Why Iran may feel less restrained in nuclear decision-making now

By John Ghazvinian | October 26, 2023

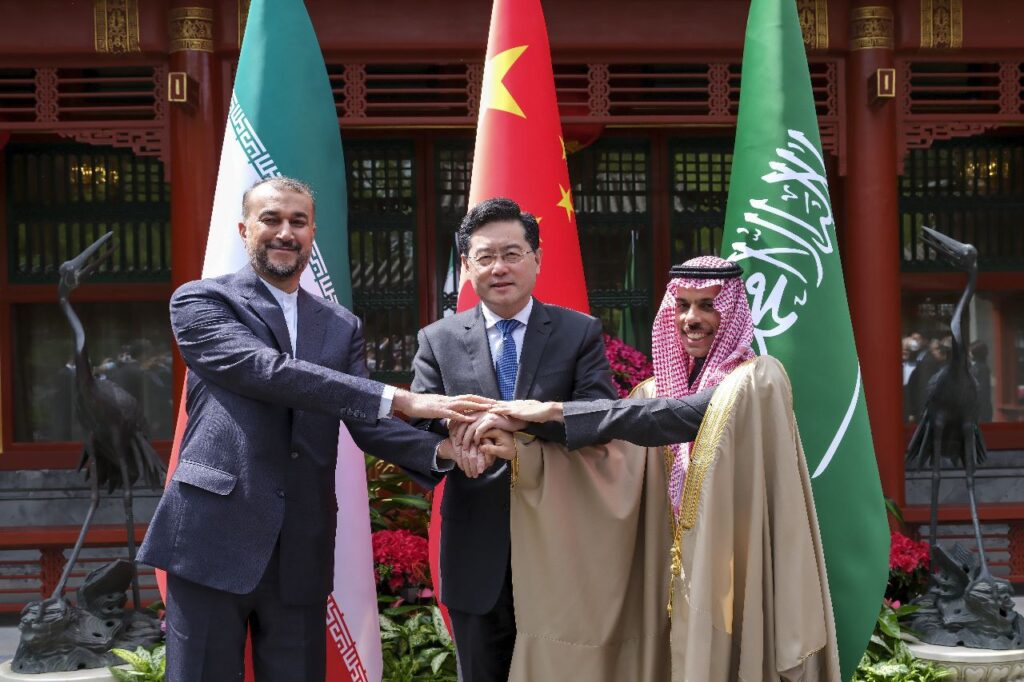

Foreign ministers of Iran, China, and Saudi Arabia meet in Beijing on April 6, 2023 to finalize a China-brokered Saudi-Iran deal struck in March 2023. (Photo: Chinese Foreign Ministry)

Foreign ministers of Iran, China, and Saudi Arabia meet in Beijing on April 6, 2023 to finalize a China-brokered Saudi-Iran deal struck in March 2023. (Photo: Chinese Foreign Ministry)

Since the start of the conflict in Ukraine in February 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin has made a series of statements implying that Russia might be compelled to use tactical nuclear weapons to defend its interests in the region. This has caused concern among decision-makers in the West, who are understandably wary of the possibility of all-out nuclear conflict at Europe’s doorstep. However, some analysts have also raised a secondary concern: If Russia gets away with even a limited use of nuclear brinkmanship without consequence, other countries might feel less restrained about developing their own nuclear weapons, starting with Iran, which has already been deprived of any incentive to continue complying with the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), also known as the Iran nuclear deal.

This concern, however, rests on a faulty set of assumptions and ignores the long-term trends at work, which have far greater impact on Tehran’s nuclear decision-making than the immediate implications of the conflict in Ukraine. For starters, Iran has historically accelerated, slowed, and suspended its nuclear program. These actions were not based on what Iran thought it could “get away with,” but on Iranian decision-makers’ perceptions about the usefulness of its nuclear program to securing the country’s territorial sovereignty and the regime’s survival. This has been true since at least the late 1950s, when Iran’s former monarch, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, ordered the development of an indigenous program of nuclear research and enrichment, despite his close relationship with the United States. The shah calculated then—as the Islamic Republic has calculated since—that some measure of nuclear capability (if not an actual bomb) was an important guarantor of the country’s technological advancement as well as its prestige and influence in the region.

Little has changed in the past few decades. Iran’s leaders have still not made the decision to “race for a bomb”—despite having nearly all the necessary technological capacity to do so. For the most part, this has been a political decision, though there are also important religious restrictions at work. Iran’s continuing calculation is that it has more to gain from cooperating within the legalistic international framework of the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) than it does from taking the North Korean path of flouting it by developing a bomb.

