A new video posted to social media last month shows the first combat footage of a drone dive bomber, dropping bombs into Russian trenches. Small First Person View (FPV) drones, originally developed for drone racing, have been extensively used in this conflict for kamikaze attacks, but this is the first time they have been seen dive bombing.

While this footage is unverified and unofficial—like most videos released during the Russo-Ukrainian War—we know that “FPV [dive] bomber drones are already widely used on the front lines,” a spokesman for the Ukrainian volunteer group Steel Hornets tells Popular Mechanics. The group, which mainly produces special munitions for drones, has released videos of dive bomber tests putting its weapons to use.

Greatly feared in WWII, dive bombing could make FPV drones vastly more dangerous.

Repeating History

Small drones in Ukraine have followed the same path as aviation in WWI, starting with unarmed scouts and progressing to improvised weapons, early dogfights, then purpose-built bombers, and now dive bombing to deliver ordnance accurately on targets.

Bombing in level flight is difficult due to the challenge of dropping the bomb at exactly the right moment. Releasing too early or too late, even by a fraction of a second, will result in under- or over-shooting. Even with the famous WWII Norden calculating bombsights—which supposedly enabled a bombardier to “drop a bomb into a pickle barrel” from high altitude—bombers could only achieve a “CEP” (Circular Error Probable) of 1,200 feet, meaning that half the bombs dropped landed in a circle of this size. Level bombing was too inaccurate to hit tactical targets like a pillbox or an artillery position, and could only be used for larger targets like factories or cities.

Dive bombing is simpler. The pilot lines up the aircraft’s nose with the target during a steep dive, then releases the bomb so it continues to the target while the aircraft peels away. All it takes is some judgement . . . and a lot of nerve.

It’s also far more accurate than level bombing. Skilled Junkers Ju-87 “Stuka” pilots could put their bombs in a 90-foot circle. Stukas scored numerous kills on tanks and other vehicles, even hitting moving targets. Dive bombers were an integral part of the German Blitzkrieg. Nicknamed “flying artillery,” they swept ahead of an armored advance to engage anything on the ground that might slow them down.

Dive bombing precision was assisted by a range of tools from markings on the cockpit canopy showing dive angle to sophisticated analog computers. The German BZA BombenZielAnlage, or Bomb Target System, assessed the angle of dive, speed, and altitude to help hit an exact spot on the ground.

British and American dive bombers were mainly used in naval war. The Douglas SBD dive bomber sank more Japanese ships than any other carrier-based aircraft. But dive bombing fell out of favor and the Stukas lost their sting due to one significant drawback: the technique is extremely dangerous to the pilot, as it exposes them to enemy fire at close range during the dive.

This vulnerability was the reason for the distinctive scream of a diving Stuka: it was a defensive measure, produced by sirens known as Jericho Trumpets, to terrify defenders into running or taking cover instead of firing back. The idea for these sirens is sometimes credited to Hitler himself.

Dive bombing worked well at the start of WWII, but became more hazardous with increasing numbers of anti-aircraft weapons. Air forces switched to less risky tactics, with both the U.S. and U.K. using rockets, which were less accurate than dive bombing, but did not expose the pilot to the same risks.

This Time, It’s Impersonal

Drone bombing in Ukraine is usually carried out by multicopters hovering several hundred feet above a target. At this altitude, they are often too high to see or hear, and much too high to hit, but bombing is inaccurate and it may take several attempts to hit a target in a vital spot.

In July 2022, Ukrainian forces started using improvised FPV kamikaze drones, racing quadcopters fitted with explosive warheads. The FPV drones are single use, but have the advantage of speed and precision, plus a hit rate of over 50 percent. They can strike moving targets and hit vehicles sheltering under bridges or in tunnels.

FPV drones lack the electronics to fly smoothly, avoid obstacles, and remain in a steady hover. This makes the kamikazes cheap, and means they can be easily assembled from commercial components for about $500. In addition, the powerful motors allow FPVs to carry a serious bomb load—perhaps twice as much as a standard quadcopter, enough to carry an effective anti-tank warhead.

The limitation of course is that kamikazes can only be used once, making them more expensive per strike. A reusable kamikaze would be better, and the dive bomber promises the speed, accuracy, and payload of a kamikaze with the low cost of a reusable drone.

