Julia Margaret Cameron was 48 when she was given a camera by her daughter and son-in-law in 1863. The photographs she made – working at first by trial, error and bossiness – were, she absolutely insisted, Art with a capital A. She ignored the carping of critics who put down her dreamy focus to technical incompetence, and reserved a special de haut en bas putdown in her memoir for the unfortunate lady who tried to commission a studio portrait, as if she were a mere commercial hack.

She was born 200 years ago in Calcutta, one of a gaggle of sisters by the name of Pattle, known for their charm, wit and beauty (though Julia was the plain one). The governor general of India once remarked that he divided humankind into “men, women and Pattles”. She married Charles Hay Cameron, a member of the law commission stationed in India. He was 20 years her senior and the possessor of a long white beard and snowy hair that tumbled down his back. He would come in useful as a model for Merlin, later. She raised five children of her own, five children of relatives and an Irish girl called Mary Ryan whom she had found begging on Putney Heath – and who would come in useful as a model for medieval damsels, later. (Ryan eventually married Sir Henry Cotton, whose ancestors had run the East India Company. According to Cameron’s account, Cotton fell in love with Ryan after seeing her in Cameron’s photograph Prospero and Miranda.)

For 11 years Cameron exploded with creativity. She was lucky: a rare Victorian woman whose talent was not entirely suffocated by domestic duties. Of course she had help: the camera was heavy and there were plenty of chemicals to deal with, and presumably it was servants who did most of the lugging about. Marta Weiss, who is curating a Cameron exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum this autumn, points out that a stray hand will occasionally be visible in a frame, holding up a drape. Cameron’s housemaid, Mary Hillier, clearly got roped in as a model all the time. Posing for Mrs Cameron almost certainly beat blacking the grates. She seems to have sat very still.

Cameron’s great-niece Laura Troubridge recalled her zeal. She would be “dressed in dark clothes, stained with chemicals from her photography, (and smelling of them too), with a plump eager face and a voice husky, and a little harsh, yet in some way compelling and even charming”. She and her sister would be recruited as soon as they passed through the door of Dimbola Lodge, the Camerons’ house at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight. The girls were dressed up as angels and had heavy swans’ wings fixed to their shoulders, “while Aunt Julia, with ungentle hand, touzled our hair to get rid of its prim nursery look”. Aunt Julia was not to be trifled with. “Once in her clutches, we were perfectly helpless. ‘Stand there,’ she shouted.” Tourists admiring the maritime views were not safe. They “were liable to find themselves bidden in a way that brooked no denial into her studio, where, a few moments later, they would find themselves posing as Geraint, or Enid, Launcelot, or Guinevere...”

Cameron’s unfinished memoir is called Annals of My Glass House. The glass house was only a henhouse converted into a studio, though the name has a fairytale ring. And it was a fairytale place, in a way: in it, Hillier the maid, became the Madonna or St Agnes or the poet Sappho, and guests were transformed into characters from Milton, or Shakespeare, or the Bible. It was here that Cameron toiled to create what she called “my first success”, a portrait of a girl called Annie, which she produced in January 1864. She wrote that “from the first moment I handled my lens with a tender ardour, and it has become to me as a living thing, with voice and memory and creative vigour”.

She described her path to her characteristic soft-edged images thus: “My first successes in my out-of-focus pictures were a fluke. That is to say, that when focussing and coming to something which, to my eye, was very beautiful, I stopped there instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon.” She was not the first or last artist to have found her voice through what many would regard as an error.

Her memoir perhaps exaggerates the swiftness of her transformation from ingenue to artist. In a letter to the astronomer Sir John Herschel, she acknowledged his influence: “You were my first teacher,” she wrote, “and to you I owe all the first experience and insights.” Responsible for some important early technical innovations, he had sent her some “Talbotypes”, early photographic images made according to a process developed by Henry Fox Talbot in 1841. Her close-up photographs of costumed men also owed something to the artist David Wilkie Wynfield’s habit of photographing his friends to resemble Titian portraits. She took a lesson from him, she wrote to Herschel, and “I consult him in correspondence whenever I am in difficulty”, which may have been onerous for Wynfield, for Cameron was a prolific letter-writer.

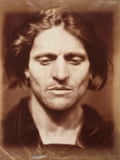

To Herschel, who is credited with being the first person to use the word “photography”, meaning, from the Greek, “light writing”, she presented in 1867 an album of pictures that will be shown at the Science Museum. It is interesting to see what she chose. Some images seem intensely modern. There is a portrait of an Italian man she calls Iago who seems to have stepped off a Prada catwalk. There are two dramatically lit headshots of her niece Julia. These pictures are easy to love.

Then there is the category of great men: Victorian patriarchs with facial hair so rampant it makes the efforts of today’s bearded hipsters seem lamentable. These men are strangers to personal grooming: here is Anthony Trollope, with lower face submerged in grizzled curls. Here is Herschel on whose wayward right eyebrow the camera has focused. Here are Tennyson and Henry Taylor, great poets in whose venerable beards birds could comfortably nest; here is the painter George Frederic Watts, gazing down through a dark waterfall sprung from his chin. “When I have had such men before my camera my whole soul has endeavoured to do its duty towards them in recording faithfully the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man. The photograph thus taken has been almost the embodiment of a prayer,” wrote Cameron to the historian Thomas Carlyle in her usual breathless prose.

Less easy to love, perhaps, are the tableaux and medievalist confections. A Study After the Manner of Francia has two girls gazing skywards in a saintly manner, one holding a branch of lily flowers. Photographs she made later to illustrate Tennyson’s Arthurian poem-cycle Idylls of the King can seem a little silly: solemn creations in which the costumes seem too redolent of the discarded curtain and dressing-up box. But maybe it is time to think about them – suggests Marta Weiss – alongside the knowingly composed groups of Jeff Wall, or the self-fashioning of Cindy Sherman.

It was the modernists who set the tone for the way we have long looked at Cameron’s photographs. The critic Roger Fry found the dressing-up-box groups irredeemably Victorian. Of a photograph of Watts’s wife, the artist Mary Fraser Tytler, surrounded by her sisters (an image called Rosebud Garden of Girls), he wrote: “There is something touching and heroic about the naive confidence of these people. They are so unconscious of the abyss of ridicule which they skirt, so determined, so conscientious, so bravely provincial.”

Fry was writing in a volume published by the Hogarth Press in 1926, to which Virginia Woolf contributed a spirited essay about Cameron. For she was the photographer’s great-niece. The beautiful Julia Jackson, subject of some of Cameron’s most arresting portraits, was Woolf’s mother – as one can easily see in those deep-lidded eyes and angular face. Woolf claims Cameron as an artistic precursor, of course, but also faintly ridicules great-aunt Julia – so earnest, such a worshipper of Beauty, so adoring of Genius. She wrote of her: “Dressed in robes of flowing red velvet, she walked with her friends, stirring a cup of tea as she walked, half-way to the railway station in hot summer weather. There was no eccentricity that she would not have dared on their behalf, no sacrifice that she would not have made to procure a few more minutes of their society. Sir Henry and Lady Taylor suffered the extreme fury of her affection. Indian shawls, turquoise bracelets, inlaid portfolios, ivory elephants, ‘etc’, showered on their heads.”

Woolf enjoys Cameron’s frightening vitality (she wrote poems and prose, too, until photography came along) but laughs at her style: “It is easy to see why Sir Henry Taylor looked forward to reading her novel with dread.” She makes her sound like a supporting character in Orlando, and supplies an almost magical-realist death scene in which Cameron succumbs in her bedroom in Ceylon (where the family moved in the 1870s). Birds flutter in through the open doors, the stars shine bright through the windows and Cameron dies with the word “beauty” on her lips. Woolf even wrote a play, for private Bloomsbury performance, about her – a comic frolic called Freshwater. In it, Tennyson sits for his likeness. “That’s the very attitude I want! Sit still Alfred. Don’t blink your eyes. Charles, you’re sitting on my lens. Get up.” Which is how I like to think of her – all energy, dash and indomitable talent.

- Julia Margaret Cameron is at the Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, from 14 August to 25 October 2015

- Julia Margaret Cameron: Influence and Artistry is at the Science Museum’s Media Space, London, from 24 September to 28 March 2016

- Julia Margaret Cameron is at the V&A, London, from 28 November to 21 February

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion