Over seven tumultuous weeks of nationwide demonstrations and protests, beginning with the death of the sacked reformer, Hu Yaobang, on 15 April 1989 and ending with the movement's violent suppression on 4 June, an estimated 100 million people across China demonstrated in support of political reform. The movement was inchoate, contradictory and politically confused but it remains the biggest peaceful pro-democracy movement in human history. For the millions who took part, life would never be the same again.

Last week I listened to a man in his 40s unburden himself of a secret he had carried for two decades. He was a student leader in a major provincial city, and although he was arrested in mid-June 1989, he was released after a month of enforced confessions. He moved to another city and eventually made a successful career. But for 20 years the burden of the hopes that were shattered on 4 June, and the apprehension that he could be targeted at any time by a regime that never forgets and rarely forgives, has weighed on his spirit. It is part fear, part depression, part rage.

Some are still in prison. Others, in mourning, are still harassed. A few campaign openly for a reversal of the Communist Party's verdict that the movement was the work of "a small clique of counter-revolutionaries" who wanted to overthrow the party and the socialist system. Behind the few high-profile campaigners and dissidents is the much larger throng of those who still nurse memories too painful to discuss.

It's been two decades since that lone protester defied a column of tanks on Beijing's Avenue of Eternal Peace, before vanishing, never to be identified. Since that time, China has prospered economically. The party has embraced the market and traded the socialist system it claimed to defend for the pleasures of getting rich. Younger generations are vague about a movement that still cannot be publicly discussed or documented. But the suppression at Tiananmen continues to exact a high price: the constant falsification of history, a political system frozen by the fear of the people's judgment, and a leadership that sees the ghosts of Tiananmen wherever voices call for political reform.

Four years ago a cautious official commemoration of Hu Yaobang raised hopes that Tiananmen might finally be reassessed. Since then the party has stalled, perhaps waiting for the deaths of the chief perpetrators and beneficiaries, Li Peng and Jiang Zemin, before it begins to re-examine the single most traumatic episode of recent times.

Tiananmen marked the moment when the Chinese Communist Party relinquished its ideological claim on the loyalty of the people. After that, its message was material: as long as its citizens were content to leave politics to the party, the party would deliver prosperity. Superficially, it has worked - and the ideas so vigorously discussed in 1989 have given way to the truculent nationalism of new generations.

But China has a culture that honours its dead, and Tiananmen's dead are privately remembered by millions. Until the democracy movement of 1989 is acknowledged for what it was, a massive expression of popular demand for a government accountable to its people, the ghosts of the dead and nightmares of the living will not be laid to rest.

Isabel Hilton is the editor of online magazine Chinadialogue

'What happened that night reshaped my life completely'

Wuer Kaixi, 41, was a leader of the student protests and number two on the Most Wanted list. After the crackdown he fled first to France, where he was a founder of the Federation for a Democratic China, and then to the US. He now lives in Taiwan.

Two decades on, Wuerkaixi still slips between past and present tense as he talks about that night in June; still gulps and falters. "The tanks sounded enormous ... Bullets were in the air... The blood was very real. You can smell it. People's panic and anger... In the hospital the doctors' gowns were no longer white. And you knew it wasn't from just one person ... it was overwhelming."

What happened that night "has reshaped my life completely", he says. Outwardly, there is little now to connect him to the angry young man who became world-famous for rebuking hardline premier Li Peng and subsequently held second place on Beijing's Most Wanted list. Aged just 21, he was smuggled out of the country and fled to France via Hong Kong. Since the mid-90s he has lived in Taiwan, where he works for an investment fund, writing political commentaries in his spare time. He has not seen his parents for 20 years - they are not allowed to leave China - but he is married to a Taiwanese woman and they have two sons. "I'm more fortunate than other exiles. I have a home," he says.

