California Girl: The Unknown Art of Edie Sedgwick

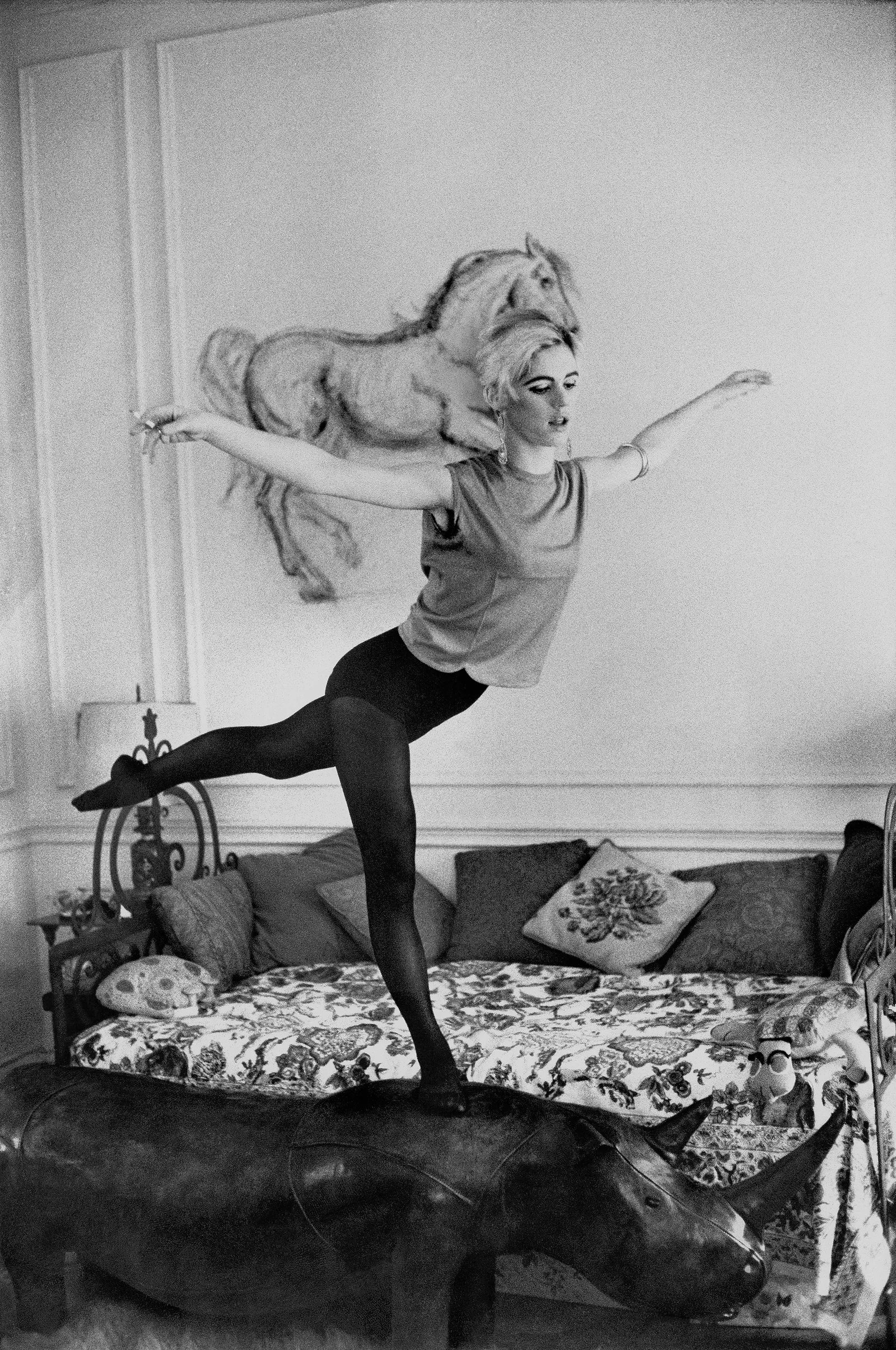

Edie Sedgwick with one of her horses in New York City, August 1965, by Enzo Sellerio for Vogue

Italian-greyhound thin and tiny, with shapely long dancing legs in opaque black stockings. Thick black eyeliner, mascara, and dark shadow like Elizabeth Taylor’s in Cleopatra (1963). Brunette hair bleached atomic blonde, dyed silver for good measure. Striped pull marin Breton sailor’s shirts, long enough to tug down and wear as the micro miniskirts she favored and popularized. With her slight build, wide innocent dark eyes, and radiant smile, she looked more like a teenage girl than a young woman when she became a New York City sensation in early 1965, at the age of 21. Edith Minturn “Edie” Sedgwick, in her black-and-white public persona from 1965 to 1969, was rightly called “superstar.” Photographs of her with Andy Warhol—snuggled against him in a banquette, emerging from a manhole in a Manhattan street, in stills from the movies he compulsively filmed to showcase her—are the most iconic images of that slim wild slice of life that spattered and flashed like a sparkler at The Factory on East 47th Street. Edie was the it girl of that place and time, the most beautiful and the most wanted, the most objectified by the throngs of men around her, the New York doll. It seems sometimes, reading accounts of those days, and reviewing the photographs and movies, as if Edie simply materialized, walking into a crowded hot room one night, dressed that way, looking like that, while the Velvet Underground were playing. New York City brought her attention, celebrity, and pain—but never, ever forget that Edith Minturn Sedgwick was a California girl. A previously unknown cache of her original artwork celebrates what Edie loved most, and the roots to which she returned at what turned out to be the end of her life: the golden hills of home, and what she loved in them.

Edie was born on a spring day in April 1943 in Santa Barbara, California, and grew up on her family’s ranches in Santa Ynez—properties both vast, covering many thousands of acres, and crowded, for Edie was the seventh of right children of Francis and Alice Sedgwick. The lovely little girl was first put on a horse when she was a toddler, just over a year old, and became an expert rider while quite young. It was her freedom and passion, to saddle up her pony or not even bother with the saddle, just to catch a horse and head out into the land. Said her brother Jonathan, years later, “I always thought Edie wanted to escape on her horse, but she couldn’t get off the ranch. She was penned in. Usually it started with a battle with my father. She always felt that he would come and get her. So she could only run away on the ranch. She would just disappear into the mountains with her horse, Chub, and you never knew where she was. Then she’d come back mellowed out.”

Edie Sedgwick, figure study of horses

Edie similarly despised the constraining boarding schools to which she was sent, first in California and then back East; she developed eating disorders there, and was hospitalized at a Connecticut psychiatric hospital, at her father’s insistence, when she was nineteen. A year later, she moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts and began studying art with her cousin Lily Swann Saarinen (by then divorced from her architect husband Eero). In November 1963, Edie’s mother Alice wrote to Lily, “This is really nice of you to take Edie on, as a pupil. It will be wonderful for her, in every respect. I am sending her portfolio of drawings, also some of her ceramic work, etc., which she ought to receive early next week. Within the limits of your convenience, I hope Edie will work regular hours & a regular number of hours, even on the days she does not have a lesson.”

Edie Sedgwick, white horse, similar to her sculptures done while Lily Saarinen’s student

Edie’s art studies ended in early 1964. Her mother was hopeful that Edie would come home after another period of ill health, and partygoing with Harvard and Radcliffe students. Alice wrote to Lily that spring: “the best plan, in everyone’s opinion, is to get her to come west, with Jonathan, on May 28th. Then we can talk with her & make future plans, while she cannot help but change her night-into-day present pattern. She’s a superb horsewoman, she can help me with some newly trained colts…Indeed, we all seem to have our problems with our young & so have they within themselves!” It wasn’t to be. Having turned 21 in April 1964, and inherited at that point a legacy from her mother’s mother that gave her her own money, Edie moved to New York and began a modeling career. That July, Alice was encouraged by Edie’s having an interview with Mademoiselle, and thought it all right for her to stay in New York just a little longer: “She seems to have settled down, quite a bit, so we’ll just wait & see.” Three things then happened in swift order: Edie’s brothers Francis Jr. and Robert both died; and she met Andy Warhol.

