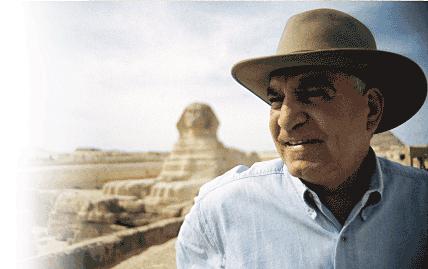

Archaeology’s answer to Carl Sagan has generated unprecedented interest in Egypt’s past and believes that science and history can “create love between countries.” In a world of increasing tensions, he says that mission is more important than ever.

By Kyle Cassidy

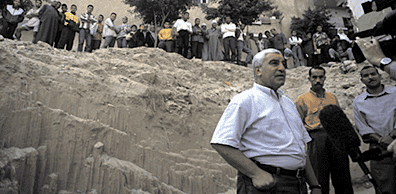

On a cool morning last November, several hundred residents of an otherwise quiet neighborhood in the northeast of Cairo gather around the rim of a vast pit, looking down intently at the flurry of activity below. Holding court atop a pile of stone slabs that make up the roof of a recently unearthed sixth-century tomb is Dr. Zahi Hawass G’83 Gr’87, director of the Giza Pyramids and Saqqara, undersecretary of the state for the Giza Monuments and the Bahariya Oasis, and one of the most famous men in Egypt. As workmen bring out baskets of sand through a narrow opening in the tomb, Hawass, surrounded by reporters and cameramen, patiently answers, in both English and Arabic, questions about the finds: the dates, the layout, the inhabitants, the damage suffered from local sewage.

Dr. Zahi, as he is known in Egypt, is doing what he does best—sharing his infectious fascination with Egyptian history and, not incidentally, using the media and technology to promote it to the outside world. Darling of the Discovery Channel, the History Channel, the Travel Channel, Fox, and CNN, as well National Geographic (which recently made him Explorer in Residence), Hawass describes his mission as “using archaeology and the magic of the pyramids and the history of Egypt to create love between countries.”

Bringing the old world to the new world, live, is something he’s done successfully on numerous occasions—most notably in 2000, when he invited Fox television to the Oasis of Bahariya to follow him as he opened some of the tombs of the Golden Mummies. Six million Americans tuned in. Called “the most important Egyptological find since the discovery of King Tut’s tomb,” the tombs at Bahariya have so far produced 250 gilded mummies from Greco-Roman times. The discovery made the cover of National Geographic and is the subject of a beautifully produced book by Hawass called Valley of the Golden Mummies [“Profiles,” November/December 2000]. He estimates that the cemetery, which covers four square miles, will eventually reveal 10,000 mummies over the course of a 50-year excavation.

Hawass shrugs off his mastery of the art of media relations. “Everybody works with the media,” he says, “it’s just a question of how well.” Asked if he enjoys being a celebrity, he answers, “I enjoy doing my job.” And part of that job is to be a celebrity—archaeology’s answer to Carl Sagan: equal parts statesman, salesman, scientist, teacher, magician, and showman. It isn’t possible to be around Zahi Hawass without being fascinated by whatever is currently fascinating him. Curiosity oozes from his pores, along with a deep and devoted love for the land of the Pharoahs.

“I Can’t Live in the Desert!”

Today it’s hard to imagine Hawass doing anything else, but in an interview last fall in Egypt and in the pages of his soon to be published autobiography

Secrets From the Sand, he portrays himself at 18 as restless and uncertain of his future. He thought he might like to be a lawyer, but a week reading law books changed his mind. He graduated from Cairo University in 1967 with a bachelor’s degree in Greek and Roman archaeology, and then took a job with the Egyptian Antiquities Department as an inpector of antiquities, still unsure this was the path he wanted to pursue.

He became even more doubtiful when he learned his assignment: Tuna el-Gebel, 250 kilometers south of Cairo, near the modern village of Hermopolis. In antiquity, Hermopolis (known by the ancient Egyptians as Khmunu) was an important city where a vast necropolis was built in honor of Thoth, the ibis-headed god of wisdom and writing. By the 1960s, though, it was exactly in the middle of nowhere, more than five hours from Cairo by train. Hawass had no desire to spend his 21st year living in a place with no electricity and only intermittent telephone service. He decided to change jobs.

The diplomatic corps sounded exciting. He easily passed the written exam, but the official at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs scoffed at the idea of an Egyptologist-diplomat during his oral examination. As he left the building, dejected and pondering his options, he bumped into the head of the antiquities department, Dr. Gamal Mokhtar, who demanded to know why he was not in Tuna el-Gebel, where he was supposed to be guarding thousands of mummified monkeys and birds.

“I can’t live in the desert!” protested Hawass. After being told in no uncertain terms that, if he didn’t, he would be permanently blacklisted from the antiquities department, Hawass forlornly packed his bags. The site was so remote that there were no roads for taxis, and he had to ride in on a donkey.

But his time at Tuna el-Gebel softened the young man’s loathing of sand dunes and isolation. He remembers spending hours in the necropolis, contemplating the tombs. This reflective solitude, interspersed with calls back to his friends in Cairo when the phones worked, had a satisfying impact on him. He traded the donkey for a bicycle, and learned much from other inspectors.

After two years, he asked for and received a transfer to Kom Abu Billo, where actual excavation was underway. Already an Egyptologist, he wanted to be an archaeologist as well. Located 70 kilometers northwest of Cairo, at the western edge of the Nile delta, the main site in Kom Abu Billo is a temple of Hathor, the goddess of joy, motherhood, and love. There, Hawass learned to dig. “Archaeology,” he says, “is not really books. Archaeology is the digging, the excavation, the discovery, and the thrill of the discovery. I am not the kind of person who can sit in an office wearing a necktie.”

Conditions at Kom Abu Billo were even more primitive than at Tuna el-Gebel, but the duties were more interesting. Hawass shared a tent with snakes and scorpions, and ate bread and onions and garlic every day, but he was uncovering history, not just reading about it. There was an undercurrent of excitement at the dig, which was turning up small pieces of gold, pottery, and statuary.

On a blisteringly hot afternoon in July of 1970, Hawass was going over some papers in his tent when the flap parted and a stream of hot white light poured in. Hag Mohammed, the dig’s conservator, said, “We have found something.”

Hawass quickly gathered some tools and followed Mohammed to the excavation, where they were working in a niche in the temple. The conservator pointed, and Hawass bent down to see a swath of blue cutting through the light brown Egyptian sand.

“Shall I dig it out?” Mohammed asked. He was well known among the workers as an excellent conservator.

“No, no,” Hawass answered. “I’ll do it.”

This was the first major find they’d made and his heart was being faster. Using his soft brush, Hawass began to clean the dust away. And as he did, he could tell that the streak of color was a statue, about 14 inches high, made of faience—a glazed silicate paste usually used in Egypt as a less expensive alternative to turquoise. But what the statue depicted was still a mystery. The faience was very delicate, and Hawass feared that it was in danger even from his soft brush, so he asked Hag Mohammed to treat it with chemicals to keep it from crumbling. When the chemicals had set, Hawass returned to the brush, and slowly the sand came away. Then, suddenly, his eyes came in contact with the eyes of Hathor, the goddess of love and beauty, revealed there in the sand, looking up at him with wisdom and wonder.

“There is no experience like that on Earth,” Hawass says, recalling that moment in the niche of the temple. “Do not say, I have a small job. If you give your passion to any job—if you are fixing cars or are a librarian or anything—you can make a small job the most important job on Earth, if you give it your passion. Love is not enough, because you can love anything. But passion is the most important thing, and I gave archaeology my passion that day.”

Protector of the Pyramids

In 1976, Hawass was appointed inspector of the pyramids at Giza. In 1987, following his return from earning his Ph.D. at Penn, he was promoted to director general of the Giza Pyramids and Saqqara and the Bahariya Oasis, the position he held until becoming undersecretary of the state in 1998.

Hawass has approached his job as chief protector of the pyramids and nearby sphinx with great zeal, moving to end practices such as guards accepting bribes in lieu of admission fees, or to let tourists climb the monuments or spend the night in them. Following a series of thefts at Giza in 1976, Hawass recovered the stolen artifacts and helped put the thieves in jail (where they remain today). He has also implemented procedures to preserve both the dignity and the physical integrity of the pyramids.

Hawass has issued a site management and conservation plan that calls for the removal of all modern buildings on the Giza plateau, the relocation of camel drivers to a more remote area, and elimination of motor-vehicle traffic around the pyramids. On a wider scale, his plan contemplates the curtailing of excavation in Upper Egypt (to the south, up the north-flowing Nile), where desert sands have protected monuments for thousands of years and will most likely continue to do so. The plan encourages excavation in Lower Egypt, where the Nile meets the Mediterranean, and where rising water tables and increased agriculture pose a threat to buried artifacts.

Perhaps the greatest threat, though, is the pyramids’ very popularity. The sheer weight of millions upon millions of tourists—fingers touching surfaces, feet upon stairs, even breath (on average, each person inside the tomb leaves behind 20 grams of water)—are having an impact, not to mention damage caused by automobiles, roads, plumbing, camels, and building construction. All these serve to destroy, little by little, that which was thought indestructible. “Every day, four or five thousand tourists visit the Valley of the Kings and every one of them visits the Tomb of Tutankhamun,” says Hawass. “If we do not act now, some of the Egyptian monuments will be gone in less than 100 years.”

