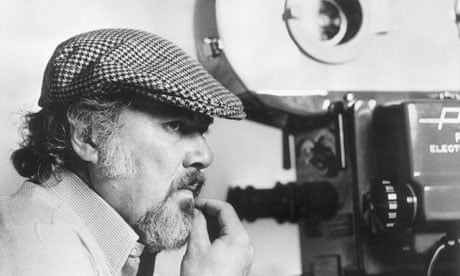

Success in Hollywood came late to the American film director Robert Altman, who has died aged 81. By the time he became a celebrity at 45, it seemed he had already settled into the role that suited him - the grand old man, cantankerous and wayward. He was compared to Fellini, as a creator of a cinematic world entirely his own, to Welles and to Stroheim. Like the latter two, he knew spectacular decline after glory, but unlike them, had a journeyman's pragmatism that allowed him to carry on, and more than once to resurface triumphantly. The actor Elliott Gould compared him to General Custer: "He always seemed on the verge of some sort of eternal defeat." Altman often went right over the verge of defeat, yet for observers of his career, an Altman low always presaged an eventual return to the heights.

He was born in Kansas City, Missouri, of English-German-Irish origins and a background he described as "renegade Roman Catholic". His father, an insurance broker, was an inveterate gambler; Altman grew up largely in the company of two sisters, his mother and grandmother. In 1941, he attended the Wentworth military academy in Lexington, Missouri, then joined the US army air force as a B-24 pilot.

After the war, he spent some time in New York, trying his hand as an actor, a songwriter and a fiction writer; one of his stories became the basis of Richard Fleischer's film Bodyguard (1948). He also briefly set up a business tattooing dogs for identification purposes. A long apprenticeship in cinema began when he returned to Kansas City and made industrial films; he made some 60 shorts, then tried his hand at commercials, and in 1953 made his first venture into television with the series Pulse of the City.

In 1955, Altman made his first cinema film, The Delinquents, followed in 1957 by a documentary, The James Dean Story, which brought him his first acclaim. He briefly directed on the television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, then spent six years in television, on series including Bonanza, The Millionaire and The Troubleshooters. Here Altman evolved a creative style and a flair for conflict with producers. He saw the adventure series Whirlybirds as "underground work", for the chance it afforded him to liven up programmes to his own agenda. He was fired from the war series Combat for including an anti-war script, and caused a scandal with an episode of the small-town drama series Bus Stop that was felt to be too explicitly brutal.

After a spell working on "ColorSonics", prototype pop video clips, Altman returned to cinema with the space drama Countdown (1967), and the psychological thriller That Cold Day in the Park (1969). He then took up an offer to direct a war satire that had been turned down by 15 others. M*A*S*H (1970), set in a military hospital during the Korean war, remains Altman's biggest commercial success, and immediately crystallised his style and attitude, with its corrosive stance towards US institutions, its farcical humour, distinct elements of misogyny and, at times, over-readiness to tilt at easy targets.

The improvisatory style he developed on this film brought him into conflict with his leads, Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould, who distrusted what they considered an anarchic approach; Gould later admitted he had misunderstood Altman's "pursuit of the imperfect moment". The film, which cost $3m, earned Twentieth Century-Fox some $40m; it was awarded the Palme d'Or at Cannes, and spawned a spin-off TV series that Altman felt was a travesty.

Immediately afterwards, Altman initiated a pattern that would run throughout his career - following a successful film with one that almost seemed calculated to deliver setbacks. Brewster McCloud (1970), mixing broad counter-culture satire and fairytale, lost him much of the credit M*A*S*H had won. Yet the follow-up, McCabe and Mrs Miller (1970), remains a masterpiece of the period, recasting the heroic myth of the old west as a sombre farce of failure and corruption, so mercilessly that John Wayne denounced it as corrupt. Neglected by Warners, it was dismissed until Pauline Kael persuaded several fellow critics to recant. Similarly iconoclastic, The Long Goodbye (1973) revived Raymond Chandler's honorable detective Philip Marlowe as an anachronistic sleepwalker in 70s Los Angeles.

