-Braesch<br />

Erlendur Haraldsson<br />

Anthony Mugan<br />

R. G. Jahn, B. J. Dunne,<br />

R. D. Nelson, Y. H. Dobyns<br />

and G. J. Bradish<br />

Harald Atmanspacher and<br />

Huns Primas<br />

Arthur S. Berger<br />

J. Hootkooper & D. Vaitl<br />

H. Waluch & S. Schmidt<br />

Guy Playfair<br />

H. Puthoff<br />

Michael E. Zimmerman<br />

James M. 0. Wheatley<br />

Carlos S. Alvarado<br />

Henry H. Bauer<br />

Henry H. Bauer<br />

- -<br />

ISSN 0892-3310<br />

(836)

"7 1t4 <strong>JOURNAL</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>SCIENTIFIC</strong> <strong>EXPLORATION</strong><br />

A Publication of the <strong>Society</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration<br />

Volume 11, Number 4 1997 I<br />

CONTENTS I<br />

Page<br />

Research Articles<br />

435 Topographic Brain Mapping of UFO Experiencers Norman S. Don and<br />

Gilda Moura<br />

455 Toward a Model Relating Empathy, Charisma, James M. Donovan<br />

and Telepathy<br />

473 The Zero-Point Field and the NASA Challenge to Bernhard Haisch and<br />

Create the Space Drive Alfonso Rueda<br />

487 Motivation and Meaningful Coincidence: A Further T. C. Rowe, J. M. Lemke, E. PI<br />

Examination of Synchronicity Pitsch, and D. B. Henderson<br />

Essays<br />

499 A Critique of Arguments Offered Against<br />

Reincarnation<br />

527 The Archaeology of Consciousness<br />

Guest Column<br />

539 Academic Science and Anomalies<br />

Book Reviews<br />

The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental<br />

Theory by David J. Chalmers<br />

The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental<br />

Theory by David Chalmers<br />

The Oz Files by Bill Chalker<br />

A Skeptics Guide to the New Age by Harry Edwards<br />

Close Encounters? Science and Science Fiction<br />

by R. Lambourne, M. Shallis, and M. Shortland<br />

The Great Dinosaur Extinction Controversy by<br />

Charles Officer and Jake Page<br />

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle<br />

in the Dark by Carl Sagan<br />

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle<br />

in the Dark by Carl Sagan<br />

Additional Comments on Carl Sagan<br />

In the Footsteps of the Russian Snowman<br />

by Dmitri Bayanov<br />

Reincarnation: A Critical Examination by<br />

Paul Edwards<br />

Forming Concepts in Physics by Georg Unger<br />

SSE News Item<br />

Index: Volume 11<br />

Robert Almeder<br />

Paul Devereux<br />

Halton Arp<br />

John Beloff<br />

Robert Almeder<br />

Don Eldridge<br />

Thomas E. Bullard<br />

Henry H. Bauer<br />

John O'M. Bockris<br />

Henry H. Bauer<br />

Ian Stevenson<br />

Edward Winn<br />

James G. Matlock<br />

I<br />

ISSN 0892-3310<br />

(836) I

[s] <strong>JOURNAL</strong> <strong>OF</strong> <strong>SCIENTIFIC</strong> <strong>EXPLORATION</strong><br />

(ISSN 0892-33 10)<br />

A Publication of the <strong>Society</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration<br />

Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Bernhard Haisch<br />

Executive Editor, Marsha Sims<br />

Associate Editor, Dr. Dean Brown and Dr. Mark Rodeghier<br />

Editorial Assistants, Diane Foerder, Yanina Greenstein, Elizabeth Henderson,<br />

Erin Thompson<br />

Editorial Office: Journal of <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration, P.O. Box 5848, Stan<strong>for</strong>d, CA 94309-5848<br />

Telephone: 650-593-858 1, FAX: 650-595-4466<br />

Internet electronic mail - sims@jse.com World Wide Web - http://www.jse.com<br />

Book Review Editor, Dr. Roger Nelson, School of Engineering, Princeton Univ.<br />

Associate Book Review Editors<br />

Prof. Henry Bauer, Dept. of Chemistry, Virginia Polytechnic Inst. & State University<br />

Ms. Dawn Hunt, Health Sciences Center, Univ. of Virginia<br />

Prof. David Jacobs, Dept. of History, Temple University<br />

Dr. Arnold Lettieri, School of Engineering, Princeton University<br />

Mr. P. D. Moncrief, Memphis, TN<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Prof. Remy Chauvin, Sorbonne, France<br />

Prof. Olivier Costa de Beauregard, University of Paris, France<br />

Dr. Steven J. Dick, U. S. Naval Observatory, Washington, DC<br />

Dr. Alan Gauld, Dept. of Psychology, Univ. of Nottingham, UK<br />

Prof. Richard C. Henry, Dept. of Physics & Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University<br />

Prof. Robert Jahn, School of Engineering, Princeton University<br />

Prof. W. H. Jefferys, Dept. of Astronomy, University of Texas<br />

Dr. Wayne B. Jonas, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD<br />

Prof. Kunitomo Sakurai, Institute of Physics, Kanagawa University, Japan<br />

Prof. Ian Stevenson (Chairman), Health Sciences Center, University of Virginia<br />

Prof. Peter Sturrock, Ctr. <strong>for</strong> Space Science & Astrophysics, Stan<strong>for</strong>d University<br />

Prof. Yervant Terzian, Dept. of Astronomy, Cornell University<br />

Prof. N. C. Wickramasinghe, School of Mathematics, Univ. College Cardiff, UK<br />

SUBSCRIPTIONS AND BACK ISSUES: Please use the order <strong>for</strong>ms in the back.<br />

It is a condition of publication that submitted manuscripts have not been published and are not simultaneously submitted<br />

elsewhere. By submitting a manuscript, the authors agree that the copyright <strong>for</strong> their article is transferred to<br />

the publisher if and when the article is accepted. The copyright covers the exclusive rights to reproduce and distribute<br />

the article, including other reproductions and translations. Articles may be photocopied <strong>for</strong> noncommercial research,<br />

teaching or classroom usage. Permission to re~roduce articles in other ~ublications mav be reauested bv<br />

Journal of Scienti$c Exploration (ISSN 0892-3310) is published quarterly in March, June, Septem-<br />

ber and December by the <strong>Society</strong> of <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration, P. 0. Box 5848, Stan<strong>for</strong>d CA 94309-<br />

5848. Private subscription rate: US $50.00 per year (plus $5.00 postage outside USA). Institutional<br />

and Library subscription rate: US $100.00 per year. periodical postage paid at Palo Alto, CA, and ad-<br />

ditional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to:<br />

Journal of ScientiJic Exploration, P. 0. Box 5848, Stan<strong>for</strong>d CA 94309-5848.

Journal of ScientiJic Exploration, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 1-18, 1997 0892-33 10197<br />

0 1997 <strong>Society</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration<br />

Biased Data Selection in Mars Effect Research<br />

SUITBERT ERTEL<br />

Institut fur Psychologie, Gosslerstr. 14, 37073 Gottingen, Germany<br />

KENNETH IRVING<br />

596 Villa Ave., Staten Island, NY 10302, U.S.A.<br />

Abstract - An earlier study (Ertel, 1988) showed that original evidence <strong>for</strong><br />

Gauquelin's Mars effect with eminent athletes (Gauquelin and Gauqelin 1970)<br />

was based on an incomplete data sample. When athletes initially discarded by<br />