From Cobras to Cockroaches

Hawass has made his share of enemies. In 1980, the same year he was named chief inspector of the pyramids, he received a diploma in Egyptology from Cairo University, but he came under fire because he did not have a doctoral degree. Deciding to remedy that lack, he begain sending out applications and ultimately chose to get his Ph.D. at Penn, “because it was the only school with good programs in both archaeology and philology,” he says.

The man who had shared his bed with cobras and scorpions found the local fauna in West Philadelphia a little trying. “I lived at 43rd and Walnut for seven years; directly upstairs from the laundromat. It was terrible. I wasn’t home very much and cockroaches would come up into my apartment from the laundromat. It was awful. I spent all my time at the University Museum [of Archaeology and Anthropology]. Basically, I lived there. The guards all knew me by name.”

Studying under Dr. David O’Connor, now emeritus professor of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, who taught archaeology, and Dr. David Silverman, professor of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, who taught philology, Hawass finished his coursework in three and a half years and spent another three writing his two-volume dissertation on the funery cult of Khufu (called Cheops by the Greeks), the pharoah who built the largest of the great pyramids. His dissertation also accurately predicted the location of the tombs of the pyramid builders, which would not be discovered for another 15 years.

“Zahi really broke the mold in coming to America to get his doctorate,” says Silverman. “He took a lot of risks leaving behind a job for so long—there’s always a risk that it won’t be there when you come back.” He adds, “A lot of what he learned here are things like site management, which you can see now in his work, but he also started lecturing as part of our program and quickly became our most popular speaker. He discovered how good he was at that. In many ways he was really the right person in the right job at the right time.”

Aside from his humble accommodations, Hawass was hardly the average graduate student. There was a respected position waiting for him back in Cairo, and, while in the U.S., he became close friends with Abdel Raouf el-Reedy, Egypt’s ambassador to the United States, who introduced him to American politicians and celebrities, all of whom were fascinated by the 34-year old’s glowing tales of his homeland. The lectures he gave for the University Museum’s education department throughout the United States were well-attended and enthusisatically received, giving Hawass his first taste of public stardom.

Doctorate in hand, Hawass returned to Egypt and attacked his old job with gusto, winning loyal followers around the world—but at times ruffling the feathers of colleagues by his willingness to sensationalize. “I got a letter from a young boy, 11 years old, who had watched the Fox special, the first one,” he says. “And he wrote to me that he has now decided to become an archaeologist because I had touched a special place in his heart. This show touched his heart. In our field, there are many jealous people. They say, ‘How could you do a special like this?’ What was wrong? I did not hurt the antiquities. But before that show everybody was talking about the pyramids in terms of Atlantis, lost civilizations—there was a big attack against me by New Age people who thought I was hiding things. But that show stopped all of this. It made people realize that talking about lost civilizations did not address this, but archaeology did address it.”

Apart from professional jealousies, Hawass is also plagued from time to time by what he calls “pyramidiots,” who hold a variety of bizarre beliefs about the pyramids’ origins and special properties. Among the most notable examples was a rumor circulating on the Internet in 1999 that there was a secret passage from his office restroom leading to hidden chambers beneath the pyramids and that a living body had been discovered in Menkaure, the smallest of the Great Pyramids. Hawass often meets these people head on, inviting skeptics to tap on the walls of his bathroom and allowing them to search the pyramids for secret chambers. He has also performed experiments to test unusual claims—such as that the mystical proportions of the pyramids keep meat (or human remains) in a state of perfect preservation. Hawass left one pound of beef in the king’s chamber of the great pyramid and a second on a shelf in his office, noting that they decomposed at the same rate, and quickly.

Real Gold: Information

Even those who doubt the involvement of extraterrestrials or lost civilizations have been theorizing about the building of the pyramids for millennia. Since April 1990—when a horse being ridden by an American tourist tripped over part of a wall exposed by wind erosion, leading to the discovery of the tombs of the people who actually did build the pyramids—Hawass has begun to lay much of the speculation about their origin to rest and replace it with evidence about the daily lives of the common people who performed the work.

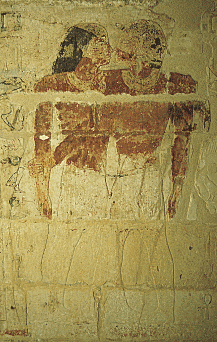

The tombs of the pyramid builders are formed in two layers that wrap along the eastern side of the Giza plateau, near the Sphinx. Laborers are buried on the lower level, their backs and bones showing great signs of stress from years of heavy lifting. On the upper level are buried skilled craftsmen with more elaborate tombs, rich with drawings and hieroglyphs. One contains a juicy, media-friendly curse warning that tomb robbers will be attacked by a litany of beasts, including lions, hippopotami, and crocodiles. Curses and gold interest the public, and Hawass can use them to hook people, and to tell them about the real gold in these tombs: information. “The discovery of King Tut’s tomb gave people the idea that tombs are full of gold,” he says, “but this discovery is significant because it teaches us about the common people, who represented about 80 percent of the country.”

