Theo Jansen

Empathic Systems

14.06.2019 — 08.09.2019

Kindly supported by: Mondriaan Fund, Königreich der Niederlande, Audemars Piguet

The Frankfurter Kunstverein has invited Yves Netzhammer, Theo Jansen, and Takayuki Todo to present a selection of their works in solo shows, under the shared thematic title “Empathic Systems.”

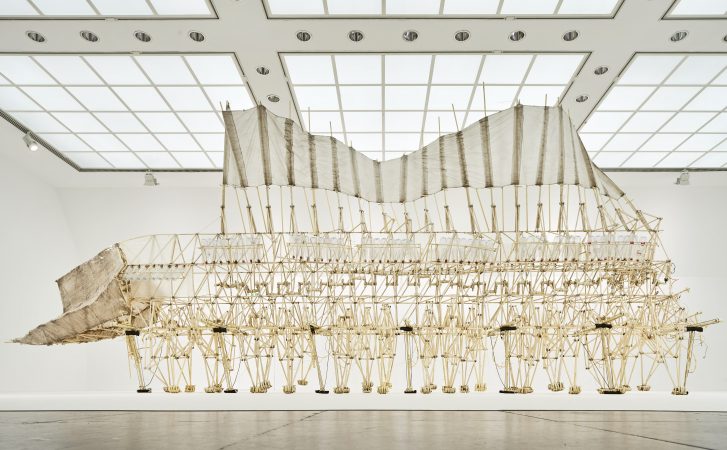

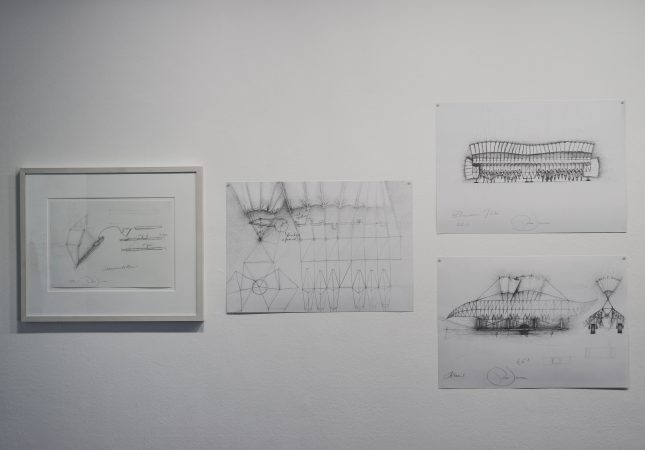

With his kinetic sculptures, Theo Jansen pursues his vision of creating new artificial life forms. The exhibition at the Frankfurter Kunstverein presents two of his creatures, the so-called “Strandbeests”, “Umerus” and “Ordis”. Drawings and technical sketches visualize the mathematical equations that the machines’ movement mechanisms are based on.

Jansen has succeeded in bringing non-biological creatures made from industrial materials to life that evoke the impression of living beings for the viewer. It is their movements that elicit an emotional reaction in the viewer and serve to amaze them. The uniqueness of the forms lies in the fact they develop independent movement from wind power alone. Jansen calls his constructions “Strandbeests” because he creates them for the specific environmental conditions of a beach. Jansen continually creates these constructions with ever developing capabilities. He labels each form as a separate genus, giving them Latin names in the style of a scientific approach. “Ordis” is derived from the conjugated Latin verb “you begin,” and “Umerus” from the noun for shoulder.

Theo Jansen’s exhibition is presented on the upper floor of the Frankfurter Kunstverein. One of his largest kinetic sculptures, “Umerus” (12 x 2 x 4 meters), is in the great hall. “Umerus” will be periodically animated by compressors. In the other space Jansen is showing the sculpture “Ordis” (2 x 2.30 x 1.70 meters), which visitors can move with their own strength, offering a physical experience. Drawings and technical sketches complete the presentation by visualizing mathematical equations that describe the workings of the machines.

Theo Jansen studied applied physics at the Technical University in Delft. He has been creating his works in the context of artistic practice since the 1990s.

The origins of Jansen’s “Strandbeests” come from a computer program that he developed in 1991. This system is applied to all his works so the Jansen movement principle has become internationally renowned. In 2016, NASA invited Theo Jansen to participate in a think tank to develop potential projects for autonomous engines that could be deployed in future space missions to Venus. Jansen has a worldwide community of admirers who use the unique mechanisms of his works as a starting point for the further development of fundamental ideas and forms in the fields of science and art.

Jansen uses yellow plastic tubes, cable ties, and plastic bottles as raw materials in his work. Each “leg” has a crank system with 11 tube parts. The tubes are perfectly coordinated so that the creatures’ movements glide along a horizontal line. By storing wind, the kinetic structures can even move without an external energy source for a short period of time. Wings pump air into empty PET bottles that serve as the creatures’ body parts. The proportions of the tubes are pivotal for the motion sequence. The creatures’ so-called “brain” consists of a step counter based on a binary system that allows the sculptures to interpret and respond to their environment like primitive creatures. “Umerus’” system is based on a series of empty bottles filled with air. When the creature enters the water, the bottles fill up with liquid instead, changing the function of the binary system and reversing the running of the machine. This is how “Umerus” perceives its location in the world; it locates itself in a certain position and derives an idea of where the danger of the surrounding sea is, as well as the remaining landscape. In a general sense, one could speculatively ask whether the machine produces its own—albeit simple—conception of the world.

Jansen has continuously developed his “Strandbeests” over the years. In a few years, according to Jansen’s vision, they should be able to exist in nature both independently and in groups. Although they do not have any metabolic processes, nor do they reproduce autonomously, in their ability to move and react to environmental conditions Jansen sees the basic characteristics of artificial life, which he continues to develop.

His creatures’ movements usually trigger a fascination in the viewer based on the idiosyncratic nature of their complex movement patterns, which appear organic and reminiscent of living beings. The structures are clearly recognizable as artificial, yet they evoke the organic walk and motor skills of long-legged insects, or caterpillars in the case of some creatures not shown.

Jansen’s creatures are reminiscent of archaic skeletons that dwell aesthetically somewhere between biomorphic and inorganic growth forms. Although Jansen’s constructions are obviously lacking intellect and free will, and he clearly remains the human author, their autonomous motion processes make one forget this. Movement becomes the characteristic trait of the living. At the same time, the viewer develops the assumption—through emotions and cognitive knowledge—that motor skills are the attribute of a living being.

In their uniqueness the creatures stand as novel aesthetic forms. The power of Jansen’s work is that they are free of any function; their actions are unintentional. They repeat the unchanging action of progressing in space and time, of walking on, drawing their power from the wind alone. They are independent of the metabolism of a living body and independent of the energy supply of a machine. They are creatures of their own form. What fascinates viewers is that they act without an awareness of the principals of their own mortality. They exist and do not fear their own decay. They follow their inner program and purpose without understanding these as fate. It is the viewer who can recognize something in their form that the creature does not posess itself. Their physique and their physical nature have been created by Jansen in such a way that their effect on the viewer unfolds on several levels simultaneously: the cognitive and the emotional.

About the exhibition “Empathic Systems”

The Frankfurter Kunstverein has invited Yves Netzhammer, Theo Jansen, and Takayuki Todo to present a selection of their works in solo shows, under the shared thematic title “Empathic Systems.”

The works of the three artists use varying aesthetics and result from completely different artistic processes. Nonetheless, all the works share a corporeal appearance despite being synthetically made. They are capable of touching the viewer solely through the form of their physical activity in space, beyond any recognizable linguistic conceptualization.

The exhibition revolves around the complex emotional relationship between humans and technology. Communication processes no longer only happen from human to human, but between humans and technology. Digital technologies are also increasingly exchanging data solely between each other.

Yves Netzhammer’s artistic oeuvre offers an examination of the central issues of being human in the digital age. His humanoid figures are reminiscent of anatomical puppets, devoid of any individual traits or facial expressions. Through them, Netzhammer formulates metaphors that translate the spectrum of human emotions into images. In a sequence of gestures and moments, he creates moods that the viewer knows how to decode, should they be willing to empathize and feel on behalf of the figures. Netzhammer’s figures define themselves through interaction with their environment. The reduced arrangements result in dense scenes where individual interaction processes take place that act as syntheses of human action and feeling. He extracts the essence of human experience and uses digital drawing and programming techniques to create animations that evoke empathetic reactions in the viewer. Netzhammer occupies three floors of the Frankfurter Kunstverein with a selection of his digital animated films, graphic works, and new kinetic installations.

Theo Jansen creates expansive kinetic sculptures and describes them as a new form of non-biological life. He builds the sculptures from synthetic materials such as polyurethane tubes, cable ties, and plastic bottles. The creatures he constructs are then are set in motion by wind, building up kinetic energy to start moving. Via a computer program that Jansen developed, an algorithm calculates the mechanics of the walking apparatus. The supporting skeleton is constructed in precise proportions. This creates flowing, insect-like movements that have an immediate effect on the viewer. The empathic relation to the creatures is not established by their face, anthropomorphic traits, or an expression, but rather their movements in space.

With his work “SEER,” Takayuki Todo explores the emotional effect of eye contact and facial expressions in the interaction between humans and technology. Using 3D printing modules, miniature motors, and facial recognition software, Todo has created an anthropomorphic head that seeks the viewer’s gaze, reciprocates it, and mirrors their facial expression. The minimal movements create an immediate synchronization of the gestures and facial expressions between human and humanoid, as well as an emotional reaction in the viewer. An asymmetry in the interaction emerges. For the viewer, the machine’s behavior seems like an expression of emotions. What the technical body accomplishes is the deconstruction and reproduction of the human gaze and the movements of the face’s surface. Though the viewer projects human intentions onto the machine, they are essentially looking at a reflection of themselves.

All three artists work at the intersection of engineering and computer science with psychology, cognitive science, neuroscience, and ethics. They bring together a variety of technical, artistic, and psychological principles. The works elicit a level of feeling in the human viewer that is not always linguistically graspable, but instead appeals to an empathic sensitivity. In a number of ways, their artificial apparatuses become mirrors viewers encounter and recognize themselves in: sometimes in their doubling, sometimes in their distortion.

Humans and machines differ substantially in the sensory apparatuses they use to perceive and understand the world. Recognizing things begins by grasping them sensorially. Humans experience and understand the world through their body and their sense organs. In doing so they create their interpretation of the world in the form of cognizance. The body is the medium for human being-in-the-world. It acts as the link between humans and the world, or between subject and object. It belongs to the ego and the world at the same time, it is subject and object in one. Technology does not have this corporeality.

Today’s state-of-the-art computer science has produced programs and algorithms that generate machine-specific knowledge through data sets and associated information. The ways that humans and machines generate knowledge and their consequent actions are still different. But the questions remains whether this gap narrow in the future.

Although there is neither a unified theory of emotions in the natural and behavioral sciences nor a definition that is accepted across the disciplines, interdisciplinary research projects are investigating different methods of increasing the human emotional response to digital agents under the heading of “Affective Computing.” Numerous industrial sectors have a great interest in recognizing emotional systems in order to use them for the development of machine learning and artificial intelligence. Functions should sound and look “more human,” thus minimizing the difference between human feeling towards technology as opposed to other humans.

For the most part, human beings can only recognize emotional signals and signs on the basis of physical characteristics. As such researchers are working to ensure that speech interfaces, talking robots, or humanoid nursing assistants, for example, are designed accordingly. Interfaces are being developed that implement knowledge about the meaning of emotional states and moods.

Research into emotions is thus gaining an increasingly central role in the research and development of artificial intelligence. Technologies are being used that examine users’ moods and their emotional reactions to content. Systematized knowledge about feelings, emotions, sensations, as well as moods, perspectives, and intentions is already being implemented in a targeted manner. So-called “online sentiment analysis” is being conducted, namely algorithmic tests that classify all content according to whether it was created with a subliminal positive or negative sentiment. Each author’s content and attitudes are evaluated. Political entities and commercial enterprises benefit from in-depth knowledge about the emotional responses of an individual, who is always also a user, consumer, patient, citizen, and thus part of an overall social system. Digital assistants and systems are undergoing further development to the point their speech recognition not only understands what a human is saying, but also the emotional state they are in as they do so.

The question concerning the meaning of emotions and the gaze of the other is one of the eternal human issues that have played a central role in all of cultural history. The exhibitions at the Frankfurter Kunstverein seek to show and reflect the connection between contemporary art production and current social phenomena. The perspectives of the interdisciplinary research field of Affective Computing will have an impact on a wide-ranging social and political scale.

The exhibitions devoted to Yves Netzhammer, Theo Jansen, and Takayuki Todo offer a concentrated view of each of their artistic worlds and aesthetic formulations. The exhibitions function through spatial experiences in which viewers encounter the works physically and sensually.

Netzhammer’s works beguile visitors with their intense visual and acoustic power. Todo’s SEER requires the visitor to actively interact with the robot, stepping directly in front of it to establish an emotional connection through eye contact. Theo Jansen’s kinetic sculptures are animal creatures that visitors can set in motion with their own physical strength in a sandy landscape.

Art has the ability to make people pause, perhaps halt time for a moment, forget for a moment, and to marvel. In amazement there lies an existential force, a yearning for deeper knowledge, for an understanding of the inner workings, for what “it” is and how to grasp it. The artistic view of the world is restless, questioning, searching, and striving for forms of representability. It employs for metaphor in the search for knowledge. Those who follow this view can succeed in experiencing something new through feeling empathy with others and re-experiencing themselves in this realm. In this encounter, art can become a transformative force.

Curator: Franziska Nori