1897-1939

Latest News: An Exploration Team Believes It Found Amelia Earhart’s Missing Plane

Is the 86-year mystery of Amelia Earhart’s disappearance close to being solved? A marine explorer and his team believe they have found her long-lost airplane.

Deep Sea Vision, a marine robotics company led by private pilot Tony Romeo, released a sonar image January 29 depicting a shape similar to the contours of a Lockheed 10-E Electra plane—the same craft Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan were flying when they vanished over the Pacific Ocean in July 1937. The discovery, the exact location of which Deep Sea Vision is keeping a secret, was part of a 90-day search spanning roughly 5,200 square miles of ocean floor. Authorities are working to validate the group’s findings.

Romeo believes the image, taken about 100 miles from Howland Island, supports the “Date Line Theory” surrounding Earhart’s disappearance. This posits that navigator Noonan miscalculated their position by roughly 60 miles after forgetting to account for the International Date Line during their flight and forcing the plane into an ocean landing. “We always felt that [Earhart] would have made every attempt to land the aircraft gently on the water, and the aircraft signature that we see in the sonar image suggests that may be the case,” Romeo said. “We’re thrilled to have made this discovery at the tail end of our expedition, and we plan to bring closure to a great American story.”

Jump to:

- Who Was Amelia Earhart?

- Quick Facts

- Early Life

- Becoming a Pilot

- First Transatlantic Flight as a Passenger

- Book and Celebrity Persona

- First Solo Flight Across the Atlantic by a Woman

- Other Notable Flights

- Husband George Putnam

- Last Flight and Disappearance

- Theories and Investigations Into Earhart’s Disappearance

- Legacy

- Quotes

Who Was Amelia Earhart?

Amelia Earhart, fondly known as “Lady Lindy,” was an American aviator who mysteriously disappeared in July 1937 while trying to circumnavigate the globe from the equator. Earhart was the 16th woman to be issued a pilot’s license. She had several notable flights, including becoming the first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean in 1928, as well as the first person to fly over both the Atlantic and Pacific. Earhart was legally declared dead in 1939.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: Amelia Earhart

BORN: July 24, 1897

DIED: January 5, 1939 (legal declaration of death)

BIRTHPLACE: Atchison, Kansas

SPOUSE: George Putnam (1931-1939)

ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Leo

Early Life

Amelia Earhart was born on July 24, 1897, in Atchison, Kansas. Earhart spent much of her early childhood in the upper-middle-class household of her maternal grandparents. Earhart’s mother, Amelia “Amy” Otis, married a man who showed much promise but was never able to break the bonds of alcohol. Edwin Earhart was on a constant search to establish his career and put the family on a firm financial foundation. When the situation got bad, Amy would shuttle Earhart and her sister Muriel to their grandparents’ home. There they sought out adventures, exploring the neighborhood, climbing trees, hunting for rats and taking breathtaking rides on Earhart’s sled.

Even after the family was reunited when Earhart was 10, Edwin constantly struggled to find and maintain gainful employment. This caused the family to move around, and Earhart attended several different schools. She showed early aptitude in school for science and sports, though it was difficult to do well academically and make friends.

In 1915, Amy separated once again from her husband and moved Earhart and her sister to Chicago to live with friends. While there, Earhart attended Hyde Park High School, where she excelled in chemistry. Her father’s inability to be the provider for the family led Earhart to become independent and not rely on someone else to “take care” of her.

After graduation, Earhart spent a Christmas vacation visiting her sister in Toronto, Canada. After seeing wounded soldiers returning from World War I, she volunteered as a nurse’s aide for the Red Cross. Earhart came to know many wounded pilots. She developed a strong admiration for aviators, spending much of her free time watching the Royal Flying Corps practicing at the airfield nearby. In 1919, Earhart enrolled in medical studies at Columbia University. She quit a year later to be with her parents, who had reunited in California.

Becoming a Pilot

At a Long Beach air show in 1920, Earhart took a plane ride that transformed her life. It was only 10 minutes, but when she landed she knew she had to learn to fly. Working at a variety of jobs, from photographer to truck driver, she earned enough money to take flying lessons from pioneer female aviator Anita “Neta” Snook. Earhart immersed herself in learning to fly. She read everything she could find on flying and spent much of her time at the airfield. She cropped her hair short, in the style of other women aviators. Worried what the other, more experienced pilots might think of her, she even slept in her new leather jacket for three nights to give it a more “worn” look.

