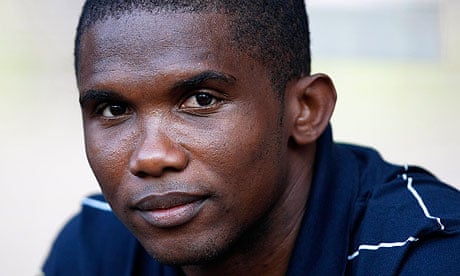

"It's incredible," Samuel Eto'o says as a dazzling smile lights up his usually serious face and he bangs a table in exultation. "I've always had this dream of playing in the World Cup in Africa and it's about to become a reality. When I'm in South Africa it will be the same as if I'm back in Cameroon. I've always said that, even before Cameroon, I belong to Africa. I might live in Europe but I sleep in Africa."

Eto'o speaks in impassioned torrents of French, sounding as poetic as he is fiery while explaining how his extraordinary journey merges with the wider story of Africa's first World Cup. After making his international debut the day before he turned 15 Samuel Eto'o Fils left Cameroon for Spain in 1996. He travelled from his hometown of Douala to Madrid, shivering in short trousers when he arrived at Barajas airport, lonely and frightened. "It seems incredible now," Eto'o exclaims again, reaching for his favourite word, "but then my whole life is incredible!"

• Sign up now and play our great Fantasy Football game

• Get the lowdown on every player with our stats centre

• All of the latest team-by-team news, features and more

• Follow the Guardian's World Cup team on Twitter now

His trial led to a contract with Real Madrid which ultimately entailed little more than him being shunted from one Spanish club to another. Eto'o was loaned out to Leganés and Espanyol and Mallorca before, finally, the last of those clubs bought him in 2000. Four seasons on, having won the first of three African Player of the Year awards, Eto'o moved to Barcelona. Despite suffering terribly from racism, Eto'o established himself as one of the world's great footballers as he helped Barcelona win three La Liga titles and two Champions League finals.

A few weeks ago, having been transferred last summer to Internazionale as the Italian club were offered Eto'o and €46m (£38m) in exchange for Zlatan Ibrahimovic, he celebrated his first season in Serie A by winning the treble – including yet another Champions League title as his work-rate and discipline proved crucial to José Mourinho's tactical masterclass.

"That's why I'm so proud to be African in this World Cup," Eto'o says. "Like most Africans I had to work much harder and show much deeper belief than others. I started with nothing and reached the level I'm at today. All I had was football and God's help. But I made it and now I'm going home, to Africa, where we can show a different face to the world.

"Most people only see Africa in terms of poverty and war, famine and disease. But this World Cup gives us the chance to show something different. I think the whole world is going to be really surprised by Africa. This could be the best World Cup in history."

Eto'o knocks on a wooden panel at Cameroon's pre-World Cup base in a French country retreat, 45 minutes north of Paris. "I'm doing that for luck but Africa is ready to show the world how much joy we can bring to this tournament."

An hour earlier there had been little joy in Eto'o. He had arrived at a round-table meeting with French journalists like a regal African prince. As he swanned through a sweltering conference room with haughty disdain it had taken less than a minute for Eto'o to display real anger. Eyes blazing, he responded to Roger Milla's recent suggestion that "Eto'o brought lots to Barcelona and Inter but never anything to Cameroon".

Milla, the star of the Cameroon side which became the only African team so far to reach the World Cup quarter-finals, when they lost to England in extra-time at Italia '90, was Eto'o's boyhood hero. But the very mention of Milla's name made him smack the table repeatedly so that a line of tape recorders toppled over in front of him.

"People should respect me and they must shut up because playing in the quarter-finals is not the same as winning the World Cup. My career does not just end in the quarter-finals. I've won the Olympic Games [in 2000], I've won two Africa Cup of Nations [in 2000 and 2002]. How many Champions Leagues have I won? I don't need to answer anything."

He was asked another tremulous question and, again, brought his fist crashing down. "I'm 29 years old and I've known glory for seven years. Is Roger Milla a selector? He must shut his mouth. The feelings I had for my idol mean that I can't say what I really think of him. But I've realised the facts and he hasn't made history."

And with that dismissive snort Eto'o stood up and sent a radio microphone spinning into the air. It struck a Frenchman in the face with sufficient impact to make even Eto'o pause. He held up his hand in silent apology, before striding out of the room.

A plan to use his communal exchange with the French press as a gentle warm-up for this, his only exclusive interview before the World Cup, seemed to have been obliterated by his rage. It was hard to forget that two years ago this month Eto'o had apparently head-butted a journalist.

This time, eventually, Eto'o was coaxed back into the hotel lounge – because he understood the significance of speaking at a Puma and United Nations Environmental Programme collaborative event to raise awareness and money for bio-diversity causes in Africa. It is an issue that means much to him. And then, in our interview, it was not long before his anger gave way to the sheer anticipation of playing in South Africa. Eto'o began to emerge as a far more engaging man – far removed from the seething figure he had been in a formal media setting.

But why had Milla so upset him? "It's the same before every tournament. We get some bitterness from older players. All the African teams came to Paris before the World Cup because we're sponsored by Puma. Puma want to build this unity between African teams and yet some of us are going our separate ways. That's a shame."

Milla's criticism was made with specific reference to Cameroon's disappointing Africa Cup of Nations earlier this year. "It's true we didn't do well," Eto'o says, "but we need to write a better history in this World Cup. It's time for us to prepare mentally because the World Cup is played as much in the head as your legs."

How closely had Eto'o followed Cameroon, and Milla, in 1990? He beams again. "I was nine years old and after every match I'd run around the streets of Douala. No one could catch me because I was so happy. Even after we lost to England I thought it was amazing. But watching that game again in later years, as I sometimes still do today, I think the world wasn't ready for an African team to reach the semi-finals."

Eto'o harbours a more personal resentment from his World Cup debut in France in 1998. He was the youngest player in the tournament, at 17, and he has not forgotten the experience. "It was very traumatising because we needed to beat Chile to make the second round – and we had two penalties which were refused. We were knocked out and France went on to win."

He leans forward animatedly: "The question we have all the time is whether an African team is able to win the World Cup. But the real question is whether the world is ready for an African team to become champions?"

Does he believe some officials might still subconsciously favour the more traditional European and South American powerhouses over the six African teams? "I'm still a player," Eto'o smiles. "I can't say that sort of thing. We've covered a lot of ground in the last 20 years and in Europe so many leading players are African. If we prepare properly, then one of the African teams can do something special."

As a reward for their qualification Eto'o presented each squad member with a watch reputedly worth €29,000. That's almost €700,000 worth of watches but Eto'o shrugs when asked about his lavish generosity. "It's a small present I'm giving to the national team compared to the joy they gave to our people."

€29,000 is still a staggering price for a watch – even for a diamond-encrusted galáctico such as Eto'o. "The amount of money I spend is not important. If I were Bill Gates I don't know what I would've given my team-mates because the joy people felt after that game in Morocco [when Eto'o's goal secured Cameroon's record sixth qualification for an African country] has no price."

The distance between such grand largesse and his humble arrival in Madrid 13 years before is stark. "I never forget it. In the moments before I went out for the Champions League final last month I thought about that day again. It helped calm my nerves and make me appreciate how far I've come. I came to Madrid on a freezing winter day, in short trousers and a T-shirt. I was with another African kid, a guy from Nigeria [Antonio Olisse]. He broke his leg and didn't make it. But we stayed in touch because I don't forget. It's always been a very tough journey for African footballers in Europe – and it's still tough today."

Eto'o was subjected to racism throughout his career in Spain. "I suffered a lot. I'll be a bit rude here but those who come to the stadium to whistle at me and make monkey chants and throw banana skins have not had the chance to travel and educate themselves like we did."

He sounds strangely polite, with the power of his words underlined by the civility of his tone. "I had to deal with it so often I found ways of making a point against racism. When we played Real Zaragoza they chanted like monkeys and threw peanuts on the pitch. So when I scored I danced in front of them like a monkey. And when the same thing happened against Real Madrid I scored and held my fist in a Black Power salute."

When he joined Barcelona he said he would "run like a black man to live like a white man". Eto'o nods at the memory: "People didn't really understand the deep meaning of my words. Some treated me as a racist but the reality was there. What I was trying to say is that [as an African] I need to do more than others to be recognised at the same level."

Will the first ever World Cup in Africa help eradicate these last festering outbreaks of racism in football? "I hope so," Eto'o says, "but I suffered a lot in Italy this year. So it's not just one country where there is racism. But to obtain these rewards you have to go through that. And that's why it's incredible we're playing in the country where my idol, Madiba [Nelson Mandela], lives. I've been lucky enough to meet him twice. I had the honour of being at his 89th birthday and had 10 minutes of private conversation with him. It was one of the most amazing things that ever happened to me."

Eto'o will lead Cameroon in two former Afrikaner heartlands with their first match next Monday against Japan in Bloemfontein before they travel to Pretoria to meet Denmark. Both teams are beatable and the schedule suits Cameroon because they will face the group favourites, Holland, in their final group match.

"We have a good opportunity but I'm not thinking of the quarters or the semi-finals yet. On paper Brazil and Spain are the best but in Africa we say, 'You can't give power – you must earn it.'"

Eto'o has earned more respect for his selfless play at Inter this season. "It made me extremely happy that, two months ago, Mourinho told me he needed me to do something particular. He wanted a very disciplined role and, because I respect him so much, I said, 'Yes, coach,' and stuck to my task exactly. These days you have to show that disciplined and tactical approach. It's not the same as the pure African football I played as a kid where you could be spontaneous. We must bring this same discipline in the World Cup."

Rather than not trying hard enough for Cameroon, as Milla implied, Eto'o has often attempted to do too much – constantly chasing the ball in an attempt to provide the individual magic missing from less illustrious team-mates. "It's different now. I'm the captain and my task is to inspire the team in another way. In the same way I hope I can convince young Africans to believe in their dreams. If you believe in something and have the strength not to give up, it can happen. I am the living proof it can be done."

Forgetting his spat with Milla, the flying microphones and even the extravagant watches, Eto'o signs a message for my son. "Tell him to keep dreaming," he says softly, full of warmth and hope, as if he might be talking to his 15-year-old self on the day he left Africa for Europe – with the dream that, one day, he would return to play in a World Cup and so complete his incredible journey.