Absolute Sound

Absolute Sound

Absolute Sound

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

85<br />

65<br />

22<br />

IN THIS ISSUE<br />

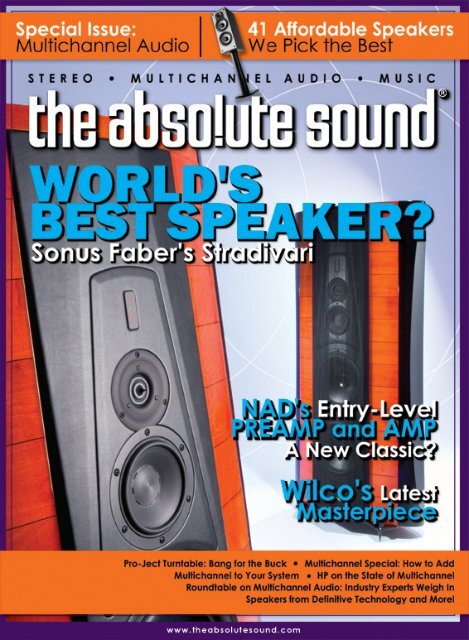

ISSUE 148 ■ JUNE/JULY 2004<br />

103 Cover Story:<br />

Drop-Dead Gorgeous: Sonus Faber<br />

Stradivari “Homage” Loudspeaker<br />

In sound and looks Sonus Faber’s new statement design is simply<br />

gorgeous, so says our man, Jonathan Valin.<br />

36 Recommended Products<br />

Loudspeakers Under $5000<br />

Our staff selects the crème de la crème in affordable and mid-priced speakers.<br />

77 The State of Multichannel Audio<br />

In a series of special reports in The Cutting Edge, we explore the past,<br />

present, and potential future of high-end multichannel sound. In his<br />

Multichannel Audio Primer, Robert Harley explains the ins and outs of<br />

expanding your two-channel system—the right way; the TAS<br />

Roundtable finds RH, HP, Classical Music Editor Andy Quint, and<br />

recording engineer Peter McGrath debating the pros and cons of stereo,<br />

multichannel, center-channel speakers, and subwoofers; and in his<br />

Workshop, HP looks at the Dark Side of Multichannel <strong>Sound</strong>.<br />

Equipment Reports<br />

56 NAD C 162 PREAMPLIFIER, C 272 POWER AMPLIFIER<br />

Chris Martens reports on NAD’s new entry-level separates.<br />

62 YBA INTÉGRÉ INTEGRATED AMPLIFIER<br />

The latest combo amp from YBA finds Neil Gader waxing nostalgic.<br />

65 DOUBLE-DIPPING: MOREL OCTWIN 5.2M LOUDSPEAKER<br />

Neil Gader listens to a stacked pair of speakers with more than a few<br />

sonic and design twists.<br />

68 FURTHER THOUGHTS: THE GAMUT D 200 MK3<br />

Jonathan Valin reports on the latest incarnation of a technological<br />

tour-de-force.<br />

72 ROMANTIC AT HEART—VALVE AMPLIFICATION COMPANY AVATAR SUPER<br />

INTEGRATED AMPLIFIER<br />

Wayne Garcia on VAC’s top-of-the-line, retro-looking, all-tube integrated amp.<br />

Viewpoints<br />

4 FROM THE EDITOR<br />

6 LETTERS<br />

121 MANUFACTURER COMMENTS<br />

2 22 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

Columns<br />

16 INDUSTRY NEWS<br />

20 FUTURE TAS<br />

Hot new products on the horizon.<br />

22 START ME UP: Meeting High-End Expectations on a Modest Budget<br />

Our column on affordable gear resumes with new writer Jerry Sommers.<br />

28 ABSOLUTE ANALOG<br />

Paul Seydor spins Pro-Ject’s RM 9 turntable and Sumiko’s Blackbird<br />

cartridge, and sets it all atop Townshend’s Seismic Sink Isolation Platform.<br />

TAS Journal<br />

33 EDITORIAL: Missing the Boat<br />

Robert Harley argues that, for all the great contributions the high end<br />

has made over the years, it also has a habit of ignoring opportunities to<br />

expand its business (and your options).<br />

48 BASIC REPERTOIRE: The Piano Trio<br />

Andrew Quint kicks off the first in a new series on must-own music.<br />

Music<br />

127 ROCK AND POP RECORDING OF THE ISSUE Wilco: A ghost is born;<br />

Franz Ferdinand: Franz Ferdinand; Sigur Ros: Ba Ba Ti Ki Di Do;<br />

Broken Social Scene: Bee Hives; Sam Phillips: A Boot and a Shoe;<br />

Patti Smith: Trampin’; Eric Clapton: Me & Mr. Johnson and Keb Mo: Keep It<br />

Simple; Diverse: One A.M. and Kanye West: The College Dropout; Lou Reed:<br />

Animal Serenade, Allman Brothers: One Way Out, and Bob Dylan: The<br />

Bootleg Series Volume 6; Ellis Hooks: Uncomplicated; The Buzzcocks: Singles<br />

Going Steady and The Saints: I’m Stranded (Runt 180-gram LPs)<br />

SACD —Mission of Burma: ONoffON; George Harrison: Live In Japan<br />

141 JAZZ Ted Sirota’s Rebel Souls: Breeding Resistance and Chicago<br />

Underground Trio: Slon; Duke Ellington: Masterpieces by Ellington; Brad<br />

Mehldau: Anything Goes and Joel Framm with Brad Mehldau: Don’t<br />

Explain; Fred Hersch: Trio + 2; Jason Lindner: Live/UK; Miguel Zenón:<br />

Ceremonial; Andy Bey: American Song<br />

SACD—Great Jazz Trio: Someday My Prince Will Come<br />

149 CLASSICAL Purcell: Dido and Aeneas and Britten: The Turn of the Screw;<br />

Anonymous 4: American Angels and Trio Mediaeval: Soir Dit-Elle; The<br />

1950s Haydn Symphonies Recordings; Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5<br />

SACD—Bartók: The Miraculous Mandarin and Bluebeard’s Castle;<br />

Mahler: Symphony No. 3; Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition and<br />

Prokofiev: Ivan the Terrible; SACD and DVD-A Tackle Beethoven’s Nine<br />

Symphonies Conducted by Karajan and Abbado<br />

158 ABSOLUTE AUDIOPHILIA<br />

Mendelssohn: Symphony No. 3 (Maag) (Speakers Corner 45 RPM LPs);<br />

John Lennon: Imagine and Aimee Mann: Lost In Space (MoFi 180-gram LPs)<br />

160 TAS Retrospective<br />

NAD 3020: The Little Amp That Put High-End <strong>Sound</strong> Within<br />

Everyone’s Reach<br />

Chris Martens<br />

WWW.THEABSOLUTESOUND.COM 3<br />

103<br />

28<br />

127

f r o m t h e e d i t o r<br />

There’s a certain cynicism among a minority of audio-magazine readers<br />

regarding the integrity of the review process. This view, sometimes<br />

expressed on Internet forums, goes something like this: because<br />

reviewers enjoy the use of expensive equipment without paying for it,<br />

there’s a quid pro quo with the manufacturer that guarantees a favorable<br />

review. Those holding this belief mention this alleged arrangement casually, as<br />

though corruption were an automatic and integral aspect of magazine reviewing<br />

that everyone knows about and tacitly accepts.<br />

When I come across such comments, I don’t know whether to laugh or be outraged.<br />

Those holding such views have absolutely no basis for their position except<br />

an a priori assumption that something untoward must be going on. As someone who<br />

has written more than 350 product reviews, and presided as editor over the publication<br />

of another 400 or so, I’d like to share my experience, as well as outline The<br />

<strong>Absolute</strong> <strong>Sound</strong>’s policies regarding equipment loans.<br />

In my eleven years as a full-time reviewer and four years as Editor (two-and-ahalf<br />

years at TAS), I have never been approached by a manufacturer offering equipment,<br />

long-term loans of equipment, or any other compensation for favorable coverage.<br />

It just doesn’t happen. If such a practice existed, I think I’d be aware of it considering<br />

the large number of products I’ve reviewed over the past fifteen years. Of<br />

course, I can’t speak for other reviewers or publications, but this is my experience.<br />

The cynics may respond that even if there’s no overt quid pro quo, a favorable review<br />

makes the manufacturer amenable to a long-term loan of the product, and thus influences<br />

the reviewer. The reality is that I could spend an afternoon on the phone and<br />

assemble a reference-quality system of components on long-term loan—components<br />

entirely of my choosing, before a word was written, and with no promise of a favorable<br />

review. If virtually all products are available on long-term loan, how can there be any<br />

coercion by a single manufacturer to write a favorable review?<br />

But are long-term loans ethical? <strong>Absolute</strong>ly. Reviewers need reference-quality<br />

equipment with which to judge other reference-quality components—equipment<br />

they could never hope to afford. Moreover, equipment changes and is updated, and<br />

reviewers need to use the latest gear. Manufacturers see the value in lending equipment<br />

to reviewers after the review period has ended; not only is the product mentioned<br />

in subsequent issues, but the reviewer’s use of the product is an endorsement<br />

far more powerful than the review. Because reviewers can have virtually any products<br />

they want on a long-term basis, the ones they choose to live with are special<br />

indeed. Everyone wins: the manufacturer gets the exposure; the reviewer has the best<br />

tools available; and the reader is alerted to those products so good that the reviewer<br />

has chosen to live with them.<br />

There are two prerequisites that make this policy work. First, the magazine’s official<br />

stated policy must specify a time period from when the reviewer acquires the product<br />

to when the review appears in print and the product is ready for return to the manufacturer.<br />

At TAS, that period is six months. Second, when the manufacturer makes the<br />

inevitable call for the component’s return, the product goes back immediately.<br />

Products receive favorable reviews in TAS (and The Perfect Vision) for one reason—they<br />

deliver exceptional performance, value, or both. Anyone who says otherwise<br />

simply doesn’t know what he’s talking about.<br />

Robert Harley<br />

founder; chairman, editorial advisory board<br />

Harry Pearson<br />

editor-in-chief Robert Harley<br />

editor Wayne Garcia<br />

associate editor Jonathan Valin<br />

managing & music editor Bob Gendron<br />

acquisitions manager Neil Gader<br />

& associate editor<br />

copy editor Mark Lehman<br />

classical music Andrew Quint<br />

sub-editor<br />

equipment setup Michael Mercer<br />

editorial advisory board Sallie Reynolds<br />

advisor, cutting edge Atul Kanagat<br />

senior writers<br />

John W. Cooledge, Anthony H. Cordesman,<br />

Gary Giddins, Robert E. Greene, J. Gordon Holt,<br />

Fred Kaplan, Greg Kot, John Nork, Arthur S. Pfeffer,<br />

Paul Seydor, Kevin Whitehead, Roman Zajcew<br />

reviewers and contributing writers<br />

Soren Baker, Shane Buettner, Dan Davis, Frank Doris,<br />

Roy Gregory, Stephan Harrell, John Higgins, Sue Kraft,<br />

Mark Lehman, Arthur B. Lintgen, Anna Logg, David<br />

Morrell, Aric Press, Derk Richardson, Dan Schwartz,<br />

Gene Seymour, Aaron M. Shatzman, Alan Taffel<br />

design/production Design Farm, Inc.<br />

publisher/editor, AVGuide<br />

Chris Martens<br />

web producer Jerry Sommers<br />

<strong>Absolute</strong> Multimedia, Inc.<br />

chairman and ceo Thomas B. Martin, Jr.<br />

vice president/publisher Mark Fisher<br />

advertising reps Cheryl Smith<br />

(512) 439-6951<br />

Marvin Lewis, MTM Sales (718) 225-8803<br />

subscriptions, renewals, changes of address<br />

Phone (888) 732-1625 (U.S.) or (760) 745-2809<br />

(outside U.S.), e-mail<br />

absolutemultimedia@hutchins.com or write The<br />

<strong>Absolute</strong> <strong>Sound</strong>, Subscription Services, PO Box<br />

469024, Escondido, California 92046. Six issues: in<br />

the U.S., $42; Canada $45 (GST included); outside<br />

North America, $75 (includes air mail). Payments<br />

must be by credit card (Visa, MasterCard, American<br />

Express) or U.S. funds drawn on a U.S. bank, with<br />

checks payable to <strong>Absolute</strong> Multimedia, Inc.<br />

editorial matters<br />

Address letters to: The Editor, The <strong>Absolute</strong> <strong>Sound</strong>,<br />

PO Box 1768, Tijeras, New Mexico 87059, or e-mail<br />

rharley@absolutemultimedia.com.<br />

classified advertising<br />

Please use form in back of issue.<br />

newsstand distribution and local dealers<br />

Contact: IPD, 27500 Riverview Center Blvd., Ste.<br />

400, Bonita Springs, Florida 34134, (239) 949-4450<br />

publishing matters<br />

Contact Mark Fisher at the address below or e-mail<br />

mfisher@absolutemultimedia.com.<br />

Publications Mail Agreement 40600599<br />

Return Undeliverbale Canadian Addresses to<br />

Station A / PO Box 54 / Windsor, ON N9A 6J5<br />

Email: info@theabsolutesound.com<br />

<strong>Absolute</strong> Multimedia, Inc.<br />

8121 Bee Caves Road, Suite 100<br />

Austin, Texas 78746<br />

phone (512) 439-6951 · fax (512) 439-6962<br />

e-mail tas@absolutemultimedia.com<br />

www.theabsolutesound.com<br />

copyright© <strong>Absolute</strong> Multimedia, Inc., Issue 148, June/July 2004.The <strong>Absolute</strong> <strong>Sound</strong><br />

(ISSN #0097-1138) is published bi-monthly, $42 per year for U.S. residents, <strong>Absolute</strong><br />

Multimedia, Inc. 8121 Bee Caves Road, Suite 100, Austin, TX 78746. Periodical Postage<br />

paid at Austin, TX, and additional mailing offices. Canadian publication mail account<br />

#1551566. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to The <strong>Absolute</strong> <strong>Sound</strong>, Subscription<br />

Services, Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834. Printed in the USA.<br />

4 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

L E T T E R S<br />

No April Fool<br />

Editor:<br />

Presuming the comments on the<br />

Home Depot extension cord as loudspeaker<br />

cable were for real (this being<br />

the April issue), I think I just saved several<br />

hundred dollars. Think I’ll buy<br />

some more SACDs. Jon Thomas<br />

Home Depot Cables, Good!<br />

Editor:<br />

Would you be so kind as to convey<br />

my sincere thanks to Paul Seydor. (He of<br />

so little faith in cable importance<br />

[Loudspeaker Cable Survey, Part Two,<br />

Issue 147].) I have just spent several<br />

hours listening to the very best sound I<br />

have ever heard from my system.<br />

Yesterday—almost on a lark—I<br />

replaced $600+ worth of AQ Hyperlitz<br />

Silver speaker cable with $30 worth of<br />

Home Depot extension cord. The difference,<br />

in a word, stunning!!<br />

In fairness—two other minor<br />

changes were made—the HD cable is a<br />

full 8-foot true bi-wire with bare wire at<br />

the speaker terminals. The AQ was 5<br />

feet (Pierre Sprey [of Mapleshade] says<br />

that less than 8 feet always sounds<br />

worse) of internally biwired cable with<br />

spades at both ends. (I have also heard it<br />

said that internal bi-wiring mitigates<br />

much of bi-wiring’s advantages.)<br />

Whatever the reason—simple syner-<br />

gy perhaps, I am truly amazed at the<br />

sound of these cables and they aren’t<br />

even broken in yet. If the secret gets out<br />

(I guess it already has), there’ll be a lot of<br />

upset cable manufacturers.<br />

As they say: “It’s all about the music,”<br />

and what I am hearing is a substantial<br />

improvement in every parameter I can<br />

think of.<br />

If it matters: Speakers are Vandersteen<br />

2Ce Signatures and the amp is a Classé<br />

CA-100. David R. Kidd<br />

(Reader from the beginning)<br />

Home Depot Details<br />

Editor:<br />

I read with interest Paul Seydor’s<br />

comments on Home Depot speaker<br />

cable in the most recent issue of TAS. I<br />

was hoping to clarify the identification<br />

of this cable. The information might be<br />

of interest to other readers as well.<br />

In visiting Home Depot I found that<br />

there was no outdoor extension cord<br />

that carried its brand name and was told<br />

that no such brand existed in any store.<br />

Instead the “house” brand seemed to be<br />

from a company called Commercial<br />

Electric. The cable specified:<br />

“Medium Duty”<br />

14 AWG<br />

Suitable for 1875 maximum watts<br />

Insulated for 300V<br />

15Amp<br />

125V<br />

Designated as “indoor/outdoor”<br />

Made in the Philippines<br />

Is this the right cable? Also, can you<br />

identify specifically (with specs) the<br />

Black and Decker equivalent mentioned<br />

in the cable survey? (Are they the same?)<br />

On another point, how did you prepare<br />

the cable? This is a three-conductor<br />

configuration...Did you just cut off one<br />

of the three?<br />

Further detail on this would be a<br />

service to all readers, and personally I<br />

would greatly appreciate your clarification<br />

on these points as I’ve already been<br />

experimenting.<br />

Thank you for a great magazine and<br />

your enthusiasm in perpetuating music<br />

and audio. Chris Vollor<br />

PS. I tried the stuff at Home Depot and<br />

find it a bit “loose,” “hazy” in the<br />

mids/upper mids (possibly accounting<br />

for the open spaciousness), a little<br />

“sandy” but with some nice attributes in<br />

size and depth and overall engagement.<br />

<strong>Sound</strong>s “loud” to me compared with the<br />

AQ GR8 I’ve been using.<br />

Paul Seydor replies: I’m amazed and<br />

delighted by both the number and enthusiasm<br />

of readers’ responses to the inclusion in Neil<br />

Gader and my cable survey of Home Depot’s<br />

“speaker cable”—in reality, its heavy-duty<br />

outdoor extension cords. I wish I could take<br />

In the Next Issue<br />

Affordable speaker survey • Entry-level Edge electronics • Rotel’s 1068 integrated amplifier<br />

