This year’s Game Developers Conference is just around the corner, and I’m very excited to make the trek to San Francisco once again. This will be my fifth GDC (I attended in 2013, 2014, 2019 and 2021), and I thought it would be a good opportunity to reminisce about my own relationship with video games, and what made this art form take such a special place in my life.

Paris, Late 1980s

Although I had been thinking of writing music for movies since I was 12 years old, I didn’t start a cinephile. My parents did not go to the movies, and we didn’t have a TV at home; this explains why my love for cinema only really started when I was of age to go to the theaters on my own. In fact—and contrary to what happened to most kids in the 80s—the ‘entertainment’ I experienced then mostly took the form of video games: I was seven years old when my dad brought home our first computer, and with it came the beginning of my life as gamer.

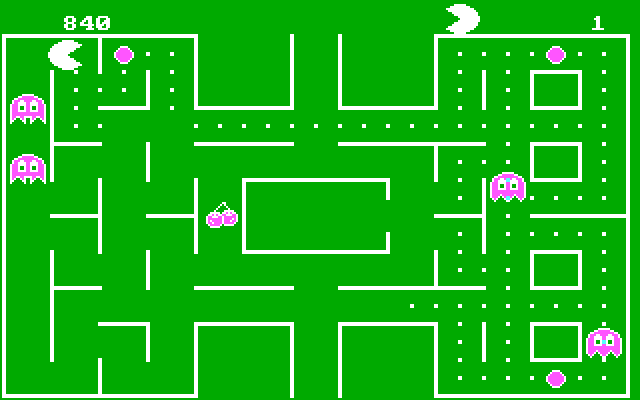

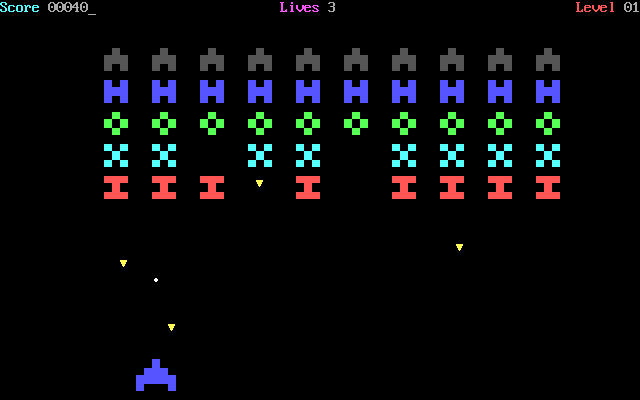

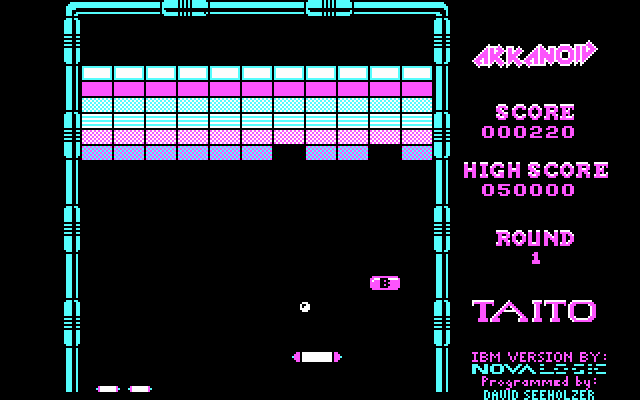

My dad’s computer was an IBM PS/2 286, running MS-DOS, and it was special in the way that it wasn’t really that special: at the time, the only two personal computers my 7th-grade classmates had mentioned were the Macintosh and the Commodore 64. (In hindsight, my dad had made the right bet.) But it was on that computer that I played my very first video games—staples such as Tetris, Packman (a shameless Pac-Man clone for IBM PCs), Space Invaders, and Arkanoid.

Tetris

Packman

Space Invaders

Arkanoid

But the games that marked me the most back then all featured one specific element that, 35 years later, I’m still able to remember exactly as it was: the music. The most famous of all of these games was—no question—Prince of Persia. But to this day I can also still sing The Adventures of Captain Comic’s US Marine Corps Hymn-inspired tune (as well as its following sound effects) and Grand Prix Circuit’s groovy dance-like theme (the only thing it’s missing is a drum beat!).