Gauquelin were included the Mars effect declined. The present study bears on a<br />

more subtle effect of the same bias. Gauquelin's original definition of planetary<br />

effects was based on birth frequences obtained in a "narrow" zone of the plan-<br />

et's daily circle (G-sector zone). After accumulating results over decades of<br />

research, he found that the area just preceding his narrow zone indicated initial<br />

planetary effects; he there<strong>for</strong>e proposed to include initial sectors in an "extend-<br />

ed G-sector zone definition. Assuming that these initial G-sectors had been<br />

ignored prior to 1984, the authors suspected that an unbiased proportion of<br />

births <strong>for</strong> these sectors in Gauquelin's exempted data should contrast with the<br />

biased proportion known to exist in the "narrow-zone" sectors. This idea gave<br />

rise to a new bias detector (IMQ, initial vs. main sector quotient), whose validi-<br />

ty was confirmed with the biased Gauquelin data. Selection bias <strong>for</strong> Gauquelin<br />

turned up in his athletes study only; the IMQ did not indicate like anomalies <strong>for</strong><br />

six other professional investigations conducted by Gauquelin.<br />

The IMQ was also applied to three athlete samples collected by skeptic organi-<br />

zations. Among them, the CSICOP data <strong>for</strong> U.S. athletes revealed an anom-<br />

alous IMQ similar to Gauquelin's unpublished athletes. The results there<strong>for</strong>e<br />

suggest that a certain proportion of U.S. athletes with unwelcome positions<br />

might have been exempted from analysis (p = 0.01). Support <strong>for</strong> this suspicion<br />

is provided by complementary evidence indicating biased admissions of less<br />

eminent athletes to the U.S. sample while the preference <strong>for</strong> most eminent ath-<br />

letes was required. Thus an avoidance of G-sector cases, consistent with this<br />

bent, cannot be disavowed. Nevertheless the authors refrain from firm conclu-<br />

sions as this case is circumstantial. It is suggested to merely disregard the CSI-<br />

COP'S negative result of their study in future discussions of the Mars effect as<br />

long as appropriate steps to convincingly resolve remaining ambiguities have<br />

not been not made.<br />

1. Evidence <strong>for</strong> a Mars Effect Despite Biased Sampling<br />

Considerable evidence has been provided in favor of Michel Gauquelin's<br />

claim of a Mars effect (Ertel, 1988, 1992): Gauquelin claimed that athletes were<br />

born more frequently than would be expected by chance with Mars rising above<br />

the earth's horizon or culminating on its daily circle (i.e., when Mars was cross-<br />

1

2 S. Ertel & K. Irving<br />

ing "G-sectors"). Furthermore, he maintained that the percentage of births with<br />

Mars in G-sectors (G%) was more pronounced with eminent than with mediocre<br />

athletes, thus an eminence effect was claimed as a specification of the Mars<br />

effect.<br />

Support <strong>for</strong> the Gauquelin claims resulted when citation counts were intro-<br />

duced as an improved procedure (Ertel, 1988). An athlete's eminence was objec-<br />

tively defined by the number of sports reference sources among a standard set of<br />

such sources (N = 18) in which the athlete was referred to at least once. The<br />

Mars-sports eminence connection attained convincing strength when it was<br />

operationalized in this way by numbers of citations.<br />

These conclusions were confirmed by scrutinizing Gauquelin's unpublished<br />

data. Gauquelin had occasionally referred to his exempting low-eminence ath-<br />

letes from analysis, which is a legitimate procedure in principle, if done without<br />

awareness of planetary positions. Ertel suspected, however, that on occasion<br />

Gauquelin might have been aware of Mars positions when he decided whether<br />

an athlete was or was not eminent enough to be added to the final sample. With<br />

Gauquelin's permission, Ertel searched out and analyzed this unpublished data,<br />

finding that indeed Gauquelin had tended not to exclude marginal athletes from<br />

his high-eminence sample when Mars at their births was in either the rising or<br />

culminating zones. In other words, he tended to rank Mars G-sector cases among<br />

low-eminence athletes more favorably than non-G sector cases.<br />

This can be seen in Figure 1, by first noting that the Mars G% levels of all ath-<br />

letes in Gauquelin's samples (circles and a solid trend line) increase along with<br />

the citation ranks. Gauquelin's unpublished athletes (triangles and the lower<br />

dashed line) are predominantly those with few citations (see the respective num-<br />

bers). This is as it should be, but at the same time the Mars G% levels of unpub-<br />

lished low rank athletes (triangles) are much lower overall than the Mars G% lev-<br />

els of published low-rank athletes (squares), and even at most points below the<br />

line of mean expectancy. This indicates that Gauquelin must have been aware, to<br />

a certain degree, of Mars sector positions when he selected individual cases <strong>for</strong><br />

his sample. Note, however, that when Gauquelin's unpublished cases are added<br />

to the pool of published athletes (solid line), the correlation between eminence<br />

and Mars G% is not diminished as it should have been if the Mars effect were<br />

simply a product of Gauquelin's selection bias. Instead, the correlation increases<br />

(the line becomes steeper) as it should if the effect is genuine. Hence, the idea<br />

that Gauquelin's planetary claim was due to biased selection was clearly refuted.<br />

In what follows, a more subtle effect of Gauquelin's selection bias will be<br />

investigated as it might provide helpful cues at assessing the objectivity of birth<br />

data samples. A new bias indicator (IMQ) is derived and its validity is first tested<br />

with the Gauquelin data as already known to have been influenced by bias. It<br />

will then be applied to other professions <strong>for</strong> which Gauquelin claimed a Mars<br />

effect in order to find out whether his bias affected more of his samples. The bias<br />

probe will also be applied to data collected by organized skeptics who have test-

Fig. 1.<br />

I<br />

~<br />

34 ,<br />

-<br />

Biased Data Selection<br />

Published (N=2888)<br />

3<br />

- Total (N=4391)<br />

-<br />

Eminence rank<br />

G-sector percentages of athletes <strong>for</strong> five citation ranks, separately <strong>for</strong> Gauquelin's<br />

unpublished samples, and total. Absolute frequencies <strong>for</strong> each citation rank.<br />

expectancy <strong>for</strong> Mars is generally abouve (8/36)*(100)= 22.2.<br />

published,<br />

(Chance<br />

CP (Belgian skeptics, Comite Para, 1976), the CSICOP (U.S. skeptics, Kurtz,<br />

Zelen, and Abell, 1979/80), and the CFEPP (French skeptics, CFEPP, 1990).<br />

These studies engendered controversy both inside and outside the organizations<br />

which carried them out (Cuny, 1982; Lippard, 1993; Irving, 1995), and the pos-<br />

sibility of biased data selection was one of several matters at issue. If the IMQ<br />

reliably indicates Gauquelin's selection bias with his unpublished data, then it<br />

might also indicate whether the skeptics' published data suffer from the same<br />

type of deflection.'<br />

2. Defining IMQ, A New Bias Indicator<br />

12 Sector vs. 36 Sector DeBnitions I<br />

For each birth in his sample, Gauquelin determined planetary positions on a ~<br />

scale representing the diurnal circle by 36 sectors. In his first report (Gauquelin,<br />

1955) he generally summed birth frequencies <strong>for</strong> three adjacent sectors resulting<br />

in 3613 = 12 frequencies <strong>for</strong> each sample. In the same publication, he alterna-<br />

tively summed frequencies <strong>for</strong> 18 adjacent sectors (resulting in 18 frequencies),<br />

'The skeptics' data (computer printouts) was kindly provided on request by Professor Jean Dommanget<br />

(CP data in 1986) and by Professor Paul Kurtz (CSICOP data in 1986, CFEPP data in 1994). Analyses of<br />

CSICOP data in chronological order (three successive batches) were provided by D. Rawlins in 1993).<br />

Mars sector positions in these lists were based on the 12 sector scale with decimal precision (range 1-<br />

12.99). CSICOP's sector numbers (S 12') were obtained by rounding decimal values (S 12) down: S 12' =<br />

Int (S12). Trans<strong>for</strong>mation to 36 scale precision was obtained by S36 = Int ((S12)(3)-2)).

