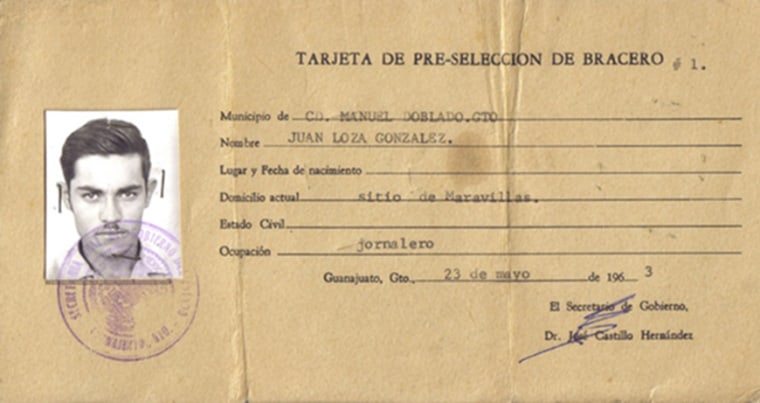

Juan Loza was watching the news over the weekend at his home in Chicago when he saw the unthinkable. A statue honoring his contributions was being unveiled before his eyes.

Two thousands miles away, in downtown Los Angeles, the nearly 20-feet-tall statue shows a Mexican farmworker standing in the middle of the newly inaugurated Migrant’s Bend Plaza, celebrating the legacy of millions of Mexican nationals, who like Loza, came to the United States to work under the Bracero Program, which was created to deal with labor shortages from World War II.

"It immediately struck a chord with me," said Loza, 79, who participated in the program during the early 1960s. "It was an unforgettable experience," he told NBC News in his native Spanish.

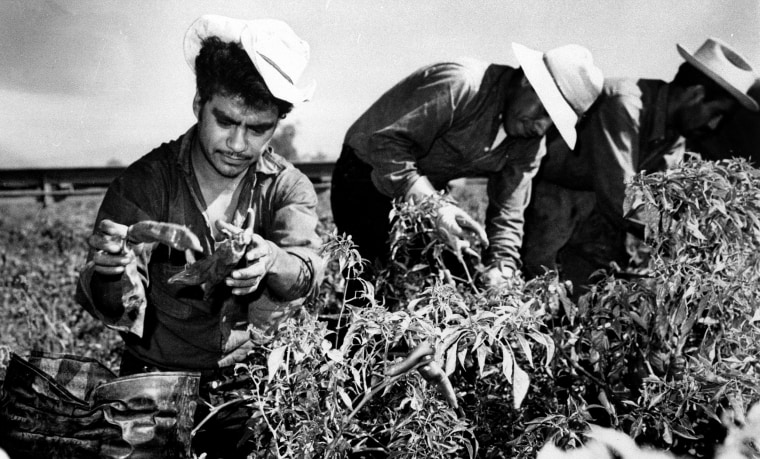

Though the program marked a crucial moment in the nation's immigrant and labor history, many Americans are not familiar with the history of the largest guest worker program in the Americas. The program, which gave out 4.6 million short-term labor contracts to Mexican workers, lasted 22 years, from 1942 to 1964.

For many Mexican Americans who can tie their heritage to the braceros, this history is a point of pride because "many of us can say that our family contributed to this country" and it "challenges the narrative that we came here without being wanted," Mireya Loza, a Bracero Program scholar and Juan Loza's niece, told NBC News.

"I didn't only help me and my family, but I helped this country when they were in need," Juan Loza said. "Thanks to God, this country received me with open arms — even if the current political narrative tries to ridicule us and tries to say the opposite, which we all know is a lie."

Artist Dan Medina's bracero statue portrays a man holding a hoe, a field work tool known as “el cortito.” Standing next to him is his wife holding their son, who is shown clutching a toy Ford truck in one arm while reaching for his father with the other. To their right lies a pile of workers’ tools and other symbols depicting the work of these Mexican migrants.

Mireya Loza is a professor at New York University who worked on the Bracero History Archive and wrote the book "Defiant Braceros." She said that a particular source of pride is the fact that "a temporary work program that was not designed to create permanent Mexican American communities created exactly that, and even a permanent statue honoring that legacy."

Many braceros ended up staying in the U.S., some applying to remain through legal means and others just staying.

Los Angeles City Councilman Jose Huizar, whose father and 10 uncles came to the U.S. through the program, dedicated the new monument to all immigrants and to their contributions to the nation.

"Braceros played an important role in the economic success of this country during World War II and after, but they have long been overlooked," he said in a Facebook post Monday. "In truth, their social and cultural impact was profound. I am proud that this monument will help tell their story, and I thank them for their contributions."

The program was controversial, according to the Bracero History Archive, since it fueled concerns among U.S. farmworkers that braceros would compete for jobs through lower wages. Employers were supposed to hire braceros only in areas with certified domestic labor shortages and were not supposed to use them to brake farmworkers' strikes. But many of these rules were ignored in practice, according to the archive.

Farm wages dropped sharply from the 1940s to the mid-1950s, in part due to the use of braceros and undocumented laborers who lacked full rights in American society, according to the Bracero History Archive.

Even after documented human rights violations stemming from the program, the U.S. created other forms of legal immigration such as the H-2A visa program to allow foreign nationals into the U.S. for temporary agricultural work, Mireya Loza said.

Juan Loza remembers seeing other braceros injured, missing an eye, a leg or an arm, and wishing he could do the work for them, so they could rest. He said he has talked to his children and grandchildren about his time as a bracero.

"By telling them my story, I hoped that they would feel proud of who they are and where they come from, even if other people tried to bring them down or tell them that they weren't enough," he said.

Loza said he hoped his efforts to pass down his stories as well as initiatives such as his niece's Bracero History Archive and historical monuments can help preserve a legacy future generations should feel proud of.

His niece agrees.

"Public monuments do a lot for the interpretation of the past," Mireya Loza said. "Now, you will have more teachers, more children, more people asking about this unavoidable part of history every time they see that bracero statue."

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.