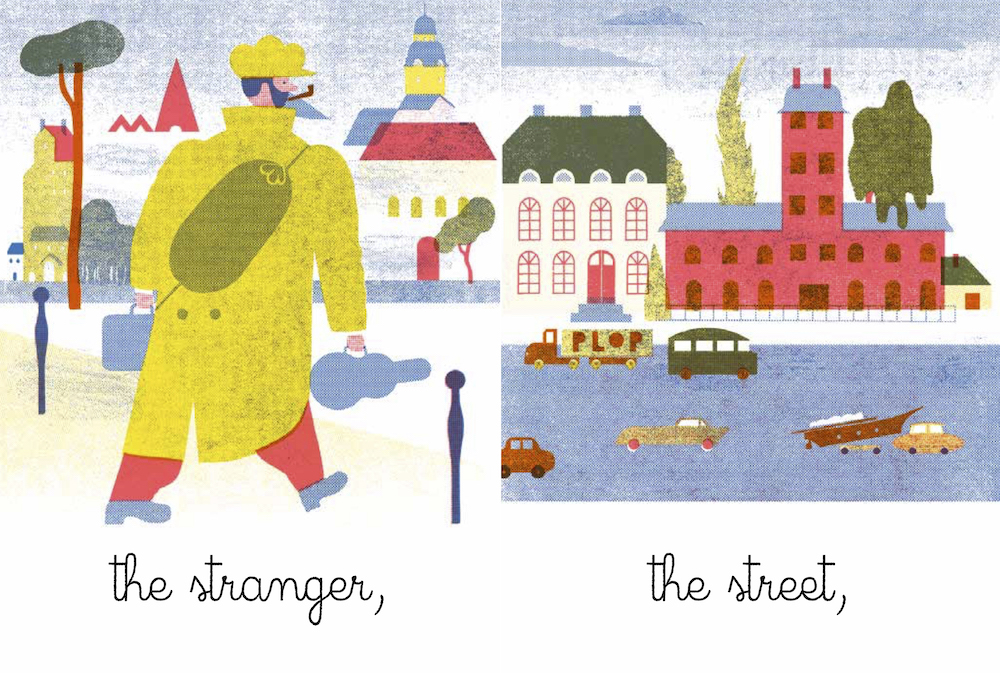

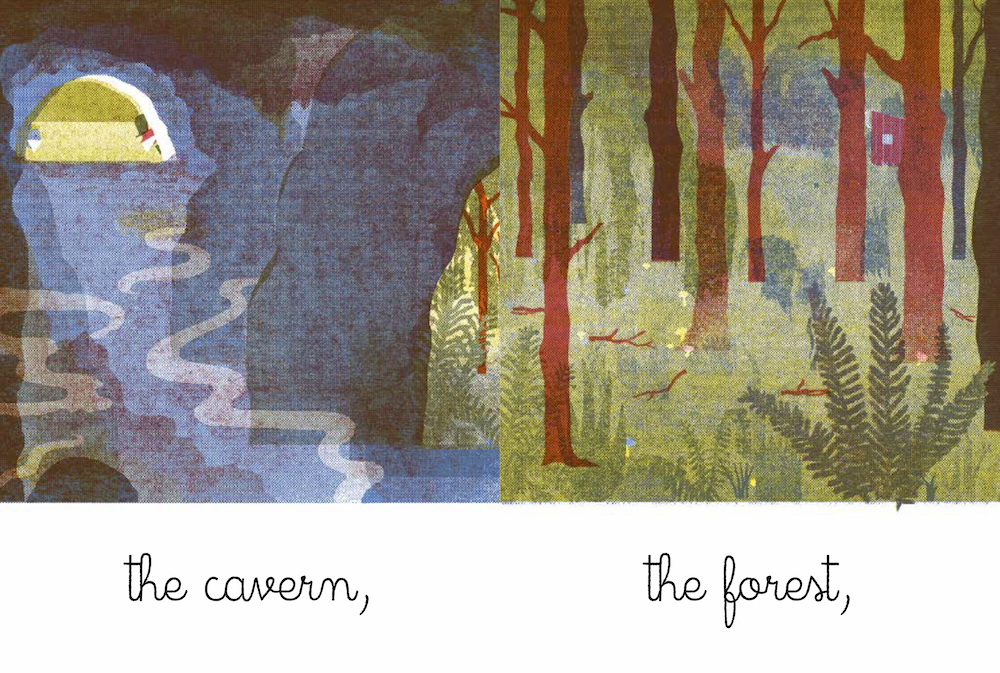

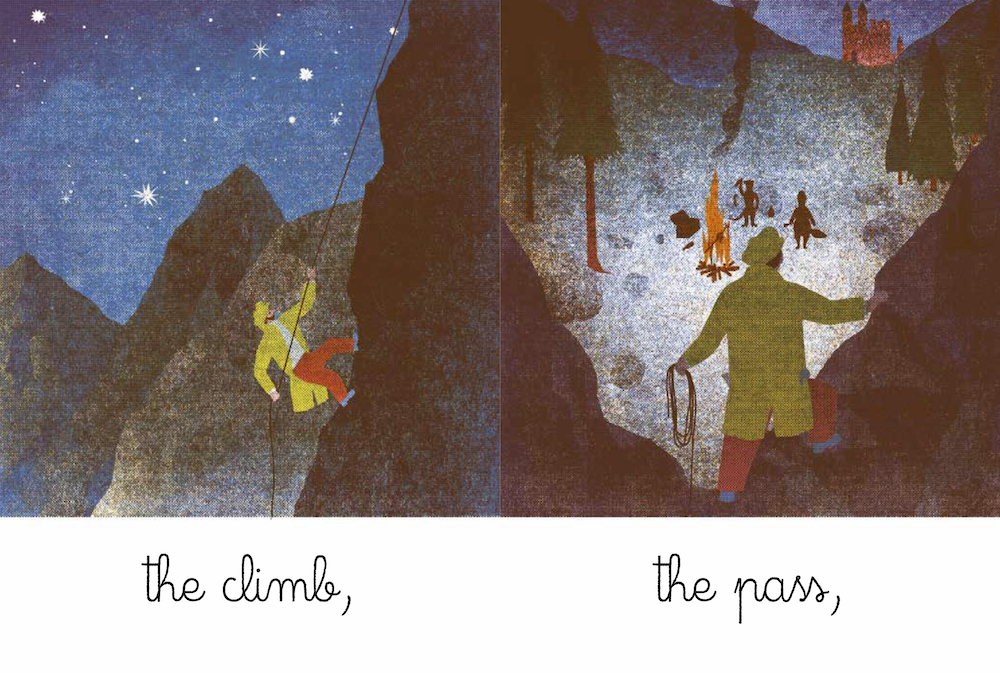

Blexbolex is an experimental printmaker and bookmaker revered for his distinctive approach to visual storytelling. He is the author-illustrator of Seasons, People, Ballad, Vacation, and many other works which playfully bend the conventions of narrative, as well as the formats of picture book and graphic novel. JooHee Yoon is an illustrator and printmaker whose complex and vibrant illustrations reinterpret existing poems and stories in picture-book form: Beastly Verse, The Steadfast Tin Soldier and The Tiger Who Would Be King. Her book Up Down Inside Out portrays familiar idioms in new and electrifying ways through innovation within the construction of the book itself. In this interview, which took place in the fall of 2017 as a prelude to the publication of Vacation in February 2018, these two highly original and wildly imaginative bookmakers discuss the book as object, "the trouble and magic" of childhood, and the word associations that create the underlying structure of Blexbolex's stories. Blexbolex's answers to JooHee's questions were translated from the French by Allison Charette.

* * *

BLEXBOLEX: Hello JooHee, and many thanks for your kind interest for my books and your questions about them. I will try to answer as honestly as possible. Sadly, my English far away from good and answering the questions in another language as my mother-tongue would be a too much difficult task. I hope that you won't mind it too much.

JOOHEE YOON: You have worked on many book projects, ranging from illustrating the cookbook I Know How To Cook by Ginette Mathiot to your own comics and graphic novels. Are children’s books something you’ve always wanted to do, or was it something that that happened naturally over the course of your career? (How did your first picture book come into being? Did a publisher contact you first or did you have an idea you pitched?)

I’ve loved books since childhood. Specifically, though, I’ve loved books as objects, more than for what’s inside, because a book might contain things that I don’t understand or don’t interest me.

But these strange boxes have always fascinated me, although I don’t know why. They only open one way (normally) and as a flat surface (usually), yet can be constantly refreshed whenever the pages are turned. My parents had many of them, but most of the time, I couldn’t make heads or tails of them. So, naturally, I focused on what the pictures had to offer.

Later, in the '70s, graphic novels became extremely popular in France. They had been before, but several innovations had made the media more interested in the people making them. That’s how some authors started becoming even more famous than their characters. Mœbius, the artist, represents that time period perfectly, and he’s certainly the most well-known. Jacques Tardi is another good example.

That was notable because it gave me a purpose for drawing. It’s a demanding discipline, drawing. I’d like to say that I enjoy drawing, but not beyond what my patience allows, and I have to admit that I have a bit of a deficit there.

So really, I love pictures, but not so much the way they have to be made. I often prefer other people’s drawings to my own.

I scribbled down my first book around the age of 13. It was a tiny, very thick book with lots of pages, kind of like those pocket-sized travel encyclopedias. I had one myself, and it was one of my favorite toys, one of my favorite things. That was also the era of fanzines, and I made several with a classmate, using the copy machine at school. Not too many people wanted to buy one from us, but that happens.

I’m sorry if this is a bit long, but I had to sketch out the background of that era before I could answer the other questions, because everything essentially follows from the context.

I did think about doing graphic novels for a living, and I focused my efforts to that end, but life had other plans for me. The larger context was changing in the '80s, without me really realizing it. New talent was always appearing, and my constant daydreaming couldn’t have helped anything.

Following the more or less sound advice of my professors at the Beaux-Arts school, I refocused myself toward the artistic sector. That was both a very good and a very bad thing. But enough about that.

Among the good things, the best was printing practice. First metal engraving, and then silkscreen printing. Learning those techniques allowed me to redirect my efforts and attention.

And later, I got to work as a printmaker, which was practically unheard of in the economic crisis that started to hit in the early '90s. The fact that I worked in a professional workshop helped me to print and publish my first books using the best possible materials, with—as much as it was possible—the same level of professionalism. I’ve never again had access to such good tools, which I’ve always been sorry about.

So, no: children’s books, like graphic novels, were never really part of the plan. Without a salaried job, I tried to do illustrations for the press, and that was a very challenging experience.

My enormously lucky break was the Un Regard Moderne bookstore in Paris, which sourced and sold that kind of “underground” work. Jacques Noël, the bookseller, was the reason for everything that happened afterward (not just for me): his strategies and support were unwavering and unstoppable, and everyone who worked in the business of making pictures stopped by the bookstore at one point or another. That’s how I slowly stopped being an unknown.

I owe him a lot. My debt is immeasurable, and I will never be able to repay him.

I remember seeing your books People and Seasons for the first time and being struck not only by the brilliant images, but the open-ended nature of the narrative. Even though a simple word accompanied each image, I felt the pictures related to one another through association and the reader was able to create their own story. What inspired this format?

It’s odd, actually. Although I think of myself more as an artist than an author, the instant I sit down to create something I always put some narrative element into my works. The graph’zines being produced in the '90s certainly didn’t require that. Quite the opposite, in fact: I very often thought it was a flaw that we could only produce images that had purely graphic elements. In fact, I should have shed that tendency—for, like in art, pure graphics should be clearly distinguished from narrative production (comics, movies, etc.) to make a true statement. I never managed it, and that ended up leading to a fair amount of misunderstandings and unfortunate consequences.

And yet, I slowly started to discover a picture-based language that was unlike graphic novels, films, or theater—it was more closely related to pantomime and could be best expressed through the curiosities that I spoke of earlier.

The form you refer to was certainly inspired by classic picture books. In People, I just endeavored to make it as clear and explicit as possible, perhaps a little more purposeful than what already existed. But I don’t really know, because I’m so far from knowing everything that exists in that category. Far be it for me to set down some sort of law. Rather, perhaps I presented it that way as if to say, “Look, here’s a picture book, it’s not some weird thing!” I wasn’t at all sure if that book would be received well or not, and I probably needed to just reassure myself, too.

Your sequences of associations seem very intentional even while there is an element of chance to them. How do you decide what to EXCLUDE? Given the specific nature of your included materials (e.g. for People: cat burglar, bystanders, corpse) how do you decide what to leave out?

Excellent observation. In order to make a book like this doable, it has to have a structure. A plan. Even if it’s not visible by the end, the book is divided into sections, and each section has a place in an overarching theme. In this case, the form I chose (or the form that chose me) was a spiral moving out from its center.

From that point forward, it becomes much easier to place each element, because they’re all part of a particular section. It’s impossible to show or say everything, so I have to choose what I think is best to illustrate each section’s ideas. That’s where I have to make difficult choices. Compromises have to be made sometimes, even if the book is already quite long for the type of publication it is. The subjects generally come to me from either my own childhood or my environment—whether my real and direct surroundings, my cultural environment, or my imagination. And they all depend on my own experiences, and thus on the limits thereof. I learned quite a lot about my own limits as I made that book.

The truly difficult thing here is not so much in showing, but in suggesting that what isn’t shown is in fact there. Excluding something from this book for whatever reason it may be... that doesn’t really mean anything. Otherwise, the book wouldn’t have any reason for existing. So we must conclude that what we see is only a tiny part of what exists, what has existed, what will exist. That is where the expressions between characters and figures are the most essential. That is the only true way that I have to express things, and it’s the only way that readers can overlay their own imagination and experiences, even if it’s as a critique.