Like many protesters, he had no history of political involvement. As a freshman at Beijing Normal University he shared the gloom that was spreading through China: the initial enthusiasm for economic reforms was waning as inequality crept in and political reform stalled. A failed student movement in 1986 had merely spurred the downfall of Hu Yaobang, the popular, reformist general secretary of the Communist party. News of his death three years later was "a spark thrown into a gunpowder keg". One thousand students rallied on campus. Drawn deeper into activism, Wuer Kaixi became one of the founders of the hunger strike as the student movement swelled. He was hospitalised but rushed back to the square when told that a government leader would come to speak to the students. He was still in his hospital gown when he confronted Li Peng: the images of him rebuking the premier were beamed around the world.

Wuer Kaixi insists it was not a stunt. They had hoped for real dialogue, he says, but arrived to find a government showcase, with TV cameras and Li's "never-ending monologue. It was the mentality of the government - an old man lecturing troubling youngsters. I said, 'This may be a little impolite, but we do not have time to go on like this.' Li Peng said he was sorry he arrived late and blamed the students for blocking traffic. I said, 'You were late not by 10 minutes but by one month.'"

It is to the credit of journalists, he says, that the footage was broadcast to the nation. Like the fan mail that filled a truck in the following days, it reflected widespread support for the students. But, like many of the original activists, Wuer Kaixi was already dismayed by the development of the protests as more radical voices gained increasing sway among the crowd. "We were no longer in control of the masses in the square. I felt it was the beginning of the failure," he says.

But Wuer Kaixi is still proud of "one of the most rational and well-organised and remarkable movements of all time in human history", and has little patience for critics. "I will always feel sorry for the victims. We were the student leaders and we survived - they didn't. But we have done our reflection. If anyone needs to be blamed, it is the Chinese government." Tania Branigan

'I feel I have to be doing something political'

Chaohua Wang, 56, was a student leader in the spring of 1989, and after 4 June was on the Chinese government's Most Wanted list. She is now a writer and editor living in Los Angeles.

Chaohua Wang was a key organiser of the protests but escaped with her life while many of her friends were killed. She still agonises over what went wrong. "Ultimately it comes down to the fact that we didn't have enough intellectual preparation to make meaningful demands," she says.

Wang may have survived but she made other sacrifices - a six year-old son she was forced to leave when she went into hiding before escaping to Los Angeles. She did not see him again for 15 years. Her father died, too, while she was in hiding. "He thought I would be imprisoned - he lost all hope."

In LA Wang worked as a cleaner until she had learned enough English to enrol as a an MA student at UCLA, from where she later earned her MA and PHD degrees. She set up a website and began writing political essays. "I feel I have to be doing something political, even if it's just self-comforting."

In 1989 she was two years into an MA in modern Chinese literature when she heard a man with a megaphone in Tiananmen Square asking for representatives from Beijing's 47 universities. Wang found she had one of the strongest voices. "During the cultural revolution we had been encouraged to be argumentative, to stand up and speak." She became part of the students' organising committee and oversaw the protests from beginning to end. The 27 April march where students and workers came together was the high point for Wang. "It was a huge demonstration of public will. But we had no plan - we stopped running events and events started running us."

The student leaders weren't eating or sleeping properly. Wang lost her voice. Her hair got so dirty she cut it off. When the military entered central Beijing, she was in hospital with exhaustion. She dreamed of New Year firecrackers. When she awoke, the ward was deserted. "People were sitting crying on the kerbs. The atmosphere in the city was more anger than fear."

In hiding, she saw her name on the government's "21 Most Wanted" list. If caught, she faced imprisonment or execution. She had no choice but to leave. The closest she has since been to China was in 2004 at Hong Kong airport, where she met her son, by then aged 21.

Tom Templeton

'Did we make any difference? I'm not sure that we did'

Shen Tong, now 40, was a leading organiser of the protests. He was on Changan Avenue when troops opened fire on the students. Days later, he fled to the US.

Twenty years ago, Shen Tong was 20. He was a thoughtful student at Beida University who became one of the main negotiators of the Tiananmen Square demonstration, co-chairing the committee on dialogue with the Chinese government.

"I always expected things to be harsh," he recalls when I meet him in the New York office of his software company, VFinity. But when the harshness came, even he didn't believe it. The person standing next to him on Changan Avenue collapsed and died and still he thought: "Oh, it's a rubber bullet."

People were bleeding in the courtyard of his home, being dragged on to roofs for safety, and yet, he says: "You somehow felt you were invincible. It took so long for reality to sink in."

Shen had been accepted to do a masters in biology at Brandeis University in Massachusetts; by means he still cannot reveal, he managed to collect his new passport, remain in hiding for six days and fly to the US, where he gave a press conference supplying the first eyewitness account by a student leader of the massacre. Months later, he was named one of its people of the year by Newsweek.

For the next 10 years, he worked tirelessly to raise awareness of human rights in China. Under the umbrella of his non-profit organisation, the Democracy in China Fund, he returned to China in 1992, testing Deng Xiaoping's assertion that students who had left would be welcomed. "Sure enough," he says with an ironic smile, "they put me away."

He was imprisoned for 54 days and released only after he became a figurehead for human rights as part of Bill Clinton's presidential campaign. "We're still too close to it to understand what happened," he says when I ask what 1989 achieved. "We're too close to the French Revolution, let alone to Tiananmen." Broadly, intellectually, he can say this: "If there is a simple answer, it highlighted the key question of how to keep in step with the rest of the world. Right after 89, the government said: we really need to justify the regime. A completely self-righteous totalitarian regime is much worse than a technocrat-run authoritarian regime justifying its legitimacy by some means that's close to human life, such as economic development."

Personally, though, his feelings are far more ambivalent. "Did we make any difference? I'm not sure we did," he reflects. "It's a huge price to pay: my youthful years, all of them. Second only to my own family, my beliefs remain probably the most important thing to me. But I don't know what to do with them."

He has done many things: he has written a memoir, Almost a Revolution; scholarly essays; film criticism; novels. He set up a TV production company and opened a bookshop. Then he hit upon the idea of using technology to empower people. Since the early 90s he had been involved in smuggling modems into China. Now he does business there officially.

In general, the people Shen knew in exile became very hard. He sought a different way of being: he has married and has two young children. They live in SoHo and collect art. Emphatically, he says: "I have a normal life. It sounds so basic, but among the exiles, that hasn't been basic at all." Gaby Wood

'In some ways no ideal is worth those human lives'

Diane Wei Liang, 42, is a detective novelist living in London with her husband and two children. Her books include The Eye of Jade and Paper Butterfly. She took part in the 1989 protests while a student in Beijing and fled to the US soon afterwards.

In Diane Wei Liang's smart Holland Park town house, a street away from the school where her children play with George Osborne's, the revolutionary spirit of mid-1980s Beijing seems impossibly distant. Impeccably groomed in skinny jeans with a shiny curtain of hair, Wei Lang has removed herself from her past in every possible way, changing not just her country of residence but her name, her nationality and the language she speaks. She renamed herself Diane as soon as she reached the west. Since then, she has renounced her Chinese citizenship and speaks only English to her children. She says her husband, a management consultant born in Germany, is upset they will not learn Mandarin but you get the sense that Liang is happy to put as much distance as she can between her new life and the one she led before the Tiananmen crackdown.

In 1989 she was 22, an academic high-flier, keen to escape her background and study in America. The daughter of two college-educated professionals, she had grown up in a labour camp where her parents had been sent with other "intellectuals". However, as some of her friends were politically engaged, Liang was drawn almost by osmosis into the pro-democracy movement which culminated in the massacre on 4 June. She marched, took water to the hunger-strikers and climbed up on top of a tank, pushing leaflets on its occupants.

She is not sure she would be as brave today. "It's in the Chinese culture to exchange blood for freedom, but I've seen the bodies and I've seen children being killed by a stray bullet, and in many ways I think that no ideal is worth those human lives."

She recalls the days following the crackdown. "China is a very noisy place but you didn't even hear children cry. Everyone was shut in. Soldiers' fingers were on the triggers, they shot windows when they heard an insult. Arrests were made. There were telephone hotlines - every day you worried someone would report you."

