What follows is an account of the modernist-fundamentalist controversy that used to be on the First Presbyterian Church (NYC) website. Thanks to the Wayback Machine, you can still find it. But now you have Old Life’s Cloud. You’re welcome.

On curious aspect of this piece is how central Harry Emerson Fosdick is to First Presbyterian’s understanding of the controversy. That editorial decision allows the First Church to end the story with a kind of “my bad.” “Yes, we got a little carried away with modernism. But no apologies to conservatives like Machen who the Presbyterian bureaucratic bus ran over.”

Another is the importance of Charles Briggs. B. B. Warfield was on to something. But by the 1890s strict Presbyterianism (doctrine or church polity) was on short supply any where in the trans-Atlantic world.

______________

The Fundamentalist / Modernist Conflict

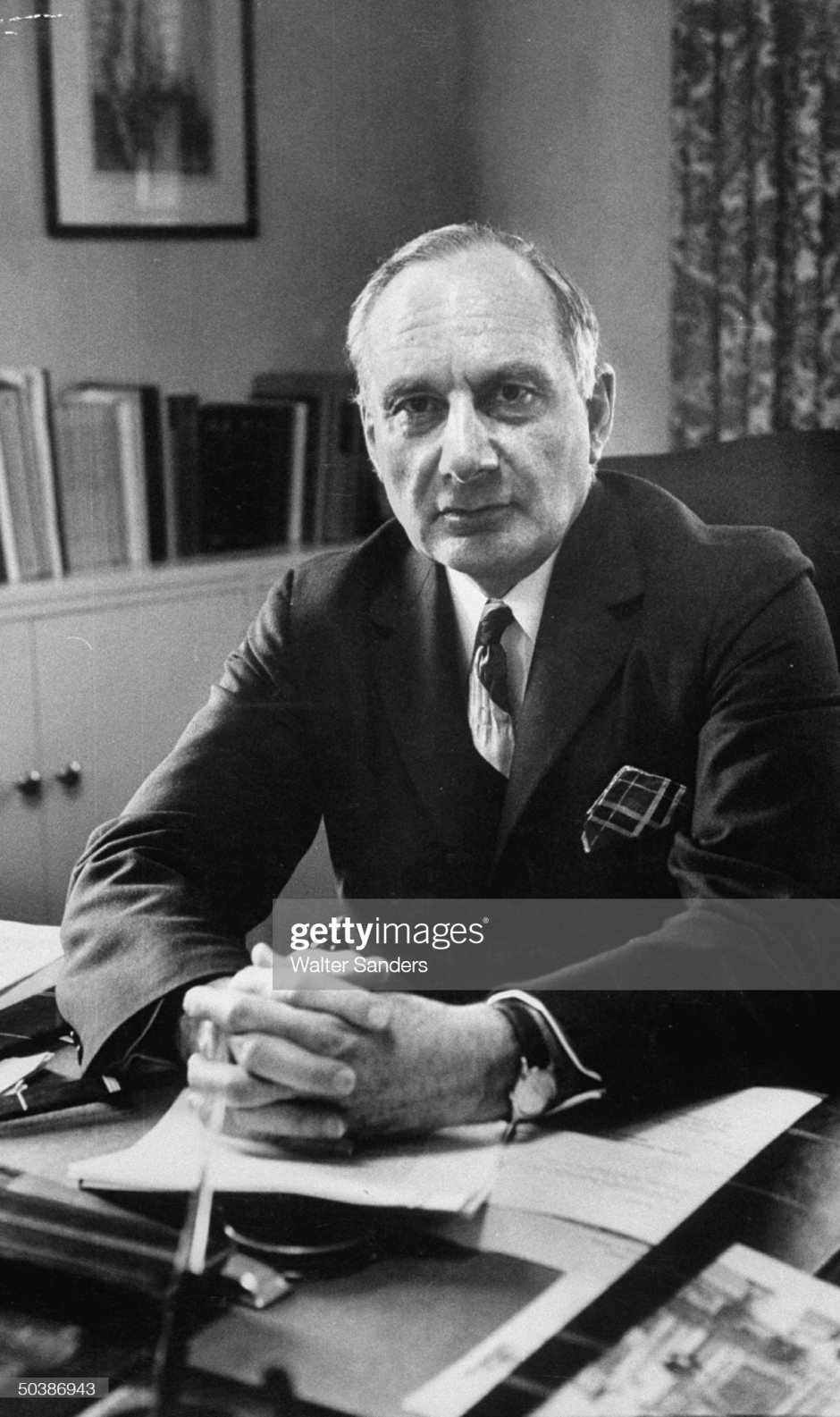

Harry Emerson Fosdick and The Fundamentalist / Modernist Conflict

The 1890s saw great changes in society: The industrial revolution and the changing of the United States from an agrarian society to an urban one.

The 1890s were also a decade of intellectual upheaval. Between the depression of 1873 and the First World War, many of the time-honored suppositions were being questioned. Darwin’s theory of evolution was one of the most prominent new ideas, challenging the authority of the Bible and the presumption of its inerrancy.

A working definition of Modernism, Liberalism and Fundamentalism in the American Protestant context is necessary to understand the basics of the conflict.

Traditionalists, later known as Fundamentalists, adopted a five-point declaration at the 1910 General Assembly that all candidates for ordination had to affirm. These five points were of course a reaction to the growing acceptance within Protestantism and, specifically the Presbyterian Church, of a more liberal interpretation of the Bible.

The five Fundamental points are:

1.The inerrancy of the Bible

2.The virgin birth of Christ

3.Christ’s substitutionary atonement

4.Christ’s bodily resurrection

5.The authenticity of Christ’s miracles

Other Christian groups adapted the five points with point two often becoming the deity of Christ rather than his virgin birth.

Many lists ended with Christ’s premillennial second coming, instead of his miracles, as the fifth point.

By the 1920s the five points had become called the five fundamentals and had become a rallying cry for conservative Christians across a broad spectrum.

