The techniques of carpentry used to make the Torrijos ceiling are also found in ceilings far beyond Iberia’s shores in colonial South America, where they were brought by craftsmen who combined carpintería de lo blanco (‘white carpentry’) with materials and practices found locally.

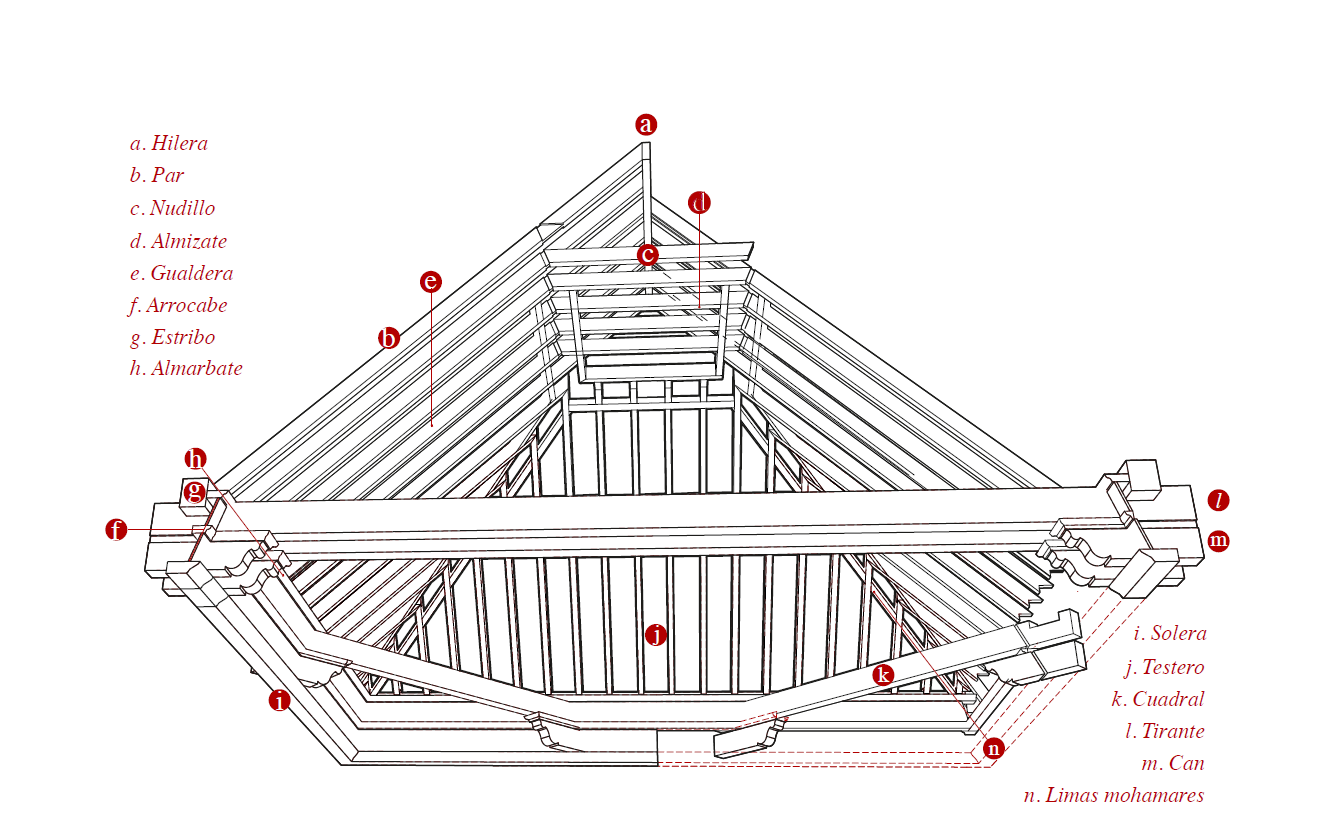

During the 16th century, the expansion of the Spanish crown in South America led to the establishment of the Viceroyalty of Peru, a political-administrative entity with Lima as its capital (since 1542). The viceroyalty encompassed almost all South America, excluding present-day Venezuela and Brazil. These territories, which were extremely diverse both ethnically and environmentally, underwent a process of urbanisation during the first century of Spanish rule. This was characterised by the extensive construction of residential buildings, churches, and governmental palaces. Initially, the earliest constructions were temporary in nature. However, the imperative for evangelisation and territorial control drove the imposition of Spanish construction practices throughout the viceroyalty. Consequently, the par-nudillo system, comprising the principal and collar beam, became the preferred method for constructing wooden timber frames for carpentry ceilings.

