The obituaries will describe Thomas Sean Connery as the actor who was made famous by James Bond. The jobbing manual labourer, lifeguard, life model, underwear model, milkman and, most famously, coffin polisher who eventually landed the role of a lifetime.

But the death notices have got it the wrong way round. Sean Connery was the actor who made James Bond famous. Connery made Bond.

Ian Fleming’s books were of course already hugely popular. So it’s not like the character of Bond was totally unknown. But then there wasn’t all that much character to know.

“I wanted Bond to be an extremely dull, uninteresting man to whom things happened,” Fleming told The New Yorker over a medium-dry Martini with lemon peel. He plucked the name Bond, James Bond from the author of an ornithology book on the shelf at his Jamaican home of Goldeneye: “I thought, ‘My God, that’s the dullest name I’ve ever heard.’”

The literary Bond is a blandly obedient civil servant, a cipher onto which the reader can project his own fantasies. (And I say that as a fan.) What character Bond does have is, off paper if not on it, fairly objectionable. Like Fleming, he’s an old Etonian and a terrible snob.

Fleming wanted David Niven for the role, although he also liked the idea of casting an unknown actor so that “Ian Fleming’s James Bond” could take top billing. He dismissed Connery as “that fucking truck driver”.

Original Bond film producers Harry Salzman and Albert R “Cubby” Broccoli couldn’t possibly have known, or dreamt, how successful their franchise would become. But they did know that an English public schoolboy protagonist wouldn’t translate to the screen, or internationally.

Niven wasn’t tough enough for Broccoli, who first met his future leading man on the set of the 1958 film Another Time, Another Place, where Connery supposedly laid out his co-star Lana Turner’s jealous boyfriend, Los Angeles mob enforcer Johnny Stompanato, when he turned up waving a gun. Broccoli was struck by the “animal virility” of Connery, who had “just the right hint of threat behind that hard smile and faint Scottish burr.”

And while Cary Grant (another Fleming co-sign) was considered, the producers also liked the idea of an unknown, because a star would never sign up for the six-film series they envisaged and besides, they only had $140,000 to spend on the whole cast. They chose to make Dr No, the sixth novel, because they didn’t have the rights to Casino Royale, the first, and because they figured Goldfinger and Thunderball would be more expensive to shoot. The studio, United Artists, were reluctant to make Dr No with an unknown, but they were also reluctant to bet big. The budget was (Dr Evil voice) $1m, for which the producers endeavoured to deliver a $5m film. It came in at $1.2m.

Other names in the frame for Bond were Roger Moore (too young, even though he was older than Connery, and too “pretty”), Patrick McGoohan, Albert Finney, Trevor Howard, Michael Redgrave and Richard Johnson. Broccoli’s wife, Dana, urged her husband to screen-test Connery after being taken by his kissing technique in the 1959 Disney live-action film Darby O’Gill And The Little People (a great Pointless answer). At his first formal meeting with the Bond producers, Connery voiced his opinion - shared by his then wife, actress Diane Cilento, who found the character “relentlessly awful” – that humour was “essential”.