In a series of audio interviews recorded in 1970, Sedgwick recalled the underside of her first glamorous days as a New York celebrity, in 1965: “I was kind of turned off for the time being, going out with men, because I was very upset that two of my brothers had committed suicide, two that I loved very much. It had kind of screwed up my head, so I just freaked out for awhile. Then I must say I liked the introduction to drugs I received. I was a good target for the scene, I blossomed into a healthy young drug addict. I can have a sense of humor about it now, but for a couple of years it wasn’t very funny.” She was the face and figure of wild youth in the city that never sleeps, the luminous waif whose vital beauty fueled Warhol’s Factory and brought him increased celebrity and attention as a filmmaker, something he had always wanted to be. Edie was his star—for a while. Looking back five light-years later, Edie called it like it was. “While I was ‘girl of the year’ and ‘superstar’ and all that crap, everything I did was really underneath I guess motivated by psychological disturbance. But I’d make a mask out of my face, cause I didn’t realize I was quite beautiful. It’s taken me twenty-seven years to realize it, and practically destroy it. But I had to wear heavy black eyelashes like bat wings, and dark lines under my eyes, cut all my hair off, my long dark hair, cut it off and strip it silver and blond. All these little maneuvers I did out of things that were happening in my life that upset me; I’d freak out in a very physical way. And, um, it was all taken as a fashion trend.”

Sedgwick left the New York scene and went home to California to recover from her ongoing addiction and substance abuse problems, and a few failed love affairs, most notably with musician and artist Bobby Neuwirth in 1967. Her work on the semi-autobiographical movie Ciao! Manhattan (1972) occupied her between stints in the Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital. In 1970, Sedgwick lamented her loneliness: “I moved out to Santa Barbara, to straighten out, supposedly, and I started rollicking around with all kinds of kids a lot younger than me. I had fun, but I really didn’t have anyone I particularly loved….I haven’t been in love with anyone in years and years. But I have a certain amount of faith that it’ll come.” It did. In the summer of 1970, while at the Cottage Hospital, Sedgwick met Michael Post, 20, a student and fellow patient. On July 24, 1971, they were married. Edie Post died four months later, on November 16, 1971, after relapsing into barbiturate and alcohol use. She was twenty-eight years old.

Michael and Edie, July 24, 1971

* * * *

Michael Post, now 72, was easy to spot on the Santa Monica pier one sunny morning. Tall and handsome, his dark hair and beard now regal sweeps of white, he was in a blue Hawaiian print shirt of elegant, calm pattern and smiling out at the sea while he waited for me. He’d invited me to lunch to talk about Edie and her art. “She loved her horses best,” he said, of the prancing animals she most loved to draw. Early sketches show Sedgwick working out the forms of legs and shoulders, withers and necks she’d known all her life as a constant rider. “It was when she felt most free,” says Post. “She’d go up to the ranch, catch one of the horses, and just ride up into the hills.” He looked inland, at the sunburned chapparal rising above little clusters of houses. “On a horse they could be her place, just her alone, those golden California hills.”

Edie Sedgwick, horse head

Her love of fauna is clear, and full of joy. Other critters spice Sedgwick’s drawings. Her little raccoon has elegant paws, as it trit-trots on its way, carrying a rather precarious baby raccoon, catlike, in its mouth. I wondered if Edie saw, in the creature’s well-turned eyes and their surrounding mask, a correspondence to her own thickly drawn makeup. There is a sassy cartoon rat, straight out of a saloon in his cowboy boots.