Simaudio’s Moon Equinox CD player • Musical Fidelity M1 turntable<br />

TAS Roundtable: The sound of old media (analog master tape, LP) and new media (SACD and DVD-Audio) debated<br />

…And an exclusive look at two speakers from fledgling speaker manufacturer Epiphany Audio<br />

6 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

L E T T E R S<br />

credit for discovering them; but I was first<br />

alerted to them by Robert E. Greene, who in<br />

turn heard about them from the designer of<br />

the one of the most literally accurate reference<br />

monitors ever made; and recently Tony<br />

Faulkner used the Black and Decker equivalent<br />

to drive his Quads at the Heathrow<br />

audio show in England.<br />

As I noted in the survey, the model designation,<br />

HD-14G—i.e., “H(ome) D(epot)<br />

14-G(auge)—is my own invention, so if you<br />

inquire about it that way at your local outlet,<br />

the sales people will be baffled. Instead, go<br />

directly to the electrical department where the<br />

outdoor extension cords are sold. You will find<br />

several alternatives. I selected the 14-gauge cord<br />

that is bright orange with a black stripe running<br />

along its length. This is a three-conductor<br />

cable terminated in a male AC-plug at one end<br />

and a female AC-plug at the other, and is<br />

available in several lengths (a 50-foot pair<br />

will run you about $30, not counting termina-<br />

tions; I used Pomona bananas, an excellent connector<br />

available for a couple of dollars at any<br />

decent electronic-supply house, but spade lugs<br />

are also fine, as are stripped ends). Many readers<br />

were apparently confused as to what I did<br />

with the third conductor. Well, you have three<br />

options: wire the hot lead with two conductors<br />

and the ground with the remaining one, wire<br />

the ground lead with two conductors and the<br />

hot with the remaining one, or simply leave the<br />

third conductor unconnected. I chose the last.<br />

There is, by the way, nothing magical<br />

about either Home Depot’s cords or the orange<br />

jacket. The color is dictated by the use for<br />

which the cords are made: to provide electricity<br />

to garden tools like powered hedge clippers,<br />

the brilliant orange easily seen against the<br />

greens of shrubs and lawns, the better to prevent<br />

accidentally cutting through a live AC<br />

cord that might otherwise blend in with the<br />

background. If you want a different color, at<br />

the same electrical supply-house that has<br />

Pomona bananas you’ll find essentially the<br />

same cords in bulk with black or beige jackets.<br />

Apparently some clever readers have<br />

already begun tweaking even this unprepossessing<br />

product, e.g., buying enough cord to<br />

use two lengths per channel, one for the hot,<br />

the other for the ground, all three conductors<br />

in each length connected. And some other<br />

readers have twisted the cords together into<br />

braids. Obviously, sky’s the limit here,<br />

including buying thicker cords (there’s a<br />

12-gauge and maybe a 10 as well). (I seem<br />

to recall Enid Lumley once saying she tried<br />

welding cables.) It’s certainly refreshing to<br />

find readers seeking sensible alternatives to<br />

extravagantly expensive “audiophile” cables.<br />

Finally, in answer to those who’ve<br />

inquired if I’ve tried any of these tweaks or<br />

experimented with other kinds of unconventional<br />

speaker cable, the answer is a firm no.<br />

After conducting surveys of interconnects and<br />

speaker cables—and I believe I can speak for<br />

8 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

Neil Gader here also—I’ve listened to enough<br />

wire to last a lifetime! Too much music and<br />

too little time to waste on a problem that<br />

remains, for me, about as far as you can get<br />

from a top priority in the first place and one<br />

that has been effectively solved in the last.<br />

Roundtable Feedback<br />

A Middle Ground?<br />

Editor:<br />

I enjoyed reading the Tubes vs.<br />

Transistors Roundtable discussion in<br />

Issue 147, but I’m left wondering why<br />

the distinguished panel didn’t mention<br />

or discuss the option of combining (suitably<br />

matched) solid-state and tube gear<br />

in a complementary and synergistic<br />

manner, in order to possibly enjoy the<br />

best of both worlds. For example, one<br />

might choose to combine a very accurate<br />

and “fast” solid-state preamplifi-<br />

er (such as the Spectral DMC-15) with<br />

the warmth and lushness of a wellmatched<br />

tube amplifier. If you and the<br />

other distinguished panel members plan<br />

to hold further discussions on the tubes<br />

vs. transistors debate, I hope that<br />

you will address the advantages and disadvantages<br />

of this “hybrid” approach.<br />

Kurt Heintzelman<br />

Roundtable Laughter<br />

He Who Laughs Last…<br />

Editor:<br />

Genuine laughter! Have not<br />

laughed so much for ages! Electron flow<br />

indeed! There is undoubtedly a significant<br />

difference between tube and transistor<br />

amplifiers by and large. Those of<br />

us brought up in the thirties and forties<br />

will recognize the even harmonic distortion<br />

which valves tend to produce. That<br />

L E T T E R S<br />

plus the transistor amplifiers’ undoubted<br />

ability to produce nasties such as<br />

intermodulation distortion and there<br />

you are. (Even, as distinct from odd, harmonics<br />

can sound rather pleasant.) As<br />

someone who has done his bit for amplifier<br />

design (current dumping etc.) I can<br />

assure you that mystery does not come<br />

into it, but non-linearity certainly does.<br />

A. Sandman (Dr.)<br />

M.Phil., PhD., M.I.E.E.<br />

See the following letter.—RH<br />

Laughs Best<br />

Editor:<br />

Interesting piece, this Tubes vs.<br />

Solid-State. I would like to comment<br />

briefly on an interesting issue raised by<br />

Paul Seydor, being the so-called “digital”<br />

nature of our hearing:<br />

We can absolutely not compare our<br />

WWW.THEABSOLUTESOUND.COM 9

L E T T E R S<br />

hearing with any “digital” system for<br />

one all-overruling reason, which is the<br />

fact that “any” digital system is locked<br />

by a steady clock frequency, resulting<br />

effectively in a steady “refresh” of the<br />

presented information, independent of<br />

frequency; whereas the hearing uses NO<br />

clock and every “nerve” action is totally<br />

individual, therefore we have many,<br />

many random moments of reception,<br />

and at one given moment in time our<br />

hearing system is receiving and processing<br />

multiple stimuli. This makes our<br />

hearing essentially “continuous.”<br />

Secondly, briefly regarding even/<br />

odd/lower/higher order harmonics:<br />

Omitted in this first discussion is the fact<br />

that most distortions of solid-state gear<br />

are lower than those of tube gear by a factor<br />

of 100 or more. This difference must<br />

be incorporated in the reasoning of the<br />

influence of distortions on our perception<br />

of musical information. Otherwise it will<br />

be a hollow argument.<br />

I myself would argue that two other<br />

phenomena play the dominant role in the<br />

differences between tubes and solid-state:<br />

One is the fact that electrons (and<br />

holes) travel 10 times faster in a vacuum<br />

than in doped silicon, and it takes<br />

another order of magnitude of time for<br />

the electrons to get moving in the first<br />

place (avalanche effect; at least in bipolar<br />

transistors, FETs are faster), which<br />

adds up to a difference in propagation<br />

delay of 100. Tube amps therefore have<br />

100 times (not really because of the<br />

transformers but for the sake of the<br />

argument) higher transition speed and<br />

hence a 100 times lower negative influence<br />

of the always-too-late negative<br />

feedback. In my view this is the single<br />

most dominant factor of detail-masking<br />

in solid-state amplifiers. Feedback that<br />

is too late is in fact truncating low-level<br />

information instead of reducing<br />

“dynamic” distortion products. In tube<br />

amps this feedback is thus 100 times<br />

more effective, dynamically. So in fact<br />

to reach “solid-state levels” of negative<br />

“NFB artifacts,” you can apply 100<br />

times more feedback in a tube amplifier.<br />

When you do that I bet that they<br />

don’t sound very different from each<br />

other anymore.<br />

Secondly I would say that the output<br />

impedance in conjunction with NFB<br />

also plays a major role here: tube amps<br />

with damping factors of 8...80 do not do<br />

a good job in eliminating ringing of the<br />

moving mass (cone, motor, air) in loudspeaker<br />

systems.<br />

This is bad and good. Dynamic<br />

loudspeakers have their most problematic<br />

nonlinearities just around the center<br />

position of the movement, i.e., in its<br />

physical crossover region.<br />

When a low/mid unit is still moving<br />

somewhat after a bass burst, then lowlevel<br />

information is more present because<br />

it “rides” on the “ringing” of the loudspeaker.<br />

So it is more audible, although<br />

maybe a little bit distorted because of<br />

mild IM—or Doppler effects, as it is not<br />

“swallowed” by the problematic lowlevel<br />

linearity of a cone unit. (This is why<br />

E’stats and M’stats are far more revealing.)<br />

However low-level detail also suffers<br />

from the same mechanism because of<br />

masking, when the cone is still recovering<br />

from the bass pulse. But since the<br />

concerned frequencies differ from each<br />

other this will be a mild effect.<br />

Hope this adds a little bit to the discussion,<br />

which I find in fact an essential<br />

one. You are literally raising fundamental<br />

questions. This can only be done<br />

properly in TAS.<br />

Marcel Croese, Creato Audio<br />

Hidden Factor in Tubed <strong>Sound</strong>?<br />

Editor:<br />

Your TAS Roundtable on “Tubes vs.<br />

Solid-State” [Issue 147] was fascinating<br />

and insightful. Several of the roundtable<br />

members commented on the significant<br />

differences in midrange reproduction<br />

between solid-state and tubes. While the<br />

members explored many facets of this<br />

timeless question, one was overlooked. I<br />

believe the quality of low- and high-frequency<br />

reproduction has a profound effect<br />

on our perception of midrange accuracy. I<br />

submit that the midrange will sound different<br />

in systems with identical midrange<br />

10 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

L E T T E R S<br />

reproduction but differing low- and<br />

high-frequency reproduction capabilities.<br />

Broadly and generally speaking, the<br />

best solid-state electronics are perhaps<br />

more linear in their reproduction of the<br />

full frequency spectrum than are the finest<br />

tube electronics. I believe this affects the<br />

way we perceive the midrange reproduction<br />

of the two. Solid-state electronics that<br />

assault the state of the art offer massive<br />

midrange detail (including superb lowlevel<br />

detail), liquidity, and “continuousness,”<br />

along with deep, solid bass and natural<br />

highs. I have spent countless evenings<br />

in concert halls enjoying unamplified<br />

symphonic music, and to me the best<br />

solid-state electronics offer a more realistic<br />

picture of the live event—top to bottom—than<br />

tubes. Don’t misunderstand; I<br />

too can be seduced by the lovely bloom<br />

and “roundedness” of tubes. But to my<br />

ears, the best solid-state sounds more like<br />

the real thing.<br />

Speaking of the real thing, I am<br />

amused at some equipment reviews comparing<br />

the way a pop singer sounds with<br />

different equipment. Unless the reviewer<br />

has heard the real thing—unamplified—<br />

how can the reviewer make claims that<br />

one sounds better than the other? There<br />

is after all an absolute reference—the real<br />

thing. Unfortunately, in the pop world<br />

the “real thing” consists of live performers<br />

reproduced through bad microphones,<br />

amplifiers, and speakers. Hardly<br />

an absolute reference. And too often, we<br />

ignore the impact of the microphone and<br />

other recording equipment in capturing<br />

the real thing. Do tubes ameliorate nasties<br />

in the recording chain that solidstate<br />

mercilessly unmasks? Who knows?<br />

Anyway, your roundtable discussion was<br />

illuminating and provocative. I look forward<br />

to more such discussions from your<br />

staff of golden ears. Ken McCarty<br />

Mark Levinson Speaks Up<br />

Editor:<br />

I want to thank you for the recent<br />

numerous and kind mentions of my<br />

work during the last 30 years, both for<br />

equipment and recording, that appeared<br />

in your magazine. I’m gratified that HP<br />

chose the JC-2 for inclusion in his Top<br />

Ten [Issue 145]. In particular, I enjoyed<br />

Jon Valin’s words of praise of the Red<br />

Rose Music series of SACDs.<br />

There are a few factual errors in HP’s<br />

Top Ten story that need correction.<br />

On page 168, HP states that “Mark<br />

Levinson, the man, bankrupted the company<br />

that later became Madrigal.” This<br />

is simply not true, and the facts are<br />

available to anyone who gets the documents,<br />

which are on the public record in<br />

Federal Court files.<br />

The purchasers of Mark Levinson<br />

Audio Systems (MLAS) forced me out of<br />

the company and ran it for five years<br />

with full financial control. They had<br />

originally valued the company at $1.8<br />

million. They then stopped paying the<br />

bank debt, for which I was personally<br />

liable, forcing the bank to come after me<br />

for the money. They also stopped paying<br />

the vendors, who eventually forced<br />

MLAS to file for bankruptcy in the<br />

hopes of getting paid something. The<br />

original purchasers eventually bought<br />

the assets of MLAS for around $110k<br />

and moved those assets to a new company<br />

called Madrigal. I had been kept out<br />

of the picture during the five years<br />

before the bankruptcy and knew nothing<br />

about these activities. There are documents<br />

on file in Federal Court records<br />

which prove that the purchasers planned<br />

this bankruptcy a year in advance to<br />

eliminate my 43% of the stock. The<br />

purchasers subsequently sold Madrigal<br />

to Harman. I have had no involvement<br />

with Madrigal or Harman.<br />

The point is that the purchasers, far<br />

from being saviors, acquired a company<br />

of worth, planned a bankruptcy a year in<br />

advance, and forced it through bankruptcy<br />

to eliminate my stock.<br />

HP says that Cello was “essentially<br />

an upscale high-end boutique for the<br />

12 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

L E T T E R S<br />

rich and famous.” In fact, Cello’s customers<br />

included many people who were<br />

neither rich nor famous, a good number<br />

of whom had purchased what HP recommended<br />

and were not satisfied. Many of<br />

these people still have their Cello systems,<br />

enjoying them almost twenty<br />

years later, with no service required.<br />

The bankruptcy of Cello is a truly sad<br />

tale. In an apparent gesture of support,<br />

one of our customers acquired a controlling<br />

interest in 1997 and, in a totally<br />

shocking move, decided to stop manufacturing<br />

products. He closed the factory,<br />

putting 20-year veterans in the street,<br />

and reoriented Cello as a custom-installation<br />

company selling conventional products<br />

through ultra-costly installers. The<br />

only reason the Cello factory closed was<br />

that a very wealthy man chose to discard<br />

it. I should have made a better deal that<br />

allowed me to protect the company.<br />

It is true that I allowed men with<br />

hidden agendas to come into MLAS and<br />

Cello without adequate protection for<br />

the companies and myself. It is important<br />

to recognize that it was my former<br />

partners who forced MLAS through<br />

bankruptcy, took my name for nothing,<br />

and have tried all these years to blame<br />

the troubles on me. These are facts, not<br />

opinions. Mark Levinson<br />

Taking Issue with Garcia on<br />

Stones<br />

Editor:<br />

I am a longtime reader and subscriber<br />

to The <strong>Absolute</strong> <strong>Sound</strong>. I have also<br />

been a mastering engineer for over 22<br />

years (www.Dongrossinger.com). I respectfully<br />

disagree with Wayne Garcia’s review<br />

of the recent releases of the early Rolling<br />

Stones on vinyl [Issue 146].<br />

I am the mastering/cutting engineer<br />

who cut most of the releases in question.<br />

The cutting of this project was clearly a<br />

labor of love for ABKCO, which actually<br />

went to three other mastering studios to<br />

attempt the project’s completion (without<br />

success) before coming to me, on Bob<br />

Ludwig’s recommendation, to finally get<br />

the job done to everyone’s satisfaction<br />

(please excuse the pun). ABKCO went the<br />

extra mile: Jody Klein went past release<br />

date after release date and I would guess<br />

over budget as well to get the best results.<br />

There were extensive comparative<br />

listening sessions done at Europadisk<br />

Mastering, at ABKCO, and at other<br />

facilities in New York City to determine<br />

the new album’s “trueness to the original”<br />

under the most stringent conditions.<br />

I worked closely with Teri Landi,<br />

ABKCO’s chief archivist, who located all<br />

of the original masters used in the SACD<br />

and vinyl project. I believe she is,<br />

because of her painstaking research, the<br />

most qualified person for an authoritative<br />

comparison between sources.<br />

Additionally, a complete set of vinyl test<br />

pressings was sent for evaluation to Bob<br />

Ludwig at his mastering facility in<br />

Maine and were approved by him as<br />

well. As a fanatical Stones fan myself, I<br />

would not have let the project come to<br />

completion without feeling that the<br />

work was done right.<br />

It is indeed curious that the album<br />

mentioned by Mr. Garcia as having “a<br />

grainy edge” which he attributes to the<br />

D.M.M. process, Let It Bleed, was not cut<br />

on the D.M.M. lathe, but rather to lacquer<br />

at another studio. This would have<br />

been easily determined if he chose to do<br />

his research because each of the albums I<br />

cut using the Direct Metal Mastering<br />

process was clearly marked as such in the<br />

lead-out groove of the album. I<br />

cynically suspect (with no proof) that<br />

Mr. Garcia read the press release that<br />

stated “D.M.M. cutting” and automatically<br />

damned the entire set of albums<br />

with a preconceived idea of their sound.<br />

It has also been my experience in over 22<br />

years of cutting for vinyl on all sorts of<br />

lathe setups, that D.M.M. is uniquely<br />

suited for a transfer of this vibrant, yet<br />

archival, material to the vinyl medium<br />

because of its accuracy.<br />

The albums were indeed cut from<br />

the SACD masters using a custom, stateof-the-art<br />

Ed Meitner DSD digital-toanalog<br />

converter and a purist, analog<br />

Neumann cutting chain to retain all of<br />

the qualities of the recent remastering.<br />

The entire setup was assembled exclusively<br />

for this project. The remastering<br />

process as done by Bob Ludwig was<br />

extremely involved and the noise reduc-<br />

14 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

tion, editing, and equalization used precluded<br />

the use of the raw original reelto-reel<br />

masters. The final results of the<br />

SACD mastering far exceeded any mastering<br />

job that anyone could have done<br />

using a single pass of almost 40-year-old<br />

tape. There was no shortcut involved in<br />

the choice to use the SACD masters, just<br />

a desire to get the best quality master for<br />

the transfer.<br />

It may be too late at this point for a<br />

reevaluation by someone on your staff<br />

who will give a full, unbiased, and<br />

exhaustive listening to my work (and<br />

the hard work of all the folks involved in<br />

the project), but I believe the results<br />

speak for themselves. I heartily recommend<br />

the Stones vinyl releases to all fans<br />

and vinyl aficionados alike, with pride.<br />

Don Grossinger<br />

Chief Mastering Engineer<br />

Europadisk, LLC<br />

Wayne Garcia comments: Not being a<br />

cynic myself, I have no reason to doubt Mr.<br />

Grossinger’s detailed account of the care that<br />

went into these LP releases. As to whether the<br />

relatively hollow, edgy, rhythmically static<br />

sound I heard from these records was the<br />

result of D.M.M. mastering or not (and contrary<br />

to Mr. Grossinger’s self-admittedly<br />

cynical suspicion, I did not approach these<br />

sides with “a preconceived idea of their<br />

sound”), from the DSD masters or not, or for<br />

any other reason is not strictly the point. I<br />

was speculating as to why they might sound<br />

the way they do, not making concrete pronouncements.<br />

I reported what I heard and<br />

stand by my opinion.<br />

HP’s Vinyl Super Disc List<br />

Editor:<br />

I have been a loyal reader and supporter<br />

of The <strong>Absolute</strong> <strong>Sound</strong> since the mid-<br />

’70s—when I was poor, but proud—and<br />

later as a subscriber for many years, still<br />

proud, but not quite as poor (almost).<br />

I started to collect vinyl in the mid-<br />

’60s, buying retail. Really got hooked<br />

on finding the gems based on HP’s<br />

Super Disc List in the ’80s—used record<br />

stores, thrift stores, garage sales. I also<br />

devised a home-made record-cleaning<br />

machine based on the concepts of sever-<br />

al of the machines on the market.<br />

I have been lucky to find a large<br />

number of the items on the Super Disc<br />

List. There have been a few titles I disagreed<br />

with (perhaps the wrong pressings),<br />

but, all in all, the list has been a<br />

great resource.<br />

Please forgive the background. My<br />

question: It has been several years since<br />

L E T T E R S<br />

The <strong>Absolute</strong> <strong>Sound</strong> has published a<br />

vinyl Super Disc List. Is one in the<br />

works? If not, please consider this as a<br />

humble request to develop and publish<br />

an update to the vinyl list. Clay Ancell<br />

An excellent suggestion, Mr. Ancell. HP<br />

is working on a new list for an upcoming<br />

issue. —RH<br />

WWW.THEABSOLUTESOUND.COM 15

I N D U S T R Y N E W S<br />

The Present and<br />

Future of Hi-Rez Audio<br />

More than four years after the launch of SACD and<br />

DVD-A, it’s still impossible to predict the future of<br />

either format. But over the course of the last few<br />

months, several new developments shed light on<br />

the prospects for each.<br />

As I reported in Issue 146, Sony Music spent upwards of<br />

$30 million to promote SACD via a campaign involving<br />

Rolling Stone, Clear Channel radio, and Circuit City. Launched<br />

in late November 2003, the blitz came on the heels of<br />

Columbia/Legacy’s Bob Dylan Revisited hybrid SACD series.<br />

Yet one wonders if it had the intended impact.<br />

Lately, SACD happenings from Sony haven’t been. Aside<br />

from a handful of titles, including two James Taylor reissues<br />

(review, TAS 147), the SACD scene at Sony has been quiet. To<br />

entice other labels, Sony paid willing participants to release<br />

titles on SACD and footed the advertising bills. It’s also<br />

rumored that Sony paid EMI/Capitol $1 million to release<br />

Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon on SACD. (Capitol hasn’t<br />