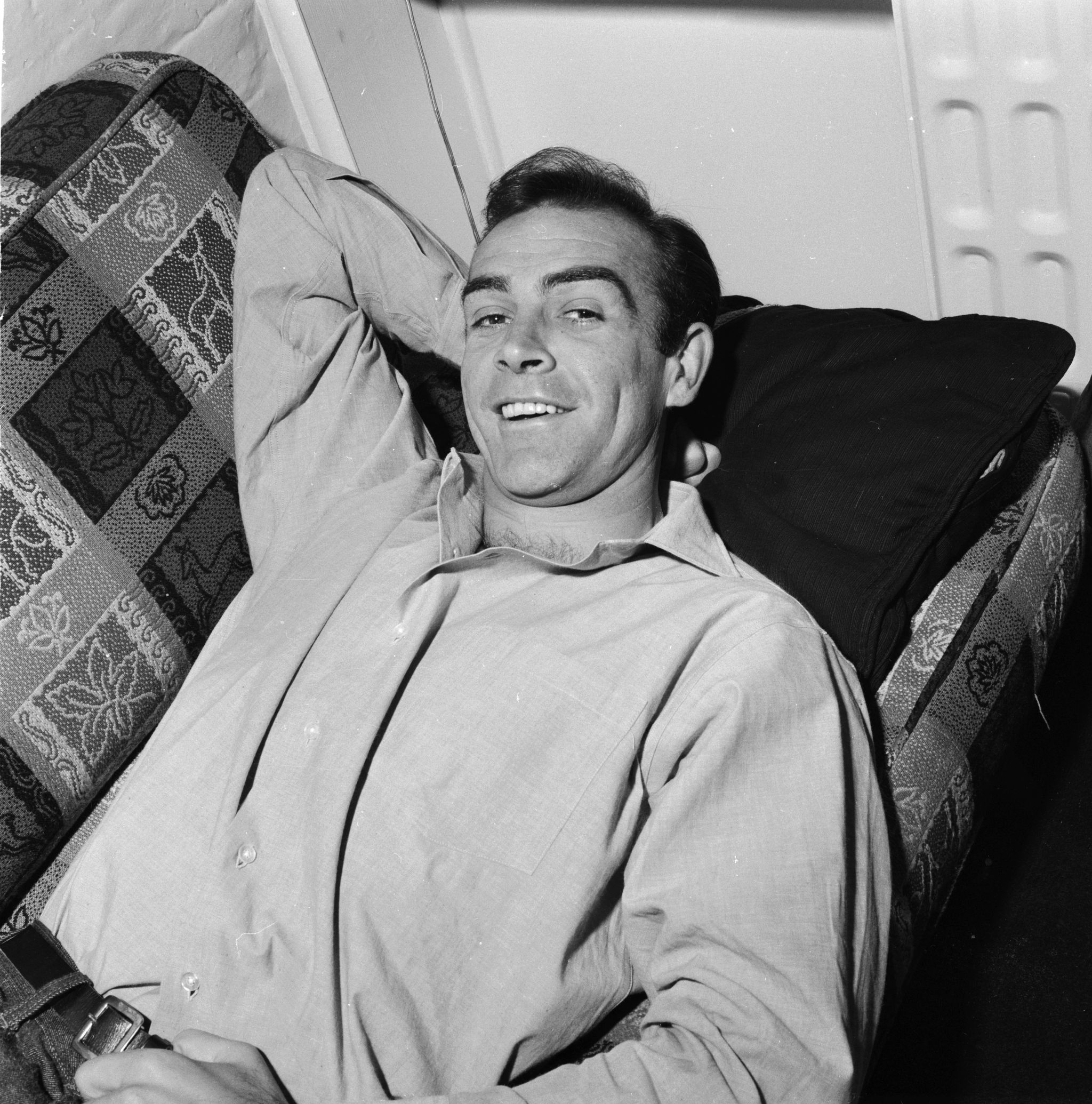

“Whenever he wanted to make a point, he’d bang his fist on the table, the desk or his thigh, and we knew this guy had something,” remembered Salzman. “When he left, we watched from the window as he walked down the street and we all said, ‘He’s got it!’”

It’s hard to overstate how essential Connery was to selling Bond, and the public buying him. While Fleming’s books were on the whole more grounded in reality than the films would later become, they are also, at points, pretty laughable. In the novel Dr No, the titular villain is a former Chinese gangster with hooks for hands who sells bird shit as fertiliser from his island base as a cover for using radio beams to sabotage US rocket tests.

“The books are larger than life,” said Salzman. “As a matter of fact, I think we are closer to life-size than the books are.” Although that didn’t last long. And in one early screenplay for what became the 1962 film Dr No, the titular villain was, um, a monkey, which would’ve at least been less racist than Fleming’s oriental caricature. If the producers had a master plan for world domination, they were hiding it well.