But I have to decide, as an author or artist, what I will show: that is my risk, my responsibility, and my privilege. And I exist, too, as a human being. For better and for worse.

Is there an aspect of being an illustrator that you find difficult?

The fact that I have to keep going. Doing this work year after year is extremely difficult. I often doubt myself, but I can’t imagine switching to another career or line of work anymore, I’m too old.

Is it correct to say most of your work is created on the computer these days? You did traditional screen printing earlier in your career. Do you still? And what are your thoughts on working traditionally by hand vs. using digital tools?

Yes, the computer is a wonderful tool with many useful functions. That is also one of its faults, as all of the tasks end up feeling the same—I spend most of my time sitting between a keyboard and a screen, like most of my contemporaries. I continue practicing the traditional techniques to refresh my abilities, try new things, give myself room to fail without too many consequences. Reconnecting with the experience of failing, really, in a simple, bearable manner. That’s very important.

All tools are good tools. It’s more a question of mastery. Out of all the possibilities that are offered by the programs I use, I only work with a few of them. I want to focus on those until I find their limits. And once I find them, well, that’s when the fun begins, there’s something interesting about that, and I can start playing around.

I am a great admirer of not only your artwork, but your consideration of the book as an object and using the spot color printing process in making your books. Is this a natural progression from your experience with screen printing? Or were there other factors that contributed to this method of working with spot colors?

I imagine you’ll be able to figure out the answer to this question from my previous answers.

I’ll just add one thing, which is very significant for me. It’s a little complicated, because I don’t fully understand it myself.

For me, a book is like a painting or a piece of music. In composing or executing it, one must think not only of what it contains, but also of its form, of its volume, and of the methods used. You can never know enough about the paper, the printer, about the way that the images are prepared for printing, about the inks, the colors, etc.

Or about the book culture, or the people who make them, or about the reasons and methods of different people, etc.

I believe that one must at least try to be a proper artisan in order to become a good artist. But that’s probably a slightly classic vision of things. Perhaps a little idealistic, a dream of how things could be.

But that’s where real quality comes from and is expressed, I believe. And a note: sometimes amateur books or books by children are of such high quality, which is staggering to me. A great artist can be born anywhere and at any time, even if it’s only for one work. That’s what can be interesting, as well.

Do you make books with a specific audience in mind? Your books have wide appeal to both adults and children, so I’m curious to know how children and adults factor in for you. Do you trust children as readers more than adults because they are more open? Or do you just make work and trust that whoever needs to find it will?

Never. That would be a fatal mistake for me. Incidentally, I do sometimes think of a particular person when I’m making a book, but only for certain bits. I have other problems, like how to make a composition that will hold up, mostly. If I start thinking about other people at that point, I’ll be screwed.

I don’t trust anyone. I listen to what people have to say, mostly people I live with or my editor (of course) if necessary, but that’s about it. Otherwise, it gets too complicated. It might not be very nice of me, but that’s how it is.

My books aren’t intended for anyone in particular, so maybe they’ll be lucky enough to have someone find them.

I know you have worked for editorial and advertising clients. How do you view these projects in relation to your books? Do you prefer one more than the other? Do you find it hard to balance both? (I have found that it can sometimes be difficult when working on a book to be pulled out of the flow with quick deadline assignments. Do you find this to be the case? Would you say editorial work is a welcome break or a bothersome interruption?)

Ever since the beginning, this has been clear: illustration is how I pay my bills. Nothing to brag about.

Now, illustration work is interesting for several reasons. First off, it helps me keep in contact with the rest of the world. See what’s happening. Clients’ requests also usually make me get off the beaten path, either in form or content—sometimes, I have no idea what they’re asking, and I have to do some very interesting research.

An illustrator’s responsibility is not at all like an author’s. It’s shared, or nonexistent—it’s a contract and a commercial transaction with limited responsibility.

Sometimes, it can be a breath of fresh air to see the demands and specifications of the people I work with. It’s a rare occurrence, yes, but sometimes it establishes a real creative teamwork between illustrator and client or art director, and that sets the bar very high. It can escalate the art. When that happens, it’s a wonderful thing.

Sometimes, interruptions can be welcome, when I’m lost on the winding paths of production. Sometimes, there’s a difficult bit taking all of my attention, and I won’t even hear what people are saying two feet from my face. There’s no hard and fast rule. I’ve had to refuse work, even very good work, when I’m in certain phases. I always regret it later, when I’ve overcome the obstacle. I always need money. Always. More.