4 S. Ertel & K. Irving<br />

but in subsequent publications he generally restricted analysis to 12 units<br />

(Gauquelin, 1960, see Figure 2). The Mars effect was thus defined by significant<br />

deviations from chance of birth frequencies <strong>for</strong> sectors 1 and 4 of the 12-sector<br />

scale. These were labeled "significant" or "sensitive" or "key" sectors.<br />

After three decades of planetary research, Gauquelin, assisted by Thomas<br />

Shanks, who provided programming expertise, subjected his entire data base to<br />

computer calculation, reconsidering the problem of sector zone definition. His<br />

conclusion: "...the two significant zones of the sky.. .begin about 10 degrees<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e the rise or the upper culmination; extend through the ends of sectors 1 and<br />

4 (in the 12 sector mapping) and even slightly beyond, then rapidly lose their<br />

prominence. Since the significant zones somewhat exceed the sector 1 and 4<br />

boundaries, I now speak of 'enlarged key sectors' or 'plus' zones. In the 36-sec-<br />

tor arrangement these comprise four sectors surrounding the rise (nos. 36, 1, 2<br />

and 3) and four at the upper culmination (nos. 9, 10, 11 and 12), respectively"<br />

(Gauquelin, 1988[a], p. 38, citing Gauquelin, 1984). Mean birth frequencies <strong>for</strong><br />

samples <strong>for</strong> which Gauquelin claimed positive planetary effects indeed show that<br />

frequencies of births begin to increase in sectors 36 (preceding the rise of the<br />

planet) and 9 (preceding its culmination) (see Figure 3).2<br />

Terminological changes over several decades of dealing with planetary sectors<br />

("sensitive," "key," "plus" etc.) are likely to cause confusion, so Mueller and<br />

Ertel have suggested "G-sectors" as a standardized label, with "G-percentage"<br />

<strong>for</strong> the percentage of subjects with a given planet in G-sectors and "G-effects"<br />

<strong>for</strong> the general presence of a significant effect involving these sector^.^ Note that<br />

Gauquelin's "enlarged" G-sector calculation deviates from the "narrower" calcu-<br />

lation by simply adding the frequencies <strong>for</strong> the initial sectors no. 36 (preceding<br />

the rise of the planet) and no. 9 (preceding its culmination) to the main sector<br />

frequencies (see Figure 2).<br />

IMQ: The Indicator<br />

At the time the Gauquelin athlete data were published (M. and F Gauquelin,<br />

1970), Gauquelin based G% on the narrow zone, not yet considering the initial<br />

'Even though Gauquelin had surmised that planetary effects <strong>for</strong> professionals might include an area just<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e rise and culmination as early as 1955 (See Gauquelin, 1988b). all work on planetary effects <strong>for</strong> professionals<br />

by Gauquelin was done within the "narrow" 12-sector framework until 1982 (Gauquelin's study<br />

on American data) when he used the extended mode of analysis <strong>for</strong> the first time alongside with his narrow<br />

prcedure. Gauquelin, Michel (1988b). Planetary Heredity. San Diego, CA: ACS Publications, p. 74.<br />

'As the terminology became confusing, I agreed with Mueller (Mueller and Ertel, 1994) - Gauquelin<br />

died in 1991 - to refer to riselculmination zone as "G-zones" irrespective of their precise definition, the<br />

latter may be indicated by subscripts as given by the following examples:<br />

G I : sectors 1 and 4 of Mars' diurnal circle divided into 12 sector units<br />

fMAGl, : frequencies of births <strong>for</strong> Mars summed over ,,GI, sectors<br />

N : the sample's total<br />

MAGIZ% (~MAGIz)/(N) (100)<br />

MAG,, : sectors 36, 1, 2, 3, 9, 10, 11, 12 of Mars' diurnal circle divided 36 units<br />

fMAG,, : frequencies of births <strong>for</strong> Mars summed over MAG36 sectors<br />

N : the sample's total<br />

MAG3h% : (fMAG36)/(N) (loo)

Biased Data Selection<br />

CULYINA~~<br />

Narrow rentltlve zone . Enlarged tensltlve zone<br />

Fig. 2. Two sector divisions <strong>for</strong> the diurnal planetary circle:12 and 36 sectors with "sensitive"<br />

zones. Note that with the 36 sector division, the sensitive zones include "initial" sectors 36<br />

(be<strong>for</strong>e rise) and 9 (be<strong>for</strong>e culmination), which precede the "main" sectors that comprised<br />

the 12-sector division used in Gauguelin's work up until 1984.<br />

Planetary sector<br />

Fig. 3. Mean percent frequencies (a.m.) with standard errors (s.e.) of births across 14 professional<br />

samples <strong>for</strong> 36 planetary sectors (Gauquelin data), the samples being distinguished by sig-<br />

nificant positive planetary effects. Arrows at sectors no. 36 (preceeding rise) and no. 9 (pre-<br />

ceeding culmination) point at regions of rising birth frequencies ("initial" sectors, see<br />

below). Samp1es:Actors (JU), athletes (MA), executives (MA), executives (JU), journalists<br />

(MA), military leaders (MA)(JU), musicians (VE), physicians (MA)(SA), politicians<br />

(MO)(JU), scientists (SA), writers (MO). (MO=Moon, VE=Venus, MA=Mars, JU=Jupiter,<br />

SA=Saturn). Total of percent frequencies across 36 sectors = 100%.

6 S. Ertel & K. Irving<br />

Planetary sector<br />

Fig. 4. Percent birth frequencies of Gauquelin's published (N=2,888) and unpublished (N= 1,053)<br />

athletes across Mars sectors 30 ... 36, 1...15. Arrows point at unbaised frequencies in the<br />

sample, <strong>for</strong> initial sectors only.<br />

Sectors - - - - - . - I<br />

1 pq<br />

CULMIN.<br />

Gauquelin published<br />

N=2,888<br />

Gauquelin unpublished<br />

N=1,053<br />

3619<br />

FEPP<br />

1/10 N=l,076<br />

Birth frequency (%)<br />

Ordinary people<br />

N=13,560<br />

Fig. 5. Concise descriptive results of birth frequencies across initial sectors 36 and 9, and main sec-<br />

tos pairs 1 and 10, 2 and 11, and 3 and 12. Arrows pointing right (e.g. Gauquelin published)<br />

indicate either unbaised selections or baised selections with additive effect on G%. Arrows<br />

pointing left (e.g. Gauquelin unpublished) indicate known or suspected biased selections<br />

with subtractive effects on G%.

Biased Data Selection 7<br />

sectors nos. 36 and 9 of the later, enlarged definition. It is thus reasonable to<br />

assume that while Gauquelin tended to include low-eminence athletes born with<br />

Mars in main sectors in his published sample of champions, he would have treat-<br />

ed low-eminence cases with Mars in initial sectors 36 and 9 in the same way as<br />

he treated low-eminence cases with Mars anywhere else outside the main sectors.<br />

Thus, among his unpublished athletes, initial sector cases would not be deficient.<br />

In Figure 4, birth frequencies of Gauquelin's published and unpublished ath-<br />

letes are compared across sectors 30, 3 1 ... I... 15. For main sectors, the difference<br />

is large, indicating biased selections, while <strong>for</strong> initial sectors there is almost no<br />

difference, as expected, indicating unbiased selections. It may be concluded that<br />

Gauquelin's wished-<strong>for</strong> cases in main sectors 1, 2, 3, 10, 11 and 12 tended to be<br />

admitted to the published sample, even when they were of lesser eminence. On<br />

the other hand, low-eminence cases with Mars in initial sectors 36 and 9, of<br />

whose numerical contribution to the Mars effect Gauquelin was still unaware,<br />

slipped into the unpublished sample as easily as ordinary non-G sector cases.<br />

Initial and main sector results <strong>for</strong> Gauquelin's two samples are summarized by<br />

Figure 5, in the first two sections at the top. Each bar represents percent devia-<br />

tion from expectancy <strong>for</strong> either initial (solid) or main sectors (dashed). An arrow<br />

pointing to the right, as with Gauquelin's published athletes, indicates that birth<br />

frequencies rise from initial to main sectors, which is the direction of change <strong>for</strong><br />

unbiased athletes samples. An arrow pointing to the left, as with Gauquelin's<br />

unpublished athletes, shows that birth frequencies drop from initial to main sec-<br />

tors, indicating a bias effect (i.e., main sector cases have been subtracted while<br />

initial sector cases have been kept in the sample).<br />

Figure 5 also shows the three skeptics' samples underneath the Gauquelin<br />

results. Interestingly, the CSICOP results strongly resemble the result <strong>for</strong><br />

Gauquelin's unpublished athletes (arrow pointing to the left). The CP's and the<br />

CFEPP's samples, on the other hand, do not show the Gauquelin att tern.^<br />

The Gauquelin and CSICOP cases there<strong>for</strong>e deserve more scrutiny. As a quan-<br />

titative indicator <strong>for</strong> possibly biased selections, the "initial vs. main sector quo-<br />

tient," or IMQ, is suggested: It is the ratio between the mean frequency <strong>for</strong> the<br />

initial sectors 36 and 9 (signified by IL) and the mean frequency <strong>for</strong> the main<br />

sectors 1, 2, 3 and 10, 1 1, 12 (denoted collectively by ML). Thus, IMQ = ILIML.<br />

The IMQ under ordinary positive Mars effect conditions, observed in unbiased<br />

data, should be near unity, though generally somewhat less, since birth frequen-<br />

cies <strong>for</strong> initial sector positions do not attain the average frequency level of main<br />

sector positions - the effect is only beginning at that point, and has not yet<br />

reached the peak attained in the main sectors.<br />

How is the IMQ affected by biased selection of data? Gauquelin's published<br />

and unpublished athlete samples serve as examples. If Gauquelin had used noth-<br />

ing but achievement criteria to divide his total sample into eminent (to be ana-<br />

lyzed and published) and less eminent groups (not to be analyzed and not to be<br />

4CP's low initial sector frequency is most probably due to chance, as this deviation can hardly result<br />

from any biased selections (see also Discussion).

Gauquelin's<br />

published data<br />

IMQ-diminished<br />

Effect on G% additive<br />

Total data<br />

Bias removed<br />

No IMQ deviation<br />

S. Ertel & K. Irving<br />

Gauquelin's<br />

unpublished data<br />

IMQ- enhanced<br />

Effect on G% subtractive<br />

IMQ<br />

Fig. 6. Initiallmain sectors qotient (IMQ) <strong>for</strong> Gauquelin's publishedunpublished, and total samples.<br />

0,4 0,6 0,8 1,0 1,2 1,4 1,6 1,8<br />

Mars IMQ<br />

Fig. 7. Mean (=0.95) and confidence limits of IMQ (horizontal axis) <strong>for</strong> samples of varying size<br />

(vertical axis). Various empirical IMQs plotted.

Biased Data Selection 9<br />

published), the IMQs <strong>for</strong> the two subsamples would hardly differ. Apparently,<br />

however, his awareness of Mars sector positions influenced his decision to<br />

include certain low-rank athletes in the eminent (published) subsample and thus<br />

to exclude them from the less eminent (unpublished) subsample. In both cases<br />

the ratio IMQ is affected; it is raised <strong>for</strong> the sample from which he removed<br />

cases, and lowered <strong>for</strong> the sample to which he added cases. This is shown clearly<br />

in Figure 6, in which the IMQ <strong>for</strong> the latter sample (published data, G-cases<br />

added) is 0.83, while the IMQ <strong>for</strong> the <strong>for</strong>mer sample (unpublished data, G-cases<br />

removed) is noticeably high, at 1.3 1. When the two samples are combined, eras-<br />

ing any effect of shifting data from one to the other, the IMQ is 0.95 and no<br />

longer conspicuous.<br />

Figure 5 above has shown that the anomalous pattern of the initial and main<br />

sectors <strong>for</strong> the CSICOP data resembles that of the Gauquelin unpublished sub-<br />

sample. The IMQ <strong>for</strong> the American skeptics' data, is 1.58 which is close to<br />

Gauquelin's IMQ of 1.3 1. Is CSICOP's anomalous IMQ explainable correspond-<br />

ingly? Have cases been eliminated be<strong>for</strong>e the data had been submitted to official<br />

calculation? This would imply that prior knowledge of Mars sector positions had<br />

been obtained. Alternatively, the effect might be explainable by random fluctua-<br />

tions. The question arises which is the more likely explanation, the underlying<br />

error probabilities are thus called <strong>for</strong>.<br />

3. IMQ: Significance Tests<br />

Which variation of IMQ, as shown in Figures 5 and 6, is due to mere chance<br />

and which not? A randomization test <strong>for</strong> the IMQ was devised using control<br />

samples drawn from Gauquelin's ordinary people (N = 13,650), which is lacking<br />

planetary effects and is there<strong>for</strong>e suitable <strong>for</strong> comparison. The test provides esti-<br />

mates of significance (confidence limits) of Mars IMQs <strong>for</strong> all possible sample<br />

sizes between 200 and 4000 cases, at intervals of 50 cases (see Figure 7). For<br />

each sample size N = 200, 250, 300 ... 4000, one thousand samples were drawn at<br />

random from these ordinary people, and IMQs were determined in each case.<br />

Thus <strong>for</strong> each N, 1000 IMQs were obtained and they were rank-ordered<br />

upwards. Ranks 100 and 900 yield confidence limit p = 0.10, ranks 50 and 950<br />

yield p = 0.05, ranks 10 and 990 determine p = 0.01. Figure 7 shows, as it<br />

should, that the distance of confidence lines from the mean (see the vertical line<br />

at IMQ = 0.95) decreases with increasing sample size.<br />

As an example of how the probabilities apply, we determine the IMQ <strong>for</strong><br />

Gauquelin's unpublished sample (N = 1,503 athletes, IMQ = 1.3 1). Is it larger<br />

than what might be expected by chance. We locate the intersection of 1.31 (ver-<br />

tical) and N = 1,503 (horizontal) and find that it lies beyond the confidence line<br />

p = 0.01; thus IMQ <strong>for</strong> Gauquelin's unpublished athletes is p < 0.01.' The IMQ<br />

<strong>for</strong> Gauquelin's published sample is within confidence limits, and the same is<br />

true <strong>for</strong> the IMQ of the CFEPP sample. Only CSCOP's IMQ is significantly<br />

'See Appendix.

10 S. Ertel & K. Irving<br />

greater than expected from randomized controls (p = 0.02). It is also noted that<br />

CP's IMQ deviates from chance expectation (p = 0.01), though in a direction<br />

opposite to CSICOP's, which will be discussed below.<br />

Next, the IMQs of three additional professions were checked <strong>for</strong> which<br />

Gauquelin claimed positive Mars effects (executives, N = 673; military leaders,<br />

N = 3,924; and physicians, N = 3,288). For them, the Mars IMQs as plotted in<br />

Figure 7 fall within the range of what might be expected by chance. Thus<br />

Gauquelin's published executives, military leaders and physicians are apparently<br />

not affected by selection bias in any significant way.6 Two samples collected by<br />

Mueller, German physicians (N = 1,286, Mueller, 1986) and French physicians<br />

(N = 1,083, Mueller and Ertel, 1994) were also subjected to this test: IMQs <strong>for</strong><br />

these samples are not conspicuous either.<br />

4. IMQs and Mars G-Effects Compared<br />

As a side-step improving an understanding of IMQ it was examined whether<br />

the IMQ and G% are correlated, which, given the indications of Figures 5 and 6,<br />

they should be. First the data <strong>for</strong> ordinary people were examined. Since such<br />

data lack planetary effects, and thus any special emphasis on either main or initial<br />

sectors, Mars G% and IMQs <strong>for</strong> ordinary people would be expected to vary<br />

randomly and independently. Birth frequencies <strong>for</strong>, say, sectors 35 and 8 or 1 and<br />

10 are expected to vary across samples of ordinary people no less, and no less<br />

randomly, than sectors 36 and 9.<br />

From Gauquelin's large database samples of 800 ordinary persons were randomly<br />

drawn, 300 times. For each sample we noted G% and the corresponding<br />

IMQ, the results are plotted in Figure 8a. As expected, <strong>for</strong> ordinary people IMQs<br />

vary independently from G%, with Pearson's r = -.04.<br />

By contrast, in samples displaying planetary effects, the IMQs and G% values<br />

should correlate significantly. In the case of positive effects, birth frequencies<br />

begin to rise in sectors 36 and 9 and they continue rising up to the level of the<br />

main G-sectors. The IMQ is there<strong>for</strong>e expected to be 1, representing the downward slopes. The correlation between the Mars IMQs<br />

and G% <strong>for</strong> Gauquelin's, the skeptics', and Mueller's professional samples displaying<br />

positive and negative Mars effects is shown by Figure 8b, based on Table<br />

2, Appendix. As can be seen, IMQs and G% <strong>for</strong> these data sets are highly correlated<br />

(r = -0.77). For CSICOP's data and Gauquelin's unpublished athletes, G%<br />

6The most plausible reason <strong>for</strong> Gauquelin's anomalous IMQs, particularly with athletes, seems to be his<br />

defending the Mars effect against skeptic attacks that focused on athletes only.<br />

'With negative planetary effects, the direction of the relationship reverses, with birth frequencies drop-<br />

ping in sectors 36 and 9 toward the level of the main G-sectors. IMQ in this case is expected to be > 1 and<br />

to increase with increasing planetary effects (G%).

Biased Data Selection<br />

o Random samples (ord. people)<br />

0 ---- Reression (r=-0.04)<br />

0<br />

18 1 I I I I , I I I , I , I<br />

0,4 096 088 190<br />

IMQ<br />

192 1,4 In6<br />

Fig. 8a. IMQ and G% <strong>for</strong> ordinary people, based on 300 samples N = 800 people drawn randomly<br />

from a large database (N = 13,650).<br />

0 Prof. samples<br />

- Regression (r=-0.77)<br />

' " 1 ' 1 ' 1 ' 1 ' 1 ' 1 ' 1 - *<br />

094 096 098 190 192 1 94 196<br />

IMQ<br />

Fig. 8b. IMQ and G% <strong>for</strong> athletes and additional Mars-effect samples, based on Table 2 (Appendix).

12 S. Ertel & K. Irving<br />

is much lower than <strong>for</strong> other samples, and the IMQs are there<strong>for</strong>e inflated even<br />

above the level of samples with unbiased negative Mars effects (musicians, writ-<br />

ers, painters). As already noted, the CP's G% appears larger than other samples<br />

with positive Mars effect. But its IMQ is negatively inflated, opposite in direction<br />

from the CSICOP or Gauquelin's unpublished samples.<br />

5. Discussion<br />

The negative outlier IMQ of the Belgian skeptics (CP) is somewhat puzzling.<br />

Even though the CP has steadfastly defended the integrity of its sample and its<br />

freedom from any possible taint due to Gauquelin's participation 8 Ertel (1995)<br />

had discovered what appeared to be a pro-Gauquelin selection bias in the CP<br />

data (admitting low-eminent G-sector cases).<br />

In fact it had been noted earlier (Ertel (1988) that Gauquelin had assisted this<br />

group in collecting birth data as the author found documents <strong>for</strong> N = 73 cases<br />

excluded from the CP sample in Gauquelin's files in Paris (CP's office is in Brus-<br />

sels). But the known Gauquelin-bias (admitting low eminent G-sector cases),<br />

unquestionably in operation with CP's sample, could merely raise its main G-<br />

sector level. The initial G-sector level should remain untouched; biased selec-<br />

tions of the Gauquelin-type could not depress it (see Figure 5 <strong>for</strong> comparison of<br />

CP with other samples). Likewise, even if Gauquelin had excluded non-G sector<br />

cases from analysis irrespective of eminence criteria - which would imply<br />

fraud - only main G-sector frequencies would have been affected. It is not<br />

immediately clear why such handling of G-sector andlor non-G sector cases<br />

might ever cause an initial sector level to move out of the range of normal varia-<br />

tion.<br />

CP's lack of initial sector frequences might possibly be explained as follows:<br />

Gauquelin, at his speedily screening Mars sectors of CP athletes', might have<br />

separated near-hits (missing the G-zone by one sector) from the rest (clear hits<br />

and misses). He might have done this in order to look up near-hit cases more<br />

carefully later hoping to find among them additional hits. Eventually he might<br />

have joined the subsamples thereby excluding athletes of lesser eminence. At<br />

this moment his reluctance to exclude cases with Mars in G-zones would have<br />

become effective. At his joining of the subsamples, however, while <strong>for</strong>ming a<br />

subsample of exclusions, the subsample of near-hits - small anyway - might<br />

have escaped him, inadvertantly he might have taken it as part of what he was<br />

going to exclude.<br />

'Prof. Dommanget replied (15 March 1993) to Ertel's question concerning Gauquelin's possible influ-<br />

ence on the Committee's data: "I consider it very difficult to fake a material like the one of 535 sports<br />

champions in such a way that this could not be seen. This material has been 'peeled' by us in different<br />

ways when trying to understand the problem and we never observed any indices permitting any suspicion<br />

of falsification. Moreover, all decisions about the material have been taken in common .... Of course, I may<br />

be wrong ...."

Biased Data Selection 13<br />

Is there any evidence <strong>for</strong> this conjecture? If Gauquelin had really behaved that<br />

way we would have to expect that birth frequencies are not only rare <strong>for</strong> initial<br />

sectors 36 and 9 (preceding sector numbers 1, 2, 3 and 10, 1 1, 1 2), but also <strong>for</strong><br />

G-zone-succeeding sectors 4 and 13. Our prediction is testable. A quotient can be<br />

<strong>for</strong>med analogous to IMQ, let us call it SMQ, representing the level of G-zone-<br />

Succeeding sectors: (s4+s 13)/(s 1 +s2+s3+s 10+s 1 1 +s 1 2)/6. In fact, <strong>for</strong> the CP<br />

sample SMQ is conspicuously low (0.71), much lower than <strong>for</strong> the athlete sam-<br />

ples which did not suffer from IMQ-deflections: CFEPP (0.92), GAUQ-<br />

publ.+unpubl.(0.95), lower than <strong>for</strong> the unbiased Mueller samples (PH-German:<br />

0.87, PH-French: 0.96) and lower than <strong>for</strong> the ordinary people's SMQ (1.05).<br />

All Mars SMQ values obtained from 15 available files exceed CP's low level<br />

except the executives' SMQ (sample size N = 673) which is almost at the CP's<br />

level. Admittedly, the present guesswork is somewhat daring, but the available<br />

evidence suggests that CP's IMQ anomaly is not necessarily incomprehensible.<br />

The IMQ <strong>for</strong> the study by the French skeptics (CFEPP) was not conspicuous,<br />

thus giving no indication of a suppression of G-sector cases. This is not to say<br />

that their sample was not biased, however, since an appreciable bent towards<br />

low-eminence admissions has distorted it (Ertel, 1995). Nevertheless, even under<br />

such unfavorable conditions, when the 36-sector division was used, a Mars<br />

effect became manifest. The present results also indicate a positive Mars effect<br />

(see Figure 5), as the deviations of the CFEPP's G-sector frequencies from<br />

chance expectancy resemble the G-sector frequencies obtained from Gauquelin's<br />

published athletes (displaying the Mars effect), they do not resemble those<br />

obtained from ordinary people (not displaying the Mars effect), see bottom graph<br />

in Figure 5.<br />

The IMQ <strong>for</strong> the U.S. skeptics (CSICOP) appears anomalous. It deviates from<br />

expectancy in a way as was found with Gauquelin's problem data. The pattern of<br />

their initial and main G-sectors, as shown in Figure 5, fits the pattern of<br />

Gauquelin's unpublished athletes, and their IMQ of 1.58 is equally significant.<br />

Regarding Gauquelin's IMQ, there is no doubt that it indicates selection bias,<br />

considering Ertel's (1988) independent evidence. Selection bias of a similar<br />

nature should thus be considered as a possible explanation <strong>for</strong> CSICOP's IMQ.<br />

Is independent evidence here also a~ailable?~<br />

In fact it is. Additional support <strong>for</strong> an understanding of the CSICOP's anomaly<br />

in terms of bias is obtained in view of an observation connected with CSICOP's<br />

collecting the data in three successive canvasses, with sector calculations run <strong>for</strong><br />

each batch be<strong>for</strong>e the next was gathered. This procedure was criticized <strong>for</strong> possi-<br />

ble feedback effects in the commentaries that followed publication of the study<br />

(e.g. Rawlins, 1981 ; Curry, 1982), and statistical evidence <strong>for</strong> such effects has<br />

now been established. Figure 9a shows that in the CSICOP study the eminence<br />

criteria appear to have been lowered from one batch to the next. This judgment is<br />

backed by independent evidence from citation counts, as G-percentages <strong>for</strong> suc-<br />

cessive batches declined in lock step with eminence levels (see Ertel, 1995, Fig-<br />

ure 9b) (a scrutiny of this effect has been provided by Ertel, 1995).