The popular image of the pyramids’ construction—thousands of slaves under the lash, worked to their deaths to satisfy the ego of a tyrant—is clearly recognizable in the account of the Greek historian Herodotus, who visited the pyramids in 500 BC (when they were already 2,000 years old):

Kheops, who was the … king, brought the people to utter misery. For first he closed all the temples, so that no one could sacrifice there; and next, he compelled all the Egyptians to work for him. To some, he assigned the task of dragging stones from the quarries in the Arabian mountains to the Nil; and after the stones were ferried across the river in boats, he organized others to receive and drag them to the mountains called Libyan. They worked in gangs of a hundred thousand men, each gang for three months. For ten years the people wore themselves out…. The pyramid itself was twenty years in the making. Its base is square, each side eight hundred feet long, and its height is the same; the whole is of stone polished and most exactly fitted; there is no block of less than thirty feet in length.”

Many of Hawass’ recent findings contradict such tales. “We know now that there were about 20,000 workmen involved with the construction of the great pyramid,” he says. “We know that they were divided into gangs, and that each gang consisted of 1,000 workmen. Each gang had a name, each gang had an overseer. They divided each gang into groups; each group was 200. They had names—‘great ones,’ ‘green ones’—and they divided the groups of 200 into small units of 10 to 20 workmen, who had names like ‘perfection.’ And from this we can learn about the organization of building the pyramids, which is more important than building the pyramids.”

Hawass also believes that the tombs were not built by slaves, and that there was no antipathy for the king. They built out of love for their ruler, working only in the four months when the Nile was flooding and farming was impossible. “Every house,” he says, “would give something. Grain or labor. They did it out of love for their king.”

“We Can Make Love Appear”

Tourism to Egypt has been down significantly since September 11 and the worsening conditions in the Middle East. At Saqqara, where pyramid-building began with King Djoser’s step-pyramid, 500 people come to look on a day when 3,000 had come through a year ago. Now, more than ever, Hawass feels his mission is to be the Egyptologist-diplomat that the foreign service scoffed at when he was a young man.

“I am an unofficial ambassador for Egypt,” he says. “I lecture all over the world, in every major city. I have made friends of Egypt everywhere. You have all these people who give their passion to Egypt, and then they come here and see that the Egyptians are nice people.

“That is why I feel that my mission is very important. That using archaeology and the magic of the pyramids and the history of my country, that we can really make love appear between countries. And that’s very important. Love between people cannot come from government or from speeches, but it can come through science and history.”

Hawass is quick to point out the differences between governments and citizens, and he realizes well the differences between politics and people. “Egyptians are nice people, they love Americans very much,” he says. “Sometimes we need to tell the press in Egypt, that when someone is writing something against America, they need to emphasize that it doesn’t mean that we are against the Americans, but against the American foreign policy.”

Hawass’s office—modest for an undersecretary of the state—is a maelstrom of activity; people bustle in and out, carrying papers, files. Hawass himself is constantly flanked by at least one assistant. Often he is speaking on two telephones at once in a combination of English and Arabic, while signing papers, writing notes, and dispatching people to various sites. He teaches now at both Cairo University and UCLA, and his latest book, Secrets from the Sand, is due out this year. On his walls, mementos include photographs of himself and Princess Diana, Chelsea and Hillary Clinton, Brooke Shields, Laura Bush, and many others. His personal Web site (www.guardians.net/hawass) attests to the range of his activities, both public relations and scholarly, from the latest news of excavations at Giza to showing former President Bill Clinton around the pyramids in January.

Back at the excavation in suburban Cairo,Hawass continues to answer questions from his perch on top of the sixth-century tomb. Beneath him, workers pass out rubber baskets of dirt. At the top of the excavation pit a photographer from Reuters is taking photographs of a local shopkeeper surrounded by cages of ducks and rabbits. Men, women, and children sit in the sand and stare down at the swirl of activity, the exact center of which is Zahi Hawass’ love of Egypt, which began on that hot summer day in 1970 when he first fell under the spell of Hathor.

“This proves two things which I have always said,” he tells the assembled media. “First, that we have only uncovered 30 percent of the monuments—another 70 percent still lie buried. And secondly, you never know what the sands of the desert will reveal.”

Kyle Cassidy is a photographer and writer who works for the Annenberg School for Communication.