The ancient—and mysterious—history of ‘abracadabra’

The earliest mention comes from a text in the second century A.D., which used the term as a treatment for fevers.

When you hear the word “abracadabra” you know that something magical is meant to have happened—a transformation maybe, or at least just a trick. The word itself is peculiar, yet it’s now an almost universal signal of the supposedly impossible. And while experts debate the exact origins of abracadabra, the word is undeniably ancient.

Abracadabra first appears in the writings of Quintus Serenus Sammonicus more than 1,800 years ago as a magical remedy for fever, a potentially fatal development in an age before antibiotics and a symptom of malaria. He was a tutor to the children who became the Romam emperors Geta and Caracalla, and his privileged position in a wealthy noble family added importance to his words.

Writing in in the second century A.D. in a book called Liber Medicinalis (“Book of Medicine”) Serenus advised making an amulet containing parchment inscribed with the magical word, to be hung around the neck of a sufferer. He prescribed that the word be written on subsequent lines, but in a downwards-pointing triangle with one less letter each time:

ABRACADABRA

ABRACADABR

ABRACADAB

…

AB

A

The inscription would then consist of 11 lines, written until there were no characters left in the word; and in the same way, Serenus said, the fever would also disappear.

A word against evil spirits

According to recent research, versions of abracadabra also appear in an Egyptian papyrus written in Greek from the third century A.D., which omits the vowels at the start and end of abracadabra in subsequent lines; and in a Coptic codex from the sixth century, which uses the same method but a different magical word.

For followers of Greek magic, writing variations of a word in a downwards-pointing triangle formed a “grape-cluster” or “heart shape,” which was a way of writing down an oral incantation that repeated and diminished the name of an evil spirit in the same way. Such spirits were thought to cause diseases, and both these versions of the abracadabra spell were supposed to cure fevers and other ailments.

Abracadabra was an “apotropaic—a word that could avert bad things,” explains Elyse Graham, a historian of language at Stony Brook University, noting that its origins have been much debated.

Some think abracadabra comes from the Hebrew phrase “ebrah k’dabri,” and means “I create as I speak,’” while others think it comes from “avra gavra,” an Aramaic phrase meaning “I will create man” — the words of God on the sixth day of creation. Still others note its similarity to “avada kedavra’, the “Killing Curse” in the Harry Potter books, which author J.K Rowling has said is Aramaic for “let the thing be destroyed.”

Medieval historian Don Skemer, a specialist in magic and former curator of manuscripts at Princeton University, suggests abracadabra could derive from the Hebrew phrase “ha brachah dabarah,” which means “name of the blessed” and was regarded as a magical name.

“I think this explanation is plausible because divine names are important sources of supernatural power to protect and heal, as we see in ancient, medieval, and modern magic,” he says; for early Christians “names derived from Hebrew enjoyed high standing because Hebrew was the language of God and Creation,” Skemer adds.

A spoken remedy

Abracadabra seems to have kept its function as a magical cure against illness for many centuries. A 16th century Jewish manuscript from Italy records a version of the abracadabra spell for an amulet to prevent fever; and the English writer Daniel Defoe noted in A Journal of the Plague Year that it was used in 17th century London to prevent the infection: “as if the plague was not the hand of God, but a kind of possession of an evil spirit, and that it was to be kept off with crossings, signs of the zodiac, papers tied up with so many knots, and certain words or figures written on them, as particularly the word Abracadabra, formed in triangle or pyramid.”

But the word seems to have lost its usefulness as a remedy, and in the early 1800s it appeared in a stage play written by William Thomas Moncrieff, as an example of a word magicians would utter. Its only notable reference in the 20th century may be in the Thelema religion founded in the early 1900s by Aleister Crowley. The occultist often used the word “abrahadabra” in his 1904 Liber Al Vel Legis (“Book of the Law,”) saying it was the name of a new age of humanity; and he claimed to have derived it from the numerology system known as Hermetic Qabalah, which induced him to swap out the C of abracadabra for an H.

Descent into conjuring

Historian Graham notes that magic was thought useful as a remedy only before modern medical developments: “We used to need magic to do different things, but we have better medicines now,” she says. And that’s relegated abracadabra to the realm of stage magic and conjuring tricks: “Now magic is more about spectacle and distraction.”

If abracadabra still retains any power, it may be because no one is sure what it means. “A magic word gives power to the magician, while outsiders don’t know what it is,” Graham says. “It endows the magician with power in the eyes of other people.” So if abracadabra sounds nonsensical, maybe that’s the point, she says: “If the word weren’t mysterious, then it would be less magical.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

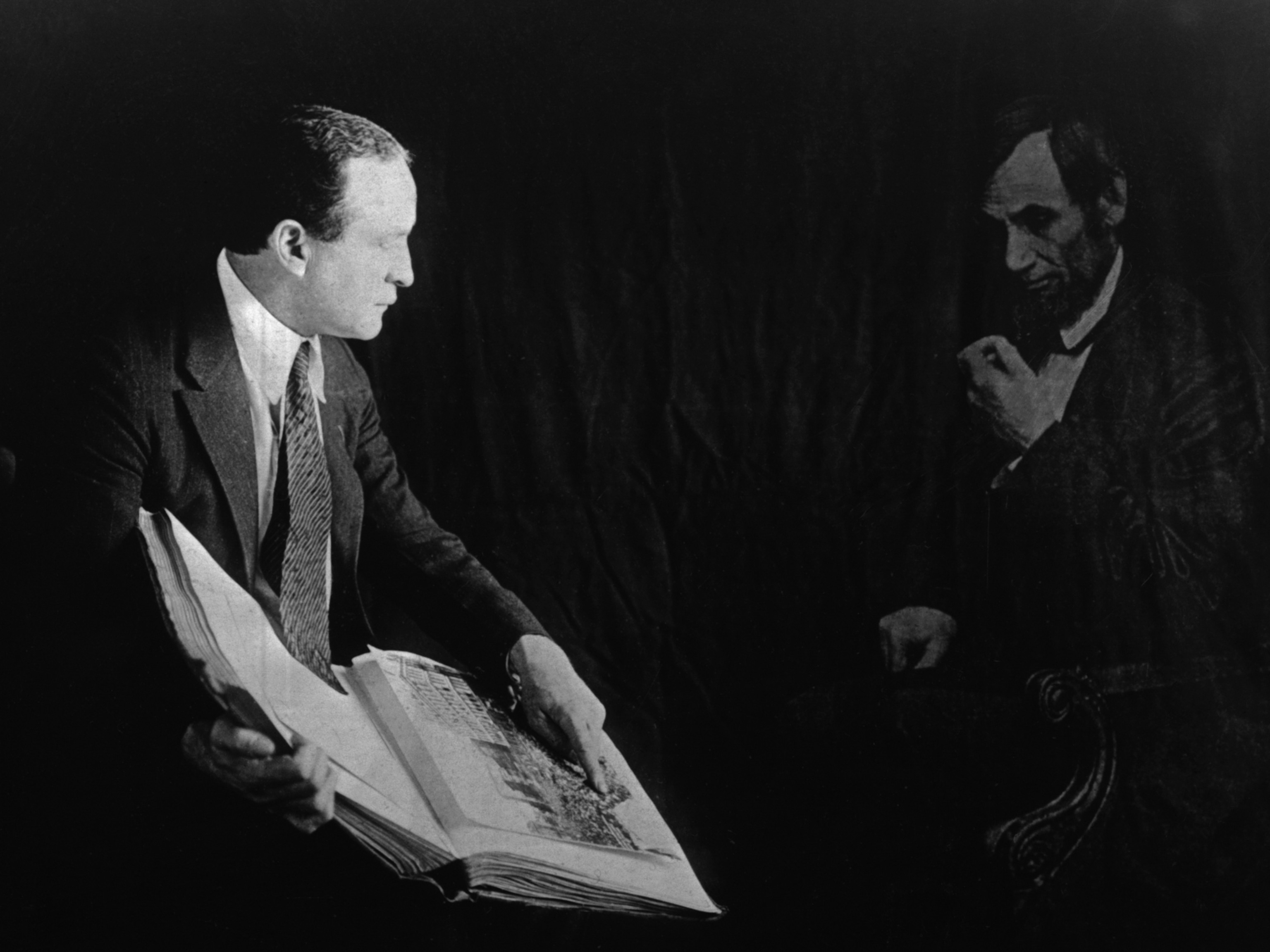

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursDina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?