S. Ertel & K. Irving<br />

1 2 3<br />

Canvass no.<br />

Fig. 9a. Declining eminence levels <strong>for</strong> CSICOP's three successive canvasses.<br />

25<br />

20:<br />

15:<br />

1<br />

-<br />

-.-<br />

T<br />

Chance expectaricy<br />

1 2 3<br />

Canvass no.<br />

Fig. 9b. Declining Mars effect indications (G%) <strong>for</strong> CSICOP's three canvasses.<br />

1

Biased Data Selection 15<br />

Thus, the evideilce, obtained by both, eyewitness of <strong>for</strong>mer reseachers and<br />

present statistical analysis, betrays an increasing eminence loss across batches. If<br />

CSICOP's IMQ is truly indicative of biased selections one would expect that<br />

their IMQ should rise correspondingly from one canvass to the next. The data are<br />

consequent with this expectation (see Table 3, Appendix), as the IMQ rises<br />

sharply across batches. That is, the level of the main sectors drops, while the<br />

level of the initial sectors remains constant. Looking at the error probabilities<br />

illustrated in Figure 7, we find the IMQs <strong>for</strong> the first canvass to be within normal<br />

range, while the IMQs <strong>for</strong> the second and third canvasses combined (N = 280), at<br />

1.52, deviate at the 0.05 level.''<br />

The above argument implies that the two types of bias, G-sector avoidance<br />

and low-eminence admission, must be properly distinguished. Only G-sector<br />

avoidance affects the IMQ, due to the discrepancy between the untouched initial<br />

sector frequencies and the altered main sector frequencies. By contrast, low-emi-<br />

nence admission by itself will not affect the IMQ, since admitting less eminent<br />

athletes lowers frequencies in both the extended and narrow sectors equally -<br />

that is to say, the effect is fairly distributed across all 8 sectors involved. Unques-<br />

tionably, as was shown in Ertel, 1995, CSICOP's sample has been affected by a<br />

low-eminence bias, as shown in Figure 9a and 9b. The evidence of our present<br />

study suggests that their sample might suffer in addition from effects by G-sector<br />

avoidance.<br />

But is the evidence compelling? Combining the significance levels of our two<br />

independent indicators, IMQ (p = 0.02), and its rise over three successive can-<br />

'Rawlins (1979) explicitly addressed questions about the CSICOP sample, saying that "I vainly urged<br />

that the rest of CSICOP also stay out of sampling, as a matter of policy. However, since some have<br />

expressed suspicions regarding the fairness in this instance, I am bound to state that 1 (more than anyone)<br />

can vouch <strong>for</strong> the fact that Kurtz's selection was unbiased. To fudge the sample, one must correctly pre-<br />

compute celestial position, but Kurtz, Zelen, and Abell never did accomplish this be<strong>for</strong>e the samples were<br />

finally turned over to me and the solutions given to them." However, as the above-mentioned researchers<br />

themselves point out (Kurtz, Zelen, Abell, 1979), the Gauquelin sections are "similar to the 'Placidean'<br />

houses" which means they are easily approximated with standard horoscopes widely available from com-<br />

puter calculation services <strong>for</strong> a nominal fee. This is only to point out that the potential problems denied by<br />

Rawlins and alleged by others are within the realm of possibility, not to state that they are fact. As <strong>for</strong><br />

"neutral researchers" Frank Dolce and Germaine Harnden, who were said to have made the "actual selec-<br />

tion" of the data in order to "avoid any bias by Kurtz, Zelen, and Abell" (Kurtz, Zelen, Abell, 1979),<br />

despite this statement, their role in the experiment is decidedly unclear, particularly with respect to who con-<br />

trolled the process of monitoring the responses to requests <strong>for</strong> birth data from various states and <strong>for</strong>warding<br />

it to Rawlins. No account which details either of these two crucial steps mentions either Hamden or Dolce<br />

as having been involved in them. See Curry (1962) and Rawlins (1981).<br />

'@Though only Dennis Rawlins, member of the CSICOP research team, apparently had the expertise to<br />

do the astronomical computer calculations and he, by his own choice, had no part in the sampling process,<br />

this does not exclude the possibility that researchers in charge of data selection obtained Mars sector posi-<br />

tions independently. Since the Gauquelin "sectors are roughly equivalent to the 9th and 12th houses of a<br />

standard horoscope using Placidus houses (Jerome, 1975), any birth <strong>for</strong> which the horoscope shows Mars in<br />

one of these houses will likely have Mars in a key sector. No expertise is required to obtain such horoscopes.<br />

As one example, widely-advertised computer calculation services have offered batch calculations of such<br />

horoscopes <strong>for</strong> nominal sums since the early 1970s, and all that is required to use them is the raw data. Dis-<br />

cussion of the relation of Placidus houses to Gauquelin sectors is found at several points in the extensive lit-<br />

erature on CSICOP and the Mars effect, so knowledge of the relation between the two was available to all<br />

principals.

16 S. Ertel & K. Irving<br />

vasses (p = 0.05), yields p = 0.01. For ordinary research, effects associated with<br />

this level of error probability are conventionally considered as "very significant."<br />

However, in the present case we expressly abstain from any firm interpretation of<br />

this finding. After all, an error probability of p = .O1 does not exclude error. Even<br />

though G-sector avoidance would fit as just another aspect of the conspicious<br />

drop of G-sector frequencies from one batch to the next the anomalous IMQ<br />

might be <strong>for</strong>tuitous.<br />

Only one conclusion appears unavoidable: CSICOP's alleged negative evi-<br />

dence <strong>for</strong> a Mars effect must hence<strong>for</strong>th be disregarded unless the CSICOP<br />

would prove that a chance interpretation of the present IMQ-finding has in fact<br />

no alternative. For example, the CSICOP might invite critical non-CSICOP<br />

researchers to check their original lists of data and their correspondence with<br />

birth registry offices. This would be in keeping with the open files policy fol-<br />

lowed by Gauquelin, and also consequent with the CSICOP's own generously<br />

providing their data in the past to critical researchers. Alternative ways of prov-<br />

ing the integrity of CSICOP's data are hardly conceivable, but if convincing,<br />

might certainly be accepted.<br />

Disclosures of retarding episodes obtained by probes into past research are less<br />

urgent than is the advancement of our understanding of the planetary effects in<br />

future perspective. If nothing else, the IMQ has added another element to the<br />

evidence of Gauquelin's findings, a seemingly small one, but powerful enough to<br />

reveal at one blow the discoverer's personal weakness as well as the strength of<br />

his discovery.<br />

Acknowledgment<br />

We received helpful comments on the first draft of this paper from Geoffrey<br />

Dean, David Valentiner, and Mark Urban-Lurain.<br />

Appendix: Further Explanation of IMQ<br />

Gauquelin's published sample of (N = 2,888) is biased by individual selections<br />

favoring a Mars effect, since cases born with Mars in main G-sectors tended to<br />

be included. We there<strong>for</strong>e expect an IMQ smaller than chance level. The effect<br />

<strong>for</strong> the published sample, however, should be numerically smaller than that <strong>for</strong><br />

the unpublished sample, considering the greater size of the published compared<br />

to the unpublished sample. The logic will become clear through the examples in<br />

Table 1.<br />

An athletes' sample may have, say, 720 cases, 20 cases in each of 36 Mars<br />

sectors. So 20 cases are assumed to be born with Mars in each of 8 G-sectors<br />

(<strong>for</strong> sector numbers, see first row). We may divide the total equally into two<br />

subsamples (PUB and U-PUB) in such a way that each subsamples has 10 cases<br />

in each G-sector (second row). IMQs <strong>for</strong> PUB or U-PUB are there<strong>for</strong>e<br />

( lo)/) 10+ 10+ 10)/3 = 1.0 (see last column). We now simulate biased selections<br />

such that each main G-sector of the U-PUB sample obtains 8 instead of 10 cases

Biased Data Selection 17<br />

(third row, IMQ = 1.25). In this instance the published counterpart sample<br />

PUB(1) gets 12 G-sector cases instead of 10 (fourth row, IMQ = 0.83).<br />

Suppose the original sample has 30 cases with Mars in each G-sector and our<br />

dividing the total allocates 10 cases to U-PUB and 20 cases to PUB. In that<br />

case, biased allocation to U-PUB as shown in the third row would give rise to<br />