What they did have was Connery. Even then, they didn’t really know until he’d gone, weary of being conflated with the character and upstaged by stupid gadgets, only lured back for 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever with a then-record fee of $1.25m (which he donated to his charity, the Scottish International Educational Trust) plus a 12.5 per cent cut of the gross profits.

And the studio definitely didn’t know what they had. After viewing Connery’s screen test for Dr No, United Artists in New York telegraphed, “NO. KEEP TRYING.” Thankfully, the studio’s London rep lobbied for Connery. And United Artists’ only positive feedback on the finished film, after the initial silence, was at least they couldn’t lose too much money.

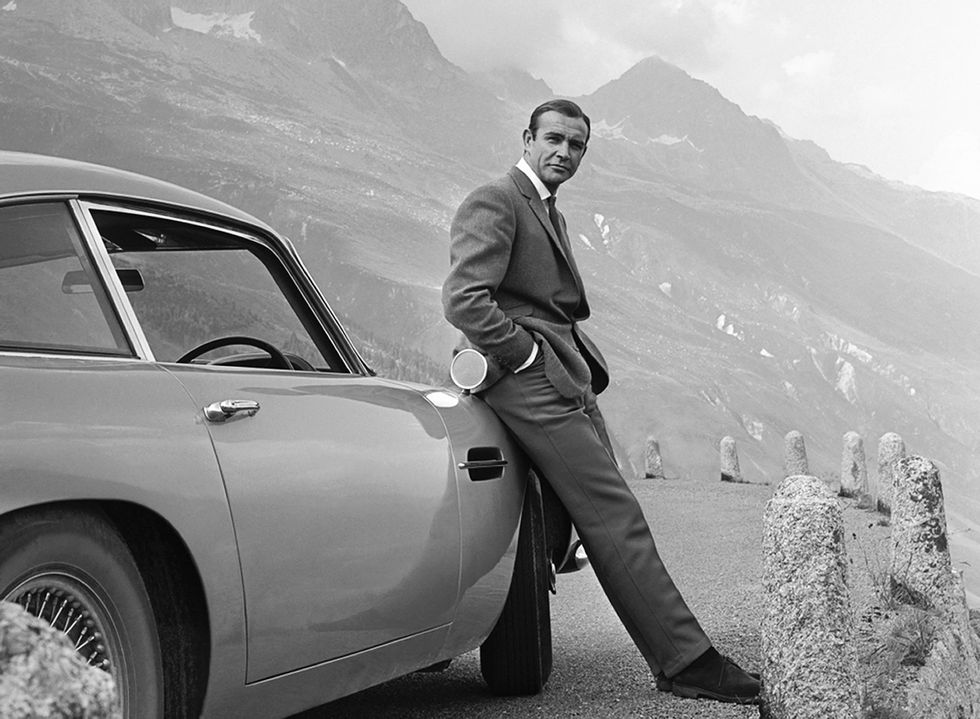

At the premiere, however, “You could feel the buzz in the place, especially the moment he says, ‘Bond, James Bond’ and the music comes in behind him,” Monty Norman, the composer of that theme, told the authors of the book Some Kind Of Hero: The Remarkable Story Of The James Bond Films. “That was an amazing moment.”

That iconic first appearance, teased by director Terence Young, is “of a man so assured of his gorgeousness that almost half a century on it still takes your breath away”, as author and film critic Christopher Bray writes in his 2010 biography Sean Connery: The Measure Of A Man. The way in which Connery purrs the name, it’s anything but dull.

If you want to understand the deathless appeal of Bond, it’s there in those three languid syllables. Pity every other actor past, present and future who is measured against him and found wanting, who has to somehow try and utter that immortal line with even a quantum of that charisma.

“The whole of wanting to be Bond is wanting to be Connery,” writes Bray. “Nobody ever fancied themselves the next Roger Moore.” Harsh, but probably fair. Nobody does it better. Nobody has. Nobody will.

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts

Jamie Millar is a freelance journalist and regular Men’s Health contributor, writing about style, grooming, fitness and culture. Follow @mrjamiemillar