produced an SACD since then.)<br />

At this juncture, Harmonia Mundi and Telarc remain<br />

SACD’s most active players. If their monthly releases were<br />

taken out of the equation, new SACDs would be few and far<br />

between. And since those labels specialize in classical, they<br />

aren’t turning out titles that sell in massive quantities,<br />

although their aggressiveness has possibly made SACD the<br />

classical format of choice for the future. Jazz and pop are a different<br />

story.<br />

Recent hybrid stereo SACDs from Songlines and Fantasy<br />

(reviews, TAS 146 and 147) were the first new jazz releases in<br />

some time; indeed, save for a scattering of Telarc discs, multichannel<br />

jazz remains a largely untapped field. Most revealingly,<br />

Bob Dylan’s Bootleg Series Volume 6 (review, this issue) is not<br />

being released on hybrid SACD, reversing the promise that<br />

Sony made last August when it included a hybrid sampler in<br />

its soundtrack to Masked and Anonymous.<br />

News on the DVD-A front appears to be better. Recently,<br />

companies invested in the technology formed the DVD-A<br />

Council to organize and market its strengths. Only 700<br />

DVD-As are currently available, but several notable albums<br />

are slated for late spring and early summer release. Warner<br />

Brothers is supplying most of the product, including older<br />

selections from R.E.M. and Frank Sinatra. As reported in TAS<br />

147, Silverline secured the rights to the Omega Classics catalog.<br />

Upcoming DVD-As from BMG, J, and Arista offer<br />

hope that more contemporary pop and R&B will finally<br />

become available, and recent releases suggest that the muchballyhooed<br />

bonus features (video extras, onscreen lyrics) are<br />

slowly becoming a reality, albeit at the expense of production<br />

delays. But the accurate barometer of both formats may be<br />

what is happening at Universal. By releasing DVD-A titles it<br />

has already issued on SACD, the media giant is practicing a<br />

let-the-marketplace-decide strategy. While no victor has<br />

been declared, Universal just switched its SACD advertising<br />

over to DVD-A.<br />

In spite of this, both new formats are light-years away<br />

from emerging from their niche positions. Most mainstream<br />

reviews of the Bob Dylan, Rolling Stones, and The Who<br />

SACDs didn’t mention a word about high-rez formats or surround<br />

sound. Radio could care less. Overall sales—save for the<br />

Stones, Dylan, and Floyd SACD hybrids—are infinitesimal<br />

when compared to conventional CDs. Add to this the recent<br />

cutbacks at Warner Brothers—which resulted in the laying off<br />

of the publicist in charge of DVD-A titles—and the company’s<br />

interest in DVD-A could entirely disappear with one fell<br />

swipe of new owner Edgar Brofman, Jr.’s red pen.<br />

Making titles available on SACD or DVD-A months after<br />

their CD/LP release (and after thousands of copies have already<br />

been sold) is yet another disincentive to most music buyers.<br />

Even on the rare occasions where both formats hit stores on the<br />

same day, as was the case with DVD-As of Fleetwood Mac’s Say<br />

You Will and R.E.M.’s In Time, advertisements didn’t mention<br />

the DVD-As or even reprint the DVD-A logo. Hybrid SACDs<br />

that eliminate the need for separate discs seem to be an obvious<br />

solution, but it has gone unrealized by Sony. Even with<br />

Sony’s new Indiana production line, only one Sony title—<br />

James Carter’s Gardenias for Lady Day—has been released in<br />

this fashion. Questions surrounding mass-production capabilities,<br />

necessary for any major new release, remain a concern.<br />

So does the inability to copy new-format discs to portable<br />

devices like Apple’s iPod. In this age of Internet piracy, labels<br />

view as advantageous most kinds of download-proof software.<br />

But to most listeners under the age of 35 who listen to music<br />

on the go, it’s an unacceptable deterrent. To this extent, more<br />

contemporary titles are needed and more labels need to be persuaded<br />

to get involved. Aimed at indie-rock audiences that<br />

place a premium on sound quality, Matador’s day-in-date<br />

hybrid SACD issue of Mission of Burma’s high-profile OnOffOn<br />

(review, this issue) is a start, as was Barsuk’s release of DCfC’s<br />

critically acclaimed Transatlanticism (review, TAS 146).<br />

There’s also another “new” format already here, called One<br />

Disc. Debuting on Kathleen Edwards’ Live From the Bowery<br />

Ballroom EP, released in December by Rounder Records, the<br />

technology affords programming on both sides of a single disc,<br />

offering audio on one and DVD-Video on another. Credible<br />

sources hint that DVD-Audio is considering a switch-over to<br />

this technology, though problems with the disc’s thickness (it<br />

won’t play in car CD players) and the likelihood one side is<br />

going to become scratched need to be addressed. However, one<br />

thing is clear: Consumers have positively responded to incentive-based<br />

releases packaged with bonus CDs and DVDs, like<br />

Neil Young’s Greendale and Metallica’s St. Anger. Following the<br />

formula that’s made DVD-Video into a phenomenon, more<br />

record labels are expected to follow suit.<br />

16 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

As we have since their inception,<br />

we’ll continue to review new-format software<br />

releases in the Music section, and<br />

provide you with our list of the best titles.<br />

Because both have tremendous potential,<br />

it would be a shame to see either format<br />

coast on life support or be relegated to<br />

novelty items. But if significant progress<br />

is to occur, conditions need to improve,<br />

and soon. BOB GENDRON<br />

Nuts About Hi-Fi<br />

Hosts Harley<br />

Book Signing,<br />

Manufacturer<br />

Seminars<br />

Nuts About Hi-Fi in Silverdale,<br />

Washington, will host a book<br />

signing and series of manufacturer<br />

seminars on Saturday, June<br />

5. Robert Harley of The <strong>Absolute</strong> <strong>Sound</strong><br />

and The Perfect Vision will be signing<br />

copies of the just-published Third<br />

Edition of The Complete Guide to High-End<br />

Audio as well as Home Theater for Everyone.<br />

Representatives from Krell, Dali,<br />

Wilson Audio, NAD, PSB, and<br />

Marantz will be on hand to demonstrate<br />

equipment and answer questions.<br />

Robert Harley will sign books at 3pm<br />

and 6pm, and will be available<br />

throughout the day to answer questions.<br />

The event begins at 2pm, and<br />

refreshments and snacks will be served.<br />

Music for the event will be provided by<br />

the new Wilson X-2 Alexandria loudspeakers<br />

driven by Krell Master<br />

Reference amplifiers.<br />

Nuts About Hi-Fi, 10100 Silverdale<br />

Way, Silverdale, WA 98383. Phone:<br />

(360) 698-1348, (800) 201-hifi (toll-free<br />

in WA only). www.nutsabouthifi.com.<br />

E-mail: bbenson@silverlink.com.<br />

Quad Book<br />

Written and compiled by Ken<br />

Kessler of Hi-Fi News,<br />

Quad—The Closest Approach<br />

[ISBN 0 954 57420 6] is<br />

both pleasurable reading and a valuable<br />

addition to the historical literature of<br />

audio. (The title refers to Quad’s advertising<br />

slogan, “The closest approach to<br />

the original sound.”) In addition to<br />

Kessler’s own thoughts, it contains<br />

interviews with Quad’s late founder,<br />

Peter Walker, his son Ross, and other<br />

people who were associated with Quad.<br />

The book also contains facsimile reproductions<br />

of Peter Walker’s fundamental<br />

papers on amplifier and speaker design,<br />

nostalgic reprints of old Quad advertisements,<br />

photos of ceremonies honoring<br />

Quad, and so on. This miscellany is<br />

nicely organized and unified by<br />

Kessler’s prose and presentation, and<br />

the whole book is a most attractive<br />

visual package as well as being fascinating<br />

reading. No book contains<br />

everything, but I would have liked to<br />

see reprinted some of the detailed technical<br />

reviews of Quad speakers by<br />

Trevor Atwell (on the ESL 63),<br />

Richard Heyser’s slightly jaundiced<br />

but also interesting viewpoint, and<br />

perhaps Martin Colloms on the original<br />

Quad ESL, revisited just a few years<br />

ago. The book does contain some references,<br />

but again it would have been<br />

good to have something along the lines<br />

of a complete bibliography, although<br />

admittedly that would have been a<br />

considerable labor to prepare. Still, the<br />

book is so charming, interesting, and<br />

informative that to ask for more is no<br />

doubt a little greedy. For those of us<br />

who have either owned or dreamed of<br />

owning Quad equipment—as I<br />

dreamed of it long before I could afford<br />

it—reading this book is all but hypnotic.<br />

And while the $80 price would<br />

be a bit high were it an ordinary book,<br />

it is so elegantly printed and presented<br />

(with the dimensions of an LP record<br />

cover, but a lot thicker than an LP)<br />

that it is in the “coffee table book” category.<br />

The history of audio is all too<br />

often preserved only in magazine articles,<br />

inaccessible to all but the most<br />

determined library sleuths. It is a<br />

pleasure to see Peter Walker’s great<br />

contributions to audio and his company’s<br />

remarkable products memorialized<br />

in book form, and one hopes the<br />

prospect of the book brightened his<br />

last days. ROBERT E. GREENE<br />

18 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

on the Horizon<br />

futureTASProducts NEIL GADER<br />

Mo’ Fi From MoFi<br />

originally designed for use in Mobile<br />

Fidelity <strong>Sound</strong> Lab’s mastering facilities,<br />

the OML-1 compact monitor and<br />

the OML-2 tower will be equally<br />

at home in your living room.<br />

Utilizing proprietary custommade<br />

drivers, crossovers, cabinets,<br />

and hardware, the OML series is<br />

said to exhibit superior dispersion<br />

characteristics and overall sonics<br />

at an affordable price. The compact<br />

12.5" high OML-1 uses a<br />

1.25" silk-dome tweeter and a<br />

6.5" mica-Kevlar-impregnated<br />

paper cone. The OML-2 adds a<br />

second mid/bass driver in a 2.5way<br />

configuration. Both speakers<br />

have a nominal impedance of 6<br />

ohms. Sensitivity for the bookshelf<br />

is 88dB, for the 38" tower, 84dB.<br />

Price: OML-1, $999; OML-2,<br />

$1999<br />

www.mobilefidelitysoundlabs.com<br />

New Balance for the Un-Shure<br />

the REK-O-KUT Stylus Force Gauge from Esoteric<br />

<strong>Sound</strong> should be a great alternative to the trusty Shure.<br />

Made of sturdy plastic it comes with a set of weights for<br />

0.25 to 5.75 gram measurement. Operation is simple and<br />

relies on the principle of a basic laboratory balance. Easy to<br />

upgrade to even greater force measurements.<br />

Price: $24<br />

www.esotericsound.com<br />

Two Loaded Revolvers<br />

revolver Loudspeakers of England has set its sights on affordable<br />

performance with stereo and multichannel speaker offerings.<br />

Designed by Michael Jewitt, formerly chief designer for<br />

Mordaunt-Short, Epos, and Heybrook, the compact R33 is fitted<br />

with a 1" aluminum-dome tweeter and a 6.5" woven-fiberglass<br />

mid/bass. The 36.5" floorstanding R45 adds another pair of 6.5"<br />

woofers to extend low frequencies down to 38Hz. Both speakers<br />

are rated 90dB-sensitive, with impedances of 8 ohms, and can be<br />

driven with as little as 6 watts (SET lovers take note!), or up to<br />

100–200 watts of solid-state. The Revolvers are magnetically<br />

shielded for use in both two-channel and home-theater applications.<br />

Available in pearlized maple and fabric with wood veneers.<br />

Price: R33, $995/pr; R45, $1795/pair; R25 center channel, $695<br />

www.ossaudio.com<br />

20 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

Bottom Feeder<br />

focal-JMlab’s Sub Utopia Be means serious subwoofing.<br />

The Be sports a 16" sandwich cone driver<br />

with a 3" Kapton voice coil (the magnet array alone<br />

weighs in at 17.6 lbs.). The massive enclosure has<br />

panel thicknesses of up to 2.5". Add a 1000W<br />

switching amplifier and the sub’s fighting weight is a<br />

pumped-up 121 pounds. The Sub Utopia Be is capable<br />

of delivering a true 20Hz at nearly 120dB of<br />

sound pressure in test conditions. In average realworld<br />

listening rooms, it goes even deeper, down to<br />

16Hz at 128dBSPL. The port’s unique profile is said to reduce distortion<br />

and noise artifacts by a factor of 10. Connectivity matches the exemplary fit and finish,<br />