Iran’s restraint, however, may now be limited. And it may have more to do with Washington’s policy posture than with the war in Ukraine. In 2003, when North Korea announced it was leaving the NPT and rapidly developed a nuclear weapon, several hardline Iranian lawmakers—indignant at what they felt was an outsized US preoccupation with Iran—could be heard suggesting that perhaps the time had come for Iran to do the same. But these voices were swiftly silenced: Iran’s leadership believed that it had much more to gain from allowing the negotiating process with the P5+1 (as the official party negotiating with Iran has come to be known and that comprises China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States) to take its course and find a compromise solution to its nuclear dispute with Washington.

Today, things look very different. Following the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the JCPOA in 2018, and the subsequent campaign of “maximum pressure” against Iran—including the killing of the country’s top general and the imposition of hundreds of suffocating economic sanctions—Iran now feels it has little to lose. It has not seen any serious diplomatic efforts on the JCPOA front from Washington in months, and its own domestic political turmoil following the death of Mahsa Amini—which has seen the most serious public protests in a generation, accompanied by a chorus of condemnation from the West—have left Iran’s leaders believing there is little point left in continuing to discuss their nuclear program with Western powers. All this contributes to an atmosphere in which the North Korea option might seem more appealing than ever.

And yet, the option of developing a bomb is still largely taboo in Iran. In recent months, several hardline voices have again suggested that Iran could cease its cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency, or even withdraw from the NPT completely. But these suggestions have once again been shot down. It appears that as long as Iran’s current Supreme Leader, the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is in power, Iran will remain in the NPT and not pursue a bomb. But Khamenei is 83 years old and what may come after his rule is anybody’s guess. Khamenei has consistently used his position as the country’s most revered religious authority to insist that nuclear weapons are a sin against God and that the Islamic Republic will never seek to possess them. But if, as many fear, a post-Khamenei Iran drifts toward more autocratic military rule, centered on the power of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, this longstanding religious injunction against nuclear weapons might be called into question.

Then, there is the regional dimension. In March 2023, Saudi Arabia and Iran surprised the world by announcing an intention to resume diplomatic relations—ruptured in 2016—in a deal ostensibly brokered by China. This volte-face could have significant implications for the political dynamics in the Middle East, including for Iran’s nuclear decision-making. There is still much we don’t know about the Iran-Saudi deal and the direction of their relations in the short to medium term. But it is not far-fetched to imagine a future in which tensions between these two regional competitors are reduced significantly and sustainably—perhaps even to the point at which Iran sees some benefit in engaging more constructively with the US-led bloc in the Middle East.

The war in Ukraine could impact these existing trends and challenges, but not necessarily in the ways we might think. First, although Iran is generally viewed by Western countries as a proliferation risk, the Middle Eastern country has its own reasons to fear a nuclear conflict at its own doorstep. For years, Iran has advocated for the creation of a Middle East Nuclear Weapons Free Zone—a proposal that has so far been a nonstarter in international negotiations, at least in part due to Israel’s existing, albeit undeclared, nuclear weapons arsenal. When asked about its nuclear program, Iran has long maintained that it has no desire for acquiring nuclear weapons. Iran’s leaders have described such weapons as unnecessary and outdated relic of the 20th century—and that countries that do possess them ultimately gain little to no real tactical benefit from them.[1] If Russia continues to struggle in its war against Ukraine, despite possessing an arsenal of about 4,500 nuclear weapons, this only helps to bolster Iran’s narrative.

Ultimately, the largest impact of the war on Iran’s nuclear decision-making might be the striking realignment of alliances and priorities in the Middle East and beyond—whether it takes the form of Iranian détente with Saudi Arabia, improved Chinese-Russian ties, or closer Iranian-Russian cooperation on sanctions evasion and military hardware. These potential shifts and realignments, taken together, might well reconfigure the strategic horizon for Iran in a way that impacts its nuclear dossier. At least for now, Iran is likely to continue making decisions about its nuclear program based on the traditional factors of national interest, territorial sovereignty, and regime survival that have always guided it. But until when?

Editor’s note: The statements made and views expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the author. This article is a product of a Perry World House workshop on “The Future of Nuclear Weapons, Statecraft, and Deterrence after Ukraine,” which took place on April 4, 2023. This workshop was made possible in part by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Notes

[1] John Ghazvinian, America and Iran: A history, 1720 to the present (Knopf, 2020), p.472.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

The 2015 JCPOA Agreement was signed between Iran and 7 partners and not 6.

Indeed, the seven partners were: US, UK, FR, DE, RU, CN and the EU-European Union.