Last week, I told you about an obscure early survival horror game inspired by the Alien film franchise and released onto a platform not typically associated with the genre. So I figured I may as well switch things up this time and tell you about an obscure early survival horror game inspired by the Alien film franchise and released onto a platform not typically associated with the genre. In space, no one can hear you repeat yourself.

That’s not to say that Silent Debuggers for TurboGrafx-16 plays anything at all like Alien 3 for Game Boy. It’s a first-person corridor shooter, for goodness’ sake, meaning that it was attempting to blaze multiple trails at once back in 1991. Figures it was developed by Data East, who seemingly never hesitated to get weird with a project. Bless them for that.

The game’s background is fed to you via an opening cutscene that both sets the mood with its slick old school anime presentation and calibrates your quality expectations for the English localization, which is a rocky one for sure. Stilted phrasing and bizarre grammatical errors abound in this tale of two hot shot space mercenaries (known as “debuggers”) who find more than they bargained for when they board a derelict space station in search of loot. Their job title comes to ironic fruition as they’re sealed in and forced to clear the sprawling structure of the insectoid monstrosities infesting it in order to escape. Worse, they need to do it before the hundred minute self-destruct timer ticks down. All in a day’s work for an ace debugger, right?

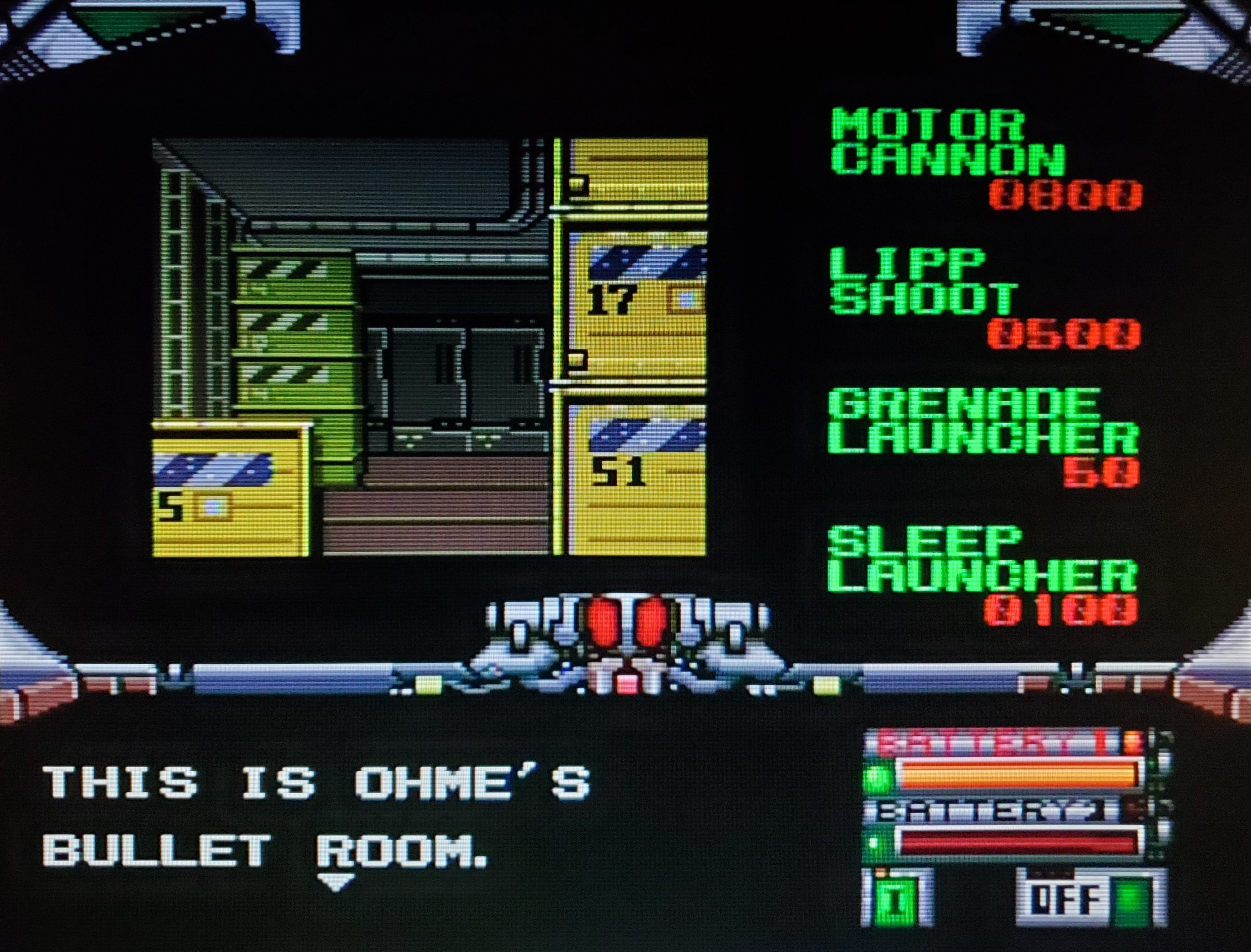

Of course, it’s up to you as the unseen and unnamed member of the duo to do all the actual combat. Your self-proclaimed “buddy” Leon spends the whole game parked in a comfy chair in the station’s central computer room, dispensing iffy advice and nuggets of background info relating to the mystery of where all these creepy monsters came from in the first place. He does do a couple useful things for you, though. First, speaking to him allows you to change your current weapon loadout. You can equip one each of the three primary and three secondary weapons to carry alongside your worthless starting pistol. Very rarely, he’ll offer you a new utility item, such as the vitally important jump unit that teleports you across long distances instantly in exchange for a hefty chunk of battery power. It’s worth checking in every now and then when you’re in the area just on the off chance he has some fresh tech for you.

Your general goal across all six stages is to destroy every monster present so you can move on. It sounds easy enough and would be if the developers hadn’t taken pains to saddle you with complications large and small. The most obvious is the time limit itself. A hundred minutes, no more. Likely less, in fact, since every death results in a five minute penalty and a nasty scolding from Leon. If you want to stay alive, you’ll need to make regular runs back to the station’s lone charging room to top off the battery power that doubles as your health and as ammunition for some of the stronger weapons. Other weapons use conventional bullets instead, but don’t expect that to cut down on your legwork, since you can still only reload them by retreating back to the armory. At least you have a reliable map at your disposal.

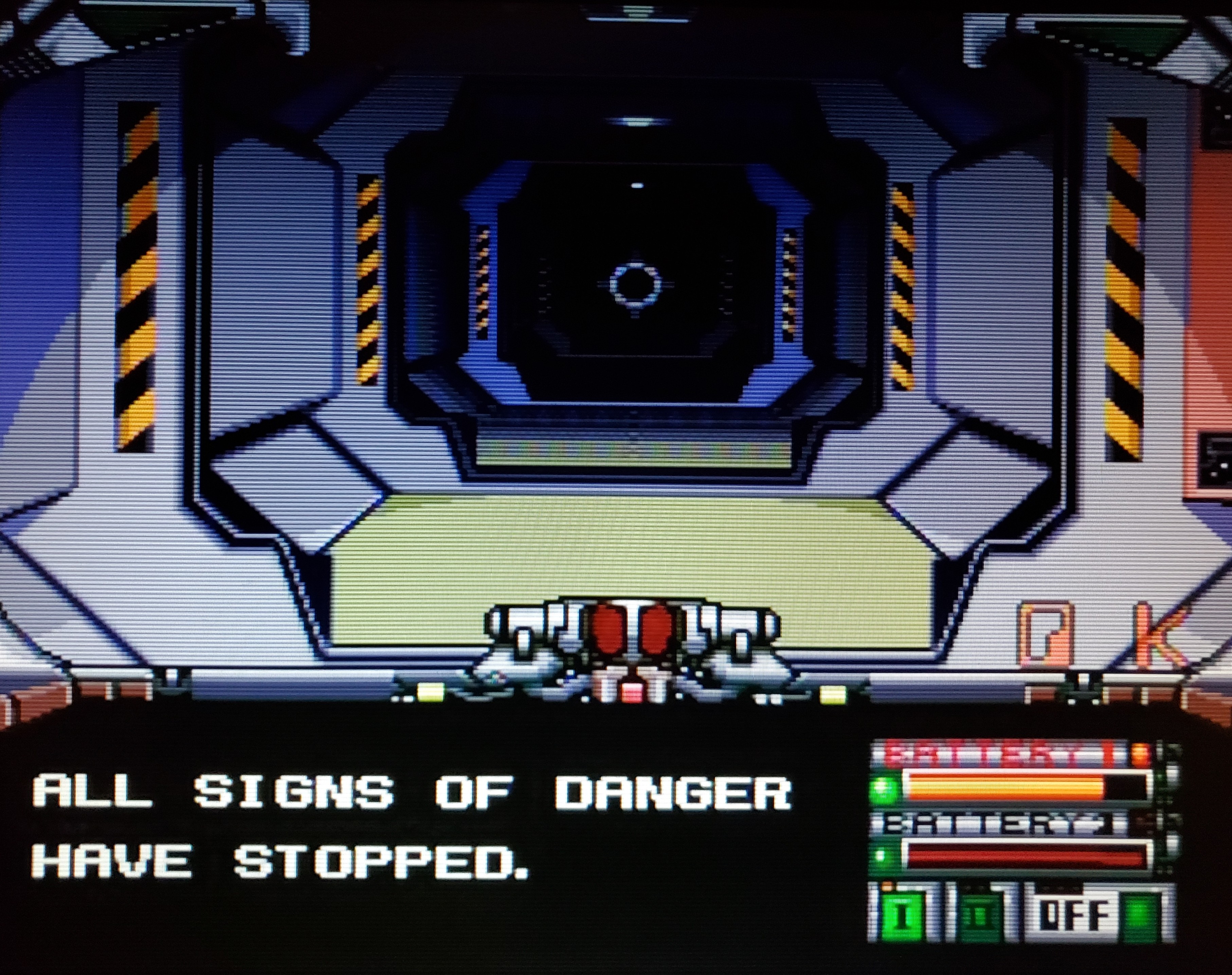

As soon as you’ve grown comfortable with managing your time, energy, and ammo, Silent Debuggers introduces yet another complicating factor in the form of a new monster type that launches dedicated attacks on the station’s far-flung facilities. If a single sector takes too much damage before you can get there and eliminate the bug assaulting it, it’ll shut down and remain inaccessible for the remainder of your playthrough. Yes, that includes the aforementioned charging room and armory, not to mention the power plant (forcing you to navigate the twisty halls in the dark) and the sensor array (which causes your handy portable monster detector to periodically crap out on you). I did mention that these resources never come back, right? And just when you’re starting to grow accustomed to this high stakes base defense component, there’s another hitch thrown your way. It’s relentless.

Silent Debuggers has a mixed reputation online, mainly due to how the relatively low number of distinct enemy types contributes to repetitive battles. That, and for how it implements Wizardry-style gridded maze movement instead of the smooth scrolling seen in later efforts like id’s Wolfenstein 3D and Doom. It’s barely a blip on the majority of TurboGrafx-16 ranking lists and although I certainly can’t argue that it’s a brilliant example of a first-person shooter, I did find it to be quite the solid survival horror romp. Its pattern of springing constant insidious surprises on the player continues all the way through to the sixth and final area, making for one masterful white knuckle ride. Losing your lights or sensors over an hour in is utterly brutal. Even if Leon’s gadgets can alleviate the pain a bit, they still take up precious inventory space and thus leave you at a disadvantage.

On top of being tense, immersive, and sporting respectable graphics and music for the format, Silent Debuggers is also more influential than I might have expected. The way your sensors utilize directional stereo sound to assist you in pinpointing hostile aliens was adopted and refined for Kenji Eno’s 1996 Saturn cult classic Enemy Zero. It’s a shame that this freaky little Data East experiment came and went with all the silence its name implies. I highly recommend it if you’re in the mood for something damn near diametrically opposed to the straightforward, arcadey fare the TG-16 is famous for.