Edie Sedgwick, raccoon and kit

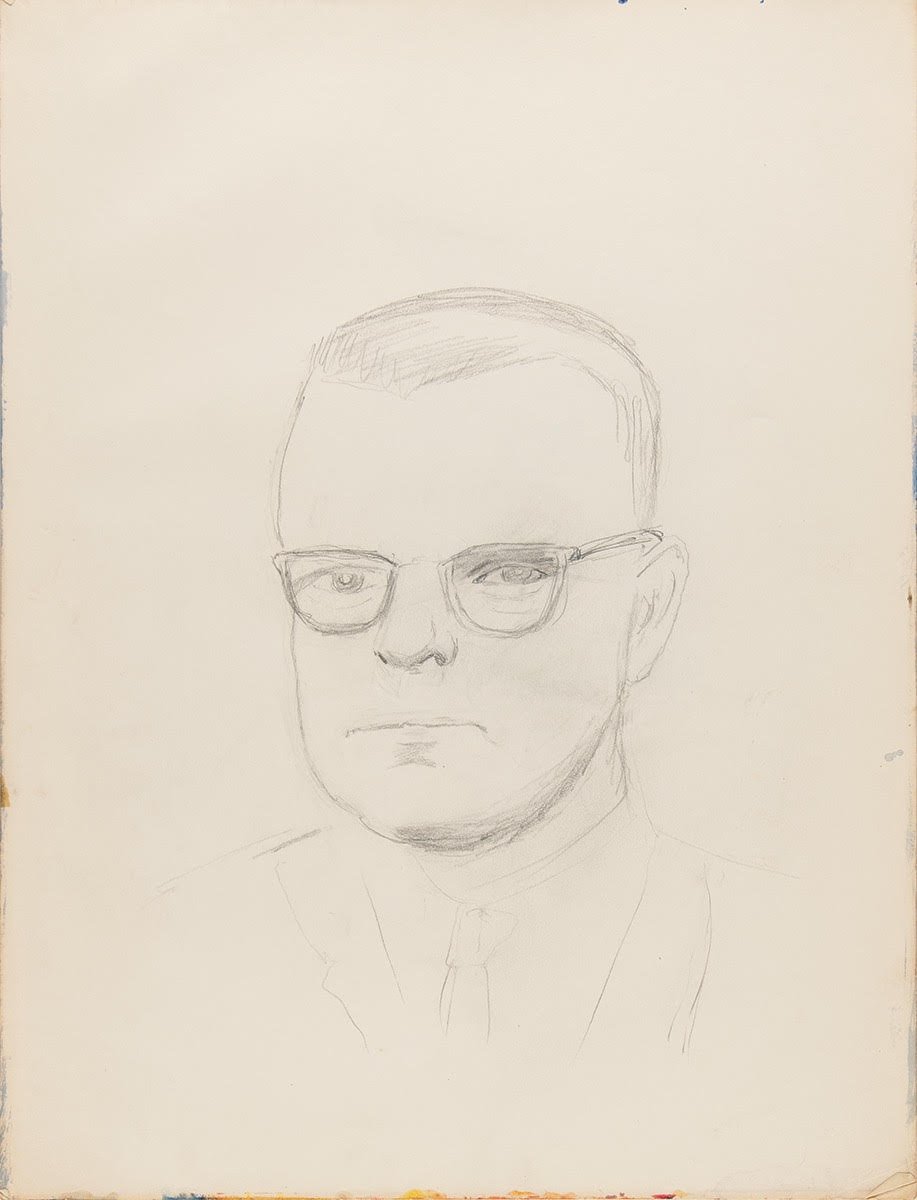

In a sketchbook she used in New York City and after are some exceptional individual pencil drawings. Truman Capote, looking just as he did when he hosted the Black and White Ball in 1966. A poignant memory of her time with Neuwirth is their signal for each other when one was in the rooms they shared at the Hotel Chelsea—when the lights are on, I’m there, I’m waiting for you. Both switches are on, and Edie has written “for Bobby” on the drawing. Sketches of a baby, of a mother and child, are even more moving.

Truman Capote by Edie Sedgwick

* *. *

After they married, Michael and Edie lived in a little apartment in Santa Barbara. He continued his studies at Santa Barbara City College, and she tried to stay clean, and away from her family ranch. But the horses were there. There, too, were stashes of pills, and she knew where. Edie remained under a doctor’s care, being prescribed barbiturates for sleeplessness and nervous conditions. One autumn night, she went to an art opening and party. She called Post, and asked him to meet her at the party. He did, and drove them both home. Edie took her prescribed pills when she got in. The following morning, he found her.