In those fearful weeks she was amazed to find that a passport application to study abroad which she had entered on the first day of the protests had been approved. Three months later she was in America with $40 and just a few words of English. A month later, in Virginia, she watched the Berlin wall come down.

Liang taught herself English, and took a PhD in business administration at Pittsburgh's Carnegie Mellon University. She became an economics professor and in the mid-90s was invited to teach on the very first MBA course in China, a measure of the direction the country had taken post-Tiananmen.

"When I arrived in Beijing I didn't know where I was, things had changed so much. I remember talking to my students about Tiananmen. It wasn't in the text books. Those who had heard of it simply knew the government version, but the rest knew nothing and weren't interested in it and they were not interested in leaving China either. Everyone just wanted to make money."

Liang married and moved to London where she took a post at Royal Holloway college, part of the University of London. While on maternity leave she wrote a memoir of her childhood in the labour camp and her role in the Tiananmen protests called Lake with No Name. This started her down the road to becoming a full-time novelist, fulfilling a childhood ambition. It has been a long and twisted road.

Tom Templeton

'When I saw the first dead body I felt cold in my heart'

Wang Juntao, 50, ran an independent thinktank and published an underground magazine in China in the 80s. He was an adviser to the student leaders and spent four years in prison following the protests before going into exile in the US.

Wang Juntao, one of the most influential thinkers behind the pro-democracy movement in China, was born in 1959, just as construction on Tiananmen Square was nearing completion. His father was a Party general; Wang's given name, Juntao, means "billowing wave of the army". After the events of 1989, Wang was arrested, held for 13 months without charge and eventually sentenced to 13 years in prison for his alleged work as a "black hand", or evil mastermind, of the student demonstration. In prison he contracted hepatitis B and, under pressure from Bill Clinton, the Chinese government offered to send him to the US for a medical exam in 1994. Upon his arrival, he heard himself being called an "exile"; only then did he understand that he could never return.

"Although I lost an opportunity to promote democracy in China, I got a chance to find out about other countries," he tells me when we meet in a Starbucks in New York City, near where he now lives. "And in the future, that will be very helpful to China. When I saw what was happening in Russia and other Soviet countries in the early 1990s, the transition was not too good. Nobody prepared how to deal with the transition - it was just thought, 'When the transition happens, everything will be better.' But it's not true. On the one hand the political system is much better than before, on the other hand the social and economic situations were not good."

Wang has spent the intervening years studying the matter closely, completing a Masters at Harvard and a PhD at Columbia. Inflation, corruption, military coups, American foreign policy and, above all, the rise of neoconservatism in China since the death of Deng Xiaoping: all of this has come under his intellectual lens. Now he has had offers to teach at many universities, including Oxford.

In Beijing Wang was a charismatic figure. He was a poet who co-founded the country's most professional pro-democracy magazine, Beijing Spring, and throughout the 1980s he campaigned on university campuses, held non-violent demonstrations, established a thinktank. He was methodical and patient, and had Deng Xiaoping's tacit support. So why was he imprisoned?

"They didn't follow our ideas," he says now. "I tried to give them some advice, but the students wouldn't listen to me. I told them very clearly: 'You want democracy? We need to very carefully defend what we have built.'"

He wasn't angry with the students: "I think they did a good job: their demonstration was large-scale and peaceful, their slogans were carefully thought out. But when I saw the first dead body lying in the middle of the road, I felt cold from my heart to my feet. I knew that everything we had worked for was over. The last chance of peaceful transition in China: over. In the west, you think we lost one battle. We lost more than that - not just lives, but opportunity."

Though he cannot go back, he has a vast amount of knowledge, and every other Friday he circulates a "powertalk" - a speaking PowerPoint presentation - in China, continuing to influence the grass roots from abroad. As for the future, he suggests, it is unknown: "The road to democracy is long, and paved with many stones. We don't know where we are in the road."

As we are leaving, Wang looks around the crowded Starbucks and shrugs with an expression of something like distaste. "To be honest," he says, "I don't like democracy. In fact, I hate it. I don't like the food, the clothes ... my ideal is a traditional Chinese one, of sitting in a boat on a lake in the moonlight, with some friends and a drink. But," he concludes, "I think people deserve their rights, and I've spent my life paying for them."

