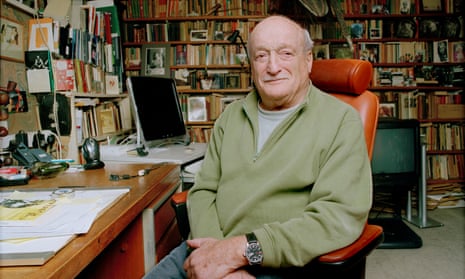

If one credits the title of his autobiography from 1999 – Where Did It All Go Right? – the word that best sums up the life of the writer, poet and critic Al Alvarez is “luck”. There is, however, a more appropriate four-letter word for the life he chose to live: “risk”. Not for him the percentage game. Alvarez, who has died aged 90 of viral pneumonia, confronted risk head-on in his favoured recreations – rock-climbing and poker – and in his career as an academic without a permanent post.

Alvarez was also, he claimed, a man without full nationality. “I am a Londoner, heart and soul,” he protested, “but not quite an Englishman.” His Sephardic Jewish family had been resident in the country for 200 years. Enriched in the clothing trade on the side of his father, Bertie, and property on that of his mother, Katie (nee Levy), they had been assimilated for generations. Although they were no longer quite as rich as they had been by the time Al was born, the family’s mansion in Hampstead, north London, retained a full complement of servants and a high level of cultivation. Classical music was, Al said, one of the great joys of his life even if, like his father, he could play nothing but the gramophone.

Al went to Oundle school in Northamptonshire. A brilliant pupil and a pugnacious sportsman, he excelled but narrowly escaped expulsion in his last year for wilfully breaking rules. In 1949 he went as a scholar to Corpus Christi College, Oxford, to read English. There, with like-minded rebels, he founded the Critical Society, whose manifesto opened: “In Oxford current literary criticism is both vague and ineffective.” Alvarez would be saying something along those lines all his life.

He took a first – the first undergraduate to do so in English at his college. But he disdained the conventional academic career his achievement made possible. He couldn’t take the “high-table chat”, he would airily explain. In more serious mood he felt that English, as practised at Oxbridge, was like “geography” – a discipline for the clever but not the brilliant.

In his most serious mood Alvarez detected discreet institutional resistances. This was a period when Jews could find a niche in philosophy, as had Isaiah Berlin (who got the first “first” ever in his subject at Corpus Christi), or physics, but not the “national” subject. English was closed to the “not quite English”.

He chose to be an outsider. His adopted forename, “Al”, evokes the gunslinger rather than the Hampstead intellectual or the don. Free from “all that fiddle” (a term he borrowed from the admired US poet Marianne Moore) he embarked on a career in which he would do more to shake up English studies from outside than he ever could have done as a company man.

America recognised the authentic Al Alvarez quality early on. Before he was 30 he was invited to give the Gauss seminars on criticism at Princeton. As his longtime friend Frank Kermode ruefully observed, he had felt lucky to get the invitation at 50. There followed two conventional books, The Shaping Spirit (1958), on modern British and US poets, and The School of Donne (1961). They were done, one felt, to show he could do it. Just as well and better than the high-table eunuchs.

It pleased Alvarez to say that he made his first marriage, aged 16, to John Donne, on first reading Witchcraft by a Picture. His first proper union was with Frieda Lawrence’s granddaughter Ursula Barr in 1956. It forged an apostolic line with an author with whom he was, at the time, besotted. DH Lawrence, he later felt, was a bad influence and the marriage “a very bad marriage”. The couple divorced five years later. In 1966 he married, lastingly, Anne Adams.

As a rock-climber Alvarez was never in the first rank but, like Robert Graves, he wrote about the sport with a lyricism which better climbers could not aspire to. According to Matthew Norman, who played with him, he was a good poker player – but not world-class. Connoisseurship was Alvarez’s line, not performance. He was, he said, the only literary critic who wrote bestselling books about risky things. He also turned out three novels over the years written, as he quipped, to remind himself that he wasn’t a novelist.

A poet he most certainly was. But he never achieved the reputation his admirers felt he warranted. He was too busy with other things to work single-mindedly on his own career. He did much for the careers of other poets and even more to reshape received ideas about the form. As poetry editor of the Observer (1956-66), he used the post as a bully-pulpit to raise British awareness of such hitherto unregarded American writers as Robert Lowell and John Berryman.

His journalism fed into the polemic anthology The New Poetry (1962). Alvarez’s introduction opened with a declaration of war: “The London old boys’ circuit can be stupid, parasitic and conceited.” The mainstream of British poetry, he maintained, had been self-neutered by its deference to the “gentility principle”. He scornfully repudiated the “school of Hardy” and its tame apostles, John Betjeman and Philip Larkin.

Art, Alvarez asserted, was the product not of tepid Wordsworthian tranquillity, but the white heat of suffering, rage and self-destruction. It was a doctrine he labelled “extremism”. The New Poetry, he conceded, “earned me a lot of enemies. I intended it that way; it was a kind of fuck them.” It made the bestseller list and for Penguin (not Alvarez) much money.

Alvarez extended his go-for-broke iconoclasm in a series of programmes for the BBC entitled Under Pressure in which he travelled to eastern Europe and returned a passionate advocate for the poetry and literature being produced there – despite totalitarian oppression. It was a theme with him thereafter that Zbigniew Herbert’s not winning the Nobel prize was scandalous. Stockholm, like London, was stupid.

Ever restless, Alvarez enjoyed his greatest success with mid- and late-career books rooted in acute critical intelligence and raw personal experience – “fully existential criticism” he called it. The series kicked off with The Savage God (1971), a meditation on literary suicide. Its learned conspectus ended with the personal recollection of his own aborted and Sylvia Plath’s actual suicide.

Both occurred at the period when their marriages were breaking up. If he did not actually make Plath’s reputation as a poet, on the strength of her end-of-life “extreme” verse, Alvarez was its most effective proponent. They were personally close and he was among the last to see her alive. Despite the many accounts he gave of the relationship, its closeness has remained a matter of speculation.

The Savage God was another bestseller. Others in the “fully existential” genre were Life After Marriage (1982), a study of divorce; The Biggest Game in Town (1983), about poker in its capital city, Las Vegas; Offshore (1986), the record of a sojourn on a North Sea oil rig; and Feeding the Rat (1988), Alvarez’s homage to heroic rock climbing.

The self-exposure in these books was, even for Alvarez, risky. The London Review of Books gave his study of divorce to his first wife, Ursula, to review. The former Mrs Alvarez’s scathing retort ended: “I believe the description of himself, me, and of our marriage, to be a fiction. It is a pity he has neither the good taste, nor the talent, to present it as such.”

Friends were indignant on Alvarez’s behalf. He himself merely observed that in a divorce “everyone behaves badly”. Truth, he seemed to imply, might sometimes be a casualty.

He lived his last years where he had begun, in Hampstead. John le Carré, a fond visitor, described Alvarez at home as “an impassioned husband and a family man”. The Mind Has Mountains (1999), for which le Carré wrote that description witnesses the many warm friendships he kept up throughout life. Risky Business: Books, Poker, Pastimes, People (2007) is a collection of journalism exploring the lives of others who took their preoccupations to the limit, such as his neighbour the pianist Alfred Brendel.

Alvarez’s intransigence denied him many of the honours he deserved. He ignored the cold shoulder, “because I wasn’t part of that gang”. He was, however, given an honorary fellowship at Corpus Christi College in 2001. Whether his aversion to “high-table chat” had mellowed after 50 years is not recorded, though in Pondlife: A Swimmer’s Journal (2013), recounting how he kept age at bay through outdoor dips in the ponds on Hampstead Heath, he still viewed the literary world as “peopled by monsters”.

Anne survives him, along with their children, Luke and Kate. The son of his first marriage, Adam, predeceased him.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion