WfHC - cover page (not to be used with pre-printed report ... - CSIRO

WfHC - cover page (not to be used with pre-printed report ... - CSIRO

WfHC - cover page (not to be used with pre-printed report ... - CSIRO

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

T<br />

Working Knowledge: local ecological and hydrological knowledge<br />

about the flooded forest country of Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

Marcus Bar<strong>be</strong>r, Jeff Shell<strong>be</strong>rg, Sue Jackson and Viv Sinnamon<br />

Septem<strong>be</strong>r 2012<br />

Featuring information from the Oriners Mob at Kowanyama, Forest People from<br />

central Cape York, the Hughes family and former Oriners Station cattlemen.

Water for a Healthy Country Flagship Report<br />

Australia is founding its future on science and innovation. Its national science agency, <strong>CSIRO</strong>, is a<br />

powerhouse of ideas, technologies and skills.<br />

<strong>CSIRO</strong> initiated the National Research Flagships <strong>to</strong> address Australia‟s major research challenges<br />

and opportunities. They apply large scale, long term, multidisciplinary science and aim for wides<strong>pre</strong>ad<br />

adoption of solutions. The Flagship Collaboration Fund supports the <strong>be</strong>st and brightest researchers <strong>to</strong><br />

address these complex challenges through partnerships <strong>be</strong>tween <strong>CSIRO</strong>, universities, research<br />

agencies and industry.<br />

The Water for a Healthy Country Flagship aims <strong>to</strong> provide Australia <strong>with</strong> solutions for water resource<br />

management, creating economic gains of $3 billion per annum by 2030, while protecting or res<strong>to</strong>ring<br />

our major water ecosystems. The work contained in this <strong>report</strong> is collaboration <strong>be</strong>tween <strong>CSIRO</strong>, the<br />

National Water Commission, and the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population<br />

and Communities.<br />

For more information about Water for a Healthy Country Flagship or the National Research Flagship<br />

Initiative visit www.csiro.au/org/HealthyCountry.html<br />

Citation: Bar<strong>be</strong>r, M., Shell<strong>be</strong>rg, J., Jackson, S and Sinnamon, V. (2012). Working<br />

Knowledge: local ecological and hydrological knowledge about the flooded forest country of<br />

Oriners Station, Cape York. <strong>CSIRO</strong>, Darwin.<br />

ISBN: 978-0-643-108851 (WEB)<br />

Copyright and Disclaimer:<br />

© 2012 <strong>CSIRO</strong> To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication<br />

<strong>cover</strong>ed by copyright may <strong>be</strong> reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except <strong>with</strong> the<br />

written permission of <strong>CSIRO</strong>.<br />

Important Disclaimer:<br />

<strong>CSIRO</strong> advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based<br />

on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> aware that such information may <strong>be</strong><br />

incomplete or unable <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> <strong>used</strong> in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore <strong>be</strong><br />

made on that information <strong>with</strong>out seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To<br />

the extent permitted by law, <strong>CSIRO</strong> (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability <strong>to</strong><br />

any person for any consequences, including but <strong>not</strong> limited <strong>to</strong> all losses, damages, costs, expenses<br />

and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in<br />

whole) and any information or material contained in it.<br />

This <strong>report</strong> was jointly funded and published by the National Water Commission and the Department<br />

of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. The views and opinions<br />

ex<strong>pre</strong>ssed in this publication are those of the authors and do <strong>not</strong> necessarily reflect those of the<br />

Australian Government or the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and<br />

Communities. While reasonable efforts have <strong>be</strong>en made <strong>to</strong> ensure that the contents of this publication<br />

are factually correct, the Commonwealth does <strong>not</strong> accept responsibility for the accuracy or<br />

completeness of the contents, and shall <strong>not</strong> <strong>be</strong> liable for any loss or damage that may <strong>be</strong> occasioned<br />

directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication.<br />

Enquiries:<br />

Dr Marcus Bar<strong>be</strong>r<br />

<strong>CSIRO</strong> Ecosystem Sciences<br />

PMB 44 Winnellie NT 0822<br />

Phone: 08 8944 8420<br />

Email: Marcus.Bar<strong>be</strong>r@csiro.au<br />

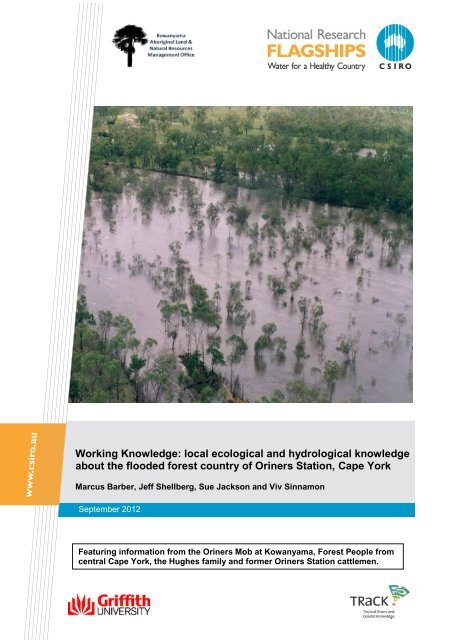

Cover Pho<strong>to</strong>graph: Eight Mile Creek in flood. Image © KALNRMO. Unless otherwise indicated, all<br />

figures and pho<strong>to</strong>graphs in this <strong>report</strong> are © 2012 <strong>CSIRO</strong>.<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

ii

CONTENTS<br />

Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................... xi<br />

LIst of Abbreviations ................................................................................................ xii<br />

Executive summary ................................................................................................. xiii<br />

1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1<br />

1.1 Working Knowledge .................................................................................................. 1<br />

1.2 Flooded forest country at Oriners Station ................................................................. 4<br />

1.3 Forest People and the Oriners Mob .......................................................................... 6<br />

1.4 Research methods and participants ......................................................................... 7<br />

1.4.1 Research methods ................................................................................................ 7<br />

1.4.2 Research participants ............................................................................................ 7<br />

1.5 Existing archival resources ....................................................................................... 8<br />

1.5.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 8<br />

1.5.2 Natural scientific resources.................................................................................... 9<br />

1.5.3 Cultural, linguistic, his<strong>to</strong>rical and ethnographic resources ................................... 10<br />

1.6 His<strong>to</strong>ry of Oriners Station ........................................................................................ 19<br />

1.6.1 The <strong>pre</strong>-colonial period ........................................................................................ 19<br />

1.6.2 The Hughes Family ............................................................................................. 19<br />

1.6.3 The Finches at Sef<strong>to</strong>n ......................................................................................... 21<br />

1.6.4 Indigenous cattlemen .......................................................................................... 21<br />

1.6.5 Oriners purchase and recent his<strong>to</strong>ry .................................................................... 23<br />

1.7 Oriners and the contemporary regional NRM context ............................................ 32<br />

1.8 Summary ................................................................................................................. 35<br />

2 Interview <strong>to</strong>pics and themes: environmental and landscape processes ..... 37<br />

2.1 Variability and Change ............................................................................................ 37<br />

2.1.1 Geographic variability: Oriners regional comparisons ......................................... 37<br />

2.1.2 Inter-annual variability – weather and flood levels ............................................... 44<br />

2.1.3 „This month is different‟: abnormal changes ........................................................ 45<br />

2.1.4 Seasonal signals ................................................................................................. 47<br />

2.2 Water....................................................................................................................... 49<br />

2.2.1 Rain ..................................................................................................................... 49<br />

2.2.2 Flood levels and drainage lines at Oriners .......................................................... 51<br />

2.2.3 Regional flooding- the Eight Mile and Crosbie Creeks ........................................ 57<br />

2.2.4 Permanent water and groundwater flow .............................................................. 64<br />

2.2.5 Water quality........................................................................................................ 67<br />