Gaby Wood

'We didn't have the experience to feel fear'

Wang Dan was a key organiser of the democracy protests. Made China's number one Most Wanted after the crackdown, he spent 10 years in prison. He fled to the US and is now studying at Oxford.

It seems absurd that a skinny, bespectacled student who had barely turned 20 should be ranked number one on a Most Wanted list of leaders sought for "counter-revolutionary rebellion" - but Wang Dan was portrayed as the mastermind behind the events of 4 June.

In fact, he was not. But his resistance to the authorities endured even after his arrest and imprisonment. When he left prison in 1993, he was certain he would return. "I already knew there would be a second time, because I didn't want to give up and the government would not be tolerant," he says. "With the student movement in '89 we didn't achieve anything and friends lost their lives. I had an obligation to continue their dream."

Studying at liberal Beijing University, he had already created a democracy salon, and was naturally drawn into protests the following year. "We were very young - I don't think we knew the true meaning of democracy," he recalls. "We hoped we could have freedom - not necessarily the right to vote, but a free life. That was our understanding."

One event in particular proved a turning point that spring: the now notorious People's Daily editorial accusing the students of creating turmoil. Intended to cow protestors, it instead provoked huge demonstrations.

"It was the first time when the government told people not to go on the streets and they went anyway. We were making history." Yet the demonstrators had little idea what they were getting into. "I don't think we were brave. We didn't have the experience to feel fear."

He was at the university when friends called him to tell him the military were shooting people in the streets. "For several days I was totally numb. I never believed the government could do this," he says.

While others escaped overseas, he stayed, still hoping that reformists would somehow triumph within the leadership. His arrest was an odd relief after weeks of hiding, though his family would bear the brunt too; his mother was jailed for 50 days. He plays down his own years in custody: "I was a special case - I drew attention from the international community. They didn't beat me. They treated me OK.

"Workers were put to death. The treatment of students was better than the workers and ordinary citizens; they were the real victims."

Freed in 1993, he was back in jail within two years, this time sentenced to 11 years for criticising the government and attempting to organise. US pressure won him "medical parole" in 1998, but his escape to the US was bitter-sweet, since he could not return to China. He completed his studies at Harvard and is currently a visiting scholar at Oxford. He remains an outspoken critic of the government.

Tania Branigan

'They didn't really believe the communist party could shoot them'

Chen Ziming, 55, (along with Wang Juntao) was labelled one of the 'black hands' behind the protests and sentenced to 13 years in prison. He has suffered poor health and his prison term was completed off and on in jail and under house arrest. He now lives in Beijing.

Chen Ziming is used to trouble. It began in his youth, in 1975, when he spoke out to support Deng Xiaoping – purged for a second time by Mao Zedong – and was sentenced to reform through labour. At the end of the decade, he helped to found the Beijing Spring magazine during a brief flourishing of political freedoms. Later, he took a leading role in experimental direct elections.

"I was first in prison in my 20s ... I had already decided to devote myself to a career of freedom and democracy in China. Although I was caught a few times later, these ideals established in my youth cannot be changed," he says.

In the mid-1980s, he launched the country's first private thinktank: the progressive Beijing Social and Economic Research Institute, which published the challenging Economics Weekly. But experience had made him wary as well as determined.

"Because of that, I acted very cautiously [in 1989]. I knew if I did anything, they would have something to say about it."

He was not cautious enough. He spent 13 years in prison and under house arrest as one of the "black hands" blamed for the Tiananmen protests. To this day, police watch his flat in the Beijing suburbs. "Nothing to worry about," he says calmly. Now in his 50s, Chen is hardly a firebrand, but very much the academic. He speaks in long, carefully structured paragraphs with numerous elucidatory clauses – and a hint of humour.

He says that in 1989 he simply offered advice to inexperienced students who had sought his help, as reformers in the leadership leant towards dialogue (others suggest that downplays his role, but stress he was a mediator between parties, not a leader).