The truly wonderful thing at the time—and this was completely lost to the 7-8 year old me—was how utterly amazing the music sounded even though it all came from a scrappy PC Speaker. Working with very limited technical specs, the programmers at the time had figured out a way to make this terrible piece of audio equipment sing memorable tunes with polyphonic harmonies and melodies, arpeggios, and beats. Tunes so insanely good that I can still sing them today!

And while I was lucky enough to discover other games with memorable music at the time (such as Tetris and Super Mario Land on my best friend’s GameBoy), it really was the PC that started it all for me. It sounded basic, raw, pure. I was hooked.

Exploring a Brand New World (The Early 1990s)

In 1991, the world of video games fully opened up to me when my older brother bought his own rig: an IBM PC compatible computer with an Intel i386DX 33 Mhz processor. It was a much faster computer than my dad’s, with a bigger and better display, and (most importantly) it could run the latest, greatest games. But what made its impact even more critical was the fact that it sported an internal card that, for me and so many others, changed computer gaming forever: a Creative Labs Sound Blaster Pro.

Thanks to the Sound Blaster, games now could play back all kinds of music that, as a classically-trained musician, I had never really heard before. Not only that, I also quite suddenly realized that games could tell you a story—a story that you were actively engaged in—and as you went along the game and its story, it would play music specifically tailored to that point.

There was, of course, the title music. Then, often, a music for the game’s menu. Sometimes, the music played during the whole game—and sometimes just cutscenes, or some other really important moments, like… when you died. The variety of experiences made this world feel not only expansive and limitless, it also made it fun and exciting to explore. Everything felt new, everything felt surprising. At a minimum, it felt to me like each game had its own concept, its own controls, its own story, its own look, and, more critically, its own aural soundscape.

Like in a movie: Origin’s Wing Commander.

“In the beginning”… A mysterious introduction for Sid Meier’s Civilization.

Spooky background music for the starting menus in Eye of the Beholder.

Take The Secret of Monkey Island, for example. Who could not feel transported to a remote Caribbean island as soon as the main title started playing over the night skies of Melee Island? This sounded fun! And who could not immediately fall in love with all the little Lemmings falling down the cave as soon as you heard their music play? This sounded cute! And who could not feel the fear running down their spine as they started an Alien Terror mission in X-COM: UFO Defense and the only thing being heard was the game’s sparse, slow, and creepy music? This sounded terrifying!

Thanks to the Sound Blaster Pro, and the power and flexibility of MIDI rendering, music now allowed for a breath of styles and instrumentations that seemed infinite. Of course, as someone raised on listening to classical music, I first expected games to rely on traditional instruments for their music: orchestral (Wing Commander or Little Big Adventure come to mind), jazzy (Transport Tycoon), or traditional/folkish (Ultima VII).

But other games fully embraced their technological and futuristic settings: Cryo Interactive’s oft-forgotten space opera game Dune was punctuated by an incredible new age-y score (written by French composer Stéphane Picq); Bullfrog’s techno-punk game Syndicate and LookingGlass’ first System Shock were accompanied by a fitting synthesizer-heavy soundtrack; and Origin’s Crusader: No Remorse featured a non-stop, bombastic, full on electronica techno-y type of score. (As an aside, later discovering Necros’ music and the .MOD tracker music format was a revelation for me).

Welcome To The CD-ROM Revolution (The Mid-1990s)

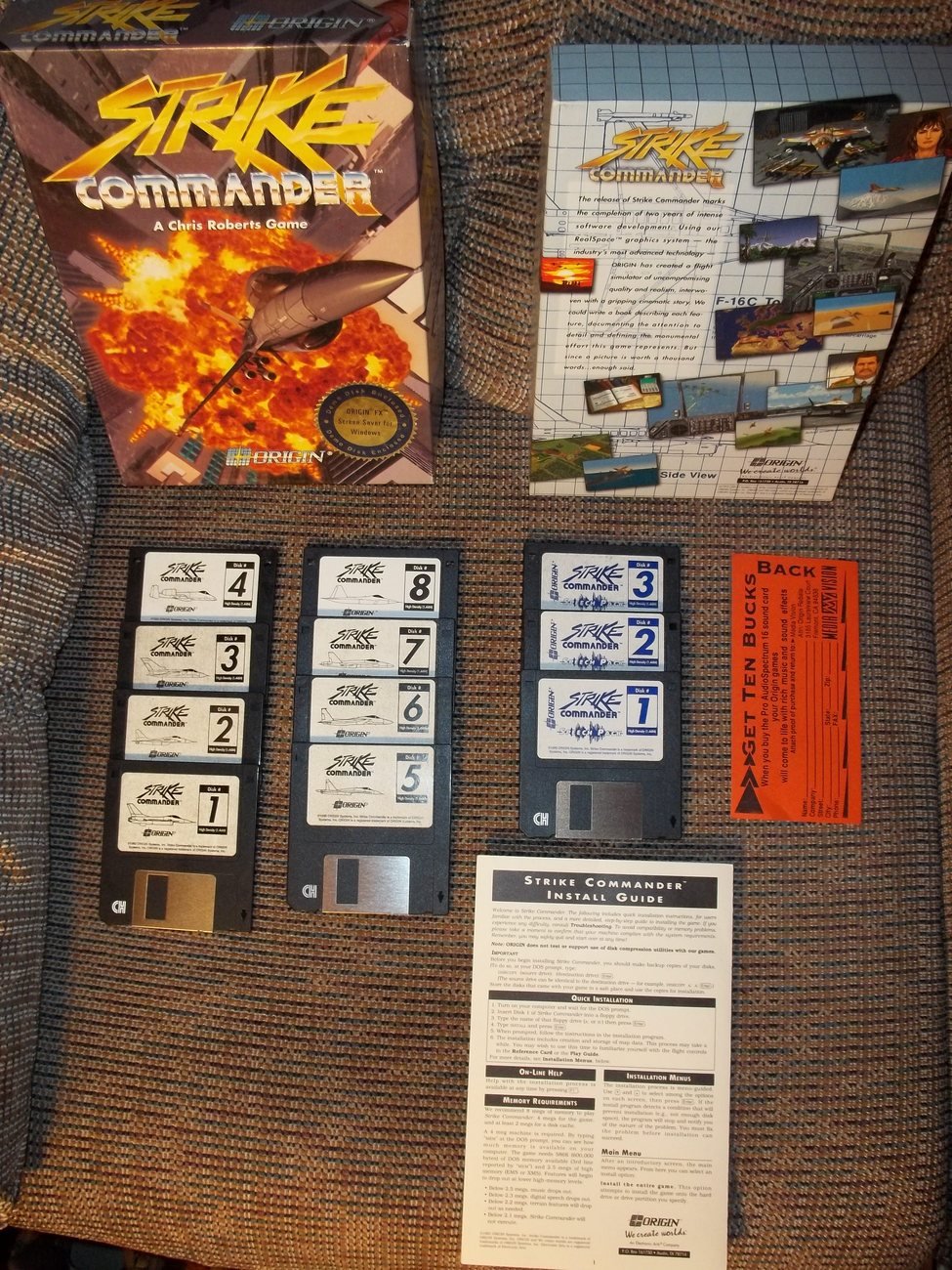

Video game music took, of course, a massive leap when CD-ROM players went mass-market and games started shipping on that format. Gone were the days of swapping dozens of 3.5” floppy disks into your computer to play a game (I’m looking at you, Strike Commander), and so gone were the days when developers had to constantly fight against very limited storage space. This in turn meant that composers would not have to limit themselves anymore to the spotty MIDI restitution that the gamer’s system sound card would allow. Interestingly enough, the narrative and stylistic trends established during the early 1990s didn’t evolve much over that time—but the quality just went up significantly and the music became thus way more effective in its mission to further enhance the gamer’s involvement in the game.

We suddenly went from this…

… to this.

Even before soundtracks would start being recorded live, the CD-ROM, with it vastly superior storage space, allowed music files to be delivered fully rendered. Consequently, controlling the final render meant that it was now worth it for composers to spend more time on how good their music sounded. In parallel, samplers became much more capable on the composer’s end, so all genres suddenly sounded better than ever: orchestral (Warcraft II, Baldur’s Gate, Total Annihilation), hybrid (Command & Conquer), New Age (Lost Eden), rock-and-roll (Duke Nukem 3D), electronic (System Shock 2), traditional/folk (Ultima Online), and even light jazz (Theme Hospital).

Additionally, the music was now much more “adaptive” than it had ever been. Because developers suddenly had more space available at their disposal, it was now possible to have even more music specifically tailored to what happened on screen. In Ultima Online and Baldur’s Gate, for example, the music changed seamlessly as you would approach a town (with some villages having their own musical themes), entered a dark forest, or started fighting against dangerous beasts. In System Shock 2, the music was spotted so that it would have a very specific narrative use, including the developer purposely selecting moments without any score at all. The music would then come in to set a creepy atmosphere, enhance the tension, prop up the adrenaline… and then once an important moment ended, it would somehow disappear into nothingness, leaving in its place a suffocating silence as you wandered around the empty corridors of the Von Braun starship.