Can you share a few books that you find particularly inspiring? Books that have made a lasting impression on you over the years? Also, what kinds of books did you like to read as a child? Are there books from your childhood that have informed your life and work as an adult?

Oh, I should have made a list! There are so many, or so very few, depending on your point of view.

In short: Gary Panter’s series Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, shocked me completely. In every sense. Same thing for Mœbius’s Airtight Garage: before those books, I didn’t know that people could make and then publish things like that. Those are both masterpieces. Sadly, Mœbius’s book never got a nice hardcover release.

Two books by Richard McGuire stood out to my eyes and my mind: What's Wrong with This Book? and Popeye & Olive, for which I was extremely honored to be the editor. I unfortunately couldn’t edit it as well as I wanted to: the paper I chose had just ceased production.

One of Tomi Ungerer’s books: The Three Robbers. Found it in the school’s library-bus. Good God! The bad guys were the heroes! A beautiful book, beautiful drawings, a beautiful story. Wonderful author. A wonderful person.

The Blue Lotus, by Hergé. A perfect book. The old editions (black and white and color) are gorgeous. The modern ones have kept the story and drawings, but they don’t have the same charm. Too cold.

A series of very well done little books, published by someone who ended up becoming one of my best friends: Frédéric Debroutelles. Pascal Doury was one of the heroes!!!

Agony, by Mark Beyer. Also perfect. It’s in one of those formats that I loved when I was a child. His drawings can also evoke that creation. But then disillusion and horror follow, and it’s wonderful.

Land of 1000 Beers by David Sandlin: the woven quality, the sensuality of Ben-Day.

El Borbah, by Charles Burns. And he was never so close to the childlike fantasy as in those very adult stories. Those books were published in the same collection as Jimbo and were extraordinarily well done, despite their apparent simplicity.

A Passionate Journey, by Frans Masereel. No explanation needed. The narration! A small book that has stayed with me for a long time.

Face to Face by Jean and François Robert. Such clear form, such rigorous models serving such a simple but brilliant idea. Well produced.

Graph’zines, the pioneering work of some of the artists from an era that seems so long ago now. Some are as gorgeous as a firecracker.

Wir Junge Pioniere, by Keiti Ôta. A book as improbable as it is perfect. Der Polarforscher, by Henning Wagenbreth, is also a masterpiece. I still read both of them, and I always cry, they’re so good.

Popular pictures from around the world!

Etc. I can’t reasonably list everything, I’d have to show you my library, and I don’t own everything as it is.

Ballad and Vacation represent a deep commitment to narrative exploration and storytelling. What led you here from your work as a screen printer? How did you become obsessed by narrative and committed to playing with its form?

Same thing here. Nothing specific to add.

Did Miyazaki and Japanese aesthetics serve as an inspiration to Vacation?

Haha! I think Miyazaki is one of the greatest artists of our time. Unquestionably. There is great humanity in him and his works, and I admire him greatly.

But I don’t think that he influenced me directly for this book. My influence was a writer and poet: Kenji Miyazawa, who is a genius, and also, I believe, influenced Hayao Miyazaki.

Why Kenji Miyazawa? I stumbled upon a collection of his texts one day and I instantly found myself transported back to my childhood. I don’t know how the connection could have been made, but it was there. I wouldn’t be able to illustrate his stories, though, because my own memories are mixed inextricably in. The simplest thing would be to demolish and reconstruct the whole thing as best I could, to translate it into my own language—which I’d have to reinvent or rediscover... which is what I did with Vacation.

The trouble and magic of childhood are elements within almost all of Hayao Miyazaki’s films. But they are also my own elements. The true challenge of this book was expressing them as best as I could. I needed ample material, richly detailed, with enough depth for backgrounds, which could suggest a vaster world, both familiar and unknown. All these qualities are of course present in Miyazaki’s films, far beyond what I can do. Once again, it’s in the choice of what is not shown and in the expressions and silences of the book that is created by real space, the resonance chamber. It’s not at all the way things are expressed in films; it happens differently there. I am a director... of books! That’s all.

E.T.A. Hoffman was also another inspiration for this book, and another person who I wouldn’t be able to illustrate, and who tells me this: life only has one dimension. Bruno Schulz also whispers this to me... as does existence, always.

Do you have 5 favorite words in the French language? In German? In English?

No. I have a bit of a fetish for books, but not vocabulary. That doesn’t mean I don’t care, though. Every language has its own particular flavor.

If you had no restraints in terms of time and money, what would you do?

Nothing at all. I’d read, do some work around the house. Eat. Sleep. Watch life pass by. I already do all of that. I’d just be able to do it better.