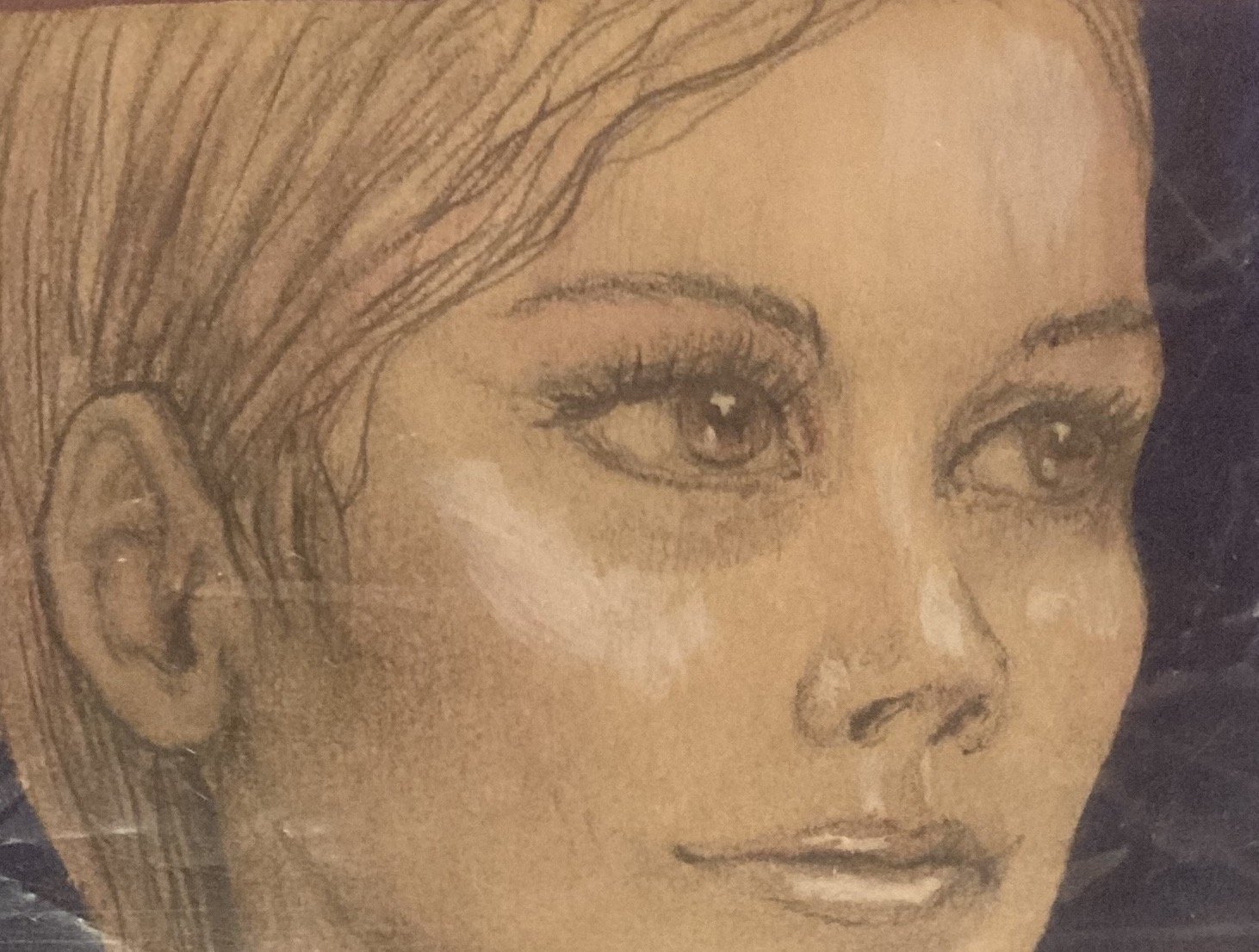

Edie Sedgwick, self-portrait, detail

Edie Sedgwick Post has long been known as a beautiful, young, laughing blank screen onto which fantasies could be projected. She’s the object of the longing gaze of Warhol in the films he constantly took of her, of songs by Bob Dylan that were purportedly inspired by her, of various male photographers’ camera lenses, of biographies that tell you as much if not more about the biographer than about Edie herself. How good to find out, finally, about the art she made for herself instead, as Edith, so long ago.

Selected works by Edie from the 1960s and 1970 were shown on Monday evening, November 14, at a private event at the Chelsea—where, once upon a time, she lived in Room 105. It has been almost fifty-one years to the day since her death; finally, her art is being publicly seen for the first time in conjunction with its sale by RR Auction of Amherst, New Hampshire and Boston. Present at the party were a sweep of New York City glitterati from her day to today: Danny Fields, Jay McInerney, John Stavros. Edie’s cousin Kyra Sedgwick wasn’t there, but her mother Patricia was. Everyone came to celebrate Edie’s life, and her own creativity. Libations were raised with two drinks the Chelsea created in honor of the night. Here, join us.

Edie ‘67

mezcal, raspberry, ginger, Lapsang Souchang tea, Gochujang honey

The Lost Weekend

Jamaican rum, Chartreuse, toasted coconut, snap pea

Still from the Andy Warhol movie “Afternoon,” showing Edie’s self-portrait on the wall of her apartment, 1965

All images reproduced here, and the quotations from Alice Sedgwick’s letters, are courtesy of and © RR Auction. Do not reproduce without permission.