In the summer of 1921, Earhart purchased a second-hand Kinner Airster biplane painted bright yellow. She nicknamed it “The Canary,” and set out to make a name for herself in aviation.

On October 22, 1922, Earhart flew her plane to 14,000 feet—the world altitude record for female pilots. On May 15, 1923, Earhart became the 16th woman to be issued a pilot’s license by the world governing body for aeronautics, The Federation Aeronautique.

Throughout this period, the Earhart family lived mostly on an inheritance from Amy’s mother’s estate. Amy administered the funds but, by 1924, the money had run out. With no immediate prospects of making a living flying, Earhart sold her plane. Following her parents’ divorce, she and her mother set out on a trip across the country starting in California and ending up in Boston. In 1925, she again enrolled in Columbia University but was forced to abandon her studies due to limited finances. Earhart found employment first as a teacher, then as a social worker.

Earhart gradually got back into aviation in 1927, becoming a member of the American Aeronautical Society’s Boston chapter. She also invested a small amount of money in the Dennison Airport in Massachusetts and acted as a sales representative for Kinner airplanes in the Boston area. As she wrote articles promoting flying in the local newspaper, she began to develop a following as a local celebrity.

First Transatlantic Flight as a Passenger

After Charles Lindbergh’s solo flight from New York to Paris in May 1927, interest grew for having a woman fly across the Atlantic. In April 1928, Earhart received a phone call from Captain Hilton H. Railey, a pilot and publicity man, asking her, “Would you like to fly the Atlantic?” In a heartbeat, she said yes. She traveled to New York to be interviewed and met with project coordinators, including publisher George Putnam. Soon, she was selected to be the first woman on a transatlantic flight—as a passenger. The wisdom at the time was that such a flight was too dangerous for a woman to conduct herself.

On June 17, 1928, Earhart took off from Trepassey Harbor, Newfoundland, in a Fokker F.Vllb/3m named Friendship. Accompanying her on the flight was pilot Wilmer “Bill” Stultz and co-pilot and mechanic Louis E. “Slim” Gordon. Approximately 20 hours and 40 minutes later, they touched down at Burry Point, Wales, in the United Kingdom. Due to the weather, Stultz did all the flying. Even though this was the agreed upon arrangement, Earhart later confided that she felt she “was just baggage, like a sack of potatoes.” Then she added, “Maybe someday I’ll try it alone.”

The Friendship team returned to the United States, greeted by a ticker-tape parade in New York and later a reception held in their honor with President Calvin Coolidge at the White House. The press dubbed Earhart “Lady Lindy,” a derivative of the “Lucky Lind,” nickname for Lindbergh.

Book and Celebrity Persona

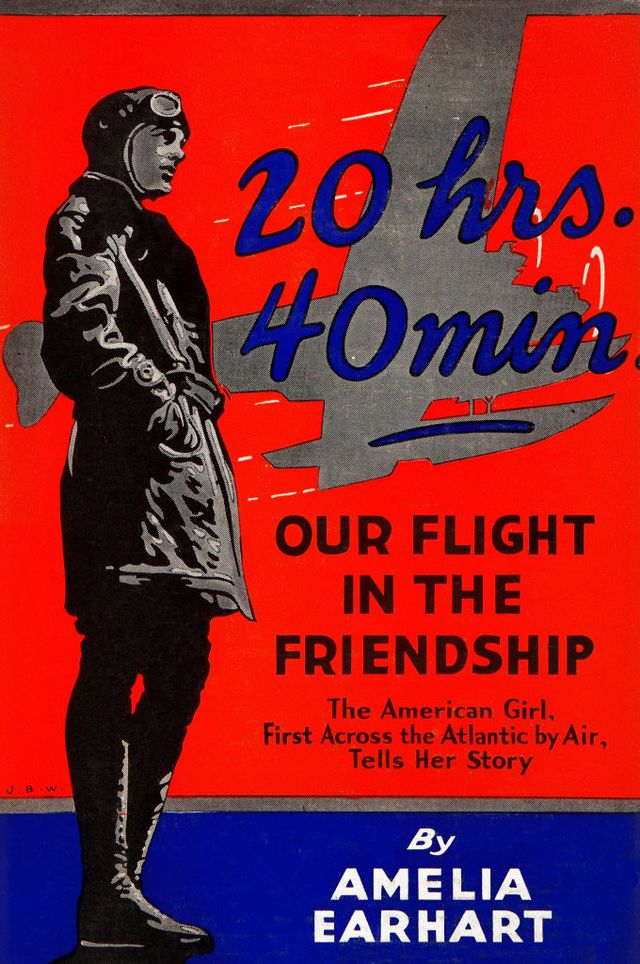

In 1928, Earhart wrote a book about aviation and her transatlantic experience, 20 Hrs., 40 Min. Upon publication that year, Earhart’s collaborator and publisher, George Putnam, heavily promoted her through a book and lecture tours and product endorsements. Earhart actively became involved in the promotions, especially with women’s fashions. For years she had sewn her own clothes, and now she contributed her input to a new line of women’s fashion that embodied a sleek, purposeful, yet feminine look.

Through her celebrity endorsements, Earhart gained notoriety and acceptance in the public eye. She accepted a position as associate editor at Cosmopolitan magazine, using the media outlet to campaign for commercial air travel. From this forum, she became a promoter for Transcontinental Air Transport, later known as Trans World Airlines (TWA), and was a vice president of National Airways, which flew routes in the northeast.

Earhart’s public persona presented a gracious and somewhat shy woman who displayed remarkable talent and bravery. Yet deep inside, Earhart harbored a burning desire to distinguish herself as different from the rest of the world. She was an intelligent and competent pilot who never panicked or lost her nerve, but she was not a brilliant aviator. Her skills kept pace with aviation during the first decade of the century, but as technology moved forward with sophisticated radio and navigation equipment, Earhart continued to fly by instinct.

She recognized her limitations and continuously worked to improve her skills, but the constant promotion and touring never gave her the time she needed to catch up. Recognizing the power of her celebrity, she strove to be an example of courage, intelligence, and self-reliance. She hoped her influence would help topple negative stereotypes about women and open doors for them in every field.

Earhart set her sights on establishing herself as a respected aviator. Shortly after returning from her 1928 transatlantic flight, she set off on a successful solo flight across North America. In 1929, she entered the first Santa Monica-to-Cleveland Women’s Air Derby, placing third. In 1931, Earhart powered a Pitcairn PCA-2 autogyro and set a world altitude record of 18,415 feet. During this time, Earhart became involved with the Ninety-Nines, an organization of female pilots advancing the cause of women in aviation. She became the organization’s first president in 1930.

First Solo Flight Across the Atlantic by a Woman

On May 20, 1932, Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, in a nearly 15-hour voyage from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, to Culmore, Northern Ireland. Before their marriage, Earhart and George Putnam worked on secret plans for a solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. By early 1932, they had made their preparations and announced that, on the fifth anniversary of Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic, Earhart would attempt the same feat.

Earhart took off in the morning from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, with that day’s copy of the local newspaper to confirm the date of the flight. Almost immediately, the flight ran into difficulty as she encountered thick clouds and ice on the wings. After about 12 hours the conditions got worse, and the plane began to experience mechanical difficulties. She knew she wasn’t going to make it to Paris as Lindbergh had, so she started looking for a new place to land. She found a pasture just outside the small village of Culmore, in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, and successfully landed.

On May 22, 1932, Earhart made an appearance at the Hanworth Airfield in London, where she received a warm welcome from local residents. Earhart’s flight established her as an international hero. As a result, she won many honors, including the Gold Medal from the National Geographic Society, presented by President Herbert Hoover; the Distinguished Flying Cross from the U.S. Congress; and the Cross of the Knight of the Legion of Honor from the French government.

Other Notable Flights

Earhart made a solo trip from Honolulu to Oakland, California, establishing her as the first person to fly both across the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. In April 1935, she flew solo from Los Angeles to Mexico City, and a month later, she flew from Mexico City to New York. Between 1930 and 1935, Earhart set seven women’s speed and distance aviation records in a variety of aircraft. In 1935, Earhart joined the faculty at Purdue University as a female career consultant and technical advisor to the Department of Aeronautics, and she began to contemplate one last fight to circle the world.

Husband George Putnam

On February 7, 1931, Earhart married George Putnam, the publisher of her autobiography, at his mother’s home in Connecticut.