"What happened next was really out of our expectations. Zhao Ziyang [the pro-reform general secretary] lost his job and people like us were put into prison. It wasn't a preordained outcome," he maintains.

"[The student leaders] were naive. They didn't really believe the communist party could shoot them or put them in prison ... Sadly, because there's no article about 6/4 [the date of the crackdown] allowed on the net, no publication about it, students of this generation possibly could make the same mistakes."

He was at home when the shooting began: "Of course I felt very angry. Most of the Beijing citizens felt angry. Our neighbours gathered to talk about events and an old lady said, there have been three changes of dynasty [from the Qing to the Republic of China, the Japanese invasion, and the People's Republic] and they were not as bloody as this."

Soon afterwards, the authorities released the "most wanted" student warrant and another naming leading intellectuals. Chen, warned that his name would appear on the second list, had already fled but was caught in southern China. Others had escaped overseas.

"I felt I hadn't done anything wrong or broken the law so of course I could stay in China. Both me and Wang Juntao [his long term friend and colleague, now living in the US] had experience of being in prison so neither of us was that scared of it. The government had to send some intellectuals as scapegoats, so we thought, why don't we take that role?" he says.

He had no idea how long he would serve, "but I thought, they even shot students in the square, so it couldn't be short. My wife was imprisoned for 400 days as well ... She was told that it was uncertain whether her husband would live or not." He thinks that attention from the international community helped to lighten his sentence.

Chen acknowledges the "great progress" made in his years in detention. But while economic freedoms have expanded, he thinks political rights and freedom of expression have been squeezed. In 2004 he won permission to set up the Reform and Reconstruction website with a friend – but once it garnered a following, it was shut down. Now hosted on a foreign server, it cannot be accessed from China.

"Even before 1989, you could have private publications ... Our comments and content were much more independent and better than the ones they have now and the central government never really bothered us about what to write and not to write," he recalls. "Now they have very strict controls. Where is that free spirit of the past?"

Tania Branigan

'The government finally and totally lost their legitimacy'

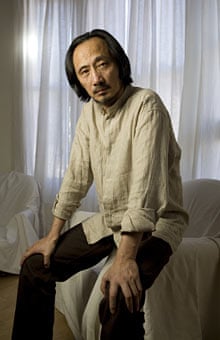

Ma Jian, 55, is a novelist. His books include Red Dust, The Noodle Maker and Beijing Coma. He spent six weeks in spring 1989 living with protestors in the tent city in Tiananmen Square. He now lives and writes in London.

Ma Jian has travelled a long way during the past 20 years but his heart remains in the country he has left behind. "Living in London is like being on a luxury cruise liner," he said recently. "It's very comfortable but I'm not in control of where it's going and I don't have both feet on the ground. This is something I can only ever feel in China." Ma is allowed to return to China but with the proviso that he does not speak in public. His books are banned there.

They were already banned and branded as "spiritual pollution" long before the Tiananmen crackdown: he had spent years travelling through remote parts of China adopting various identities to avoid police surveillance before he arrived at the tent city. After the protests, he feared for his life and fled to Hong Kong. Then, when censorship was ramped up after the 1997 handover, he moved to Germany. A year later he decamped to London where he now lives with his wife, the translator Flora Drew, although he still speaks very little English. Described by Nobel laureate Gao Xingjian as "one of the most important and courageous voices in Chinese literature", he has written on many subjects during the past two decades but it was only recently that he felt able to draw on his experiences during spring 1989.

The resulting novel, Beijing Coma - translated into English by Drew - was published last year to wide acclaim. It tells the story of a man who lies in a coma for a decade after being shot in the events of 1989, his mind racing while his country falls collectively into a stupor. This, in Ma's view, is what has happened in China over the past 20 years: despite the apparent loosening of restrictions, he feels he has witnessed the "stupefaction of a nation".

"Although on the surface much seems to have changed the thought control still exists," he says, over tea in a Kilburn cafe, "In essence nothing is different. The Chinese people have grown a hard protective shell under which they hide their thoughts and ideas. Since the Tiananmen protests the universities have become the most heavily policed parts of society.