2.3 Native animals ........................................................................................................ 69<br />

2.3.1 Aquatic animals ................................................................................................... 69<br />

2.3.2 Birds .................................................................................................................... 72<br />

2.3.3 Native <strong>pre</strong>da<strong>to</strong>rs: dingoes .................................................................................... 75<br />

2.3.4 Wallabies ............................................................................................................. 77<br />

2.4 Introduced animals .................................................................................................. 77<br />

2.4.1 Cattle ................................................................................................................... 78<br />

2.4.2 Pigs ..................................................................................................................... 79<br />

2.4.3 Horses ................................................................................................................. 81<br />

2.4.4 Cane <strong>to</strong>ads .......................................................................................................... 82<br />

2.5 Human activity ........................................................................................................ 85<br />

2.5.1 Pre-colonial wet season residence and subsistence ........................................... 85<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

iii

2.5.2 Access, infrastructure and residence ................................................................... 86<br />

2.5.3 Bush food at Oriners ............................................................................................ 91<br />

2.5.4 Cattlemen: working connections .......................................................................... 94<br />

2.5.5 Old and new connections .................................................................................... 95<br />

2.5.6 Tourists and trespassers ..................................................................................... 98<br />

2.5.7 Resources and funding ...................................................................................... 101<br />

2.6 Landscape processes and human and animal distributions ................................. 103<br />

2.6.1 Water and animal distributions .......................................................................... 103<br />

2.6.2 Cattle mustering patterns .................................................................................. 105<br />

2.6.3 Fire regimes....................................................................................................... 109<br />

2.6.4 Erosion .............................................................................................................. 114<br />

2.7 Additional features of knowledge about Oriners ................................................... 121<br />

2.7.1 Applying „Working Knowledge‟ .......................................................................... 122<br />

2.7.2 Linguistic classifications and categories ............................................................ 123<br />

2.7.3 Correlations and causes .................................................................................... 127<br />

3 Local scientific knowledge ........................................................................... 131<br />

3.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 131<br />

3.2 Physical conditions ............................................................................................... 131<br />

3.2.1 Climate .............................................................................................................. 131<br />

3.2.2 Topography and drainage ................................................................................. 134<br />

3.2.3 Geology ............................................................................................................. 135<br />

3.2.4 Soils ................................................................................................................... 138<br />

3.2.5 Land systems .................................................................................................... 140<br />

3.2.6 Soil erosion ........................................................................................................ 146<br />

3.2.7 Catchment land use ........................................................................................... 146<br />

3.2.8 Surface hydrology .............................................................................................. 148<br />

3.2.9 Hydrogeology .................................................................................................... 151<br />

3.2.10 Fluvial geomorphology of the Eight Mile Creek near Oriners Lagoon ................ 153<br />

3.2.11 Gully erosion...................................................................................................... 165<br />

3.3 Biological conditions ............................................................................................. 171<br />

3.3.1 Forest <strong>cover</strong>....................................................................................................... 171<br />

3.3.2 Grass <strong>cover</strong> ....................................................................................................... 172<br />

3.3.3 Weeds ............................................................................................................... 172<br />

3.3.4 Fire timing, frequency, and distribution .............................................................. 173<br />

3.3.5 Feral animals and s<strong>to</strong>ck ..................................................................................... 177<br />

3.3.6 Native terrestrial animals ................................................................................... 178<br />

3.3.7 Native birds........................................................................................................ 179<br />

3.3.8 Native aquatic animals ...................................................................................... 179<br />

3.4 Oriners and Forest Country – a brief personal perspective .................................. 180<br />

4 Synthesis: process and relationship models .............................................. 183<br />

4.1 Models of landscape-scale ecological, hydrological, and geomorphological relations at<br />

Oriners Station ...................................................................................................... 184<br />

4.1.1 Wet season........................................................................................................ 184<br />

4.1.2 Early dry season ................................................................................................ 186<br />

4.1.3 Late dry season ................................................................................................. 188<br />

4.1.4 Comparisons and interactions across seasons ................................................. 188<br />

4.1.5 Impact of Oriners Mob residence ....................................................................... 189<br />

4.2 Models of processes affecting Oriners and Jewfish Lagoons .............................. 190<br />

4.2.1 Model Introduction ............................................................................................. 190<br />

4.2.2 Oriners Lagoon .................................................................................................. 191<br />

4.2.3 Jewfish Lagoon .................................................................................................. 192<br />

4.2.4 Other major lagoons – Mosqui<strong>to</strong> and Horseshoe .............................................. 194<br />

4.3 Water quality ......................................................................................................... 196<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

iv

5 Working knowledge: Conclusions and recommendations ......................... 197<br />

5.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 197<br />

5.2 Flooded forest country – key characteristics ........................................................ 198<br />

5.3 Future plans and aspirations ................................................................................ 201<br />

5.4 Recommendations for further research ................................................................ 202<br />

5.5 Conclusion ............................................................................................................ 204<br />

6 References ..................................................................................................... 205<br />

7 Glossary ......................................................................................................... 212<br />

8 Appendices .................................................................................................... 218<br />

8.1 Informed Consent Form ........................................................................................ 218<br />

8.2 Seasonal indica<strong>to</strong>r observations ........................................................................... 219<br />

8.3 Wildlife Animal Species List for the Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n Area............................... 220<br />

8.4 Plant Species List for the Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n Area .............................................. 225<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

v

FIGURES<br />

Figure 1. Watercourse of Eight Mile Creek. ........................................................................... xi<br />

Figure 2. Mitchell River catchment <strong>with</strong> Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n Stations in the Alice River<br />

subcatchments. .......................................................................................................... xv<br />

Figure 3. Cattle stations in lower Mitchell River catchment, <strong>with</strong> outlines of Kowanyama<br />

managed lands (red) including Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n Stations. ........................................ 2<br />

Figure 4. Map of the lower Eight Mile and Crosbie Creek valleys and locations of the 4 major<br />

lagoons discussed in the <strong>report</strong>: Oriners, Mosqui<strong>to</strong>, Jewfish and Crosbie. .................... 5<br />

Figure 5. Horseshoe Lagoon. ............................................................................................... 11<br />

Figure 6. Cecil Hughes in Mareeba, July 2012. .................................................................... 20<br />

Figure 7. David Hughes speaking at a Mitchell River workshop attended by KALNRMO staff<br />

during the early 1990s. Image © KALNRMO............................................................... 24<br />

Figure 8. David and Bill Hughes negotiating the sale <strong>with</strong> Kowanyama people. Image ©<br />

KALNRMO .................................................................................................................. 25<br />

Figure 9. Planning meeting at Oriners soon after the purchase. Image © KALNRMO .......... 26<br />

Figure 10. Shed construction team, Oriners station. Image © KALNRMO ............................ 27<br />

Figure 11. Cattle yards at Oriners Station. Image © KALNRMO .......................................... 28<br />

Figure 12. Oriners house during construction. Image © KALNRMO ..................................... 29<br />

Figure 13. Oriners house from the air in 2012. ..................................................................... 30<br />

Figure 14. Paddy Yam, Philip Yam, Ravin Greenwool and his son Delvin at the Oriners<br />

house in 2011. ............................................................................................................ 31<br />

Figure 15. Billabong downstream from Oriners Homestead. ................................................ 41<br />

Figure 16. Paddy Yam and Louie Native standing next <strong>to</strong> Grevillea pteridifolia in flower at<br />

Mosqui<strong>to</strong> Lagoon. ....................................................................................................... 47<br />