Putnam had already published several writings by Lindbergh when he saw Earhart’s 1928 transatlantic flight as a best-selling story with Earhart as the star. Putnam, who was married to Crayola heiress Dorothy Binney Putnam, invited Earhart to move into their Connecticut home to work on her book.

Earhart became close friends with Dorothy, but rumors surfaced about an affair between Earhart and Putnam, who both insisted the early part of their relationship was strictly professional. Unhappy in her marriage, Dorothy was having an affair with her son’s tutor, according to Whistled Like a Bird by Sally Putnam Chapman, Dorothy’s grandaugther. The Putnams divorced in 1929.

Soon after their split, Putnam actively pursued Earhart, asking her to marry him on several occasions. Earhart declined before eventually agreeing. On the day of their wedding, Earhart wrote a letter to Putnam telling him, “I want you to understand I shall not hold you to any medieval code of faithfulness to me nor shall I consider myself bound to you similarly.”

Last Flight and Disappearance

Earhart’s attempt to be the first person to circumnavigate the earth around the equator ultimately resulted in her disappearance on July 2, 1937. Earhart purchased a Lockheed Electra L-10E plane and pulled together a top-rated crew of three men: Captain Harry Manning, Fred Noonan, and Paul Mantz. Manning, who had been the captain of the President Roosevelt, which brought Earhart back from Europe in 1928, would become Earhart’s first navigator. Noonan, who had vast experience in both marine and flight navigation, was to be the second navigator. Mantz, a Hollywood stunt pilot, was chosen to be Earhart’s technical advisor.

The original plan was to take off from Oakland, California, and fly west to Hawaii. From there, the group would fly across the Pacific Ocean to Australia. Then, they would cross the sub-continent of India, on to Africa, then to Florida, and back to California.

On March 17, 1937, they took off from Oakland on the first leg. They experienced some periodic problems flying across the Pacific and landed in Hawaii for some repairs at the United States Navy’s Field on Ford Island in Pearl Harbor. After three days, the Electra began its takeoff, but something went wrong. Earhart lost control and looped the plane on the runway. How this happened is still the subject of some controversy. Several witnesses, including an Associated Press journalist, said they saw a tire blow. Other sources, including Paul Mantz, indicated it was a pilot error. Although no one was seriously hurt, the plane was severely damaged and had to be shipped back to California for extensive repairs.

In the interim, Earhart and Putnam secured additional funding for a new flight. The stress of the delay and the grueling fund-raising appearances left Earhart exhausted. By the time the plane was repaired, weather patterns and global wind changes required alterations to the flight plan. This time Earhart and her crew would fly east. Captain Harry Manning would not join the team, due to previous commitments. Paul Mantz was also absent, reportedly due to a contract dispute.

After flying from Oakland to Miami, Earhart and Noonan took off on June 1 from Miami with much fanfare and publicity. The plane flew toward Central and South America, turning east for Africa. From there, the plane crossed the Indian Ocean and finally touched down in Lae, New Guinea, on June 29, 1937. About 22,000 miles of the journey had been completed. The remaining 7,000 miles would take place over the Pacific.

In Lae, Earhart contracted dysentery that lasted for days. While she recuperated, several necessary adjustments were made to the plane. Extra amounts of fuel were stowed on board. The parachutes were packed away, for there would be no need for them while flying along the vast and desolate Pacific Ocean.

The flyers’ plan was to head to Howland Island, 2,556 miles away, situated between Hawaii and Australia. A flat sliver of land 6,500 feet long, 1,600 feet wide, and no more than 20 feet above the ocean waves, the island would be hard to distinguish from similar-looking cloud shapes. To meet this challenge, Earhart and Noonan had an elaborate plan with several contingencies. Celestial navigation would be used to track their routes and keep them on course. In the case of overcast skies, they had radio communication with a U.S. Coast Guard vessel, Itasca, stationed off Howland Island. They could also use their maps, compass and the position of the rising sun to make an educated guess in finding their position relative to Howland Island.

After aligning themselves with Howland’s correct latitude, they would run north and south looking for the island and the smoke plume to be sent up by the Itasca. They even had emergency plans to ditch the plane if need be, believing the empty fuel tanks would give the plane some buoyancy, as well as time to get into their small inflatable raft to wait for rescue.