Aside from its intro music, System Shock 2 has no score at all in the first 13 minutes of gameplay—until the player kills their first enemy. This type of sparse “spotting” tremendously increases the impact of every piece of music in the game, on both narrative and emotional levels.

Around the end of the 1990s, video game soundtrack albums suddenly started appearing. As the market for video games exploded, and as the cost of duplicating CDs decreased, more and more publishers opted to release their game’s score, either commercially or as promos. Although film soundtracks had been made available for decades (going back to the vinyl days), this was a completely new trend, further demonstrating that game music was becoming mature enough (both in quality and in running time) to stand on its own and justify a listening experience outside of its intended purpose. I still remember scavenging my favorite record store for game soundtracks, and feeling like I had won the lottery when I found Joel McNeely’s Star Wars: Shadow of the Empire or Michael Giacchino’s Jurassic Park: The Lost World.

Adulthood and Early Career Considerations (The 2000s)

As I made my way into adulthood and started attending Berklee College of Music, my relationship with gaming cooled down somewhat. Because of my studies, and my burgeoning career in Los Angeles, cinema and film music became much more of a focus. Instead of trying every single new game, like I had done as a teenager, I turned more selective in the games I played. Yet games like Deux Ex, Warcraft III, Civilization IV, or BioShock all had a common thread: they all featured incredible soundtracks, used in ever new and innovative ways.

After a few years of working as a composer’s assistant, I started pushing my solo career as a composer and I looked back at the art forms that inspired me in my formative years—as a kid, a teenager, and a young adult. While movies were high up, video games were higher still. This is why, in 2013, I decided to attend my first GDC: to explore how my skills could be of use in the industry that had provided me so much joy over the previous two decades. Amazingly, work would soon follow that year in the shape of the serious game Time Explorer, which I scored for Studio Cegos. And the following year, I wrote the music for my first casual game, MagiWords (I also created the game’s sound effects).

It’s also at GDC that I met with incredible composer Christopher Tin, who became a great friend, and who asked me in 2016 to orchestrate some of his music for Civilization VI. Working on my favorite game franchise of all time, which I started playing more than thirty years earlier, was a seminal moment in my career and in my life; simply put, I felt like I had gone full circle.

And finally, a few more years later, I got called to score three battle stages in Bandai Namco’s Jump Force: Hidden Leaf Village, Planet Namek, and Los Angeles. It’s at that point that I realized I had achieved something I had been secretly dreaming of since I was a little kid, all the way back to my days playing Prince of Persia and Grand Prix Circuit: writing music for video games.

Jump Force: “Hidden Leaf” Stage

Jump Force: “Planet Namek” Stage

Jump Force: “Los Angeles” Stage

So, what made the music from these games stick for all these years? In hindsight, I’d say, melody—as always, that’s the high-order bit. And I strongly believe it always will be. The fact that a casual listener can whistle a tune 35 years later is, it must be reminded, quite an achievement on the composer part!

But I think what the games I picked from the 1990s also show is that the most important part of a good music is how well it fits the story. After all, all these games are trying to do is achieve suspension of disbelief for as long as possible. The developers want you to believe—to feel—that you are alone in a space station trying to find out what happened to you. They want you to believe that you are fighting an invading alien force in the middle of nowhere, that you are flying over a sand planet, that you are commanding a massive army, or that you are having a restful drink in an old tavern.

Storytelling has always been a part of humanity. And over the ages, new ways of telling stories have emerged—sometimes by chance. Cinema, for example, wasn’t created to tell stories at first, but quickly the invention proved perfect to the task. Video games didn’t arise from a need to tell stories either—rather, their first goal was quick amusement—but within ten to fifteen years the storytelling capabilities of the medium seemed infinite.

Music, for its part, has always been an important and critical force in supporting how stories are told to people. Looking back to human history, the development and maturing of how music is used in games can thus been seen as quite logical—predictable, even. Yet it’s been truly magical for me to witness that development first-hand, during what I would call the most consequential decade in the evolution of gaming.

What about you? When did you first notice music in games you were playing? Is there a game that marked you forever because of its music? If so, which one? Did it play on a PC speaker, a MIDI sound card or from a CD? Let me know in the comments!