The par-nudillo system was used in structures with wooden roofs, especially in religious architecture, of various types. This trend was observed in the kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula – especially Castile – as well as in the Viceroyalty of Peru. The link between the Peruvian and Spanish timber frames extended beyond typology: it formed part of the approach to construction implemented by the Crown of Castile in the conquered territories from the 15th century onwards. These territories encompassed the Canary Islands, the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, and Spanish America. Broadly speaking, this approach to construction, which could be considered a form of colonial imposition, focused on the construction of churches, or the conversion of non-Christian structures into churches, as a means of evangelising and controlling the local population. These churches shared common features, including an altar, a nave, and a triumphal arch separating the two spaces. Different construction typologies were employed in each space, with wood being prominently employed for the roof. The replication of this church model contributed to the spread of Spanish carpentry and its application in colonial contexts during the early modern period.

The arrival of carpenters from various regions of the Iberian Peninsula from the 16th to the first half of the 17th century facilitated the introduction and local development of carpentry techniques in the viceroyalty, considering the use of local materials and the frequent seismic activity. Their role within the colonial context was crucial, as they served as agents for the transmission of technical knowledge. This can be observed in the numerous construction contracts that involved these Iberian carpenters as master builders. Furthermore, these same carpenters trained Indigenous peoples, Africans, and individuals of mixed heritage through apprenticeship contracts (asiento), who later became invaluable assistants to these Iberian master carpenters.

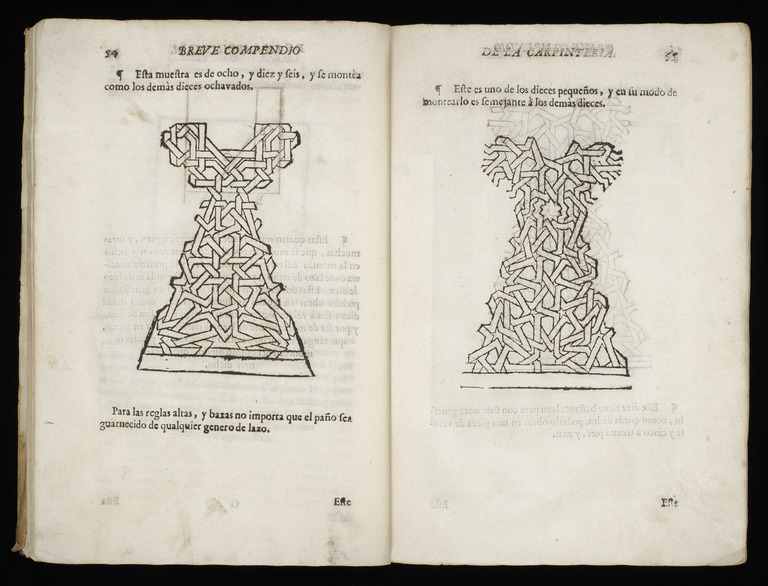

Although famous treatises were written on the transmission of carpentry techniques in the Hispanic world in the 17th century, they do not shed light on its development in the Viceroyalty of Peru. The renowned treatise by Diego López de Arenas (Seville, 1633) arrived late in Lima, during the second half of the 17th century – a time when ceiling construction was already declining in the viceroyalty. It was discovered in the libraries of Manuel de Escobar (1640 – 1695) and Santiago de Rosales (1681 – 1759), esteemed master builders of the city. No other copy has been found elsewhere in the viceroyalty thus far, and there is no mention of it in any library or testamentary inventory.

The treatise written by Fray Andrés de San Miguel (Mexico, about 1630) was never published, and there is no evidence of its circulation during the 17th century. It wasn’t until the 20th century, specifically in 1969, that it was published by the Mexican art historian Eduardo Baez. This implies that the knowledge passed down by Iberian carpenters originated primarily from their own practical experience in the workshop. In fact, the vast number of ceilings constructed during the latter half of the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century can only be attributed to the exceptional technical expertise of the carpenters, rather than the availability of treatises, which seem to have played a minor role in their training.

