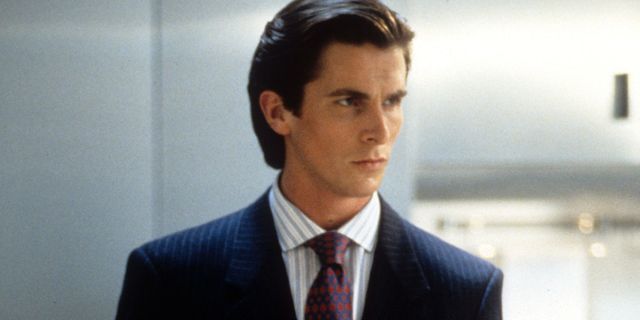

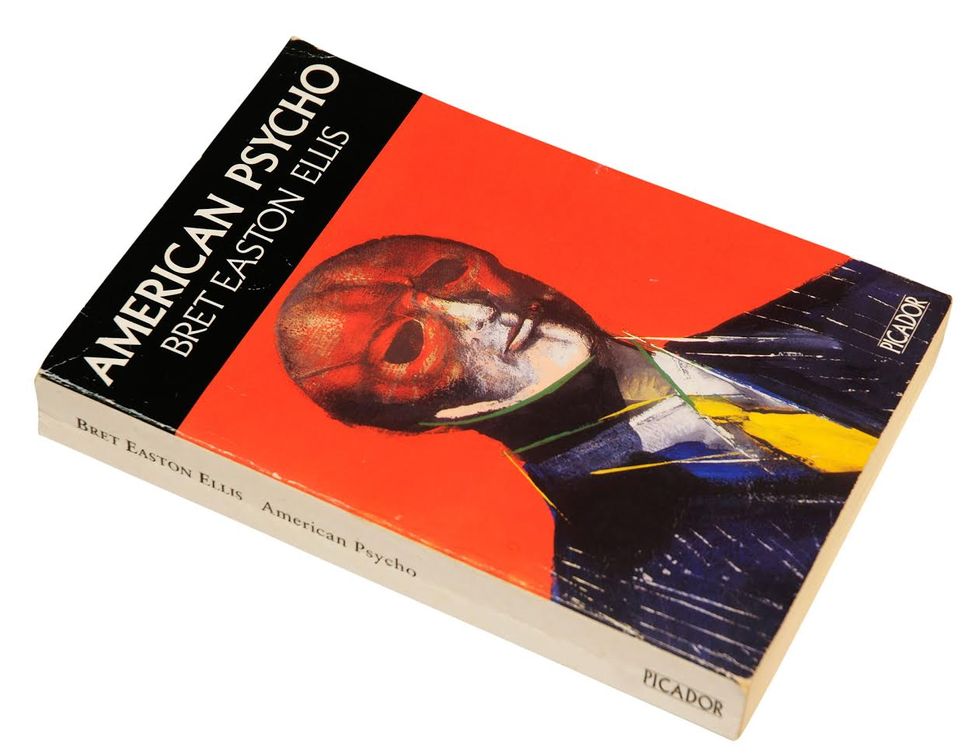

After 25 years I'm occasionally and increasingly asked by readers of a book I published in 1991 called American Psycho (later made into a movie in 2000) about where its narrator, Patrick Bateman, would be now. This question has become even more prevalent lately, on the book's 25th anniversary, either at appearances and signings or on social media, usually while fans share this year's Halloween costume pic—almost always the blood-splattered sheer slicker that Christian Bale's Bateman wears in the film as he kills supposed Pierce & Pierce rival Paul Allen (Jared Leto) with an ax to the head.

In particular they wonder where the Wall Street yuppie and serial killer, haunting the late '80s streets and nightclubs and restaurants of Manhattan, would be residing if he were recreated and resituated in 2016.

If you read the book carefully and have a sense of Manhattan geography, you know that Bateman's sleek and minimalist Upper West Side apartment has an imaginary address. This suggests that Bateman might not be a completely reliable narrator, that perhaps he's a ghost, an idea, a summing up of the values of that particular decade filtered through my '80s literary sensibility: moneyed, beautifully attired, impossibly groomed and handsome, morally bankrupt, totally isolated and filled with rage, a gorgeously dressed and empty thing, a young and directionless mannequin hoping that someone, anyone, will save him from himself.

All of this happens during the end years of the Reagan '80s.

So what would I tell fans who ask me where Patrick Bateman would be now, as if he were actually alive, tactile, wandering through our world in flesh and blood? For a while during the mid- to late '90s—at the height of the dotcom bubble, when Manhattan seemed even more absurdly decadent than it did in 1987, before Black Monday—it was a possibility that Bateman, if the book had been moved up a decade, would have been the founder of a number of dotcoms.