Figure 17. Philip Yam <strong>with</strong> woody debris wedged by flood at Eight Mile Creek. ................... 51<br />

Figure 18. Oriners homestead area in flood ©KALNMRO .................................................... 52<br />

Figure 19. Philip Yam and Louie Native talk <strong>to</strong> Jeff Shell<strong>be</strong>rg about flow patterns at Oriners.<br />

................................................................................................................................... 55<br />

Figure 20. Oriners Lagoon in flood ©. KALNRMO ................................................................ 56<br />

Figure 21. Flooded Oriners airstrip.©KALNRMO .................................................................. 56<br />

Figure 22. Flood level on trees downstream from Oriners homestead. ................................ 57<br />

Figure 23. Large Woody Debris (LWD) deposited during flood on the Eight Mile Creek. ...... 58<br />

Figure 24. Jeff Shell<strong>be</strong>rg talks <strong>with</strong> Philip Yam, Louie Native, and Viv Sinnamon about<br />

erosion and water flow along the Eight Mile Creek at Oriners. .................................... 60<br />

Figure 25. Oriners country in flood. Image © KALNRMO ..................................................... 61<br />

Figure 26. Flooded forest at Oriners. Image © KALNRMO ................................................... 61<br />

Figure 27. Mitchell catchment in flood – Errk Oykangand National Park. Image © KALNRMO<br />

................................................................................................................................... 62<br />

Figure 28. Mitchell catchment in the wet season. Image © KALNRMO ................................ 62<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

vi

Figure 29. Mitchell catchment in flood – Errk Oykangand National Park. Image © KALNRMO.<br />

................................................................................................................................... 63<br />

Figure 30. Oriners country in flood. Image © KALNRMO ..................................................... 63<br />

Figure 31. Oriners Lagoon looking upstream. ...................................................................... 66<br />

Figure 32. Pig damage at Oriners. ....................................................................................... 80<br />

Figure 33. Erosion damage at old Oriners airstrip. ............................................................... 89<br />

Figure 34. Fish from Oriners Lagoon. .................................................................................. 91<br />

Figure 35. Philip Yam talks <strong>to</strong> mo<strong>to</strong>rcycle <strong>to</strong>urists passing through Oriners ......................... 98<br />

Figure 36. Fire damage <strong>to</strong> Oriners cattle yards in the 1990s. Image © KALNRMO .............. 99<br />

Figure 37. Old s<strong>to</strong>ckman‟s quarters <strong>with</strong> eroding foundations. ........................................... 102<br />

Figure 38. Oriners station from the air looking east circa 1990, showing older road networks.<br />

Image © KALNRMO ................................................................................................. 118<br />

Figure 39. Oriners station and lagoon from the air looking west circa 2012. ....................... 118<br />

Figure 40. Oriners station and building from the air looking east circa 2012. ...................... 119<br />

Figure 41. Cleared zone for new road through Oriners. ..................................................... 120<br />

Figure 42. Giant long-armed prawn, Macrobrachium rosen<strong>be</strong>rgii (image: P. Hamil<strong>to</strong>n) ...... 123<br />

Figure 43. North Queensland yabby or redclaw, Cherax quadricarinatus (Image: P. Hamil<strong>to</strong>n)<br />

................................................................................................................................. 124<br />

Figure 44. Average monthly rainfall at Oriners Station and nearby stations <strong>with</strong> longer<br />

records of rainfall and temperature. .......................................................................... 132<br />

Figure 45. Daily rainfall <strong>to</strong>tals at Oriners Station 1963-1970. .............................................. 133<br />

Figure 46. Long-term annual WY rainfall <strong>to</strong>tals and trends at Koolatah and Musgrave. ...... 134<br />

Figure 47. Topography and drainage of the catchments surrounding Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n<br />

Stations. Elevation data derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission 30m pixel<br />

digital elevation model (SRTM 2000). ....................................................................... 135<br />

Figure 48. Geology of the catchments surrounding Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n Stations. Note<br />

locations of abandoned mines. ................................................................................. 136<br />

Figure 49. Soils of Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n Stations based on the original “Atlas of Australian<br />

Soils” (Is<strong>be</strong>ll et al. 1968; BRS 1991). ........................................................................ 140<br />

Figure 50. Land system of the forest country around Oriners/Sef<strong>to</strong>n Stations. Balurga (Ba);<br />

Mottle (Mo); Annaly (A); Cumbulla (C) (extracted from Galloway et al. 1970). ......... 140<br />

Figure 51. Balurga (Ba) land system. Extensive plains on weather terrestrial sediment; sandy<br />

red and yellow earths and uniform sandy soils; bloodwood-stringybark woodland, and<br />

some paperbark woodland. (Galloway et al. 1970). .................................................. 141<br />

Figure 52. RAAF oblique pho<strong>to</strong>graph from 1943 of the Balurga (Ba) land system near Sef<strong>to</strong>n<br />

and Oriners Stations. ................................................................................................ 142<br />

Figure 53. Mottle (Mo) land system. Extensive plains on weathered terrestrial sediments,<br />

silts<strong>to</strong>ne, and alluvium; massive earths; paperbark or bloodwood-stringybark woodland<br />

(Galloway et al. 1970). .............................................................................................. 143<br />

Figure 54. Annaly (A) land system. Lowlands on partially dissected terrestrial sediment over<br />

shale massive earths and texture-contrast soils; paperbark or bloodwood-stringybark<br />

woodland. (Galloway et al. 1970). ............................................................................ 144<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

vii

Figure 55. Cumbulla (C) land system. Alluvial plains in part actively forming and largely<br />

flooded in the wet season; texture-contrast soils; paperbark woodland (Galloway et al.<br />

1970). ....................................................................................................................... 145<br />

Figure 56. Land use map of the Mitchell catchment showing a) operating mines, abandoned<br />

mines, mine claims, proposed mines, b) distribution of major alluvial gullies, c) major<br />

paved and unpaved roads, d) existing and proposed water resource development, e)<br />

agricultural development near Dimbulah (green outline). Note the relatively sparse<br />

development in and around Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n Stations. ......................................... 148<br />

Figure 57. Minimum flood inundation frequency data for Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n Stations and part<br />

of the Mitchell fluvial megafan (MODIS satellite imagery, num<strong>be</strong>r of times inundated<br />

<strong>be</strong>tween 2003 and 2009; Ward et al. 2012). Major permanent water body locations and<br />

typical dry-season water clarity estimates from Landsat satellite data (1986 and 2005)<br />

are also shown (Lymburner and Burrows 2008), as are the locations of smaller<br />

intermittent palustrine wetlands are also shown in black (Queensland Department of<br />

Natural Resources (QDERM) 2010).......................................................................... 149<br />

Figure 58. Air pho<strong>to</strong>graph of a mound spring (white) areas on Oriners Station. ................. 152<br />

Figure 59.Pho<strong>to</strong>graphs of a mound spring on western Oriners Station <strong>with</strong> a) water seeping<br />

<strong>to</strong> the surface, b) fluid muds oozing <strong>to</strong> the surface under <strong>pre</strong>ssure, c) the pebble lags of<br />

gravel and ferricrete nodules on the spring surface, and d) sheet wash deposit on <strong>to</strong>p<br />

of the spring following wet season rain-fall runoff or groundwater discharge. ............ 153<br />

Figure 60. False colour satellite image (ASTER) of the river segment and landscape<br />

surrounding Oriners Station and Eight Mile Creek. Note bright red colour is riparian<br />

vegetation (mainly Melaleuca spp.) growing along Eight Mile Creek. Inset box refers <strong>to</strong><br />

air pho<strong>to</strong>graphs in Figure 64 and Figure 65. ............................................................. 154<br />

