BES: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GOD, FIGHTER, DANCER, COMPANION

Delve into some of the fascinating depictions of Bes, the fierce but joyful ancient Egyptian god

Kyle Jordan

5-minute read

By Kyle Jordan

Curating for Change Fellow at the Ashmolean & Pitt Rivers Museum

In ancient Egypt, there were about 1,400 gods and goddesses who were revered by the ancient inhabitants of the banks of the river Nile for almost 6,000 years.

We recognise a few to this day. Amun-Ra, the solar god of creation. Horus, the falcon god of kingship. Hathor, the celestial goddess of motherhood, beauty and joy. Osiris, the reanimated god of the ‘otherworld’, where the souls of the dead journeyed to be judged.

Many more of these gods and goddesses were found beyond the confines of any temple walls, and among the rhythms of the daily lives of the everyday Egyptian.

Perhaps none more so than the striking character of the god Bes.

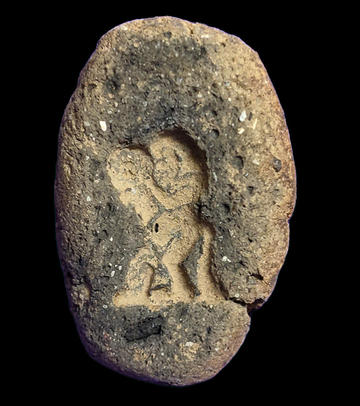

Faience amulet of the ancient Egyptian dwarf god Bes nursing a Horus, 900–400 BCE, AN1932.736 © Ashmolean Museum

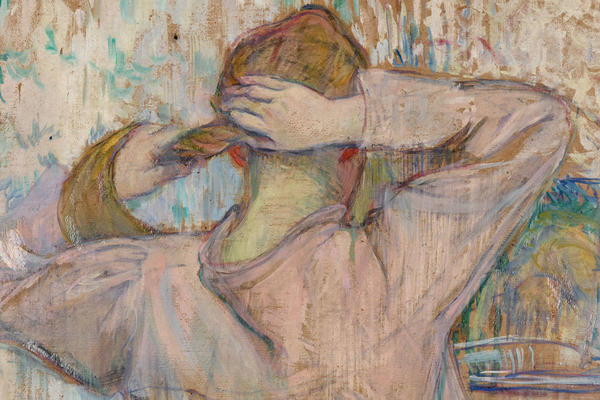

DEPICTIONS OF BES

Bes is depicted as a man of short stature – sometimes the result of a condition we refer to as dwarfism today – and as having strong muscles, a large belly, and a very expressive face. At one moment smiling with his tongue sticking out, and in another snarling and fearsome.

Like many of the Egyptian gods, he embodies both human and animal qualities. He has a lion’s tail and mane, as well as a cat-like nose and ears.

Sometimes naked and sometimes clothed with a kilt or leonine skin and a crown of plumed feathers, Bes’ iconography is striking for the fact he is often presented with a front profile. As opposed to the side-profile we’re so often accustomed to in most Egyptian art.

In this way, Bes directly faces his viewer, locking eyes with them either with playfulness or ferociousness.

But who exactly was Bes, and what was his significance to the Egyptians?

BES THE FIGHTER

Much like the other gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt who exhibited leonine features – most notably the goddesses Sekhmet and Bastet, the lioness and cat deities of warfare and household protection, respectively – Bes was also seen as a warrior and protector. He had a special responsibility for pregnant women, mothers and their infant children.

In this guise, we typically find Bes with a snarling face, an assertive posture and a large knife raised in one hand.

The Egyptians believed that he stood guard during childbirth, ready to strike any malevolent forces that sought to harm both mother and child.

Miniature limestone stela of Bes the Fighter, c 715–332 BCE. AN1878.47 © Ashmolean Museum

He was so well regarded in this role that we often find his image accompanying depictions of the falcon god Horus as an infant, who had to be hidden away from his treacherous uncle Seth.

One particularly common household item was the 'cippi' or 'cippus stelae' (magical protective statues). These were small depictions of Bes watching over Horus, who throttles and tramples malevolent forces in the form of snakes, scorpions, and other wild beasts. The Egyptians believed that pouring clean water over these stelae would transform them into a remedy for curing various ailments.

In this way, Bes not only protected children but also helped them grow strong and resilient.

Just as he aided in the nursing of Horus, his image was integrated into key tools for infant care, such as feeding bottles.

These bottles could also be used to feed those of all ages who, for one reason or another, could not ingest solid foods.

Left: Horus stela standing on two crocodiles, AN1874.279.a (on display). Right: Bottle in the shape of a Bes head, AN1892.1090 © Ashmolean Museum

The image of Bes the Fighter was so widely recognised that we see him adopted into other cultures.

The Romans, for example, were so enamoured with him that we find depictions of him prepared to fight, with the addition of a Roman military uniform, not only in Egypt but across the Empire.

Terracotta figure of Bes as a Roman soldier (on display) AN1896-1908.E.3716 © Ashmolean Museum

BES THE DANCER

However, Bes didn't always resort to violence or aggression in order to protect both the divine and mortals.

He also liked to practise the art of music and dance, taking on a more playful posture with active movement and tongue stuck out. His favourite instruments included the tambourine, for its loud and rhythmic quality.

This image of a mould shows a popular form of amulet, possibly worn by performers who wished to emulate Bes' playfulness.

Mould for creating an amulet of Bes holding a tambourine. AN1893.1-41.689 © Ashmolean Museum

While Bes the Fighter dealt with threats to the physical body, Bes the Dancer dealt with threats to the heart, which the Egyptians believed was the centre of all thought and emotion. By keeping the heart joyful and content through dance, Bes warded off spirits who might otherwise bring malice or sorrow.

Dance and music were important functions of both festivals and celebrations, but also within the daily rituals of palaces and temples, for even the hearts of both pharaohs and gods needed protecting.

This may explain why throughout Egyptian history, we find so many examples of court and temple dancers who were born with dwarfism or had short stature.

BES THE COMPANION

Despite mothers and children being his main charge, Bes’ reputation for both ferocity and joviality meant he was a popular companion in many other spheres of Egyptian life.

His face adorned the entranceways to houses, meant to ward off pests, poisonous insects and disease from entering the home. We also find his image on bed-posts, to ensure a safe and restful night's sleep for the occupant, free from nightmares.

Beyond the home, his face can be found on jars and storage vessels of various sizes, protecting trade produce that finds its way to places like Cyprus, the Levant and Mesopotamia.

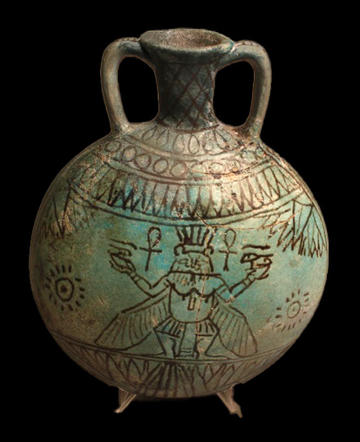

Pilgrims and travellers heading for religious festivities would carry flasks decorated with his image, such as this one below from the Ashmolean's collection.

Here we see Bes not only with his typical leonine features, but also with the addition of wings, balancing the udjat eyes in both hands while two ankhs flank his face. In this visage, Bes is shown as just, balancing eternity and providing life force to the drinker.

Faience pilgrim flask decorated with a figure of Bes. AN1890.897 © Ashmolean Museum

So trusted was he as a companion, some would take his image with them into the life everlasting. The Duat – the place where the dead journeyed in order to reach the afterlife – was full of dangers, and so Bes’ protection would be greatly desired.

This string of beads found in a grave at the site of Faras in Lower Nubia – a place of frequent interaction and exchange between both Egypt and their southern Nubian neighbours – incorporates several heads of Bes, along with images of Amun and crocodiles.

Carnelian ball beads separating faience amulets of Bes heads, crocodile, glaze beads. AN1912.429 © Ashmolean Museum

BES IN THE MUSEUM & EXPLORING DISABILITY IN OUR COLLECTIONS

Discover some of these depictions of Bes on the Ashmolean's ground floor, in the Egypt in the Age of the Empires gallery.

There will be more displays, events and trails coming in November 2023 to mark Disability History Month and as part of our celebration of the Curating for Change programme that Kyle Jordan is leading on at the Ashmolean and the Pitt Rivers Museum.