Earhart and Noonan set out from Lae on July 2, 1937, at 12:30 a.m., heading east toward Howland Island. Although the flyers seemed to have a well-thought-out plan, several early decisions led to grave consequences later on. Radio equipment with shorter wavelength frequencies were left behind, presumably to allow more room for fuel canisters. This equipment could broadcast radio signals farther distances. Due to inadequate quantities of high-octane fuel, the Electra carried about 1,000 gallons—50 gallons short of full capacity.

The Electra’s crew ran into difficulty almost from the start. Witnesses to the July 2 takeoff reported that a radio antenna might have been damaged. It is also believed that, due to the extensive overcast conditions, Noonan might have had extreme difficulty with celestial navigation. If that weren’t enough, it was later discovered that the flyers were using maps that may have been inaccurate. According to experts, evidence shows that the charts used by Noonan and Earhart placed Howland Island nearly six miles off its actual position.

These circumstances led to a series of problems that couldn’t be solved. As Earhart and Noonan reached the supposed position of Howland Island, they maneuvered into their north and south tracking route to find the island. They looked for visual and auditory signals from the Itasca, but for various reasons, radio communication was very poor that day. There was also confusion between Earhart and the Itasca over which frequencies to use, and a misunderstanding as to the agreed upon check-in time; the flyers were operating on Greenwich Civil Time and the Itasca was operating on the naval time zone, which set their schedules 30 minutes apart.

On the morning of July 2, 1937, at 7:20 a.m., Earhart reported her position, placing the Electra on a course at 20 miles southwest of the Nukumanu Islands. At 7:42 a.m., the Itasca picked up this message from the Earhart: “We must be on you, but we cannot see you. Fuel is running low. Been unable to reach you by radio. We are flying at 1,000 feet.” The ship replied, but there was no indication that Earhart heard this. The flyers’ last communication was at 8:43 a.m. Although the transmission was marked as “questionable,” it is believed Earhart and Noonan thought they were running along the north-south line. However, Noonan’s chart of Howland’s position was off by 5 nautical miles. The Itasca released its oil burners in an attempt to signal the flyers, but they apparently didn’t see it. In all likelihood, their tanks ran out of fuel, and they had to ditch at sea.

When the Itasca realized that they had lost contact, they began an immediate search. Despite the efforts of 66 aircraft and nine ships—an estimated $4 million rescue authorized by President Franklin D. Roosevelt—the fate of the two flyers remained a mystery. The official search ended on July 18, 1937, but Putnam financed additional search efforts, working off tips of naval experts and even psychics in an attempt to find his wife. In October 1937, he acknowledged that any chance of Earhart and Noonan surviving was gone. On January 5, 1939, Earhart was declared legally dead by the Superior Court in Los Angeles.

Theories and Investigations Into Earhart’s Disappearance

Since her disappearance, several theories have formed regarding Earhart's last days, many of which have been connected to various artifacts that have been found on Pacific islands. Two seem to have the greatest credibility. One is that the plane that Earhart and Noonan were flying was ditched or crashed, and the two perished at sea. Several aviation and navigation experts support this theory, concluding that the outcome of the last leg of the flight came down to “poor planning, worse execution.” Investigations concluded that the Electra aircraft wasn’t fully fueled and couldn’t have made it to Howland Island even if conditions were ideal. The fact that there were so many issues creating difficulties lead investigators to the conclusion that the plane simply ran out of fuel some 35 to 100 miles off the coast of Howland Island.

Another theory is that Earhart and Noonan might have flown without radio transmission for some time after their last radio signal, landing at uninhabited Nikumaroro reef, a tiny island in the Pacific Ocean 350 miles southeast of Howland Island. This island is where they would ultimately die. This theory is based on several on-site investigations that have turned up artifacts such as improvised tools, bits of clothing, an aluminum panel and a piece of Plexiglas the exact width and curvature of an Electra window. In May 2012, investigators found a jar of freckle cream on a remote island in the South Pacific, in proximity to their other findings, that many investigators believe belonged to Earhart.