As Jack Rogers, in his book Presbyterian Creeds: A Guide to the Book of Confessions, states: “This was especially true for the growing movement of independent Bible conferences, Bible schools, and independent churches influenced by Dispensationalism. This movement majored in literalistic, futuristic, interpretation of biblical prophecy which announced Christ’s imminent return following a very specific and complex timetable of attendant events. Dispensationalists also taught that all the traditional institutional churches had grown worldly and denied fundamental doctrinal beliefs.”

Modernism may be defined as a method of interpreting Christian scripture and tradition, but not a particular set of beliefs. Modernizers can be found in every period of Church history and Christian Communions. But when we speak particularly of Protestantism in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, we see a conviction in the new scientific knowledge and the most recent Biblical historical research. An application of this new knowledge presents real issues for Christians. As a result, according to Modernism, the task of interpretation must be carried forward if the saving truth of the gospel is to be understood in its relevance to contemporary life.

As for Liberalism, Daniel D. Williams, former Professor of Systematic Theology at Union, says, “It might be said with some accuracy that all theological liberals were modernists; but not all those who used modernist methods of interpretation shared the faith of the liberal theology, especially its optimistic estimate of human nature.”

Further, he says: “Liberals have taken a positive attitude toward the achievements of democratic culture and have generally stressed the ethical imperatives in the gospel.”

Williams also quotes the German theologian Adolf Harnack, who, near the turn of the century, had this classic definition of Liberal theology: “Firstly, the Kingdom of God and its coming. Secondly, God the Father and the infinite value of the human soul. Thirdly, the higher righteousness and the commandment of love.”

In the social gospel movement Walter Rauschenbusch, who was professor of Church History at Rochester Theological Seminary in the early part of the century, became a chief interpreter and prophet. His concept of social sins involved society as a whole (e.g., poverty, child labor, poor working conditions, etc.), and held that these needed to be urgently addressed. To Rauschenbusch and his followers, Christian social activism and advocacy was a compelling Biblical ethic.