He would have partied in Tribeca and the Hamptons, indistinguishable from the young and handsome boy wonders who were populating the scene then, with their millions of nonexistent dollars, dancing unknowingly on the edge of an implosion that happened mercilessly, wiping out the playing field, correcting scores. While twirling through that decade myself as a youngish man, I often thought that this was a time Bateman could have also thrived in, especially with the advent of new technologies that could have aided him in his ghoulish obsession with murder, execution, and torture—and in ways to record them.

And sometimes I think that if I had written the book in the past decade, perhaps Bateman would have been working in Silicon Valley, living in Cupertino with excursions into San Francisco or down to Big Sur to the Post Ranch Inn and palling around with Zuckerberg and dining at the French Laundry, or lunching with Reed Hastings at Manresa in Los Gatos, wearing a Yeezy hoodie and teasing girls on Tinder. Certainly he could also just as easily be a hedge-funder in New York: Patrick Bateman begets Bill Ackman and Daniel Loeb.

There was a shoddy, barely released sequel made a few years after the Mary Harron–directed American Psycho opened theatrically, but it had little to do with Patrick Bateman (he's killed off in the first five minutes), and there has been talk of a remake of Harron's original, as well as TV series developed at various networks either continuing the Bateman saga or updating it to the present day. There are Patrick Bateman action figures sold online, and there is nowAmerican Psycho: The Musical, which after a sold-out London run transfers to Broadway at the end of March.

(Full disclosure: I've heard demos of the score and read the book of the musical but have yet to see the finished product. The idea seemed farcical at first—though I was reminded that such musicals as Sweeney Todd and Carrie certainly brought the carnage—but in the end I was convinced by the vision of the creative team.)

All of these things have sometimes distracted me, not only about Bateman now versus Bateman then but also about how the character was created and how strange it is to see the embodiment of my youthful pain and angst morph into a metaphor for the disruptive greed of a decade, as well as a continuing metaphor for anyone who works on Wall Street—a symbol of corruption, in fact—or for anyone whose perfect façade masks a wilder, dirtier side, as in: "My boyfriend's such a Patrick Bateman."

As the writer of American Psycho I have no idea—and I can take no responsibility for—why it has such resonance, though it might be that the moment we're living in now is, if anything, even more ripe for the metaphor of a serial killer.

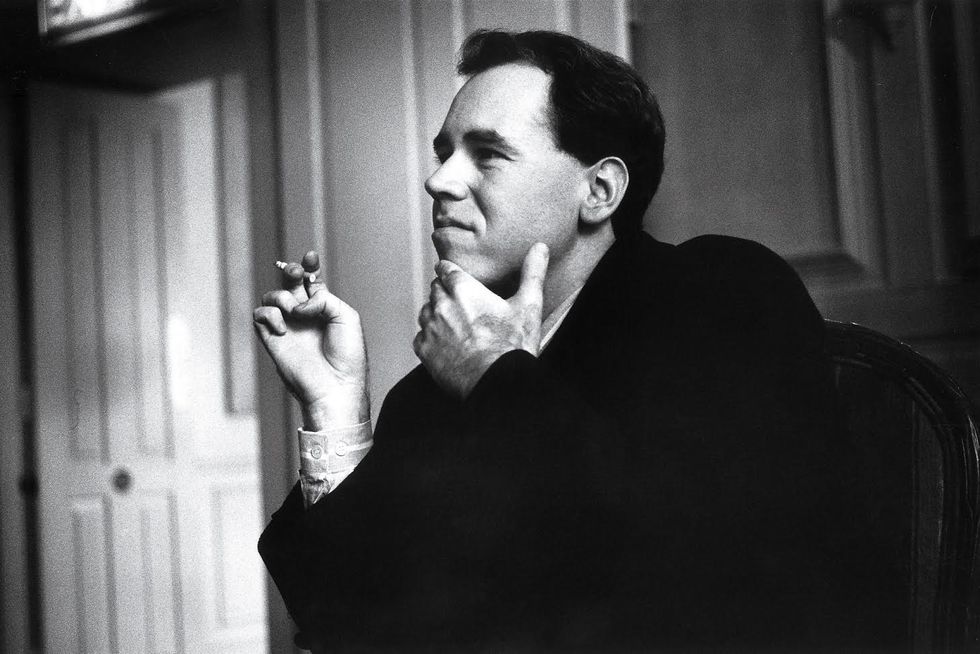

Part of why it's hard to reimagine Bateman anywhere else and at any other time is because of where I was during the years I was writing about him, both emotionally and physically. I find it stranger as I get older that one of the most archetypal characters in recent American fiction—someone who was to me a faceless and free-floating representation of yuppie despair—was actually a character based on my own anger and frustration set in a very specific place and time.

Moving to Manhattan after graduating from college with a BA—that phrase alone seems embalmed in a distant era, such an antiquated pipe dream in our new economy, where debt-saddled kids can't afford to move to Manhattan after graduating from college—I found myself in a city that had swallowed the values of the Reagan '80s as a kind of hope, an aspiration, something to rise toward.