They are now hotbeds of hyper nationalism and love of the party," he says sadly.

Growing up in Quingdao, a sea port in south east China as a young Communist Party pioneer he was taken to watch public executions, saw his teacher beaten by classmates, and joined in book burnings.

"There was no space to form an objective critical attitude to what I was being fed," he recalls.

It was only through working as a photojournalist in his twenties that he "gradually awoke to the fact that what was happening was wrong."

Twenty years on, Ma still feels that the Tiananmen Protest was a triumph for the people and marked a sea change in the history of China.

"Differences in opinion about how things were done should not undermine the huge nobility of what occurred.

"With the crackdown, the government finally and totally lost their legitimacy. They don't even believe in themselves any more."

"And the Chinese people showed they would sacrifice their lives in the name of freedom."

Tom Templeton

Beijing Coma by Ma Jian is published by Vintage.

'I sued the government over my detention'

Shao Jiang, 42, is a PhD student in political science at Westminster University and runs a blog on Amnesty International's website in support of human rights in China. A key player in the protests, he was named on the notorious Most Wanted list and imprisoned repeatedly in China during the ten years following the Tiananmen crackdown.

Shao Jiang has devoted the last 20 years to honouring the lives of those who died in the protests of spring 1989. "My life doesn't belong to me anymore, it belongs to them," he says, referring to those who died in the bloody denouement of the 1989 protests. He is a small man with cropped hair, oval spectacles and a ready sense of humour. Perhaps as a result of the things he has witnessed he seems to see life as Kafkaesquely absurd and deadly serious at the same time.

He spent three months on the run following the massacre before being captured. He then endured 18 months of interrogation in detention centres from Guangdong to Beijing. "Like many students I didn't get beaten as badly as the workers, they were punished the worst."

When he was finally released he knew exactly what to do with his new-found freedom. "I sued the government over my detention, I wrote letters and essays and criticised the government's failure to reform politically. Too many people had died not to continue the struggle for political reform."

Regularly jailed, placed under house arrest, and trailed when free, Shao was unable to get a job, as secret police leaned on potential employers. They then tried to bribe him.

"They wanted to control me in any way they could, but I refused."

Shao eventually escaped China, first to Sweden and then to London, though he will not discuss the route, just in case it causes trouble for those who helped him. In 2003, working in IT and researching a PhD in China's underground publications, Shao heard that his mother had suffered a severe stroke. He received a message from the Chinese police that he could return to visit her if he renounced his former actions. "Of course I couldn't do it," he says, and smiles.

Shao's participation in the Tiananmen Square protests began back in 1985, a week after his arrival at Beijing University when he attended a debate headlined: "Why won't the government allow political reform?"

It was the opening salvo in a four-year battle between students and government, including arrests, blacklisting, sham elections, marches and rallies. At the same time Shao and his fellow students studied Locke, Montesquieu and Gandhi, the Prague Spring and Hungarian revolution, and Chinese thinkers Fang Lizhi, Wei Jingsheng and Hu Ping. After Hu Yaobang's death everyone headed to the Square.

"I thought we needed specific demands. As we walked I wrote down a list and checked it with my fellow students. When we got to the square we handed in and then shouted our demands at the Congress."

By the time the army advanced Shao and his friend Liu Gang had spent five days trying to convince people to leave Tiananmen Square: "I felt the best long-term move was retreat. I saw the army start shooting civilians. We had never imagined anything like this. To kill their own people, their own nationality. I helped get some of the wounded onto tricycles, to be taken to hospital. People shouted 'fascists' , 'murderers' – and were mown down.

"This guy wearing a white coat walked slowly towards the wounded saying to the soldiers, 'Don't kill me, I'm a doctor.' They shot him dead. It was truly terrible.

"Then the army said over loudspeakers that if people didn't leave by 7am they would clear the square by any means necessary, so we got the hell out. When I got back a friend said 'What happened to your T-shirt?' It had brains and blood on it. I don't know whose."

Tom Templeton