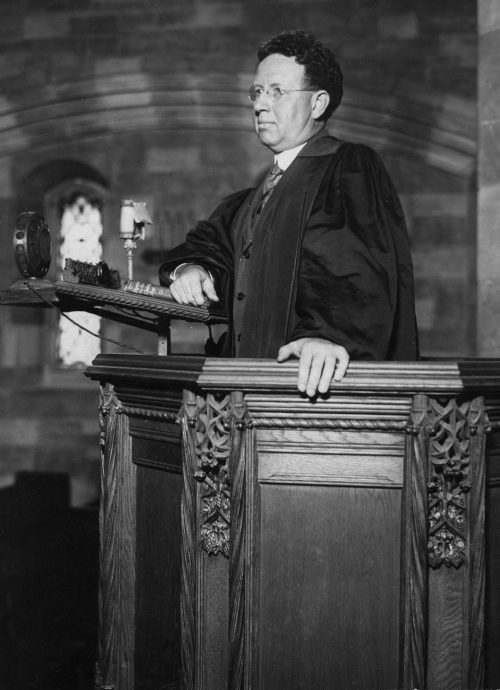

The Fundamentalist / Modernist conflict began with the Charles A. Briggs heresy trial. The trial was a reaction from conservative traditionalists to Briggs’s address on January 20, 1891, at Union Theological Seminary on, “The

Authority of the Holy Scriptures.” It was an address inaugurating the opening of the new Department of Biblical Theology.

Briggs was a professor of theology at Union, and he attacked “Traditionalism,” later known as Fundamentalism, and espoused an interpretation of the Bible in the light of the “Higher Criticism.” The Higher Criticism was a method of investigating facts based on scientific investigation, inductive research, and a relative system of values.

Carl E. Hatch, in his 1969 book The Charles A. Briggs Heresy Trial, lists three main factors that stand out as transforming American Protestant theology: Darwin’s theory of biological evolution, Higher Criticism, and the study of comparative religion. Hatch further makes the point that the impact of Darwin’s theory of evolution on American Theology is well known, but that of Higher Criticism and comparative religion much less so.

Briggs had studied in Germany where the methods of Higher Criticism had begun. Julius Wellhausen had perhaps the most influence upon American theologians. He is known as the Father of Higher Criticism. Briggs’s favorite teacher at the University of Berlin, which he attended, was A.I. Dorner, a disciple of Wellhausen.

Charles A. Briggs was born in New York City on January 15, 1841. He attended the University of Virginia, but in his Junior year, 1861, returned home because the Civil War was imminent. After joining the Union Army for about a year and helping defend Washington D.C., he was released to go home, for reasons not known. He entered Union Seminary and graduated in 1863. After graduation he tried helping his father in his merchandising firm in New York, but quickly decided it was not for him. Briggs then matriculated to the University of Berlin. It was a turning point in his life.

After completing his studies, he returned to New York and in 1870 was ordained a Presbyterian minister. He served for a time at a church in Roselle, NJ, but soon found that it, too, was not to his temperament. In 1874 an invitation came to teach at Union. He was professor of Hebrew and Cognate Languages. Although he found it much more rewarding to teach than be a pastor, the subject did not afford him much opportunity to approach Biblical criticism.

Briggs had wanted to forcefully introduce the German theology into this country, but “How to do it?” was his question.

Since Union was under the control of the General Assembly, and most Presbyterian clergy were conservative and therefore disposed against the German Higher Criticism, Briggs had to be careful in what he wrote in religious publications and what he taught in the classroom.

Briggs then maneuvered to create a new department, using the Higher Criticism. But instead of using that term, he used the euphemistic “Department of Biblical Theology.” Briggs, of course, was to be head of the department.

Little opposition was encountered from Union faculty or administration for the creation of the new department. For, despite generally conservative clergy within the Church, Union’s faculty and administration at the time were more progressive and favorably inclined toward the German theology. Charles Butler, chairman of Union’s board of directors, had been a boyhood friend of Briggs and supported the plan wholeheartedly. In April of 1890 Union received $100,000 in bequest money for the new department. The board voted in the new department unanimously in November of that same year.

On January 20, 1891, Briggs gave his address inaugurating the new department.

The speech cheered Briggs’s students. They enthusiastically applauded him at points, but it angered the invited conservative guests and clergy.

The speech is very much a polemic, attacking beliefs about the Bible that the Victorians held as eternal and inviolable.