And even though I disagreed with the ideology being embraced in 1987, I was still twirling through that time trying, as Bateman says, to fit in to some degree. I might have been disgusted with the values then and what it meant to be a man—a successful man—but where else was I going to go? (True, I had already published two novels, but they had nothing to do with the emptiness, the void, I was feeling.) Wasn't the whole point of becoming an adult learning how to navigate, to process, to compromise one's youthful dreams and be fine with wherever you end up?

The rage I felt over what was being extolled as success, what was expected from me and all male members of Gen X—millions of dollars and six-pack abs—I poured into the fictional creation of Patrick Bateman, who in many ways was the worst fantasy of myself, the nightmare me, someone I loathed but also found in his helpless floundering sympathetic as often as not. And he was completely correct in his criticism of the society he was a part of.

American Psycho was about what it meant to be a person in a society you disagreed with and what happens when you attempt to accept its values and live with them even if you know they're wrong. Well, insanity creeps in and overwhelms; delusion and anxiety are the focal points.

In other words, this is the outcome of chasing the American dream. Isolation, alienation, the consumerist void increasingly in thrall to technology, corporate corruption—all the themes of the book still hold sway three decades later. We are in a time when the one percent are richer than any human has been before, an era when a jet is the new car and million-dollar rents are the reality. New York today is American Psycho on steroids.

And despite the idea of interconnectivity via the internet and social media, many people feel more isolated than ever, increasingly aware that the idea of interconnectivity is an illusion. Especially when you're sitting by yourself in a room staring at a glowing screen while having access to the intimacies of countless other lives, which is an idea that mirrors Patrick Bateman's loneliness and alienation, everything is available to him and yet an insatiable emptiness remains.

This mirrored my own feelings during those years in the apartment on East 13th Street I was living in as the '80s came to an end.

In the period when the novel takes place Bateman is a member of the as yet unnamed one percent, and he would probably still be now. But would Patrick Bateman actually be living somewhere else, and would his interests be any different? Would better criminology forensics (not to mention Big Brother cameras on virtually every corner) allow him to get away with the murders he tells the reader he committed, or would his need to express his rage take other forms?

For example, would he be using social media—as a troll using fake avatars? Would he have a Twitter account bragging about his accomplishments? Would he be using Instagram, showcasing his wealth, his abs, his potential victims? Possibly. There was the possibility to hide during Patrick's '80s reign that there simply isn't now; we live in a fully exhibitionistic culture.

Because he wasn't a character to me as much as an emblem, an idea, I would probably approach him the same way now and address his greatest fear: Would anyone be paying any attention to him? One of the things that upsets Patrick is that, because of a kind of corporate lifestyle conformity, no one can really tell the other people apart (and what difference does it make, the novel asks).

People are so lost in their narcissism that they are unable to distinguish one individual from another (this is why Patrick gets away with his crimes), which ties into how few things have really changed in American life since the late '80s; they've just become more exaggerated and accepted. The idea of Patrick's obsession with himself, with his likes and dislikes and his detailing—curating—everything he owns, wears, eats, and watches, has certainly reached a new apotheosis. In many ways the text of American Psycho is one man's ultimate series of selfies.

Christian Bale changed the look of Bateman, giving my construct a face, a (spectacular) body, and a confused voice, creating his own iconic portrayal, which is what happens when you make a movie from a well-known text, whether it's Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O'Hara or James Mason as Humbert Humbert or Jack Nicholson as Jack Torrance. These actors get stuck in our heads, and we can never read the book again without imagining them inhabiting that character—and they stay stuck in time.

But readers first came across Patrick Bateman near the end of my second novel, The Rules of Attraction. He appears late one night in a Manhattan hospital in the waning days of 1985 waiting for his father to die while his younger brother Sean (one of the novel's narrators) begrudgingly visits—supposedly to pay his last respects but really because he needs money; Sean ends up getting dissed by the older brother he loathes.

So Patrick Bateman began to become real for me years before I started American Psycho, but I didn't know it—which is why at times I find the question of where Patrick Bateman might be now so elusive. He's so fixed for me in that particular time and place that I simply can't imagine him anywhere but in that lonely office at Pierce & Pierce, committing his unfathomable crimes in that imaginary apartment on the Upper West Side.

Like many characters a writer creates, Patrick Bateman lives on without me, regardless of how I felt or how close we became during the years it took me to write about him. Characters are often like children leaving the nest, going out into the uncaring world and being either accepted or not accepted, ignored or extolled, criticized or prized, no matter how the writer might feel about them.

I check in with Patrick every now and then—as with this article you're reading—but he has been living his own life for some time now, and I rarely feel as if I have guardianship over him, or any right to tell him where he would or would not be today, decades after his birth.

This story originally appeared in the March 2016 issue of Town & Country.