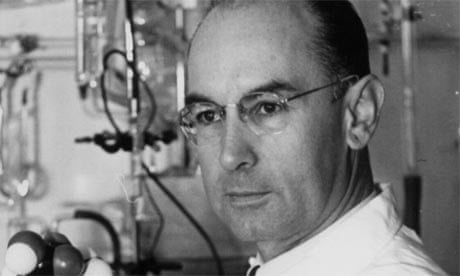

The first person to have a bad trip on LSD - and not even know why - was Dr Albert Hofmann, who has died aged 102. He was then an unknown chemist in Switzerland, but his discovery of the mind-altering psychedelic drug "turned on" a generation in the 1960s and changed the world.

Hofmann always maintained that LSD was an important tool for investigating human consciousness, but as "acid" it became a popular street drug. In 1966 it was criminalised by the US Congress due to its allegedly harmful effects. Other countries followed suit. For the rest of his life Hofmann worked for its rehabilitation, while arguing that it had the ability to advance the human spiritual condition. "I produced the substance as a medicine. It's not my fault if people abused it," he once said.

His discovery of LSD's awesome powers came on Monday April 19 1943 at his Sandoz laboratory in Basle, when he deliberately ingested a tiny quantity, 0.25mg, of a substance he called in German Lyserg-saure-diathylamid (lysergic acid in English). He was investigating the mild but curious sensations he experienced the previous Friday, when he had to leave his laboratory and go home after working with LSD.

What happened on April 19 became known to the psychedelic counterculture as Bicycle Day: Hofmann's wild, two and a half mile cycle ride home - no car being available because it was wartime - under the mind-bending influence of the powerful drug. He detailed the experience in his 1980 autobiography, LSD: My Problem Child. "I had to struggle to speak intelligibly. I asked my laboratory assistant to escort me home. On the way, my condition began to assume threatening forms. Everything in my field of vision wavered and was distorted as if seen in a curved mirror. I also had the sensation of being unable to move from the spot. Nevertheless, my assistant later told me that we had travelled very rapidly."

His wife and children were away and Hofmann lay on a couch, where his condition became alarming. "My surroundings had now transformed themselves in more terrifying ways. Everything in the room spun around, and the familiar objects and pieces of furniture assumed grotesque, threatening forms. They were in continuous motion, animated, as if driven by an inner restlessness."

The woman next door brought him milk, and he drank more than two litres. However, the neighbour was no longer "Mrs R", but a "malevolent, insidious witch with a coloured mask". He added: "Even worse than these demonic transformations of the outer world, were the alterations I perceived in myself, in my inner being. Every exertion of my will, every attempt to put an end to the disintegration of the outer world and the dissolution of my ego, seemed to be wasted effort.

"A demon had invaded me, had taken possession of my body, mind, and soul. I jumped up and screamed, trying to free myself from him, but then sank down again and lay helpless on the sofa. The substance, with which I had wanted to experiment, had vanquished me. It was the demon that scornfully triumphed over my will."

After a few hours the hallucinations disappeared and he went to bed, waking the next morning physically tired, but alert. Indeed, breakfast tasted better than usual and colours sparkled.

It later emerged that Hofmann's "bad trip" was because his experimental dose was excessive, so strong was the new substance. His employer, Sandoz, began producing the drug and it became popular in the US in the wake of the 1946 creation of the national institute of mental health and the burgeoning influence of psychiatry.

Cary Grant, numerous rock musicians and the "flower power" generation extolled its virtues. But it was exploited by self-publicists such as the Harvard professor and drug proponent Timothy Leary, who embraced it under the slogan "turn on, tune in, drop out". Hofmann met Leary in Switzerland but disapproved of him; he preferred the friendship of the late British author and psycho-investigator Aldous Huxley, whose writing on mind alteration he read.

Hofmann's interest in these phenomena led him in the late 1950s and early 1960s to isolate and then synthesise the hallucinogen in Mexican "magic" mushrooms, psilocybin. A shaman later pronounced Hofmann's pill version "the same".

He made a scientific investigation into the ancient Greek cult of Eleusis, suppressed in AD400 after 2,000 years, in which participants took a secret mind-altering plant ingredient. He and two fellow researchers concluded that the mystery elixir came from a substance similar to LSD. He co-wrote a 1978 book on it, Road to Eleusis.

Hofmann was born into a working-class family in Baden, a spa town in northern Switzerland, and as a child experienced memorable, revelatory encounters with nature. He entered the University of Zurich and graduated in chemistry, joining Sandoz in 1929 because it sponsored research into natural phenomena.

His work on chitin, a structural material in insects, became a thesis that earned him his PhD. Later, he began studying ergot, a fungus found on cereals that contains lysergic acid. He had actually discovered lysergic acid in 1938, but its properties were not understood and Sandoz dropped it. Hofmann's spontaneous return to it in 1943 was regarded by its enthusiasts as nature's gift during troubled times of war.

Of his momentous discovery, Hofmann later said: "We need a new concept of reality and a new set of values for things to change in a positive direction. LSD could help to generate such a new concept."

Hofmann retired from Sandoz in 1971. He devoted his time to travel, writing and lectures, which often reflected his growing interest with philosophy and religious questions. He remained active, going for walks in the small, picturesque village where he lived in the Swiss Jura mountains, a stone's throw from the French border. He spoke at a Basle ceremony honouring him on his 100th birthday. "This is really a high point in my advanced age," he said. "You could say it is a consciousness-raising experience without LSD."

He was predeceased by his wife Anita and is survived by two of his four children.

· Albert Hofmann, chemist, born January 11 1906; died April 29 2008