TABLE 1<br />

Effects on IMQs by Biased Sampling <strong>for</strong> Fictive Samples<br />

I M M M I M M M<br />

I sectors 36 1 2 3 9 10 11 12 IMQ<br />

2 PUB & U-PUB 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 1.0<br />

3 U-PUB 10 8 8 8 10 8 8 8 1.25<br />

4 PUB (1) 10 12 I2 12 12 12 12 12 0.83<br />

5 PUB (2) 20 22 22 22 20 20 20 20 0.91<br />

I: initial G-sector<br />

M: main G-sector<br />

CFEPP<br />

CP<br />

CSICOP<br />

EX<br />

MI<br />

MU<br />

SP (Pub)<br />

SP (Upub)<br />

PA<br />

PH<br />

PH(D)<br />

PH(F)<br />

WR<br />

TABLE 2<br />

Mars G-Sector Percentages<br />

Profession Source N PI^ G% IMQ<br />

Athletes, French<br />

Athletes, Belg./Fr.<br />

Athletes, U.S.A.<br />

Executives<br />

Milit. Leaders<br />

Musicians<br />

Athletes, Publ.<br />

Ahtletes, Unpubl.<br />

Painters<br />

Physicians<br />

Physicians, German<br />

Physicians, French<br />

Writers<br />

CFEPP<br />

CP<br />

CSICOP<br />

Gauq.<br />

Gauq.<br />

Gauq.<br />

Gauq.<br />

Gauq.<br />

Gauq.<br />

Gauq.<br />

Muel.<br />

Muel.<br />

Gauq.<br />

pos<br />

pos<br />

-<br />

pos<br />

PO s<br />

neg<br />

PO s<br />

-<br />

neg<br />

PO s<br />

POS<br />

PO s<br />

neg<br />

(G%) direction of Mars effect, (poslneg), and initiallmain sector quotient (IMQ) <strong>for</strong> athletes and<br />

additional samples.<br />

TABLE 3<br />

IMQs <strong>for</strong> CSICOP's Three Canvasses Separately and Total (cd. Figs. 9a & 9b)<br />

Canvass: I st 2nd 3rd Total<br />

N 128 198 82 408<br />

f(I) 6 16 7 29<br />

f(M) 25 24 6 5 5<br />

MQ 0.72 2.00 3.50 1.58<br />

f(1) frequencies of births <strong>for</strong> initial sectors 36,9 f(M) frequencies of births <strong>for</strong> main sectors 1,2, 3,<br />

10, 1 1, 12. Example <strong>for</strong> IMQ calculation, 2nd canvass: (1 6/2)/(24/6)= 2.00.<br />

I

18 S. Ertel & K. Irving<br />

biased allocations <strong>for</strong> PUB(2) is 0.91, and the distortion of IMQ <strong>for</strong> PUB (2) is<br />

thus numerically smaller than IMQ <strong>for</strong> PUB ( 1).<br />

Gauquelin's published sample is almost twice as large as Gauquelin's unpub-<br />

lished sample, so its IMQ (= 0.87) deviates less from expectation (which is < 1<br />

anyway) than the IMQ of the unpublished sample, IMQ = 0.87 is, <strong>for</strong> that rea-<br />

son, not significant, as Figure 7 shows.<br />

References<br />

CFEPP (1990). VCrification de l'effet Mars. Etat de 17expCrience au 20 juin 1990. Unpublished<br />

Research Report.<br />

ComitC Belge pour 1'Etude des PhCnom&nes RCputCs Paranormaux (1976). ConsidCrations critiques<br />

sur une recherche faite par M. M. Gauquelin dans le domain des influences planktaires. Nouvelles<br />

Bre'ves, 43,327.<br />

Curry, P. (1982). Research on the Mars effect. Zetetic Scholar, 9, 34.<br />

Ertel, S. (1988). Raising the hurdle <strong>for</strong> the athletes' Mars effect. Association co-varies with eminence.<br />

Journal of <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration, 2, 1, 53.<br />

Ertel, S. (1992). Update on the Mars effect. The Skeptical Inquirer, 16, 2, Winter, 150.<br />

Ertel, S. (1995). Mars effect uncovered in French skeptics' data. Correlation, 13,2, 3.<br />

Gauquelin, M. (1955). L'influence des Astres. ~tude Critique et Expe'rimentale. Paris: Le Dauphin.<br />

Gauquelin, M. (1960). Les Hommes et les Astres. Paris: Denoel.<br />

Gauquelin, M. (1 983). Kosmische EinJEisse auf Menschliches Verhalten. (German translation of<br />

[Cosmic influences on human behavior], London: Futura, 1976). Freiburg i. Br.: Bauer.<br />

(Reprinted: 1 988).<br />

Gauquelin, M. (1984). Profession and heredity experiments: Computer reanalysis and new investigations<br />

on the same material. Correlation, 4, 1, 8.<br />

Gauquelin, M. (1988a). Is there a Mars effect? Journal of <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration, 2, 1,29.<br />

Gauquelin, M. (1988b). Planetaty Heredity. ACS Publications. San Diego.<br />

Hoebens, P. H. (1982). Comments on "Research on the Mars effect" by Patrick Curry. Zetetic Scholar,<br />

10,70.<br />

Irving, K. (1995). The Mars effect controversy. In: S. Ertel, T. and K. Irving, The Tenacious Mars<br />

Effect. London: Urania.<br />

Kammann, R. (1982). The true believers: Mars effect drives skeptics to irrationality. Zetetic Scholar,<br />

10, 50.<br />

Kurtz, P., Zelen, M., and Abell, G. 0. (1979180 b). Results of the US test of the "Mars effect" are<br />

negative. The Skeptical Inquirer, 4,2, 19.<br />

Lippard, J. J. (1993). 'Mars effect chronology,' 22 January 1993. Unpublished draft.<br />

Miiller, A. (1986). LaBt sich der Gauquelin-Effekt bestatigen? Untersuchungsergebnisse mit einer<br />

Stichprobe von 1288 heworragenden krzten. Zeitschrift fur Parapsychologie und Grenzgebiete<br />

der Psychologie, 28, 87.<br />

Miiller, A., and Ertel, S. (1994). 1,083 members of the French "AcadCmie de MCdecine." Astro-<br />

Forschungs-Data, Vol. 5. Waldmohr: A. P. Miiller.<br />

Rawlins, D. (1981). Starbaby. Fate, 34, 10, 1.

Journal of Scientijic Exploration, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 19-39, 1997 0892-33 10197<br />

O 1997 <strong>Society</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Scientific</strong> Exploration<br />

Is the "Mars Effect" Genuine?<br />

PAUL KURTZ, JAN WILLEM NIENHUYS, RANJIT SANDHU<br />

State University ofNew York, c/o PO Box 32, BufSalo, NY 14215<br />

Abstract - Gauquelin claimed that there is a statistically significant correlation<br />

between the positions of Mars and the times and places of birth of sports cham-<br />

pions. Independent scientists have attempted to replicate this hypothesis without<br />

success. We provide a brief history: the Cornit6 Para, the Zelen and U.S. tests,<br />

and a recent French test. Ertel and Irving, in sifting through the data, attempt to<br />

rescue Gauquelin's thesis. Ertel introduced his "eminence test", and Ertel and<br />

Irving their "IMQ bias indicator." However, they presuppose what they set out<br />

to prove. We conclude that there is insufficient evidence <strong>for</strong> the "Mars effect",<br />

and that this effect may be attributed to Gauquelin's selective bias in either dis-<br />

carding or adding data post hoc.<br />

Gauquelin's Claim<br />

French psychologist and writer Michel Gauquelin, in collaboration with his wife,<br />

Frangoise Schneider-Gauquelin, wrote that although classical astrology was mis-<br />

taken, there were "astrobiological" or "cosmobiological" correlations between<br />

planetary positions and birth times on the one hand and personality traits and<br />

professional achievements on the other - between Jupiter and military men,<br />

Saturn and scientists, Mars and sports champions, etc.<br />

The planet Mars rises and sets just like any other celestial phenomenon. Mr.<br />

and Mrs. Gauquelin divide the time between rising and setting into six equal<br />

intervals, numbered 1 through 6. Likewise, they divide the time between setting<br />

and rising into another six equal intervals, numbered 7 through 12. These sectors<br />

coincide with one of a dozen or so popular astrological house systems, namely<br />

that of Placidus, though the Placidean numbering is different.<br />

The Gauquelins suggested that sports champions were somewhat more likely<br />

to be born when Mars is passing through the first sector (approximately the first<br />

two hours after the rise of Mars) and the fourth sector (roughly the two hours<br />

after culmination). Interestingly, in the traditional astrology of Ptolemy (Tetra-<br />

biblos), the two most important points in the house divisions are the Ascendant<br />

