Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

Benjamin Franklin is having a moment. For decades he has hovered on the periphery of popular representations of the American founding. This month, however, Franklin gets marquee billing as the focus of a four-hour biographical documentary from filmmaker Ken Burns (premiering Monday on PBS), plus a new book from writer Michael Meyer on the afterlife of Franklin’s philanthropic efforts. This follows on the heels of a February announcement that Michael Douglas will play Franklin in an upcoming Apple TV+ limited series based on his life.

It is, in some ways, odd that Franklin has not gotten the same level of attention as his compatriots during the flourishing of “Founders Chic,” a two-decade-old trend in American popular history in which biographers, writers, and musical theater impresarios have celebrated the major figures of the Revolution as an 18th century “greatest generation” that nobly led the United States to independence and set it on a path to freedom. Franklin was a generation older than many of the others involved in the founding, a fact that has affected his portrayals in this recent wave of Founder-centric pop culture. In the 1969 Broadway musical 1776, a Founders Chic precursor, Franklin is the avuncular sidekick to John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, dispensing one-liners and the occasional timely advice to keep independence moving. In HBO’s 2008 miniseries John Adams, Franklin, no longer a friendly father figure, is instead portrayed by Tom Wilkinson as a lecherous schemer who preys on the women of Paris and undercuts Adams’ efforts at American diplomacy. Lin-Manuel Miranda cut a Franklin number from Hamilton (2015), but later released it as a stand-alone track performed by the Decemberists. In the voice of Franklin, lead singer Colin Meloy recounts his career accomplishments, leading into a repeated chorus, “Do you know who the f*** I am?” Given the song’s message, it’s a touch ironic that Miranda so easily sidelined Franklin, but that’s how things have gone for the Philadelphian, who has so often seemed like an outlier in the story of the founding.

Why has the spotlight now swung to Franklin? One easy answer is that he’s always seemed to be the Founding Father most likely to enjoy modern American life. One can readily envision Franklin engaging in debates via blog, Twitter feed, or TikTok. That modern sensibility makes him a useful subject for humor. Unlike most of the other Founders, he was truly self-made. His family was not destitute while he grew up in Boston, but he was the 15th of 17 children, and the youngest son. He worked hard wherever he went, from his brother’s printing office in Boston to ones in Philadelphia and London. He cultivated connections with important men in each place. And he sought to project precisely that image to the world. “In order to secure my Credit and Character as a Tradesman,” he wrote in his autobiography, “I took care not only to be in Reality Industrious and frugal, but to avoid all Appearances of the Contrary.” The fact that he rose from a position as a youngest son of a candle- and soap-maker to become a wealthy businessman, renowned scientist, political leader, and diplomat is legitimately impressive, but it also makes him a Founder particularly suited to contemporary American hustle culture.

He also appears accessible and human in his writings. Jefferson, by contrast, is practically inscrutable; Washington cultivated during his own lifetime an arm’s-length distance from the general public; John Adams—well, the man did many great things, but he was prickly. Franklin, in the writings he left behind, appears warm and fun-loving. And he wore his flaws lightly—the contradictions between his accomplishments and his failures are right in the open, sometimes thanks to Franklin himself. In his most extensive piece of writing, his autobiography, Franklin recounts both his triumphs and tribulations. He outsmarts his brother James to escape his indenture, but then arrives in Philadelphia with barely enough money to feed himself. After wandering the streets with “three great Puffy Rolls”—one to eat and one under each arm—he enters a Quaker meeting house and promptly falls asleep. He outlines an attempt at self-discipline by cultivating virtues such as temperance, frugality, and justice. But upon informing his friends about the plan, they insisted that he add one more: humility. He interprets that to mean that he should “imitate Jesus and Socrates.”

The biographical detail that he considered his own greatest error in life has resonated all the more in recent years. In 1736, Franklin’s 4-year-old son Francis died of smallpox, a disease to which nearly everyone in the 18th century world was exposed. The death could have been prevented. As Franklin reports, “I long regretted bitterly and still regret that I had not given it to him by Inoculation,” a poignant memory that has resurfaced numerous times in conversations around vaccination generated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Burns film goes to great lengths to capture these contradictory elements: the consummate achiever and the self-aware critic. Because Franklin himself set the stage for that perception, the film offers a largely conventional, though nuanced, narrative of his life. Over the past 30 years, Ken Burns has become a documentarian of American life against whom others measure themselves. He has usually focused on broader topics or concepts—the Civil War, baseball, jazz—so a biographical documentary is a bit of a turn for him. Many of the elements common to a Burns production are present in this one: An omniscient narrator carries the story, punctuated by voice actors reading the correspondence and writing of Franklin and his contemporaries, including Mandy Patinkin as Franklin himself. (I won’t spoil who voices John Adams, but you can click here to find out, if you can’t wait.) A somewhat more diverse crop of scholars than in Burns’ earlier work offers thoughts, but standby talking heads like Walter Isaacson, H.W. Brands, and Clay Jenkinson get the bulk of the airtime.

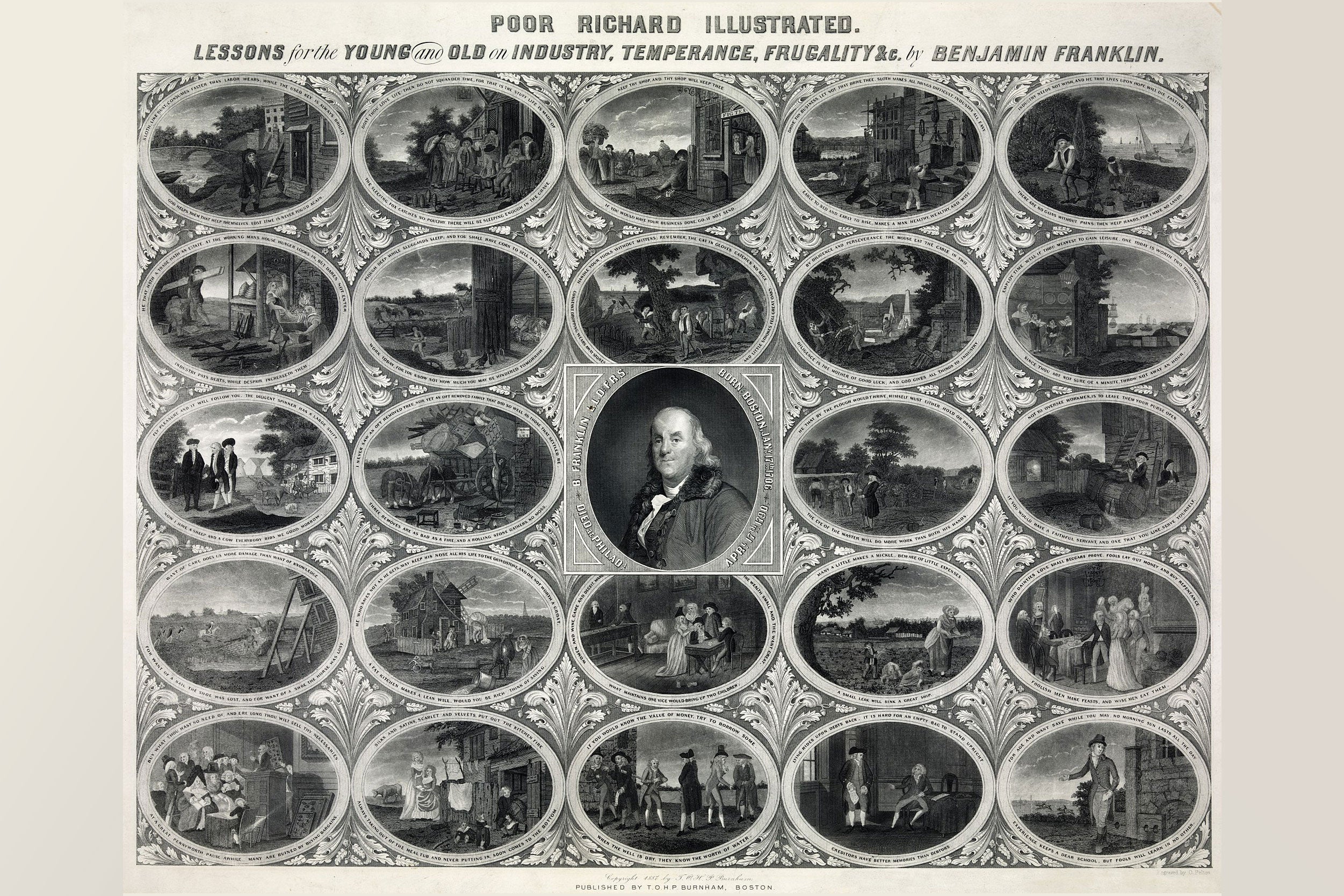

The two episodes are a useful primer on Franklin’s life for those unfamiliar, in particular because it delves into the history behind some of the myths and legends about him. We learn, for instance, about his pseudonymous writing, beginning with his turn as Silence Dogood while still a teenage apprentice and continuing as almanac author “Richard Saunders,” usually known as Poor Richard. His experiments with electricity—the iconic flying of a kite in a thunderstorm—advanced both scientific understanding and his international career. His role as a politician in Pennsylvania and London carries across the two episodes, marked by the rupture that ended his imperial ambitions and made him a leader of the American cause. The second episode focuses considerable attention on his wartime diplomacy in France (over his relatively smaller contributions to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution), emphasizing the importance of the alliance for American victory in the Revolutionary War.

It’s clear that Burns as well as the scholars he interviews hold Franklin in high regard. Biographer Stacy Schiff, whose 2005 book is the basis for the forthcoming Michael Douglas miniseries, describes Franklin as simultaneously “approachable” and “superhuman,” a sentiment shared by many of the guests. The film introduces the audience to newer scholarly interpretations on the subjects of Franklin’s relationship with his wife Deborah and son William. Long derided as a woman of low intelligence, based largely on the varying spelling in her letters, Deborah was in fact a key partner for Benjamin. She helped run his printing office and managed the family’s affairs during his lengthy absences. Then there is William. Until 1775, both father and son dreamed that they would catapult the younger man into the highest echelons of imperial society, with William’s service as royal governor of New Jersey as the launchpad. But when fighting between Britain and the colonies began, Benjamin took the side of the colonists and William became a leader of the American Loyalists. Despite attempts to reopen dialogue after the war, Benjamin refused to reconcile because of what he believed was a personal betrayal.

The filmmakers also delve deeply into Franklin’s experience with slavery. This is an area where a shift in popular understanding is much needed. Other than historian David Waldstreicher, in his 2004 book Runaway America, scholars have offered little attention to Franklin’s ownership of numerous people of African descent. Burns’ talking head scholars tread a careful line throughout the discussion of Franklin’s life. The documentary never shies from accepting Franklin’s involvement; instead, slavery shows up within the first minutes of the first episode. Scholars of slavery such as Erica Armstrong Dunbar and Christopher Brown contextualize Franklin’s position. During his lifetime, Franklin owned five or six people, none of whom he freed. On top of that, he used his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, as a forum for others to buy and sell enslaved people and track runaways. In the final minutes of the second episode, the documentary addresses Franklin’s leadership of an anti-slavery society and his final public statements on the topic, a petition to Congress on behalf of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and a satirical essay lampooning a Georgia senator who defended slavery in response. Those actions clearly represented a shift away from his lifelong acceptance of slavery, something the film effectively conveys.

In elevating Franklin back onto the stage, Burns recaptures some of the attention and adulation Franklin received in the early United States. His autobiography—published initially in France, then England and the United States just a few years after his death—came to be a model for how American children should aspire to act. Appearing in over a hundred editions before the Civil War, the “private memoirs” of Franklin depict his emergence from obscurity in Boston to business success in Philadelphia. Because only the first portion of the autobiography, covering Franklin’s youth up to about the age of 25, was available in the first decades after his death, publishers usually appended a biography covering the rest of his life. These 19th century Franklin memoirs-biographies framed him as a role model, emphasizing precisely the same qualities as … the Ken Burns documentary.

Breaking new ground on Franklin, then, is a difficult matter. What portion of his life has not been explored in some way? It turns out that his afterlife is available for a new perspective. Franklin was prolific during his lifetime in the creation of philanthropic projects aimed at “improving” society. Philadelphia still boasts many of them today: the Library Company, the American Philosophical Society, and the University of Pennsylvania are the most well-known, but Franklin also created a fire company, founded a hospital, and more. At the end of his life, Franklin added one more project, through his will. Among his bequests, he left 1,000 pounds each to the towns of Boston and Philadelphia to create a fund for the benefit of young tradesmen. As laid out in a 1789 codicil to his last will and testament, Franklin gave the money to the towns to be loaned out at 5 percent interest to married men under the age of 25 who were establishing themselves in a trade. By Franklin’s calculations, the repayments of principal and interest from loan recipients would allow the fund to grow over time. After 100 years, the towns could each take money out of the fund for “public works,” and continue lending out the remainder to early-career tradesmen for another century. At the close of 200 years—that is, in 1990—Franklin directed that the fund be split between the city and the state governments, to spend as they pleased.

Meyer traces the divergent paths the funds took in the two Eastern ports over those ensuing centuries. Because the overall narrative of Benjamin Franklin’s Last Bet concerns the 19th and 20th centuries, we get to see an image of Franklin refracted through the lens of the American history that followed. “Every generation,” Meyer intones, “discovers Franklin for themselves.” Among others, Franklin inspired tradesmen in the early years of the United States, in particular printers and other workers in the printing trades, Franklin’s first career. Franklin and his bequest inspired Andrew Carnegie, another up-from-nothing American businessman, who like Franklin turned his fortune (which dwarfed what Franklin had amassed) to philanthropy.

In Boston, management of the fund went reasonably well, helping over a hundred tradesmen in its first few decades, before industrialization and mechanization began to make the careers that Franklin envisioned obsolete. Boston’s fund managers adjusted with the times, in part by shifting their support from direct help for businesses to providing funds for mortgages, for example. By the 1830s, the fund had come into the control of professional money managers, who chose to invest the bulk of the fund’s accounts with banks and insurance companies, preserving Franklin’s desire to grow the fund, but doing so at the expense of early-career workers. Philadelphia could not even accomplish that much. Like the managers in Boston, the mid-Atlantic managers began to offer less and less support to workers as the 19th century ground on. Yet they also failed to invest the money in any meaningful way, so that the available funds began to dwindle rather than grow over the decades. By 1890, with one century elapsed in the gift’s timeline, Boston was close to on track to Franklin’s projections, and Philadelphia far off. Each city engaged in a lengthy debate to determine how to spend the funds that could be withdrawn. Each ended up investing in something educational. Boston’s trustees founded the Franklin Union in 1906, which has evolved into the Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology. Philadelphia used the money to seed the Franklin Institute, now a significant science and technology museum. In the 1990s, with the funds now fully available to the state and city governments, officials spread the money even further, using money in Boston to fund medical students and in Philadelphia to create a scholarship fund for students entering trades, as well as funding for the Franklin Institute and community foundations.

The winding path that Americans took to honor Franklin’s legacy through his bequest offers a fair object lesson in the process of how “every generation rediscovers Franklin.” As much as any other prominent figure from the Revolutionary era, Franklin worked until his dying day to craft his image, reputation, and legacy for succeeding generations. The dividends of that effort are apparent in the many Philadelphia institutions connected to him, not to mention the eagerness of others to claim a connection. They show up in the continued attention to his autobiography and other original writings, and in the popular history that translates his work for a broad audience. And they appear even in the ways our attention waxes, wanes, and diverges from Franklin’s stated wishes. H.W. Brands dubbed him the “First American” for good reason: Franklin was constantly striving, ever seeking to improve, and fully cognizant of his own deficiencies. Not to mention someone who would, if he ever had the chance, surely attract millions of followers on TikTok.