with RCA, XLR stereo, and LFE inputs.<br />

Price: $6000<br />

www.audioplusservices.com<br />

What’s in a Nait?<br />

england’s Naim Audio has been building<br />

various editions of its Naim integrated amplifier<br />

for over 20 years. The Nait 5 ($1550) was<br />

highly recommended in these pages by both Editor<br />

Wayne Garcia and Editor-in-Chief Robert Harley for its natural<br />

tonal balance, outstanding dynamics, engaging musicality, and terrific<br />

value. That said the Nait was slightly fussy, requiring the use of non-standard<br />

(in the US) DIN interconnects and Naim’s own speaker cables. With the new Nait 5i,<br />

Naim has taken all the good stuff about the Nait, upped the power from roughly 30 to<br />

50Wpc, lowered the price by a few hundred, and made the unit far more versatile with the addition<br />

of RCA jacks as well as versatility with any speaker cable. Expect a review in the near future.<br />

Price: $1350<br />

www.naimusa.com<br />

Defying Gravity And Drag<br />

the Ganymede V.C.S. (Vibration Control System) is not a typical set<br />

of aluminum footers. Rather, the unique system consists of a round steel<br />

bearing sandwiched between a top and bottom puck. When placed<br />

beneath a CD player or amplifier it allows lateral movement even as it<br />

mass loads the component. Ganymede claims the V.C.S. provides isolation<br />

from transient vibrations while reducing the pernicious drag that<br />

cables create. When the VCS is properly set up, gear appears to float on<br />

it when lightly touched. The latest version now features an elevation on<br />

the outside of the top and bottom pucks allowing for more intimate<br />

contact between component and shelf/surface.<br />

Price: $299 (set of three)<br />

WWW.THEABSOLUTESOUND.COM 21

S T A R T M E U P<br />

Meeting High-End Expectations on a Modest Budget<br />

Jerry Sommers<br />

Acrucial and exciting part of<br />

choosing gear is the search for<br />

synergy among components<br />

within your allotted budget. I<br />

recently had the chance to audition a<br />

system that included the Philips<br />

DVD963SA DVD/SACD player, a<br />

Portal Panache integrated amplifier, and<br />

Definitive Technology’s BP7004 loudspeakers.<br />

The system met all of my<br />

expectations and then some, giving me<br />

everything from deep satisfying bass to a<br />

tonally accurate rendering of midrange<br />

and treble instruments, complete with<br />

the spine-tingling sound of air and space<br />

around those instruments. In short, this<br />

system put the fun back in listening—<br />

and at a reasonable price. The system’s<br />

components had an uncanny complementary<br />

quality—each element playing<br />

off the strengths of the others.<br />

The Philips DVD963SA offers<br />

almost everything I would ever want in<br />

a digital player, including progressive-<br />

scan DVD playback, multichannel<br />

SACD playback, 96kHz and 192kHz<br />

CD upsampling, MP3 decoding, and<br />

CDR/RW playback. I first read about<br />

this post-modernistic-looking player in<br />

Wayne Garcia’s short review in the<br />

SACD, DVD-A, and Universal Players<br />

Special Feature in TAS 145. There,<br />

Wayne characterized the 963SA as<br />

“warm and sloppy,” but he tempered his<br />

comments with the observation that his<br />

interconnect cables cost more than the<br />

entire DVD963SA. My findings were<br />

considerably more positive, as I was<br />

using this player in a much more moderately<br />

priced system.<br />

The most notable, exciting, and useful<br />

feature in the DVD963SA is its<br />

upsampling circuitry. Audio CDs can be<br />

upsampled to either 96kHz or 192kHz,<br />

and I found the fun factor went up a<br />

notch as I heard subtle nuances that<br />

brought new life to my huge catalog of<br />

CDs. “The 3 rd Planet” from Modest<br />

Mouse’s The Moon and Antarctica [Sony],<br />

starts with a lightly plucked acoustic<br />

guitar that quickly shifts to full-on<br />

acoustic rage—a transition the Philips<br />

accomplished with ease, without sacrificing<br />

momentum or focus. As the<br />

rhythms became more complex, instruments<br />

didn’t bleed into one another;<br />

instead, I was able to discern each easily,<br />

without losing track of the rhythm of<br />

the piece. The acoustic guitars in the<br />

song’s introduction sounded full-bodied<br />

yet retained such subtle nuances as the<br />

pick scrapes and finger screeches you<br />

often hear when moving your hand from<br />

different neck positions on the guitar.<br />

These brilliantly reproduced details gave<br />

the illusion of musicians playing in a<br />

real space, and made the system so transparent<br />

it seemed to disappear.<br />

If you want to step up to a higher<br />

level of full-bodiedness and resolution,<br />

SACD on the 963SA certainly delivers.<br />

Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon<br />

[Capitol] in stereo SACD was<br />

more three dimensional and<br />

revealing than its CD layer. On<br />

“Breathe,” the bass drums and<br />

cymbals sounded more robust;<br />

electric guitar, bass guitar, and<br />

synths were more open. If<br />

you’ve been wanting to get<br />

into SACD, the DVD963SA<br />

will make your transition to<br />

the new format quite satisfying.<br />

Indeed, with CD upsampling,<br />

SACD playback, popular<br />

format playability, and a<br />

progressive-scan DVD player,<br />

the DVD963SA has even more<br />

of what I want in a player than<br />

some respected high-end players<br />

I’ve auditioned in the past.<br />

The Portal Panache is a<br />

22 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

thirty-two-pound heavyweight integrated<br />

amplifier from Portal Audio. Its<br />

chunky heatsinks and simple but rugged<br />

build-quality give an accurate indication<br />

of the solid sound this little behemoth<br />

produces. The Panache has been around<br />

for about two years and is sold exclusively<br />

via Portal’s Web site (www.portalaudio.com)<br />

for $1795—not bad for a 100<br />

watt/channel amplifier whose guarantee<br />

includes a sixty-day return policy. As<br />

Henry Ford used to say about his Model<br />

A, you can have the Panache in any color<br />

you’d like as long as it’s black. The front<br />

of the unit is rather simple, providing<br />

only an input selector switch, a balance<br />

knob, a volume knob, and a headphone<br />

socket. The rear of the unit has a stereo<br />

pair of five-way binding posts, four pairs<br />

of analog inputs, and a pair of analog<br />

recording outputs.<br />

Finding an amplifier able to play<br />

loud was very important to me, and the<br />

Panache delivered the goods without<br />

breaking a sweat. To show why volume<br />

really matters, let me tell you about an<br />

extremely catchy song that has been<br />

buzzing through my cranium for some<br />

time now—and really needs to be played<br />

loudly. Yes folks, I’m talking about “I<br />

24 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

Believe in a Thing Called Love” from<br />

Permission to Land [Atlantic] by The<br />

Darkness. This song is full of crunchy<br />

guitars and 1980s hair-band kitsch. The<br />

beginning of the song starts with the<br />

main riff, full of distortion, played at<br />

very low level for two bars; then in the<br />

third bar, a bass, kick, and snare drum<br />

snap into action with such head-rockin’<br />

loudness and good soundstaging that I<br />

felt like I was sitting in front of a 12-foot<br />

stack of Marshall amps (although when I<br />

checked, the volume of the Panache was<br />

only set at 25%). Powered by the<br />

Panache, the rhythm and pacing—that<br />

is, transients and dynamics—of the<br />

music sounded spectacular, progressing<br />

from the quietest to the loudest passages<br />

without losing detail. I wanted an amp<br />

that didn’t lose clarity, resolution, or<br />

dynamic impact at any volume level, and<br />

I found what I wanted in the Panache.<br />

Simple is as simple gets, and from<br />

this no-frills amp I mostly got just what<br />

I wanted. What might have made it<br />

even more enjoyable, however, would<br />

have been a remote. I hope I’m not being<br />

too picky here, but I do appreciate being<br />

able to select inputs as well as adjust volume<br />

levels from my couch (these are<br />

basic control functions many audiophiles<br />

want to have when auditioning<br />