("oroscopos") and the Midheaven or Medium Celi - which are the initial<br />

boundaries of the Gauquelins' sectors 1 and 4.<br />

It would appear that the chance of being born in either the first or fourth sec-<br />

tors is 2 out of 12, or 16.67%. A small adjustment is necessary, however, to take<br />

two factors into account: (1) the astronomic factor, namely the positions of Mars<br />

as seen from Earth, or more specifically from the latitude of France, and (2) the<br />

demographic factor, namely the daily pattern of births (more in the early morn-

20 Kurtz et al.<br />

ing, fewer in the evening). This adjustment has been estimated at about 0.5%,<br />

making the chance expectation 17.17% (Rawlins, 1979-80, p. 30). Sports cham-<br />

pions, said Gauquelin, were born in the first and fourth sectors about 22% (more<br />

exactly, 452 in 2,088, or 21.65%) of the time. The deviation was too small to be<br />

of any practical use. One must meticulously collect hundreds of cases to observe<br />

it at all. Yet if Gauquelin was correct, the deviation was theoretically interesting.'<br />

Michel Gauquelin collected champions' names from sports directories, and<br />

then tried to locate their actual birth data in the town registries. In support of his<br />

claim, he published in 1955 a total of 567 French champions with their names<br />

and birth data (plus one erroneous name) (Gauquelin, 1955). In 1960 he reported<br />

915 additional <strong>for</strong>eign champions, together with 717 "less well known" sports<br />

people that served as a control, but without specific names and data (Gauquelin<br />

1 960).<br />

He added further data to his files from a replication by the Belgian ComitC<br />

Para (more on this below). With Gauquelin's help, the ComitC Para derived a<br />

sample of sports champions, which by 1968 produced 330 new names (mostly of<br />

French champions).<br />

Gauquelin added another 276 names (among whom were 113 aviators and 76<br />

rugby players) to his total sample, to yield 2,088 "well-known" champions<br />

(Gauquelin, 1970). Meanwhile he collected piecemeal another 278 "lesser"<br />

champions be<strong>for</strong>e 1976. We mention this, because in the discussions Michel<br />

Gauquelin and others have stated several times that the 2,088 consisted of 1,553<br />

champions collected first, followed by the ComitC Para test of 535 champion^.^<br />

The Test by the Belgian Cornit6 Para<br />

As mentioned above, the Belgian Comiti Para, beginning in 1967, attempted<br />

to test Gauquelin's thesis. Their 535 champions consisted of 205 already in<br />

Gauquelin's 1955 book (it was thus not an entirely fresh sample) and 330 "new"<br />

ones. In 1976 the Comiti Para published its final report (1976), and found that<br />

22.2% of these sports champions were born with Mars in sectors 1 or 4. (We<br />

shall hereafter refer to the percentage born with Mars in sectors 1 and 4 as the<br />

Mars percentage.) The Comite Para maintained, however, that Gauquelin's theo-<br />

retical expectation (of about 17 percent) was not computed correctly. There was<br />

thus some dispute between the ComitC Para and Gauquelin about whether the<br />

test constituted a replication. The ComitC Para thought that demographic factors<br />

-- -- --<br />

'A sympathetic account of the Gauquelins' studies can be found in Eysenck and Nias (1982,<br />

pp. 182-209), and interested readers are encouraged to consult this source. Though the two authors were<br />

favorable to the Gauquelins' hypotheses, we believe that they might modify their views were they to exam-<br />

ine the recent research and findings, which we summarize below.<br />

2For example, in "The Truth about the Mars Effect on Sports Champions" (M. and E Gauquelin 1976)<br />

the Gauquelins refer to "the committee's results <strong>for</strong> 535 sports champions ... our <strong>for</strong>mer results <strong>for</strong> the group<br />

of 1,553 other champions." In the next issue of The Humanist (Abell and Gauquelin 1976, p. 40) this<br />

evolved into 1,553 champions from the 1960 publication and a separate sample of 535 m&ng a total of<br />

2,088. M. and F. Gauquelin (1977) refer in their report on the Zelen test to "our first group of 1,553" and<br />

"the Cornit6 Para's group of 535," and in 1979 they distinguish "the effect observed by the Belgian Cornit6<br />

Para (22.2 percent) and by us (21.4 percent)," ie. 119 in 535 and 333 in 1,553. (See also Gauquelin, 1978.)

Mars Effect 21<br />

were not properly taken into account: the births of the athletes were not uni<strong>for</strong>m-<br />

ly distributed in the time-period studied (1872-1945), and the daily patterns of<br />

births varied during this period. Gauquelin insisted that the Comit6 Para's test<br />

had confirmed his hypothesis. The Comit6 Para denied it.<br />

Gauquelin had helped to supply the data <strong>for</strong> the test of the Comit6 Para. How-<br />

ever, the circumstances surrounding the data compilation of the test are most<br />

unclear. Ertel (1988) claims that the 332 "new" champions of the Para test (a<br />

counting error; it should be 330) had already been collected by Gauquelin in<br />

1962, along with 76 Belgian soccer players that had not been used in the Para<br />

test. Luc de Mart-6 states that at the meeting between Gauquelin and the Comitk<br />

Para in 1967 the list of 535 names was already decided upon (Ertel & Irving,<br />

1996, pp. SE-18, 19, and 50). This claim is hardly credible; it presupposes that<br />

the Comitk Para was clairvoyant and knew in advance the precise number of<br />

champions about whom they would receive in<strong>for</strong>mation from town halls. The<br />

Comitk Para collected 430 French champions from their main source book, but<br />

Professor J. Dommanget has provided documents indicating that data of 589<br />

champions from this book were requested.<br />

Concerning the Belgian soccer players, it was decided to select only the 43<br />

who had been chosen to defend the glory of Belgium at least 20 times. It is<br />

unknown how that decision was arrived at and if any prior knowledge of the<br />

Mars effect among Belgian soccer players played a role in that decision. If<br />

Ertel's in<strong>for</strong>mation about the year 1962 is accurate then Gauquelin knew already<br />

the Mars positions of 119 Belgian soccer players when the decision about the<br />

cut-off at 20 was taken. We do know that above that cut-off the Mars percentage<br />

happens to be 21% and below that line it is only 12%.<br />

We think there is sufficient reason to reject the result of the Para test. There are<br />

too many doubts surrounding the process of data gathering.<br />

The "Zelen Test"<br />

The dispute between Gauquelin and the Cornit6 Para concerned the expected<br />

"Mars percentage" <strong>for</strong> the general population. Marvin Zelen, then a professor of<br />

statistics at State University of New York, now at Harvard, proposed a test of the<br />

baseline percentage. This became known as the "Zelen test," and it was devel-<br />

oped in cooperation with astronomer George Abell and Paul Kurtz. Zelen recom-<br />

mended Gauquelin randomly draw 100 or 200 names from his sample of cham-<br />

pions,3 and then compare their Mars sectors with all other births occurring at the<br />

same times and places (Zelen, 1976). Zelen designed this test to help determine<br />

the baseline Mars percentage, and also to control <strong>for</strong> various other demographic<br />

aspects that had so far not been a matter of dispute.<br />

Michel and Fran~oise Gauquelin assembled birth data on 16,756 ordinary per-<br />

sons born at about the same times and places as a subsample of 303 champions.<br />

- - - --- -- -- --- -- -<br />

3Zelen specifically referred to "Gauquelin's sample of 1,553 sports champions." Apparently Zelen had<br />

been led to believe that there was a neat batch of pre-Comitt Para champions that could be used to generate<br />

a null-hypothesis <strong>for</strong> the new batch of Comitk Para-champions.

22 Kurtz et al.<br />

They observed that the Zelen method yielded a theoretical prediction of 51.4<br />

births in sectors 1 and 4 among the 303, i.e. 16.96%. More precisely, this result<br />

means that the "true" percentage is between 16.4% and 17.5% (95% confidence<br />

limits) and that there is no reason to suppose that the astrodemographic correc-<br />

tion should vastly exceed 0.5%. There was again some dispute as to the validity<br />

of the test, particularly since the Gauquelins did not follow Zelen's original pro-<br />

tocol (Zelen et al., 1977). For example, Gauquelin did not draw the names ran-<br />

domly. His total sample of 2,088 champions included 42 Parisian athletes, and<br />

he included all 42 in his subsample of 303. He selected the remaining champions<br />

from those who had been born in capitals of Departments of France or Provinces<br />

of Belgium.<br />

The Gauquelins also chose the matching non-champions in Paris from only<br />