Nashville (1975) was a panoramic view of America's country music capital, featuring two dozen lead characters - singers, politicians, media people, hangers-on. It was received, like many Altman films, as an allegory of America, but could also be seen as his most extensive attack on Hollywood and the hopeless dreams it sustains in consumers. Few mainstream American films had flown so defiantly close to the limits of narrative cinema, with Altman attempting to give the impression that things were happening entirely under their own steam. Actors were encouraged to develop their own parts, even write their own songs. Altman later referred to the experience as "trying to paint a mural in which the horses keep moving"; but also remarked that while his films seemed to just happen, everything always happened in a very controlled way.

Commercially, Altman's star continued to wane. Buffalo Bill and the Indians (1976), a Brechtian satire of western myths, fared badly in bicentennial year, and Health (1979) was never properly released, becoming one of several lost films, another being the futuristic Quintet (1979), which mystified his devotees.

Throughout this period, Altman showed a flair for executing wilfully uncommercial ideas. The low-key, cryptic Three Women (1977) was based on a dream. A Wedding (1978) originated when he jokingly told a reporter that for his next project he would simply film a wedding. Altman described the result as "a docudrama", in keeping with his rather disingenuous explanation of his work: "I create an event, then shoot it as if I have no control over it." What gave him a degree of control was the use during the 70s of a floating repertory company of players including Keith Carradine, Geraldine Chaplin, Michael Murphy, and, especially, Shelley Duvall.

Altman's fall from Hollywood grace came in 1980 with Popeye. At the time, the metamorphosis of Duvall and Robin Williams into cartoon characters mystified critics and public alike, and the film was regarded as a big-budget flop. Yet it has continued to earn on video and can be seen as a precursor of the big comic-book adaptations of the 80s and 90s.

Altman's already precarious standing in Hollywood was hardly improved by his willingness to publicly criticise people he disliked - stars, producers, screenwriters and critics. In 1981, he was forced to sell his production company Lion's Gate; only two years earlier he had expanded it into a full-scale studio, and used it to further the careers of directors Robert Benton, Robert M Young and Alan Rudolph, whose films he has continued to produce.

The 80s began badly. Altman's Broadway stage production of Ed Graczyk's play Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1981), was critically savaged; in 1983, he directed a teenage farce, OC and Stiggs, which was not released for four years.

Against the odds, Altman reinvented himself as a director of chamber cinema, making low-budget films from stage plays. Foremost was Secret Honor (1984), made while teaching at the University of Missouri; a one-man show for a benighted, paranoid Richard Nixon, it remains one of America's most daring political films. Other chamber films were Streamers (1983), Fool For Love (1985), and a screen version of Come Back to the Five and Dime (1982).

Briefly moving to Paris in the mid-80s, Altman also did some distinguished television work, most notably the satirical mini-series Tanner '88 (1988), scripted by cartoonist Garry Trudeau. Shot in documentary style, it charted a presidential candidate's campaign trail adventures, and left its stylistic mark on such TV series as Hill Street Blues and ER. The character and format were revived in 2004's Tanner on Tanner, which added to the mix Altman's satirical views on modish American documentary making.

Altman was much praised for Vincent and Theo (1990), an uncharacteristically stiff film which pictured van Gogh as "a poor schmuck who had a lousy life," as he put it. But the film that put him back in the spotlight was Hollywood satire The Player (1992). As with M*A*S*H, Altman made a success of a script that several directors had rejected: crammed with in-jokes and celebrity cameos, The Player was rapturously received by the Hollywood community, its vanity tickled even by scabrous mockery.

He followed it with the far more ambitious Short Cuts (1993), weaving Raymond Carver's short stories into a sprawling canvas of the petty comedies and tragedies of the Los Angeles lifestyle. He outraged Carver cultists by uprooting the stories from the author's Pacific North-West, by adding a new story of his own, and by using Annie Ross's sardonic lounge songs as a linking chorus. Short Cuts' narratives demanded more concerted involvement from the audience than any other American film of the 90s; and its blithely apocalyptic pay-off and decidedly cruel streak made Altman as controversial as he had been at his peak in the 70s.

It seemed inevitable that Altman would again fall from grace, as with the ill-received but spirited Pret-à-Porter (1994), a Nashville-style lampoon on the fashion industry. It was when he made a rare venture on to personal terrain that Altman came really unstuck. Kansas City (1996) revisited his boyhood, and his memories of jazz; the result was claustrophobic and strangely non-commital.

Altman's last decade, however, was as active, mixed and surprising as any in his career. The Gingerbread Man (1998) was a ramshackle adaptation of John Grisham's crime novel: Altman's apparent contempt for his source material led him to be anarchically inventive in a way entirely his own. While its follow-up, the ensemble comedy Cookie's Fortune (1999), seemed uncharacteristically benign, Dr T and the Women (2000), a farce starring Richard Gere as a Texan gynaecologist, was strident and cantankerously misogynistic.

A late-period return to form came with a venture on to new terrain - Gosford Park (2001). Shot in Britain with a blue-chip cast including Maggie Smith, Kristin Scott Thomas, Clive Owen and Helen Mirren, the film was a playful parody of the English country-house murder mystery. Juggling a sprawling range of characters, above and below stairs, Gosford Park cast a sardonic American outsider's glance at the English class system, although - given Altman's notoriously cavalier attitude to scripts - the film owed much to the British insider flair of its writer, Julian Fellowes. Gosford Park was Altman's biggest commercial success in years.

He followed up with further ensemble pieces. The Company (2003) was created in collaboration with its star Neve Campbell, and was a fictionalised portrait of life in the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago.

At the start of 2006, Altman's final film was premiered in Berlin: A Prairie Home Companion, based on Garrison Keillor's books and radio series. Its cast - including Tommy Lee Jones, Meryl Streep and Lindsay Lohan - showed again that Altman rivalled Woody Allen in his ability to muster big names for low-budget projects. Mixing fiction with real-life elements - the film's premise is that Keillor's radio show is being closed down - Altman's backstage (and onstage) comedy was acclaimed as a genial and elegiac tour de force, and received by some critics as Altman's knowing farewell to cinema. It is due for release in Britain next year.

It is tempting to think that the definitive Altman films might have been the many never made - EL Doctorow's Ragtime, from which he was fired by producer Dino de Laurentiis, outraged by Buffalo Bill; a long-cherished adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut's Breakfast of Champions; a biopic of Rossini; revisits to Nashville and Short Cuts; and a plan to make two films from Tony Kushner's Aids drama Angels in America. The films he did make were often flawed, sometimes wildly so, but rarely compromised by settling for mere industry standards.

Altman's wavering fortunes have conferred on his career a sort of quixotic nobility. He contributed to his own problems, not only by his individualism and candour, but also by the gambling streak he shared with his father, and which was not exclusively extra-curricular. He was a seasoned drinker - "I don't drink while I'm working," he said, "but I work a lot while I'm drinking" - and womaniser, although his marriage to third wife Kathryn Reed, his partner since 1958, is one of the film world's more enduring matches. She survives him, as do their sons Robert and Matthew, and his daughter Christine and sons Michael and Stephen (a noted production designer) from his two previous marriages.

Altman was always reluctant to identify his influences, and it is hard to see which film-makers he has left his stylistic mark on, other than Alan Rudolph. It would be hard for anyone to "do" Altman, since his style seems to be as much about attitude as what is on screen. The seemingly ragged approach he developed in the 70s, the moves towards democracy among actors and crew - but certainly not writers - made for a circus-like, medicine-show feel, which justifies the comparisons with Fellini.

His finest films, while they clearly address the world outside them, created their own distinctive atmosphere. Acclaimed for his critique of American culture, Altman always denied having any particular agenda: "I research these subjects," he said, "and discover so much bullshit that it just comes out that way."

It has been said of Altman that he was "ennobled by failure and oppressed by success", which would explain his unpredictable moves and idiosyncratic reading of his own career - he continued to defend Pret-à-Porter while dismissing The Player as "a fake film". Pauline Kael said: "Altman's art, like Fred Astaire's, is the great American art of making the impossible look easy." More than that, he made the alarming vagaries of his own career look like a rollercoaster joyride.

·Robert Altman, film director, born February 20 1925; died November 21 2006