Many of Andy Goldsworthy’s best-known sculptures existed for less than a day. Despite being one of Britain’s best-known Land Artists, his ephemeral and intensely personal practice is more about what he can learn from the landscape than the monuments he can leave behind. Through decades spent watching the natural elements reclaim his painstakingly-crafted work, he has taught himself about life, death, and our place in nature.

Leaving the Studio: Andy Goldsworthy’s Early Life and Work

Born in 1956 in Cheshire’s Sale Moor, Andy Goldsworthy spent most of his young life on the outskirts of Leeds. He began working on nearby farms at the age of 13. This marked the beginning of his lifelong interest in agriculture, sculpture, and the human relationship with natural landscapes.

That nascent connection to nature found expression after a foundation year at the Bradford College of Art in 1974. Upon arriving at Preston Polytechnic to continue his studies, Goldsworthy was already finding the studio environment a bit too claustrophobic.

In an early echo of the New York Land Artists’ abandonment of the white cube gallery space, Goldsworthy left his studio for the sands of the nearby Morecambe Bay. There, he began the first of countless dialogues with nature that would define his career, creating sculptures with stones he found on the beach, then letting nature reclaim them. He described this: One day in first year I went out to the beach and dug things, made lines, and the tide came in and washed it away.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

It was here that Goldsworthy started using his work to better understand his own life and environment. Goldsworthy’s early works on the Lancashire coastline bore similarities to the Land Art that was being made by American artists thousands of miles across the Atlantic. A shared interest in making and installing works outdoors by using natural materials and minimalist shapes makes the movement a convenient art historical home for Goldsworthy’s practice. How well he fits the mold defined by the likes of Smithson, Holt, Heizer, and de Maria is another question.

Groundwork

The New York Land Artists certainly created some precedent for Goldsworthy’s practice. Earthworks, the 1968 exhibition at New York’s Dwan Gallery that announced the arrival of the movement, formed a break with conventional ideas about what (and where) an artwork was. By situating their work in remote rural landscapes, they undermined dominant modernist ideas about sculpture. The work of art no longer had to be in the gallery space, it was now being baked by the sun somewhere in the California desert.

Or was the work of art actually the photograph that Walter de Maria, for example, had taken of his Mile Long Drawing? Or was the real art lying in the act of creation, with Land Art being an extension of the Fluxus movement that had begun seven years earlier? These were the kind of questions that led modernist critics like Rosalind Krauss to pretzel entire frameworks to understand exactly what they were looking at.

Goldsworthy, who learned about Robert Smithson during his foundation year, developed a career against that backdrop. He asked those same questions:

[Photography] isn’t intended to replace the sculpture, and the sculpture’s not being made for the photograph. But the photograph is a very important result of the work. It’s the way I look at what I’ve made in the past […]

Whether the focus of art is in the sculpture, the act of making, or in the photograph, he needs that photographic record as documentation. Unlike those of many American Land Artists, most of Goldsworthy’s sculptures no longer exist.

Delicate Entropy

Goldsworthy’s work echoes Smithson and Michael Heizer’s interest in nature’s inevitable, cyclical decay, and regeneration. While works like Spiral Jetty and Double Negative insinuate themselves on the environment and deteriorate over decades, many of Goldsworthy’s are designed to disappear within a few hours. He is emblematic of a similar, but separate environmental art. The hyper-ephemeral nature of Goldsworthy’s oeuvre finds a closer fit with the work of British Land Artists like Richard Long and Julie Brook, who, for the most part, create sculptures that embed deterioration as a necessary act of completion, with nature as their co-author.

Goldsworthy’s leaf patches, Long’s lines, and Brook’s fire stacks are designed to disappear back into their environments and haven’t achieved their full exploration of the passage of time, impermanence, and cyclical transformation until they do so. Along with artists like Hamish Fulton and David Nash, their practices make a strong case for a category adjacent to Land Art. Theirs is a subtler intervention than the large-scale earthworks, lightning rods, and concrete pipes in America’s deserts. Instead of adding or subtracting, these artists rearrange and watch as nature rearranges in turn.

They are ecological in the technical sense, rarely introducing alien materials, they work with the elements of the ecology they find themselves in. There are major exceptions in each artist’s works, but they often resist the urge to create something as permanent as an earthwork in favor of sculptures that nature can more easily reclaim.

Nature as Co-Author

Goldsworthy works with that reclamation and passage of time at the front of his mind and as a means of understanding his broader experience. About one of his cairn-like cones, built next to a rising Canadian tide, Goldsworthy said:

I haven’t simply made the piece to be destroyed by the sea. The work has been given to the sea as a gift, and [it] has taken the work and made more of it than I could have ever hoped for […] I can see in that ways of understanding those things that happen to us in life that change our lives, that cause upheaval and shock.

He makes much of his connection with objects, moments, and places by spending hours, days, and weeks learning about the chosen environment and its materials. His efforts are often painstaking as he weaves, tears, dabs, and stacks, only for sculptures to collapse with gusting winds or shifting sands. He restarts when they do, so they can collapse or be blown away once finished, in their fullest form.

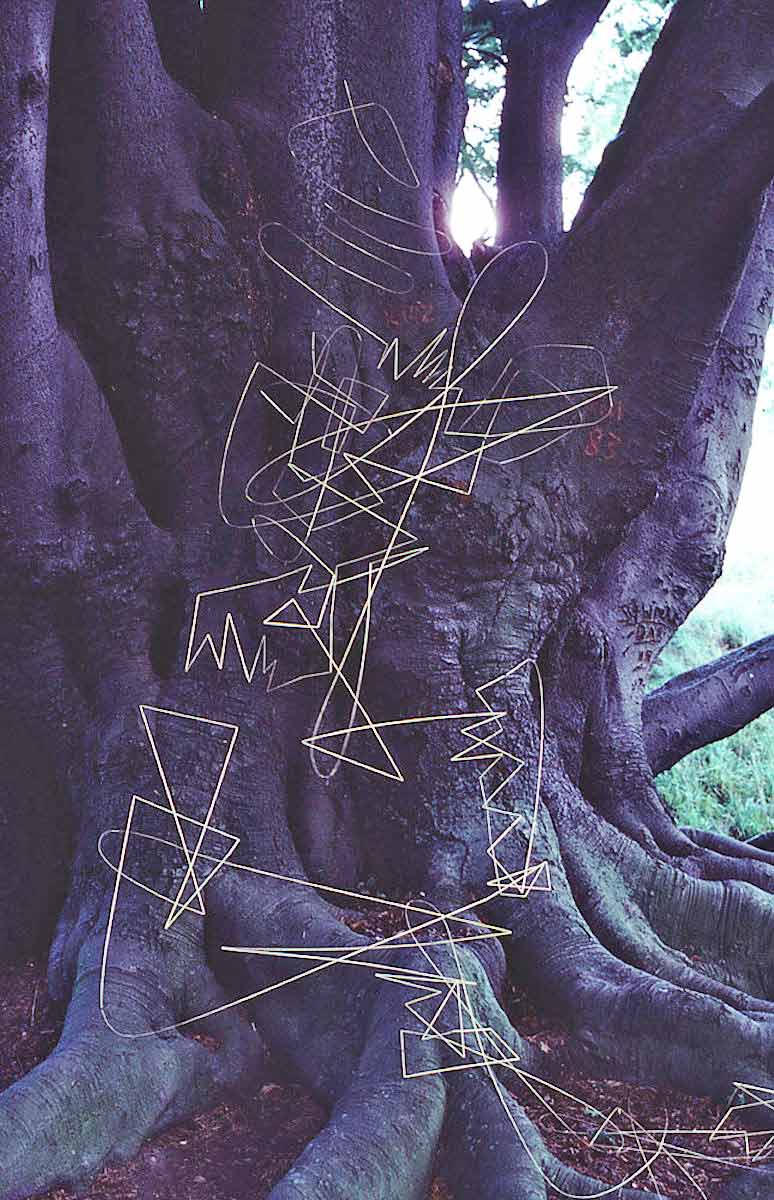

His is a tactile process of learning, responding, and improving. By the time he has successfully pinned a stack of grass stalks together with thorns or covered rock with delicate petals, Goldsworthy has managed to unearth energy. In some works, he uses color to signify that hidden essence. He describes the process as trying to think of [natural objects] not being a dead, inert material, but something that is alive.

In the process of doing so, Goldsworthy is teaching himself about time, transience, and life itself. If his works remained untouched and intact, they would be beautiful interventions and rearrangements of nature. When nature responds and whisks them away, they become profound, didactic markers of the inevitability of time’s passage, and its effect on the things we’ve given the most care in building and vesting our identity in.

Consolations of the Forest

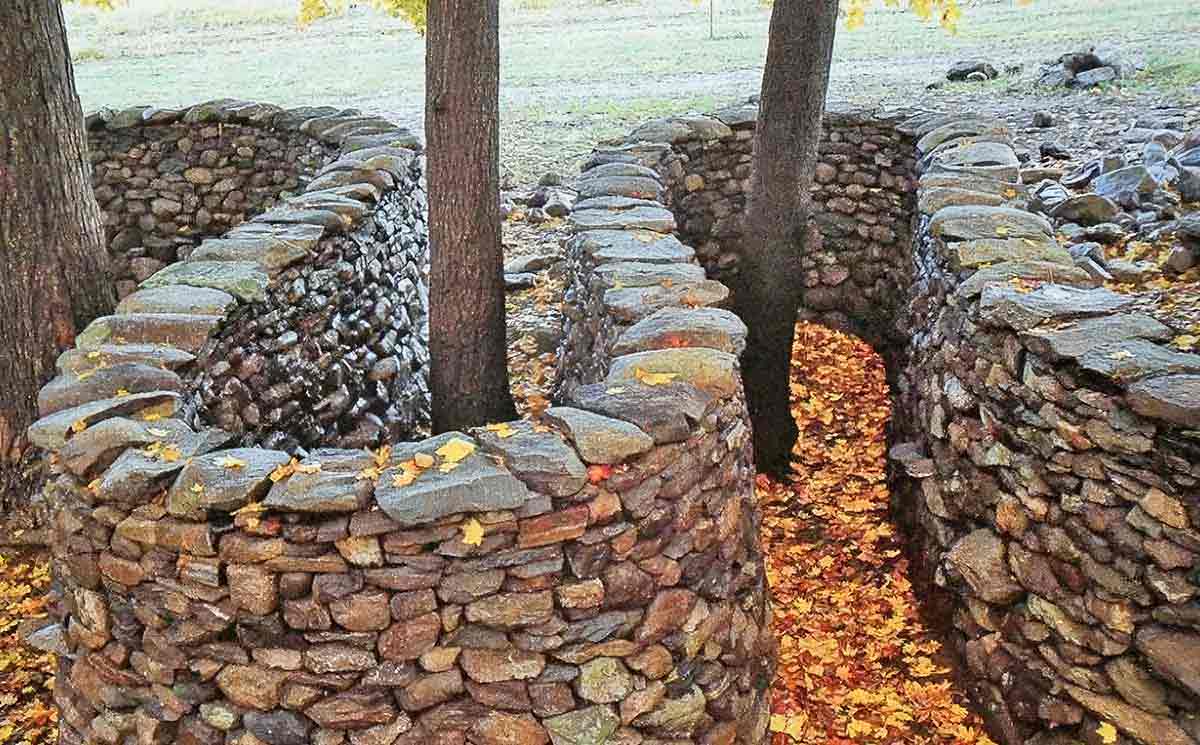

Goldsworthy’s work is his means of processing and understanding the world around him. As his life has developed and changed, so has his practice. With tragedy, he began to explore and make sense of presence and absence, a connection to the movement of nature, and humanity’s more explicit place in the environment and that cycle. The 1998’s Storm King Wall is an important fulcrum, marrying an interest in the life of his materials with a more permanent, human structure. Snaking through a forest in upstate New York, the drystone wall takes the form of a 750-foot-long tributary.

In Goldsworthy’s words, the surprising fluidity of the stone sculpture undermines his sense of what is here to stay, and what isn’t. The stone’s essence is continuous. Its solidity, which we take for granted, is not. Drystone wall-building recalls his early life on British farms, where the method was once a common means of separating tracts of land. Here, though, human intervention defers to nature’s blueprint, with the wall’s line defined by existing trees. Instead of interrupting, the structure now encloses and protects. It passes through and under a pond, and it is only stopped when it meets a highway.

Andy Goldsworthy’s Body: Shadows, Stones, Petals, and Leaves

Contending with the loss of both his ex-partner and mother in 2008, Goldsworthy increasingly mused on our connection and the inevitable return to nature in his Sleeping Stones works. The oval excavations were inspired by the 11th-century rock-cut graves he regularly encountered near Morecambe Bay. These were shaped to accommodate someone of his height. He reused the oval in his Refuge d’Art series, with the shape becoming something of a shorthand in his work for humanity’s inescapable immersion in nature, a portal between which the two can flow uninhibited.

Goldsworthy hasn’t abandoned ephemerality. Alongside his more durable stone works, he has continued to explore our impression on the landscape by creating rain shadows, a practice he began in the 1980s. Bringing Fluxus-style performance to nature, he lays down on gravel, pavement or rock when it begins to rain. When he gets back up, he leaves behind a dry patch that gradually disappears as the rain continues to fall.

In works like the rain shadows, Goldsworthy’s own body has become an artistic material in itself. This also happens in works where the artist coats his hands in leaves, spits petals from his mouth, or climbs through a hedge. As he contends with mortality, his work asks, and continues to ask: what marks do we make, which endure, and which fade?