Figure 61. Digital elevation model of the river segment and landscape surrounding Oriners<br />

Station and Eight Mile Creek using the 30m pixel data from the Shuttle Radar<br />

Topography Mission (SRTM 2000). Inset box refers <strong>to</strong> air pho<strong>to</strong>graphs in Figure 64 and<br />

Figure 65. Cross-section lines refer <strong>to</strong> data in Figure 62. .......................................... 155<br />

Figure 62. Elevation cross-sections across the Eight Mile Creek Valley at Oriners, derived<br />

from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission 30m pixel digital elevation model (SRTM<br />

2000). Cross-section locations are mapped in Figure 61. Note that 2 <strong>to</strong> 5 m fluctuations<br />

in elevation could <strong>be</strong> errors from vegetation artefacts in the data. ............................. 155<br />

Figure 63. Longitudinal profile of the Eight Mile Creek Valley from the confluence of Crosbie<br />

Creek <strong>to</strong> the headwaters derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission 30m pixel<br />

digital elevation model (SRTM 2000). The Oriners segment of Eight Mile Creek is also<br />

mapped in Figure 61. ................................................................................................ 156<br />

Figure 64. 1955 Aerial Pho<strong>to</strong>graph of the Eight Mile Creek reach near Oriners Station and<br />

Lagoon. See Figure 67 for detail of inset box. ........................................................... 158<br />

Figure 65. 2004 Aerial Pho<strong>to</strong>graph of the Eight Mile Creek reach near Oriners Station and<br />

Lagoon, showing existing (<strong>pre</strong>-2004) and new road (2010) infrastructure, air strip and<br />

gully erosion problem areas. See Figure 68 for detail of inset box. ........................... 158<br />

Figure 66. Ground pho<strong>to</strong>s during July 2011 of a) Eight Mile Creek looking upstream near the<br />

main anabranch bifurcation that feeds Oriners Lagoon, <strong>not</strong>e major sand bar deposits<br />

that influence channel divergence and anabranching, b) Eight Mile Creek looking<br />

upstream <strong>be</strong>low the main anabranch bifurcation that feeds Oriners Lagoon, c) the main<br />

anabranch channel looking downstream that feeds Oriners Lagoon, and d) the smaller,<br />

most upstream, anabranch channel looking downstream that feeds Oriners Lagoon.159<br />

Figure 67. 1955 Aerial Pho<strong>to</strong>graph Oriners Station and Lagoon. Note new road in 1955. .. 162<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

viii

Figure 68. 2004 Aerial Pho<strong>to</strong>graph of Oriners Station and Lagoon, showing existing road<br />

infrastructure and gully erosion problem areas. ........................................................ 162<br />

Figure 69. Ground pho<strong>to</strong>s during July 2011 of a) a sand bar infilling the <strong>to</strong>p end of Oriners<br />

Lagoon, b) the same sand bar at distance <strong>with</strong> colonizing vegetation, c), bank erosion<br />

and adjacent sand bar along the main anabranch channel above Oriners Lagoon, d)<br />

similar anabranch bank erosion and sand splay on<strong>to</strong> the floodplain above Oriners<br />

Lagoon, e) general sheet and gully erosion along the road crossing the upper<br />

anabranch inlet <strong>to</strong> Oriners Lagoon, and f) the same eroded anabranch channel looking<br />

upstream from the road. ............................................................................................ 163<br />

Figure 70. Ground pho<strong>to</strong>s of the Oriners Lagoon outlet a) in 1997 looking north <strong>with</strong> active<br />

road across outlet and sparse woodlands and emergent Melaleuca trees on sill, b) in<br />

July 2011 looking south <strong>with</strong> denser stands of Melaleuca trees, c) in July 2011 looking<br />

upstream at eroded cut through the sill on the southern outlet, d) in July 2011 looking<br />

upstream at the southern outlet channel eroding upstream <strong>to</strong>ward the sill and cut, e) in<br />

~1990 looking upstream at the sill on the northern outlet, and f) in July 2011 looking<br />

upstream at an incipient cut that will eventually erode through the sill on the northern<br />

outlet; <strong>not</strong>e same tire hanging from tree in e and f. ................................................... 164<br />

Figure 71. Examples of alluvial gullies on lagoon banks at a) Oriners Lagoon, b) Jewfish<br />

Lagoon, c) road/track at Jewfish Lagoons feeding water in<strong>to</strong> a gully, which is the same<br />

as d) next <strong>to</strong> Jewfish Lagoon. ................................................................................... 168<br />

Figure 72. A large gully upstream of Oriners Lagoon triggered by the road crossing the<br />

lagoons inlet drainage ways. ..................................................................................... 168<br />

Figure 73. Examples of roads/tracks that have cut in<strong>to</strong> the Eight Mile floodplain creating<br />

linear alluvial gullies: a) the western road entrance <strong>to</strong> Oriners, b) the eastern entrance<br />

<strong>to</strong> Oriners, c) an intact road segment on the eastern road, d) a gullied road segment<br />

downstream of c on the eastern road, e) the gullied airplane strip at Oriners from the<br />

ground, and f) the gullied airplane strip and adjacent road/fenceline at Oriners from the<br />

air. ............................................................................................................................ 169<br />

Figure 74. Examples of potential impacts from new road construction through Oriners Station<br />

and bypassing the Oriners homestead: a) the new cleared bypass viewed from the air,<br />

b) the new cleared bypass crossing an intact swampy drainage way (dambo) viewed<br />

from the air, c) the same intact swampy drainage way (dambo) viewed from the<br />

ground, d) a similar nearby drainage way that has <strong>be</strong>en gullied from excess road<br />

runoff, e) the new bypass road clearing and initial gully erosion by subsequent wet<br />

seasons, and f) a new constructed road prism <strong>with</strong> continued delivery of road ditch<br />

sediment and concentrated water <strong>to</strong> a local creek, in addition <strong>to</strong> the s<strong>pre</strong>ad of grader<br />

grass and other weeds.............................................................................................. 170<br />

Figure 75. Annual fire frequency of all seasonal fires for the Oriners/Sef<strong>to</strong>n area <strong>be</strong>tween<br />

1997 and 2010. Dark red <strong>to</strong> purple area re<strong>pre</strong>sent frequent fires occurring 10 year out<br />

of 14 <strong>to</strong>tal. Data are from the Northern Australia Fire Information (NAFI) website<br />

(www.firenorth.org.au). ............................................................................................. 175<br />

Figure 76. Annual fire frequency of late-season fires for the Oriners/Sef<strong>to</strong>n area <strong>be</strong>tween<br />

1997 and 2010. Dark red <strong>to</strong> purple area re<strong>pre</strong>sent frequent late-season fires occurring<br />

10 year out of 14 <strong>to</strong>tal, <strong>with</strong> a similar pattern and frequency <strong>to</strong> all fires in Figure 75.<br />

Data are from the Northern Australia Fire Information (NAFI) website<br />

(www.firenorth.org.au). ............................................................................................. 175<br />

Figure 77. 1955 aerial pho<strong>to</strong>graph of the Eight Mile Creek floodplain and grassy woodlands<br />

1000m south of the Oriners Station Air Strip. Compare <strong>to</strong> Figure 78. ........................ 176<br />

Figure 78. 2004 air pho<strong>to</strong>graph of the Eight Mile Creek floodplain and grassy woodlands<br />

1000m south of the Oriners Station Airstrip. Note woodland thickening around<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

ix

vegetation corridors compared <strong>to</strong> 1955, but also <strong>not</strong>e that <strong>not</strong> all dark areas in the<br />

southwest (bot<strong>to</strong>m right) part of the pho<strong>to</strong>graph are trees, as this areas was partially<br />

burnt grassland along the road. Compare <strong>to</strong> Figure 77. ........................................... 176<br />

Figure 79. Early-dry season fire scars during 2012 for the Oriners/Sef<strong>to</strong>n area, <strong>with</strong> all fires lit<br />

by humans in a coordinated ground and air based traditional fire regime program. Data<br />

are from the Northern Australia Fire Information (NAFI) website (www.firenorth.org.au).<br />

................................................................................................................................. 177<br />

Figure 80. Model of Oriners landscape interactions in the wet season ............................... 186<br />

Figure 81. Early dry season diagram ................................................................................. 187<br />

Figure 82. Road erosion leading in<strong>to</strong> Oriners Lagoon. ....................................................... 187<br />

Figure 83. Late dry season diagram ................................................................................... 188<br />

Figure 84. Early dry season diagram- Oriners Mob residence ............................................ 189<br />

Figure 85. Erosion channel upstream from Oriners Lagoon. .............................................. 190<br />

Figure 86. Model of fac<strong>to</strong>rs affecting water volume and s<strong>to</strong>rage capacity at Oriners Lagoon.<br />

................................................................................................................................. 191<br />

Figure 87. Jewfish Lagoon looking upstream. .................................................................... 192<br />

Figure 88. The recently widened and already eroding road crossing immediately upstream of<br />

Jewfish Lagoon. ........................................................................................................ 193<br />

Figure 89. The outlet sills and channels of Jewfish Lagoon looking downstream at a) the left<br />

outlet channel and b) the right outlet channel. ........................................................... 194<br />

Figure 90. Model of fac<strong>to</strong>rs affecting water volume and s<strong>to</strong>rage capacity at Jewfish Lagoon.<br />

................................................................................................................................. 194<br />

Figure 91. Mosqui<strong>to</strong> Lagoon looking upstream................................................................... 195<br />

Figure 92. Oblique air pho<strong>to</strong>s of Horseshoe Lagoon looking East. ..................................... 196<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

x

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

The project is the result of a research partnership <strong>be</strong>tween the Kowanyama people (through<br />

the Kowanyama Aboriginal Land and Natural Resource Management Office- KALNRMO)<br />

and the Water for a Healthy Country Flagship of the <strong>CSIRO</strong>. The authors wish <strong>to</strong><br />

acknowledge the assistance of all of the Indigenous 1 and non-Indigenous research<br />

participants in this study who made the field research possible – the Oriners Mob 2 , „Forest<br />

People‟ connected <strong>to</strong> the area, the Hughes family, and Indigenous cattlemen from other<br />

places who worked at Oriners over the years.<br />

Griffith University and the Australian Rivers Institute provided logistical support for scientific<br />

participation in this project. The work <strong>report</strong>ed here follows on from other work undertaken<br />

<strong>with</strong> the KALNRMO, including collaboration <strong>with</strong> research partners from the Tropical Rivers<br />

and Coastal Knowledge Research Hub (TRaCK - www.track.gov.au).<br />

<strong>CSIRO</strong> volunteers Chloe Gibbon, Mitchell Proudfoot and Roshini Vincent assisted <strong>with</strong><br />

interview transcripts and other research tasks. Finally, the authors thank Veronica Strang for<br />

generously providing her time and expertise as an expert reviewer. Her comments assisted<br />

the concluding phase of the <strong>report</strong>‟s production and provided fruitful suggestions for further<br />

analysis.<br />

Figure 1. Watercourse of Eight Mile Creek.<br />

1 This <strong>report</strong> follows <strong>CSIRO</strong> publication convention in using „Indigenous‟, but „Aboriginal‟ will <strong>be</strong> <strong>used</strong><br />

where it is part of an organisational name or formal quotation.<br />

2 The usage of „Oriners Mob‟ and „Forest People‟ as collective terms for Indigenous people associated<br />

<strong>with</strong> the Oriners area is explained further in 1.3 of the introduction.<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

xi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS<br />

ASTER – Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer<br />

BMP – Best Management Practice<br />

CYPAL – Cape York Peninsula Aboriginal Land<br />

CYPLUS – Cape York Peninsula Land Use Strategy<br />

<strong>CSIRO</strong> – Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization<br />

DERM – Department of Environment and Natural Resource Management<br />

DOGIT – Deed of Grant in Trust<br />

GPR – Ground Penetrating Radar<br />

KAC – Kowanyama Aboriginal Council<br />

KALNRMO – Kowanyama Aboriginal Land and Natural Resource Management Office<br />

LANDSAT – Land Satellite or Land Remote-Sensing Satellite<br />

LWD – Large Woody Debris<br />

LiDAR – Light Detection and Ranging<br />

MODIS – Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer<br />

NAFI – Northern Australia Fire Information<br />

NRM – Natural Resource Management<br />

OSL – Optical Stimulated Luminescence<br />

QPWS – Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service<br />

SRTM – Shuttle Radar Topography Mission<br />

TRaCK- Tropical Rivers and Coastal Knowledge<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

xii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<br />

This is a <strong>report</strong> about a local ecological knowledge re<strong>cover</strong>y, documentation and modelling<br />

project in south central Cape York, Queensland, Australia. It was funded through the Water<br />

for Healthy Country Flagship of the <strong>CSIRO</strong> under an agreement <strong>be</strong>tween the <strong>CSIRO</strong> and the<br />

Kowanyama Aboriginal Land and Natural Resource Management Office (KALNRMO). The<br />

geographical focus of the project is Oriners Station (Figure 2; Figure 3) but it also contains<br />

material relevant <strong>to</strong> Sef<strong>to</strong>n station and <strong>to</strong> other Indigenous lands north of the Alice River.<br />

Oriners is an area of the Cape that is associated <strong>with</strong> Olkol speaking peoples and contains<br />

some places of considerable cultural importance. In the wet season, Oriners country<br />

periodically floods and the soils <strong>be</strong>come saturated and boggy, but these characteristics have<br />

also meant that the area is relatively undeveloped, undistur<strong>be</strong>d, and of high ecological value.<br />

From the 1940s, the Oriners area was owned and <strong>used</strong> as a cattle station by several<br />

mem<strong>be</strong>rs of the non-Indigenous Hughes family, a well-known and longstanding pas<strong>to</strong>ral<br />

family in Northern Queensland, and many of the workers on the station during this period<br />

were local Indigenous people. In the early 1990s the property was purchased from the<br />

Hughes family by the Kowanyama Council and since that time, Oriners has <strong>be</strong>en<br />

intermittently occupied by a subset of Kowanyama people (sometimes called „the Oriners<br />

Mob‟) and managed for its conservation, natural resource management (NRM) and heritage<br />

value by the KALNRMO. The key community objective has <strong>be</strong>en <strong>to</strong> get people back on<strong>to</strong> the<br />

country and this <strong>report</strong> reflects the ongoing commitment of the KALNRMO and the wider<br />

Kowanyama community <strong>to</strong> building and maintaining a socially, economically and<br />

environmentally sustainable <strong>pre</strong>sence at Oriners. Indigenous people from around the region<br />

recognise the value and distinctive characteristics of the Oriners area and want <strong>to</strong> see it<br />

managed well. For them this project is one step in that ongoing process.<br />

The <strong>report</strong> also reflects the aspirations of the Water for a Healthy Country Flagship of the<br />

<strong>CSIRO</strong>, which committed significant funds <strong>to</strong> investigating and modelling indigenous<br />

hydrological knowledge and ecological understanding at key sites in Northern Australia. This<br />

was part of the ongoing commitment of the <strong>CSIRO</strong> <strong>to</strong> appropriate research partnerships <strong>with</strong><br />

Indigenous people, particularly in the area of knowledge documentation and natural resource<br />

management.<br />

The project <strong>report</strong> collates and synthesises some key aspects of knowledge about the<br />

Oriners area. It is divided in<strong>to</strong> 5 parts. Part 1 introduces some key framing concepts for the<br />

<strong>report</strong>. The first of these is „Working Knowledge‟, which is <strong>pre</strong>ferred here <strong>to</strong> more common<br />

la<strong>be</strong>ls like „Local‟, „Indigenous‟, and/or „scientific‟. Working Knowledge is <strong>used</strong> <strong>be</strong>cause it<br />

collectively descri<strong>be</strong>s the contexts in which much of the knowledge was gained (Indigenous,<br />

pas<strong>to</strong>ral, NRM, and scientific work), the provisional and ongoing quality of that knowledge,<br />

the fact that the men offering it come from a range of backgrounds (local, Indigenous, and/or<br />

scientific) and the fact that this <strong>report</strong> is oriented <strong>to</strong>wards ongoing NRM work in the area.<br />

Other key concepts are „Oriners Mob‟, which descri<strong>be</strong>s the contemporary Indigenous people<br />

most closely associated <strong>with</strong> the station, and „flooded forest country‟, which descri<strong>be</strong>s its two<br />

major distinctive characteristics from the perspective of its Kowanyama owners. Part 1 also<br />

reviews key literature related <strong>to</strong> the area, focusing on cultural, his<strong>to</strong>rical, and linguistic<br />

sources, descri<strong>be</strong>s the fieldwork methods (primarily semi-structured interviews) and the<br />

research participants. Finally it discusses the regional and strategic significance of Oriners as<br />

both a distinctive property and a key component of a growing num<strong>be</strong>r of properties in the<br />

area more heavily oriented <strong>to</strong> Indigenous and NRM objectives than <strong>to</strong> pas<strong>to</strong>ral activities.<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

xiii

Part 2 of the <strong>report</strong> contains a synthesis of key findings from the fieldwork interviews <strong>with</strong><br />

Indigenous cattlemen, senior men of the Hughes family, and long term KALNRMO Manager<br />

and co-author Viv Sinnamon. Interview material and analysis highlights:<br />

The distinctiveness of Oriners compared <strong>to</strong> areas further down in the Mitchell delta<br />

Weather patterns and water features of the area<br />

The animals most commonly observed there (both native and introduced)<br />

Human activities<br />

Key processes and relationships, including the role of water in animal movements,<br />

cattle mustering patterns, fire regimes and erosion processes.<br />

The remainder of part 2 <strong>not</strong>es some characteristics of „Working Knowledge‟ emerging from<br />

the material, highlights questions of classification and categorisation using Indigenous<br />

linguistic material from the literature, and discusses ideas of correlations and causes in local<br />

knowledge.<br />

Part 3 reviews key aspects of scientific knowledge of the Oriners landscape, focusing on<br />

physical conditions. Biological conditions are also considered, but in a more limited way due<br />

<strong>to</strong> data availability and researcher expertise. Since local data are limited, this synthesis is a<br />

work in progress and can <strong>be</strong> expanded upon in the future as additional scientific knowledge<br />

is collated or collected locally. Where available, local data and observations from the Oriners<br />

area are <strong>pre</strong>sented, but proxy data from other adjacent areas of the central Cape were<br />

reviewed where applicable. Most of the scientific information comes from past regional<br />

surveys by government programs and scientific researchers. Additional his<strong>to</strong>rical air<br />

pho<strong>to</strong>graphs and remote sensing data from satellites add value <strong>to</strong> these reconnaissance<br />

surveys and help set Oriners in a regional perspective. Data and observations on climate and<br />

rainfall, <strong>to</strong>pography and drainage, geology, soils, land systems, hydrology, hydrogeology,<br />

fluvial geomorphology, soil and gully erosion, vegetation, fire frequency, feral animals, and<br />

other native animals are reviewed. This collation of data and additions over time will <strong>be</strong><br />

useful for NRM and further scientific research for Oriners itself, as well as <strong>be</strong>ing of some use<br />

on adjacent stations. In this study, the emphasis is placed upon the relationships <strong>be</strong>tween<br />

scientific data and local observations.<br />

Part 4 attempts <strong>to</strong> synthesise and model important relationships and processes in the<br />

Oriners landscape based on the information in <strong>pre</strong>vious sections. Key foci are the seasonal<br />

hydrological regime, animal distributions, human activity, fire, and erosion. This part reflects<br />

the orientation of the original <strong>CSIRO</strong> funding source, which was aimed at documenting,<br />

systematising, and modelling Indigenous and/or local hydrological and ecological knowledge.<br />

It also reflects the practical and NRM-oriented focus of the overall project, rather than in the<br />

manner of an ethnobiological study, attempting <strong>to</strong> define, characterise and systematise<br />

worldviews or knowledge systems as a whole. The models focus on identifying critical<br />

physical and biological processes at work in the Oriners landscape <strong>with</strong> a view <strong>to</strong> identifying<br />

major areas for further research and/or management intervention. Within that overall frame,<br />

particular emphasis is given <strong>to</strong> understanding water and sediment flows in the permanent<br />

lagoon immediately adjacent <strong>to</strong> the station homestead, known as Oriners Lagoon (Od nodh<br />

in the local language). This is one of four major permanent lagoons on the station which have<br />

<strong>be</strong>en key sites for human hunting, pas<strong>to</strong>ral activity and residence in the past, and are likely <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>be</strong> key foci for management action in the years <strong>to</strong> come.<br />

Part 5 provides a short conclusion <strong>to</strong> the <strong>report</strong>, discussing the usefulness of the „Working<br />

Knowledge‟ framework, identifying key knowledge gaps for future research, and<br />

recommending next steps. An important next step emerges from a limitation of the current<br />

study, which in response <strong>to</strong> initial fieldwork circumstances, foc<strong>used</strong> on knowledge held by<br />

men (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous). This orientation deli<strong>be</strong>rately left considerable<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

xiv

space for a complementary study emphasising the (working) knowledge of women about the<br />

Oriners area. Part 5 also discusses the strategic value of Oriners in relation <strong>to</strong> the ongoing<br />

tenure and management developments in the central Cape. If those developments progress<br />

as planned, Oriners will lie at the centre of a substantial area of land <strong>be</strong>ing managed<br />

according <strong>to</strong> contemporary Indigenous and NRM objectives. These objectives may include<br />

pas<strong>to</strong>ral activity, but <strong>not</strong> give it the same priority it has had in the past. Therefore the<br />

theoretical approach and findings from the current study may have important implications for<br />

adjacent country and for Indigenous land management activity elsewhere in North<br />

Queensland.<br />

Parts 6-8 contain references, a glossary of scientific terms, and appendices containing the<br />

informed consent form, information about seasonal observations, and scientific lists of<br />

animals and plants recorded from the Oriners area.<br />

Figure 2. Mitchell River catchment <strong>with</strong> Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n Stations in the Alice River<br />

subcatchments.<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

xv

1 INTRODUCTION<br />

1.1 Working Knowledge<br />

Marcus Bar<strong>be</strong>r: When you say you are worried about the water, is there something in<br />

particular?<br />

Michael Ross: Just a general sense. Them big lagoons in the pho<strong>to</strong>. If it is <strong>not</strong> looked after.<br />

You look at the pigs ripping it <strong>to</strong> pieces and then you get human <strong>to</strong>urists leaving rubbish<br />

and you don‟t know what they are putting in the water. They could poison it. You don‟t need<br />

them sort of things happening. Pollution on them nice big lagoons. They <strong>be</strong>en there <strong>be</strong>fore<br />

our time and they all in good condition, bit of rough and tear around there, but you got <strong>to</strong><br />

look at the flow in the wet season, well in the wet season you can‟t move in Oriners. As far<br />

as I know you couldn‟t even move. Walk out <strong>to</strong> the back step, and in the horse paddock<br />

may<strong>be</strong>, then you bog, you are out of sight. That is boggy country. And you can‟t move very<br />

much. Back up a bit further, that is high country. Well, it‟s starting <strong>to</strong> get higher <strong>with</strong> them<br />

ridges, but <strong>not</strong> very much.<br />

This project foc<strong>used</strong> on documenting the recent ecological and hydrological his<strong>to</strong>ry of<br />

Oriners Station (Figure 3), as remem<strong>be</strong>red by cattlemen who worked on it in the past, and by<br />

those who are involved in its <strong>pre</strong>sent management. „Work‟ of different kinds has <strong>be</strong>en the<br />

basis for the majority of human <strong>pre</strong>sence in this sparsely inhabited area since the 1940s,<br />

although in more recent times the (often unwelcome) <strong>pre</strong>sence of non-Indigenous<br />

recreational hunters and fishers has grown in importance. The main title of this <strong>report</strong>,<br />

„Working Knowledge‟, refers <strong>to</strong> this labour his<strong>to</strong>ry but also <strong>to</strong> the fact that knowledge gained<br />

through activity is continually <strong>be</strong>ing negotiated and adapted, continually „worked out‟ in<br />

practice under changing conditions. The title also refers <strong>to</strong> how such knowledge is oriented <strong>to</strong><br />

particular purposes, namely <strong>to</strong> different kinds of economic activity- such knowledge is <strong>not</strong><br />

usually com<strong>pre</strong>hensive or encyclopaedic in the scientific sense, but functional and<br />

purposeful. It is knowledge useful for „getting things done‟. Many of men interviewed here<br />

were born and raised in the Kowanyama and Mitchell River area but <strong>not</strong> on Oriners itself,<br />

whilst others were cattlemen from elsewhere on the Cape who found themselves working on<br />

the station for a season, or a few months a year, or for a full year on a few occasions.<br />

Through repeated visits, these men formed a „working knowledge‟ of the Station, of its<br />

landscape features, its ecological and hydrological characteristics, of the processes of<br />

change going on <strong>with</strong>in it, and of the visible consequences of those changes. They also<br />

brought <strong>with</strong> them complementary and comparative knowledge gained from elsewhere in the<br />

Mitchell catchment and the broader Cape. This comparative knowledge enabled them both <strong>to</strong><br />

understand Oriners country more rapidly and <strong>to</strong> assess how it differed from other places in<br />

the broader North Queensland landscape.<br />

„Working Knowledge‟ was chosen as a title here <strong>be</strong>cause it also reflects a<strong>not</strong>her source of<br />

knowledge included in the <strong>report</strong>, knowledge coming from scientific work. Scientific research<br />

is work directed specifically at gaining knowledge of the natural world, and in this respect it<br />

differs from other forms of work which generate knowledge but do <strong>not</strong> have knowledge<br />

acquisition as their primary goal. However scientific research is rarely resourced and<br />

undertaken purely for the sake of extending the boundaries of knowledge in general. Rather<br />

it is directed <strong>to</strong>wards particular priorities and goals, as well as <strong>to</strong>wards achieving desired<br />

effects. Those influences shape the nature and conduct of the scientific work undertaken. In<br />

this project, the primary natural scientific knowledge about Oriners was generated and/or<br />

collated by one of the <strong>report</strong> authors, Jeff Shell<strong>be</strong>rg. Jeff has completed four years of<br />

hydrological and geomorphological research in the Mitchell River catchment, working <strong>to</strong><br />

complete his PhD on erosion processes in the catchment. This work is supported by his<br />

earlier career work as a hydrologist. Like the knowledge provided by the Indigenous<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

1

cattlemen and the Hughes family, the knowledge and expertise Jeff has provided has shaped<br />

the direction and orientation of the research effort.<br />

Figure 3. Cattle stations in lower Mitchell River catchment, <strong>with</strong> outlines of Kowanyama<br />

managed lands (red) including Oriners and Sef<strong>to</strong>n Stations. 3<br />

A third aspect of the „Working Knowledge‟ outlined here is that contemporary work and<br />

<strong>pre</strong>sence on Oriners Station is primarily based on NRM funding, resources, and priorities. An<br />

important participant in this project was Viv Sinnamon, who has lived at Kowanyama since<br />

1972, was heavily involved in the successful purchase of Oriners by the Kowanyama<br />

community by 1992 and, as the longstanding manager of the KALNRMO, is still involved in<br />

managing current NRM and heritage activity. Viv Sinnamon‟s perspective reflects his deep<br />

commitments <strong>to</strong> Kowanyama and its people, but also commitments <strong>to</strong> Indigenous<br />

management, NRM and cultural landscape management as important forms of work, both in<br />

terms of maintaining ecologically valuable landscapes and in promoting sustainable<br />

Indigenous livelihoods in remote areas. Contemporary NRM is an increasingly important<br />

component of Indigenous peoples‟ relationships <strong>with</strong> their country, particularly in terms of<br />

providing support for ongoing <strong>pre</strong>sence and economic activity in regional and remote areas.<br />

It provides people <strong>with</strong> the resources and opportunities <strong>to</strong> visit and care for places that matter<br />

<strong>to</strong> them, but importantly for this study, it also influences their engagements <strong>with</strong> the country.<br />

It affects the timing of the visits people make, the activities they undertake whilst they are<br />

there, and the particular aspects of the country they are encouraged <strong>to</strong> focus their attention<br />

on. The „working knowledge‟ of the <strong>pre</strong>sent day derives from past ways of living and working<br />

on Oriners, particularly those of the cattle station era, but it is also shaped by the newer<br />

requirements and priorities emerging from NRM and conservation. The orientation of this<br />

<strong>report</strong> and the categories <strong>used</strong> <strong>with</strong>in it reflect the priorities of this contemporary work. In this<br />

sense it <strong>to</strong>o is a „working document‟, both provisional and work-oriented in nature.<br />

3 As discussed in more detail <strong>be</strong>low, transitions in tenure will lead <strong>to</strong> greater Indigenous management<br />

involvement in adjacent stations - Crosbie, Wulpan, and Dixie Stations (among others) in partnership<br />

<strong>with</strong> the Queensland Government.<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

2

Identifying three different forms of relevant work does <strong>not</strong> mean that those categories are<br />

discrete and separate. Firstly, although there are differences, the nature of the work and its<br />

associated knowledge overlap: a successful cattleman needs <strong>to</strong> understand and act on<br />

information <strong>with</strong> scientific origins, as well as undertake land management action that accords<br />

<strong>with</strong> NRM principles; a scientist may <strong>be</strong> motivated by conservation objectives, and need <strong>to</strong><br />

understand how cattle num<strong>be</strong>rs and movements impact on the main object of his or her<br />

study; the contemporary Indigenous natural resource manager may engage <strong>with</strong> scientists<br />

and scientific knowledge on a regular basis as part of normal work duties, as well as relying<br />

on the ongoing <strong>pre</strong>sence of healthy cattle <strong>to</strong> supplement meat supplies. It is <strong>not</strong> just the<br />

nature of work and knowledge that overlap, people do <strong>to</strong>o. A num<strong>be</strong>r of elders and senior<br />

land managers in the Oriners Mob are former cattle workers, some <strong>with</strong> decades of<br />

experience in the industry. Now their focus is on NRM projects and activities, but the skills<br />

and perspectives they bring <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong>ar on those projects reflect that past his<strong>to</strong>ry of a different<br />

but related kind of work. Contemporary Indigenous leaders and managers of Kowanyama<br />

and Oriners seek a similar „decision support system‟ that allows them <strong>to</strong> combine both<br />

Indigenous and western sciences that in addition allows the reoccupation of country by its<br />

people. This stance is reflected in the recently produced Terms of Reference for the<br />

Kowanyama Wetland Advisory Group (KALNRMO 2010). 4 It is important <strong>to</strong> identify the<br />

different sources of knowledge, information and associated experience coming from the<br />

research participants, but also the overlaps and commonalities <strong>be</strong>tween them.<br />

There is one further way in which the emphasis on „working knowledge‟ should <strong>not</strong> <strong>be</strong><br />

misunders<strong>to</strong>od. Work is a part of life, <strong>not</strong> the whole of life, and Oriners is remote and<br />

inaccessible, so working at Oriners has usually involved living there, if sometimes only for<br />

short periods. People gain crucial knowledge and learn important lessons in non-work<br />

situations; in casual conversations at mealtimes, whilst fishing for pleasure, during periods of<br />

rest and reflection, and so on. Furthermore, allowing people <strong>to</strong> learn by observing, by <strong>be</strong>ing<br />

part of the scene rather than an active participant, is a crucial aspect of Indigenous modes of<br />

teaching, particularly of teaching children (Hamil<strong>to</strong>n 1981). This occurred regularly during the<br />

early establishment of a contemporary base at Oriners, when younger people spent<br />

considerable time having long conversations <strong>with</strong> knowledgeable Indigenous elders from the<br />

area. Contact <strong>with</strong> an experienced long-term non-Indigenous pas<strong>to</strong>ralist (now deceased) was<br />

also important during this time. A num<strong>be</strong>r of currently active mem<strong>be</strong>rs of the Oriners Mob<br />

owe their knowledge <strong>to</strong> those times spent <strong>with</strong> old men and women now gone. Residence<br />

over several wet seasons spent at Oriners isolated from Kowanyama from Oc<strong>to</strong><strong>be</strong>r through<br />

<strong>to</strong> May provided a small num<strong>be</strong>r of the Oriners Mob <strong>with</strong> an opportunity <strong>to</strong> get <strong>to</strong> know the<br />

country intimately. Rather than limiting knowledge <strong>to</strong> just that gained during work, what<br />

„working knowledge‟ emphasises here is the particular role that organised work played in<br />

peoples‟ collective and individual <strong>pre</strong>sence at Oriners (particularly men), as well as the<br />

practical, provisional, and work-oriented nature of the knowledge recorded for this project. 5<br />

4 The terms <strong>not</strong>e that:<br />

“Traditional Owner knowledge of country is integral <strong>to</strong> the operations of the Kowanyama land<br />

management agency and would <strong>be</strong> incorporated <strong>with</strong> contemporary western science <strong>to</strong> develop <strong>be</strong>st<br />

practice aboriginal management plans. The Terms of Reference for the TAG have <strong>be</strong>en developed<br />

<strong>with</strong> this in mind, and <strong>with</strong> understanding of the need for flexibility in response <strong>to</strong> evolution/change in<br />

circumstances, capacity, wetland management issues, stakeholders and TAG mem<strong>be</strong>rship.”<br />

(KALNRMO 2010:3)<br />

5 It is also worth <strong>not</strong>ing two further bases for selecting the term <strong>to</strong> descri<strong>be</strong> the work here. Firstly,<br />

„Working Knowledge‟ avoids potential pitfall <strong>with</strong>in an Indigenous domain in which some research<br />

participants have deep traditional ties going back generations <strong>to</strong> the area in question, whilst others are<br />

speaking based on working there for a year or two <strong>be</strong>fore moving on. Whilst „Working Knowledge‟<br />

significantly constrains the full spectrum of knowledge held by the former, it also clearly (and<br />

appropriately) identifies the perspective of the latter. Secondly, „Working Knowledge‟ was an<br />

appropriate focus for a primary researcher (Bar<strong>be</strong>r) who was new <strong>to</strong> the Kowanyama community and<br />

the area and was undertaking a project <strong>with</strong> constrained field time. Detailed questions about more<br />

culturally sensitive <strong>to</strong>pics, which had also already <strong>be</strong>en documented by others (Strang 2001), would<br />

<strong>be</strong> unlikely <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> well received.<br />

Working Knowledge at Oriners Station, Cape York<br />

3

As a contrast and complement, it is useful <strong>to</strong> <strong>not</strong>e two other accounts from this area that<br />

emphasise different aspects of Indigenous peoples‟ knowledge of Oriners country. Strang<br />

(2001) <strong>report</strong>s on an extensive cultural mapping exercise <strong>to</strong> record what is still remem<strong>be</strong>red<br />

about the important Dreaming or Ancestral s<strong>to</strong>ries of places in the area <strong>be</strong>tween the Alice-<br />

Mitchell area and Oriners. Her account emphasises and reflects the spiritual and<br />

mythological importance of the landscape <strong>to</strong> local people, as well as its articulation <strong>with</strong> local<br />

his<strong>to</strong>ries of use. From 1996-1997 Stewart and Hamil<strong>to</strong>n produced a detailed ethnobotany<br />

from the Oriners area, bringing Indigenous elders <strong>to</strong>gether <strong>with</strong> non-Indigenous researchers<br />

<strong>to</strong> record detailed knowledge about plants, including their traditional uses. This current <strong>report</strong><br />

complements those two accounts, as it focuses on broader landscape processes, his<strong>to</strong>rical<br />

ecology, and personal and regional his<strong>to</strong>ry. Crucially, it also involves interviews <strong>with</strong><br />

mem<strong>be</strong>rs of the non-Indigenous Hughes family, who owned and operated the station for<br />

several decades. For intellectual property and community reasons, both Strang and Stewart<br />

and Hamil<strong>to</strong>n‟s <strong>report</strong>s remain s<strong>to</strong>red in the restricted archives of the KALNRMO, although<br />

some information contained in the latter <strong>report</strong> is available by investigating botanical entries<br />

in the online Olkol dictionary subsequently produced by Hamil<strong>to</strong>n. The current document is<br />

public and <strong>to</strong> <strong>be</strong> shared <strong>with</strong> both Indigenous and non-Indigenous research participants as<br />

well as <strong>be</strong>ing available through the <strong>CSIRO</strong> <strong>to</strong> the wider Australian community. This affects its<br />

content and scope, as well as the degree <strong>to</strong> which it references detailed content from the<br />

earlier <strong>report</strong>s, <strong>not</strong>ably restricted cultural matters and information on plant uses. What the<br />

existence of those <strong>report</strong>s usefully demonstrates here is that knowledge is multifaceted, and<br />

knowledge documentation can have a range of orientations.<br />

The above paragraphs refine and clarify why the term „Working Knowledge‟ is <strong>used</strong> here as<br />

an orientation. It is appropriate in describing:<br />

the particular assemblage of research participants;<br />

the kinds of knowledge recorded;<br />

the provisional and purposeful orientation of that knowledge;<br />

the categories under which that knowledge is organised in the <strong>report</strong>;<br />

and the contexts and applications for which the <strong>report</strong> might <strong>be</strong> <strong>used</strong> in the future.<br />

1.2 Flooded forest country at Oriners Station<br />

As the title suggests, alongside „working knowledge‟, a second key aspect of Oriners Station<br />