The technique is the same as with traditional dive bombers. The drone lines up in a near-vertical dive, releasing the bomb load seconds before impact. Of course, this exposes the dive bombers to defensive fire, but the casualty rate will still be less than the 100 percent suffered by kamikazes.

But dive bombing is not as easy as just ramming a target. “Its use requires much better skills of the pilot, because diving is a very difficult maneuver,” a spokesman of Ukraine’s Escadrone volunteer drone-making unit tells Popular Mechanics.

Steel Hornets agrees. It takes considerable training to fly kamikaze attacks rather than a regular quadcopter, but dive bombing takes it up another notch.

“The main drawback is that the pilot must possess superior piloting skills compared to operating a kamikaze drone,” says the Steel Hornets spokesman.

First Live Action

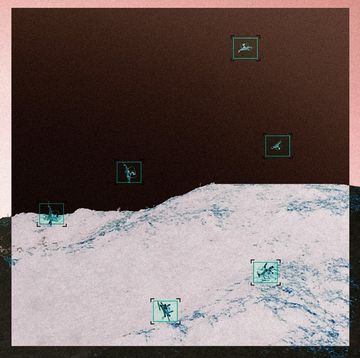

On May 17, Twitter user @Paul Jawan, a prolific source of Ukraine combat videos, posted footage with the title “One of the first sorties of the FPV unit of the tactical group Adam.”

The 96-second video shows four attack runs in which the drone flies over Russian positions, dropping what are described as thermobaric bombs. Previously, FPVs have been seen armed with Ukrainian-made RGT-27S2 thermobaric hand grenades. This munition weighs 21 ounces and produces a powerful blast, but no shrapnel. It’s not effective in the open, but lethal in closed spaces such as trenches; and in the second two strikes, the bomb appears to be dropped right inside Russian defensive works.

Tactical group Adam is a Special Forces unit that has fought in several major actions including the defense of Kyiv, the fighting around Mariupol, and the Kharkiv front. They are currently reported to be committed to the contest for Bakhmut. Special Forces have been among the early adopters of FPV drones, and it is not surprising that they should pioneer drone dive bombing.

Meanwhile, the Russians are also working on dive bomber drones. A video posted by Russian State media Ria Novosti in April shows troops carrying out trials with an FPV drone that releases an RPG anti-tank warhead in a steep dive. In two tests, it hits within a few yards of a target post, though of course misses might not be shown.

“The Russians are trying to speed up this kind of testing and evaluation to compete with Ukrainians,” Samuel Bendett, an expert on Russian drones and an adviser to the Center for Naval Analyses and Center for New American Society think tanks, tells Popular Mechanics. He notes also that the key for successfully executing these attacks is well-trained pilots.

Superiority via Software?

In the Adam video, an orange oval appears over each targeted area before it is hit. According to Erwin Foekema, an experienced FPV drone pilot, the ovals were likely added in post-production. He can tell because he is familiar with the FPV display shown, which comes from the open-source Betaflight software, and does not include dive bombing aids.

“The Ukrainians could make changes and add stuff themselves to the open-source project, but this is a huge and complicated task,” Foekema tells Popular Mechanics. It would make far more sense for them to develop their own dive-bombing system.

Steel Hornets also confirmed that bomb aiming is still carried out by eye. “Aiming is solely dependent on the pilot’s skills and experience,” the Steel Hornets spokesman says.

Ukraine already has a small fixed-wing drone, the Punisher, with automated software for accurate level bombing. Dive-bombing software should not be much harder. Software could perform the same function as the German WWII BZA analog computing, but of course the modern version would be far more capable and could be linked directly to the flight controller. This might change dive bombing from a skilled art to a matter of pointing and clicking at a target on the ground.

Ukraine is currently equipping 60 new drone assault companies. They are receiving a mix of types, including FPV attack drones, which could be adapted to dive bombing. Squadrons of drone dive bombers attacking simultaneously could have a devastating impact.

In 1918, German forces used “battle planes” to assault Allied trench lines. The dive bombers provided shock effect to make up for the German lack of tanks compared to the Allies. In 2023, Ukraine, which also lacks a large tank force, may use dive-bombing battle drones against Russian defensive lines for the same reason. As with WWI, we appear to be poised on the brink of a new era of air power. And once again, nobody knows exactly how it will play out.