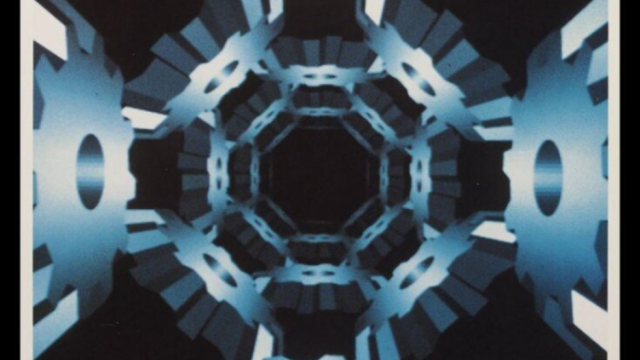

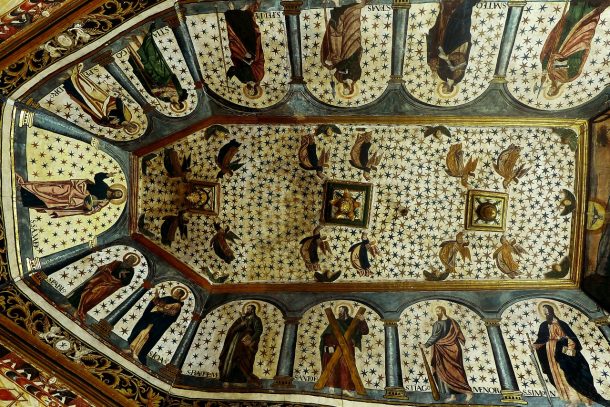

The Viceroyalty of Peru served as a centre for the technical advancement of carpentry. The most prominent cities in the Spanish Andes, including Santafé de Bogotá, Tunja, Cartagena de Indias (Colombia), Quito (Ecuador), Lima and Cusco (Peru), La Plata and Potosí (Bolivia), coincided with the locations where new building solutions emerged. This development was facilitated by the influence of the Church, religious orders, and local elites, who promoted the construction of larger churches, often featuring three naves and wooden roofs. Notably, these cities witnessed the use of lacería (interlaced geometric decoration) as a decorative element in wooden timber frames. Even in the 17th century, lacería domes were constructed, such as the one covering the main staircase of the Convent of San Francisco in Lima (shown above).

Geometric interlacing stands out as one of the most prominent forms of ornamentation in the carpentry of the Viceroyalty of Peru. From the late 16th century until around 1650, over 70 par-nudillo timber frames adorned with ornamental lacería were created in the viceroyalty.

Most of these examples were concentrated in Lima. However, today, many of them have disappeared due to earthquakes and changes in construction practices from the second half of the 17th century onwards:

In their most basic form, the wooden timber frames had no ornamental lacería, and the beams were not painted. This type can be seen in several churches, often distinguished by the squared timbers, some of which had un-squared beams directly obtained from trees:

In the Andean regions of the Viceroyalty of Peru, there existed an ancient construction culture that developed various methods for constructing timber frames. In most cases, these frames were created using a structure of wooden beams arranged in a tripod formation, secured at the ends with llama hides (tientos). A thin layer of mud was applied over this structure to provide insulation, followed by a layer of straw to protect against wind and rain. This technique, known as the Andean tijerales, underwent a process of hybridisation with the Spanish par-nudillo system during the colonial period. These hybrid techniques emerged in areas distant from the centres of colonial power, while the use of forms closer to Iberian construction models was predominant in these centres. It is highly probable that this geographical distance facilitated the preservation of local construction techniques, as evidenced in certain regions of Charcas (present-day Bolivia). Documentation from the 17th and 18th centuries indicates that despite the presence of travelling carpenters, it was the local community that actively participated in the construction process and subsequent maintenance of the churches.

Several examples of these can be found in churches along the route connecting Huancavelica (Peru), Potosí (Bolivia), and Arica (Chile) for the export of silver during Spanish rule. In Bolivia, this typology is seen in the chapel of Salinas de Garci and Quillacas; in Chile, in the church of Parinacota; and in northern Argentina, in the church of Yavi. These hybrid timber frames were the result of the negotiation between local and Spanish construction techniques, which is evident not only in the use of local wood but also in the utilisation of llama hide (tientos) to tie the beams, replacing the use of joints to assemble the wooden pieces characteristic of Spanish carpentry.

In the Andean region of the Viceroyalty (Peru, Bolivia, northern Chile, and Argentina), various types of wood were employed, including alder (Alnus jorullensis), tajibo or guayacán (Tabebuia chrysantha), cedar (Cedrela odorata), queñua (Polylepis tomentella), among others. In Lima, where there was a limited forested area, the importation of wood played a crucial role in the advancement of carpentry. This included pine (Pinus oocarpa, Pinus maximinoi, Pinus tecunumanii) from Nicaragua, oak (Tabebuia rosea) from Guayaquil (Ecuador), alerce or cypress (Fitzroya cupressoides) from Chilean Patagonia, and cocobolo (Dalbergia retusa) from Guatemala. Additionally, the cardon (Trichocereus atacamensis), a cactus native to northern Chile, northwestern Argentina, and southern Bolivia, was also used.

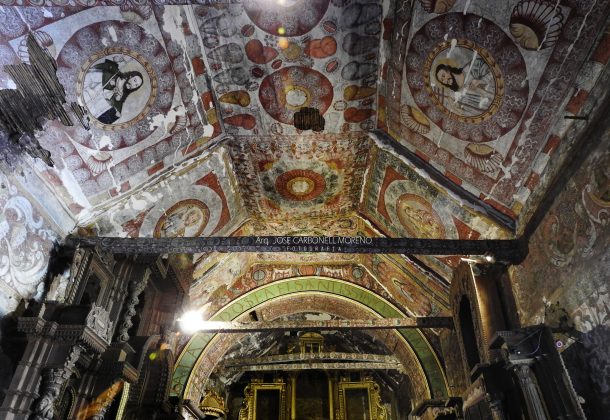

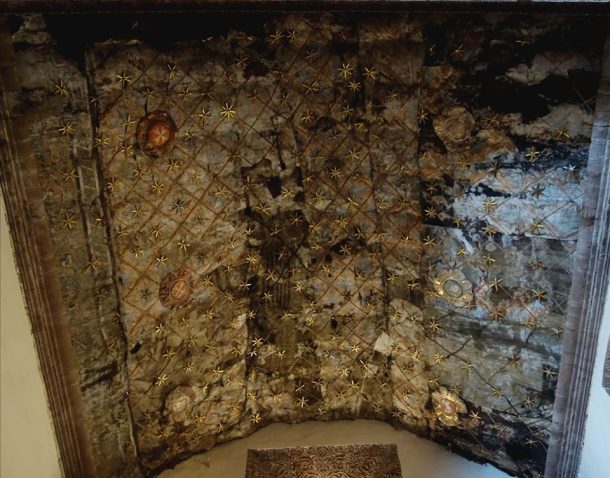

Hidden timber frames were another method used to cover Andean viceregal churches. This decorative technique involved covering the wooden structure with planks, textiles, or a layer of mud. In the case of mud ceilings, a layer of mud composed of plant fibres, human or animal hair, and a plant-based binder was applied. On top of this, a layer of lime was applied which, once dry, became the ground for a pictorial programme, characterised by the use of Christian iconography, floral and plant motifs, and the representation of textiles.

Examples of this decorative typology can be found in the churches of the southern valley of Cusco (Peru), such as Marcapata, Checacupe, Cacha, or Canincunca. Other types of hidden timber frames, covered with planks or textiles, appear in Tunja (Colombia), Juli (Peru), or Curaguara de Carangas (Bolivia).

Although many of the construction and ornamental typologies mentioned appear in other territories of the Spanish Crown, there is no doubt that in the Andean region, the ceilings reveal forms and techniques that originated from local processes of constructive negotiation. This gave rise to what I call “technical divergence”, in which Spanish construction methods in carpentry were developed using local materials and local aesthetic decisions, and in which Andean construction culture incorporated Spanish carpentry techniques.

This technical divergence arose through the transmission of the construction culture of Spanish carpenters. Alongside these Spanish carpenters, there were individuals of different races and ethnicities who participated in the apprenticeship process and the practice of carpentry. Their race and ethnicity are known through the contracts in which they are documented. Among the Indigenous people, notable individuals include José de la Cruz and Francisco Morocho, who were involved in the construction of the church of San Francisco in Quito. Martin Taguada contributed to the ceiling of San Roque in Quito, while Lucas Quispe played a key role in the woodwork of the convent of Santo Domingo in Cusco. Among the Africans, Francisco de Viruéz stands out as one of the builders of the church of Bosa in present-day Colombia. Another significant figure is Luis de Lagama, renowned as a skilled carpenter and mason in Lima towards the end of the 16th century. It is challenging to verify whether there were declared Moriscos among these carpenters, due to a royal decree of 1543 which ordered their expulsion from the American territories and prohibited their travel from the Iberian Peninsula.

Thus, Indigenous peoples, Africans (transatlantic slaves and libertos or freedmen, and their descendants) and individuals of mixed heritage were decisive actors in defining Andean carpentry in colonial contexts, and are the overlooked builders of an architectural heritage that must continue to be investigated.