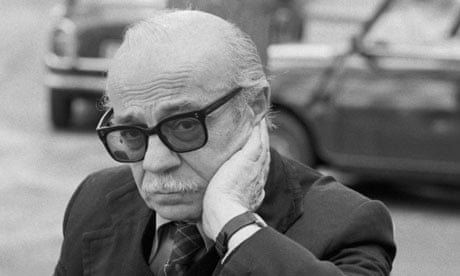

Ernesto Sábato, who has died aged 99, was the last of a generation of Argentinian writers whose moral rectitude in the midst of political chaos gave them an importance far beyond whatever audience their fictional books attracted. His first novel, El Túnel (The Tunnel, 1947), won him a respectful following, but it was his two later novels, Sobre Héroes y Tumbas (On Heroes and Tombs, 1961) and Abaddón el Exterminador (The Angel of Darkness), that earned him his reputation. In these books, Sábato explored the themes of isolation and the lack of communication between individuals who are caught up in a succession of events they can do nothing to control, and are hard put to understand. He likened all of us to blind people stumbling in the darkness.

Sábato was born into a well-to-do family in Rojas, Buenos Aires province. As a youth, he became involved in the effervescent intellectual atmosphere of the Argentinian capital as it grew vertiginously and entered the modern world. Among the new ideas the thousands of European immigrants brought to Argentina was an enthusiasm for the communist revolution in Russia. Sábato first came into contact with this radicalism when he began to study science at the university town of La Plata, near the capital.

La Plata was also a centre for the meat-exporting industry, and Sábato's desire for social change was fuelled by the workers' conditions: "These were the largest meat-packing plants in Argentina, where all kinds of immigrants were mercilessly exploited. They lived in tin shacks, surrounded by huge puddles of stinking water."

The first of many military interventions in 20th-century Argentina took place in 1930. Sábato's response, in 1933, was to become the secretary of the Communist Youth Federation in Argentina. However, Sábato said he was soon troubled by the news of persecution coming from Russia. When he was chosen to go to Moscow to receive more indoctrination, he escaped during a stopover in Brussels, and went to live in Paris, where he stayed for several months for fear of reprisals from his former comrades.

By 1935 he was back in Argentina, and completing his studies in physics and mathematics. Such was his ability in these fields that he was offered a grant to return to Europe, to undertake research at the Curie Institute, in Paris. By now he had married his childhood sweetheart, Matilde Kusminsky-Richter.

In Paris, he had a spiritual and vocational crisis. He decided he could no longer devote himself to science, and what he really had to do was write. When he returned to Argentina, he dismayed his scientific colleagues by abandoning his research.

There followed several extremely hard years, as Sábato struggled to make his way in his new profession. El Túnel was not only a great success in Argentina, but was also spotted in France by none other than Albert Camus. The book was immediately hailed as an expression of South American existentialism.

In Argentina, Sábato became part of the intellectual elite around Victoria Ocampo and her literary magazine Sur. He met and became close friends with Jorge Luis Borges, with whom he shared doubts about ideas of progress and scientific certainties. However, the two men fell out after the 1955 revolution that overthrew President Juan Perón: Borges was fiercely anti-Peronist, whereas Sábato typically went on the radio to defend Peronist intellectuals who were attacked by the new rightwing regime. It was only many years later that the two writers were reconciled, and renewed a fruitful dialogue.

Sábato expressed his moral pre-occupations in books of essays such as Uno y el Universo (One and the Universe, 1945) and Hombres y Engranajes (Men and Gears, 1951). Internationally, he did not achieve the reputation enjoyed in the 1970s by Borges or younger writers such as Gabriel García Márquez, as his fiction was so plainly not of the exotic magical-realist school.

It was in the 1980s that Sábato was called upon to play his most important public role. After the collapse of the military regimes and the return of democratic civilian rule, President Raúl Alfonsín set up a commission to investigate the allegations that thousand of Argentinians had been forcibly "disappeared" and killed during military rule from 1976 to 1983.

Although in other countries the selection of Sábato to preside over the commission might have seemed ludicrous, there was no doubt that a writer of fiction represented the best hope Argentina had of finding an impartial figure who could be trusted to weigh the evidence and not adopt a political position. Sábato's preface to the ghastly testimonies, included in what was called Nunca Más (Never Again, 1984), was a model of outraged sobriety and a clear statement that respect for individual human rights must be the cornerstone of any decent society. The commission concluded that at least 9,000 people had been unlawfully killed by the Argentinian state, and its findings formed the basis for the unprecedented trial of the junta leaders in 1986.

Perhaps because of these experiences, Sábato's later essays showed an increasing pessimism about the future of humanity. For him, the technological progress of the 20th century had not been matched by any spiritual advance, leaving people increasingly bereft and with an enormous sensation of inadequacy and loneliness. This sense of loneliness was brought home to him in his personal life by the deaths of his first son, Jorge, who was killed in a car accident in 1995, and of his wife, who died in 1998.

Sábato, who was also a painter, was awarded the Cervantes literary prize in Spain in 1984. One of his last books, Antes del Fin (Before the End, 1998), was both an autobiographical sketch and a spiritual testament, in which he concluded: "Only those capable of envisaging utopia will be fit for the decisive battle, that of recovering all the humanity we have lost."

He is survived by his son Mario.