Amelia Earhart Photo and Amelia Earhart: The Lost Evidence

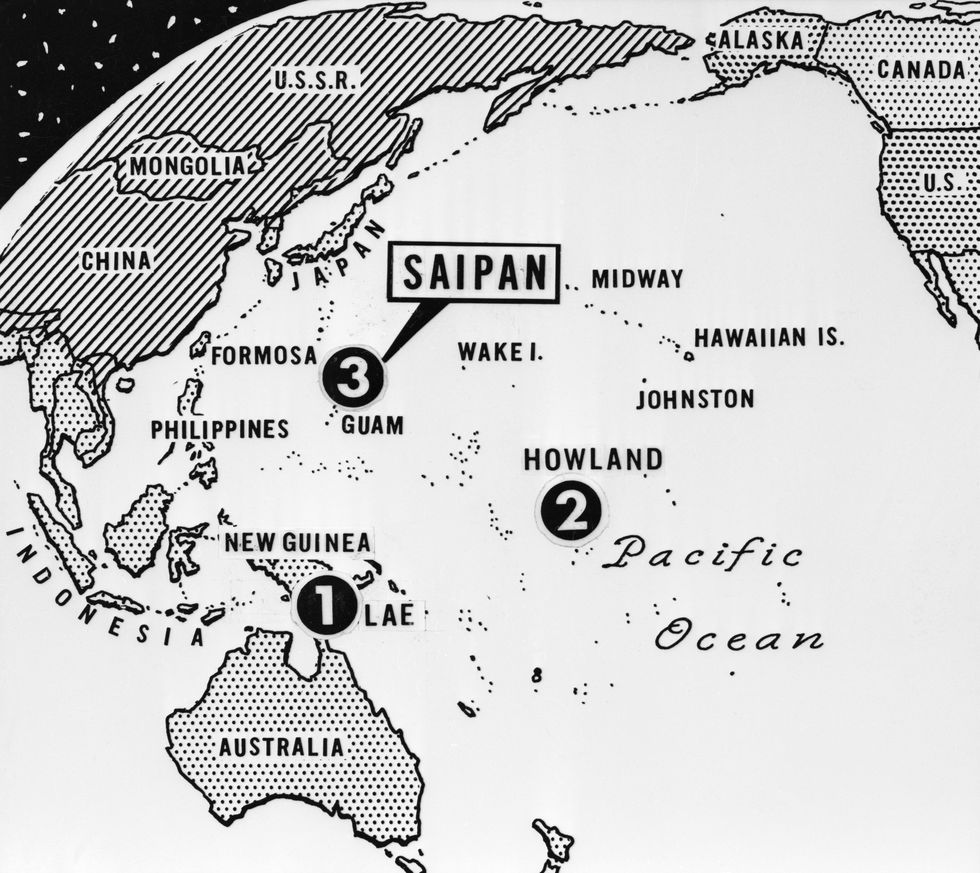

Amelia Earhart: The Lost Evidence was an investigative special on History that aired in July 2017 exploring the significance of a photograph discovered by a retired federal agent in the National Archives. The photograph, which surfaced another theory about Earhart’s disappearance, was supposedly taken by a spy on Jaluit Island and has been found to be unaltered. A facial-recognition expert interviewed in the History special believes that a woman and man in the photo are good matches for Earhart and Noonan (a male figure has a hairline like Noonan’s). In addition, a ship is seen towing an object that aligns with the measurements of Earhart’s plane. The claim is if Earhart and Noonan landed there, the Japanese ship Koshu Maru was in the area and could have taken them and the plane to Jaluit before bringing them, as prisoners, to Saipan.

Some experts have questioned this theory. Earhart expert Richard Gillespie, who leads The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), told The Guardian that the photo was “silly.” TIGHAR, which has been investigating Earhart’s disappearance since the 1980s, believes that running out of fuel, Earhart and Noonan landed on Nikumaroro’s reef and lived as castaways before dying on the atoll. According to another article in The Guardian, in July 2017 a Japanese military blogger found the same photo in a Japanese-language travelogue archived in Japan’s national library, and the picture was published in 1935—two years before Earhart’s disappearance. The communications director of the National Archives told NPR that the archives don’t know the date of the photograph or the photographer.

Plane

In October 2014, it was reported that researchers at TIGHAR found a 19 inch by 23-inch scrap of metal on Nikumaroro’s reef that the group identified as a fragment of Earhart’s plane. The piece was found in 1991 in a small, uninhabited island in the southwestern Pacific.

Bones

In July 2017, a team of four forensic bone-sniffing dogs with TIGHAR and the National Geographic Society claimed to have found the spot where Earhart might have died. In 1940, a British official reported finding human bones beneath a ren tree. Future expeditions found potential signs of an American female castaway, including campfire remains and a woman’s compact. The TIGHAR team said all four of their dogs alerted investigators of human remains near a ren tree and sent samples of the soil to a lab in Germany for DNA analysis.

In 2018, anthropologist Richard Jantz announced the results of a study in which he reexamined the original forensic analysis of the bones discovered in 1940. The original analysis determined the bones to possibly be from a short, stocky European male, but Jantz noted that the scientific techniques used at the time were still being developed.

After comparing the bone measurements to data from 2,776 other people from the time period, and studying photos of Earhart and her clothing measurements, Jantz concluded that there was a likely match. “This analysis reveals that Earhart is more similar to the Nikumaroro bones than 99 percent of individuals in a large reference sample,” he said. “This strongly supports the conclusion that the Nikumaroro bones belonged to Amelia Earhart.”

Radio Signals

Complementing the results of the bone analysis, in July 2018, TIGHAR executive director Richard Gillespie released a report built around years of analysis of radio distress signals sent by Earhart in the days after her disappearance.

Hypothesizing that Earhart and Noonan came down on Nikumaroro reef, the only place large enough to land a plane in the vicinity, Gillespie studied tide patterns and determined that the distress signals corresponded with the reef's low tides, the only time Earhart could run the plane’s engine without fear of flooding.

Furthermore, various citizens documented the reception of messages from Earhart via radio, their accounts corroborated by publications from the time. On July 4, two days after the crash, a San Francisco resident heard a voice from the radio saying, “Still alive. Better hurry. Tell husband all right.” Three days later, someone in eastern Canada picked up the message, “Can you read me? Can you read me? This is Amelia Earhart… please come in,” believed to be the final verifiable transmission from the pilot.

Robert Ballard-National Geographic Search

In August 2019, famed explorer Robert Ballard, who found the Titanic in 1985, led a research team to Nikumaroro with the hope of uncovering more answers about Earhart’s disappearance. The search was sponsored by National Geographic, which planned to air a two-hour documentary about Ballard’s efforts later in the year.

Deep Sea Vision Sonar Image

In January 2024, the Deep Sea Vision exploration team announced it had obtained a sonar image of an object on the Pacific Ocean floor similar to the contours of a Lockheed 10-E Electra—the same type of plane that disappeared with Earhart—and planned to continue to examine the area.

The group and its CEO, Tony Romeo, scanned about 5,200 square miles of unsearched ocean floor over three months to obtain the image. While the exact location of the find hasn’t been publicly disclosed, it’s believed to be about 100 miles from Howland Island. Romeo and DSV believe the object could be Earhart’s plane based on the “Date Line Theory,” suggesting navigator Noonan failed to account for the International Date Line during the flight, which led to a geographic miscalculation.

Legacy

Earhart’s life and career have been celebrated for the past several decades on “Amelia Earhart Day,” which is held annually on July 24—her birthday.

Earhart possessed a shy, charismatic appeal that belied her determination and ambition. In her passion for flying, she amassed a number of distance and altitude world records. But beyond her accomplishments as a pilot, she also wanted to make a statement about the role and worth of women. She dedicated much of her life to prove that women could excel in their chosen professions just like men and have equal value. This all contributed to her wide appeal and international celebrity. Her mysterious disappearance, added to all of this, has given Earhart lasting recognition in popular culture as one of the world’s most famous pilots.

Quotes

- The woman who can create her own job is the woman who will win fame and fortune.

- Adventure is worthwhile in itself.

- Preparation, I have often said, is rightly two-thirds of any venture.

- In my life, I had come to realize that when things were going very well, indeed, it was just the time to anticipate trouble.

- Courage is the price that life exacts for granting peace.

- I have a feeling there is just about one more good flight left in my system, and I hope this trip is it. [said to reporters before her last flight]

- As soon as I left the ground, I knew I myself had to fly. [after her first airplane ride]

- I’ve had practical experience and know the discrimination against women in various forms of industry. A pilot’s a pilot. I hope that such equality could be carried out in other fields so that men and women may achieve equally in any endeavor they set out.

- The time to worry is three months before a flight. Decide then whether or not the goal is worth the risks involved. If it is, stop worrying. To worry is to add another hazard.

- As far as I know I’ve only got one obsession—a small and probably typically feminine horror of growing old—so I won’t feel completely cheated if I fail to come back.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us!

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.