music). While not fancy, the amplifier<br />

that pleases me has to deliver all the<br />

essentials right, and this the Portal does<br />

magnificently.<br />

Completing my system was a pair of<br />

$1598 Definitive Technology BP7004<br />

loudspeakers, smaller versions of the<br />

BP7002 SuperTowers (note, though,<br />

that they are “smaller” relative to the<br />

very big sound and value that all members<br />

of the SuperTower speaker family<br />

seem to offer). The BP7004 features<br />

bipolar driver arrays (with identical sets<br />

of forward- and rear-facing drivers)<br />

incorporating two 5" bass/midrange<br />

drivers with cast-basket frames and two<br />

1" aluminum-dome tweeters. The bass<br />

section of the speaker provides a built-in<br />

powered subwoofer that consists of a 10"<br />

driver and two 10" pressure-driven<br />

“infrasonic” passive radiators, powered<br />

by a 300-watt internal amplifier.<br />

Whatever I chose to throw at these<br />

speakers, I was always able to hear something<br />

good that I hadn’t heard before—<br />

especially in the bottom octaves. Can<br />

you say FUN? Couple the Def Techs<br />

with the high-resolution Philips player<br />

and the potent Portal Panache, which is<br />

more than able to push the speakers<br />

with oomph and clarity, and you’ve got<br />

a perfect three-way combo.<br />

The tonal balance of the BP7004s<br />

was very impressive. Because the<br />

WWW.THEABSOLUTESOUND.COM 25

BP7004s are bipolar loudspeakers,<br />

music emanates from both the front and<br />

back, resulting, IMO, in a much more<br />

realistic image. On Michael Jackson’s<br />

Thriller [Sony], the “Billie Jean” track<br />

starts with a simple kick and snare and<br />

evolves into the complex tapestry of an<br />

eight-note bass line accompanied by a<br />

funky guitar lick—a simple yet effective<br />

passage that the Definitives cleanly execute.<br />

The guitar had a clean tone that<br />

sounded very realistic, the kick and<br />

snare both sounded accurate, and<br />

Michael’s voice was extraordinarily clear<br />

and transparent—so much so, in fact,<br />

that I could hear his inhalations between<br />

each line, something I had never noticed<br />

in previous listening sessions.<br />

So much of rock and hip-hop can be<br />

drowned out by speakers with a sloppy<br />

low-end—speakers that sacrifice accurate<br />

mids and highs to achieve the thun-<br />

derous low “drone” you hear from many<br />

car stereo systems. These poorly<br />

designed speakers are designed around a<br />

couple of music styles only, so if you try<br />

to play something outside the standard<br />

hip-hop repertoire, you’ll hear the same<br />

bass-heavy EQ curve etched onto your<br />

music. Although I once was an example<br />

of a bass-driven enthusiast, I have since<br />

discovered there is much more going on<br />

in the high frequencies and midrange<br />

than I first realized.<br />

For me, the initial discovery came<br />

through Red Rose Music’s Spirit loudspeaker—a<br />

speaker I really dig for its<br />

clean, upfront presentation, vivid soundstage<br />

and imaging, and extremely transparent<br />

mids and highs. But as I looked<br />

back, the Spirit’s upfront presentation<br />

was sometimes too aggressive, creating<br />

an imbalance in the sound and becoming<br />

fatiguing in the long run. The BP<br />

7004 is much different, successfully<br />

delivering warm mids and highs, and<br />

always managing to sound engaging<br />

(and certainly not fatiguing). On<br />

Lovage’s Music to Make Love to Your Old<br />

Lady By [Tommy Boy], the “Anger<br />

Management” track sent shivers down<br />

my spine with its mix of jazz and<br />

lounge-bar theatrics rolled up into a<br />

hip-hop tortilla. The beat supplied by<br />

Kid Koala is a simple, jazzy kick/snare<br />

combination brought to life by the<br />

BP7004’s not overly bright, yet always<br />

warm and airy midrange. In the song’s<br />

main chorus, this beat is coupled with<br />

the sound of Mike Patton and Jennifer<br />

Charles’ duet, and the top octaves of<br />

their voices are absolutely stunningly<br />

revealed by the tweeter. Mike’s voice<br />

(often called an instrument in itself), is<br />

complemented by Charles’ upper range,<br />

creating a third, more complex voicing<br />

26 THE ABSOLUTE SOUND ■ JUNE/JULY 2004

that is simply phenomenal.<br />

I’m sometimes disappointed to find<br />

a really good loudspeaker that performs<br />

in the mid- and high-frequency departments,<br />

yet doesn’t have balls in the bass.<br />

The BP7004s combine a fantastic middle<br />

and high section with a built-in subwoofer,<br />

so there’s no need to even think<br />

about spending more money on a sub.<br />

The BP 7004s have tonally accurate bass<br />

that’s bound to shake yer rump—low<br />

end that will cause your neighbors to<br />

either envy you or want to puncture<br />

your speaker cones with a screwdriver.<br />

Chuck D. from Public Enemy said it<br />

best, “Bass! How low can you go!” Well,<br />

Mr. D, these speakers are “the bomb!” I<br />

appreciated being able to adjust the subwoofer<br />

level to tune the speaker’s bass<br />

output to fit the requirements of whatever<br />

song I wanted to hear. What fun!<br />

The “Murderers” cut from John<br />

Frusciante’s To Record Only Water for Ten<br />

Days [Warner Brothers] shows you just<br />

how much fun you can have with an<br />

adjustable subwoofer level control. The<br />

song starts off with a programmed beat<br />

that quickly leads to the opening riff.<br />

You can listen to this song five times in<br />

a row and each time hear something different;<br />

when you push the subwoofer to<br />

go lower and louder, the beat gets more<br />

interesting each time, yet it never distracts<br />

you from the amazing textural<br />

tapestry that Frusciante’s weaves with<br />

each electric guitar note. Tonally accurate<br />

bass is always available to you, but I<br />

often found it cooler to fatten up the<br />

lower end at least a bit. From accurate<br />

mids and highs to a deep satisfying low<br />

end, this speaker did it all for me.<br />

Taken as individual components, the<br />

Philips DVD963SA, Portal Panache,<br />

and Definitive Technology BP7004s are<br />

all good performers within their respective<br />

product classes and price ranges, but<br />

taken as a whole this system performs at<br />

a level much higher that the sum of its<br />

parts. But don’t feel compelled to stick<br />

with this system (unless you want to);<br />

start piecing together your own dream<br />

hi-fi to fit your personal budget and<br />

musical tastes. No one is wrong in this<br />

game and musical enjoyment in the end<br />

boils down to what you want out of your<br />

stereo—not what a dealer (or an audio<br />

magazine) tells you your music is supposed<br />

to sound like. As for me, I’ll take<br />

a system whose affordable components<br />

are synergistically matched over poorly<br />

matched combinations of pricier equipment<br />

any day of the week! &<br />

SPECIFICATIONS<br />

Definitive Technology BP7004 loudspeaker<br />

w/300-watt internal subwoofer amplifier<br />

Driver Complement: Two 5.25" bass/mid<br />

drivers, two 1" aluminum-dome tweeters,<br />

10" active subwoofer driver, two 10" passive<br />

radiators<br />

Frequency Response: 16Hz–30kHz<br />

Sensitivity: 92dB<br />

Impedance: 8 ohms<br />

Recommended Amplifier Power: 20–300Wpc<br />

Dimensions: 6.6" x 42.25" x 13"<br />

Price: $1598/pair<br />

Philips DVD963SA DVD/SACD player<br />

Outputs: Component, composite, S-video,<br />

RGB<br />

Dimensions: 17" x 3" x 10"<br />

Weight: 8 lbs.<br />

Price: $499<br />

Portal Panache Integrated Amp<br />

Power output: 100 watts/channel at 8 ohms;<br />

200 watts/channel at 4 ohms<br />

Inputs: Four line-level<br />

Dimensions: 17" x 4.5" x 12"<br />

Weight: 33 lbs.<br />

Price: $1795<br />

ASSOCIATED EQUIPMENT<br />

Wireworld Speaker Cables, Monster Cable<br />

Interconnects, Chang Lightspeed CLS 3200<br />

Power Conditioner, M-Audio Audiophile<br />

24/96 <strong>Sound</strong>card<br />

MANUFACTURER INFORMATION<br />

DEFINITIVE TECHNOLOGY<br />

11433 Cronridge Drive Suite K<br />

Owings Mills, Maryland 21117<br />

(410) 363-7148<br />

www.definitivetech.com<br />

PHILIPS ELECTRONICS<br />

64 Perimeter Center East<br />

Atlanta, Georgia 30346<br />

(865) 521-4316<br />

www.philips.com<br />