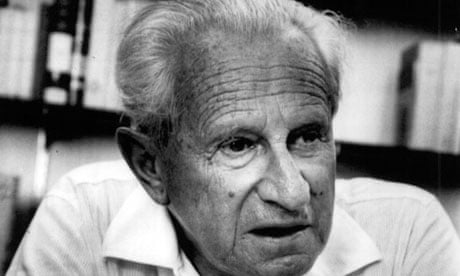

When the student generation took off in the 1960s across Europe, in Germany at least it was Herbert Marcuse who had the greatest influence. This is because whereas Adorno, with his highly pessimistic philosophical statements about historical development, could talk about a negative progression of humanity from the “slingshot to the megaton bomb”, Marcuse continued to maintain a more optimistic view of what could be achieved. Indeed, when 1968 happened, Marcuse said that he was happy to say that all of their theories had been proved completely wrong. Also, Marcuse wrote in a far more accessible way about the ways in which philosophy and politics were intertwined.

Whereas the French structural Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser had been at pains to draw a clear dividing line between early and late Marx, Marcuse maintained that the themes of the early works of Marx, concerned as they were with estrangement and alienation, were carried over and indeed deepened in the later, more economic texts. As he puts it: “if we look more closely at the description of alienated labour [in Marx] we make a remarkable discovery: what is here described is not merely an economic matter. It is the alienation of man, the devaluation of life, the perversion and loss of human reality. In the relevant passage, Marx identifies it as follows: ‘the concept of alienated labour, ie of alienated man, of estranged labour, of estranged life, of estranged man.’”

Marcuse linked economic exploitation and the commodification of human labour with a wider concern about the ways in which generalised commodity production (Marx’s basic description of a capitalist society) was at one and the same time creating a massive surplus of wealth through economic and technological development and an acceleration of the process of reducing humanity down to the level of a mere cog in the machine of that production.

How was it, Marcuse asked, that the totalising administered state, which he saw at work in western societies, got away with it? It did this through what he called “repressive tolerance“. This is the theory that in order to control people more effectively it is necessary to give them what they need in material terms as well as to let them have what they think they need in cultural, political and social terms.

Parliamentary democracy, he maintains for example, is merely a sham, a game played out in order to give the impression that people have a say in the way that society works. Behind this facade however, he maintained that the same old powers were still at work and, indeed, that through their tolerance of dissent, debate, apparent cultural and political freedom had managed to refine and increase their exploitation of human labour power without anyone really noticing.

Constitutional liberty and equality was all very well, he argued, but if it simply masked institutionalised inequality then it was worse than useless. As he put it in One-Dimensional Man: “Free election of masters does not abolish the masters or the slaves. Free choice among a wide variety of goods and services does not signify freedom if these goods and services sustain social controls over a life of toil and fear – that is, if they sustain alienation. And the spontaneous reproduction of superimposed needs by the individual does not establish autonomy; it only testifies to the efficacy of the controls.”

This instrumentalisation of humanity could only be reversed, Marcuse maintained, by challenging the social processes which had led the governing value system to change from pleasure, joy, play and receptiveness to delayed satisfaction, the restraint of pleasure, work, productiveness and security.

Drawing on Freud, he maintained that this switch from the pleasure principle to the reality principle was stunting human potential just at the point where the objective economic conditions for human liberation had reached their high point. Again, this is where Marxist historical materialism is married up with the dialectic – and he sees the two as inseparable – by pointing out that the switch from the pleasure principle to the reality principle was absolutely necessary for the development of civilisation but that, in the process, the Eros of human fulfilment had to be sublimated.

In this dialectical sense, civilisation is both a negative and a positive step forward. However, the positive civilising process cannot be seen as the end of the dialectic, what Francis Fukuyama later called “the end of history“, as long as the dialectic of human liberation was incomplete. As he puts it: “the true positive is the society of the future and therefore beyond definition and determination, while the existing positive is that which must be surmounted.”

It is easy to see how this forward-looking and optimistic philosophy could appeal to the political radicalism of the 1960s generation, and how the call for the liberation of humanity as both individual and collective could help to unleash new social movements who no longer had any faith in the ability of the traditional and conservative parties of the left to bring about significant political change in either east or west.

Next week I shall track back to take a look at the work of Walter Benjamin, the lost prophet of the Frankfurt school.