Briggs began by asserting that there were three, not one, great sources of divine authority. The first was the institutional Church, the second was reason, and the third the Bible.

“But of all three ways,” Briggs said, “no one of these has been so obstructed as the Holy Bible.” He argued that the authority of the Bible had been so wrapped in dogma and protective creeds, that “The whole trouble with the Bible today is that it has been treated as if it were a baby, to be wrapped in swaddling clothes, nursed, carefully guarded lest it should be injured by heretics and skeptics.”

As Carl Hatch relates in his book, “The net effect of this,” according to Briggs, “was to shut out the light of God, to obstruct the life of God, and to fence in the Bible, thus rendering the Bible useless.”

Briggs next attacked superstition as keeping people from the Bible. “We are accustomed to attach superstition to the Roman Catholic Mariolatry and the use of images, and pictures and other external things in worship. But superstition is not less superstition if it takes the form of Bibliolatry.” Mariolatry is idolatry of the Virgin Mary. Bibliolatry is idolatry of the Bible.

“The second barrier,” said Briggs, “keeping men from the Bible is the dogma of verbal inspiration.” These comments, reports Hatch, were “extraordinarily incendiary because the doctrine of verbal inspiration was (and still is) one of the dearest tenets of evangelical Protestantism.”

In Briggs’s third barrier, he maintained that the idea that the Scripture is inerrant is false. “The Bible itself nowhere makes the claim that it is inerrant,” said Briggs.

The fourth barrier, said Briggs, was the assumption that the authenticity of the Bible was founded upon the belief that holy men of old had written the various books.

Said Briggs: “When such fallacies are thrust in the face of men seeking divine authority in the Bible, is it strange that so many turn away in disgust? It is just here that the Higher Criticism has proved such terror in our times. Traditionalists are crying out that it is destroying the Bible, because it is exposing their fallacies and follies. It may be regarded as the certain result of the science of the Higher Criticism that Moses did not write the Pentateuch or Job; Ezra did not write the Chronicles, Ezra or Nehemiah; Jeremiah did not write the Kings or Lamentations; David did not write the Psalter, but only a few of the Psalms; Solomon did not write the Song of Songs or Ecclesiastes, and only a portion of the Proverbs; Isaiah did not write half of the book that bears his name. The great mass of the Old Testament was written by authors whose names or connection with their writings are lost in oblivion.”

At last Briggs ended his shocking pronouncements with this vigorous exhortation:

“We have undermined the breastworks of Traditionalism; let us blow them to atoms. We have forged our way through the obstructions; let us remove them now from the face of the earth, criticism is at work everywhere with knife and fire! Let us cut down everything that is dead and harmful, every kind of dead orthodoxy, every species of effete ecclesiasticism, all mere formal morality, all those dry and brittle fences that constitute denominationalism, and are barriers to church unity.”

“Let us burn up every form of false doctrine, false religion, and false practice. Let us remove every incumbrance out of the way for a new life; the life of God is moving throughout Christendom, and the spring time of a new age is about to come upon us.”

With this blistering attack upon the traditionalists, Briggs faced considerable reaction from within the Church in the form of open theological warfare. Before this, the Higher Criticism posed only a vague threat to the traditional theology. Briggs, in one speech, had moved it full throttle into a formidable threat to upset the prevailing orthodoxy.

It is interesting to note the overwhelmingly positive reaction the students had to Briggs’s speech and theological position. His students were about the same age as Harry Emerson Fosdick was at that time, and as you may remember, Fosdick reports that as a student at Colgate he himself rebelled against the old orthodoxy.

The initial public reaction to Briggs and his theological outlook was cool, but in many newspaper editorials there was a sense of outrage and dismay.

In April of 1892 the Presbytery of Cincinnati petitioned the General Assembly to take action against Briggs. By the time of the General Assembly in May, over seventy presbyteries, mostly from the Midwest, registered disapproval with the Assembly over Briggs’s teachings.

Most wanted the Assembly to order Union to remove Briggs, a power the Assembly had by the Compact of 1870 which had adjoined Union to other Presbyterian seminaries. The Compact clearly stated that the Assembly had power over the accepting or rejecting of professors.

The Union Faculty was solidly behind Briggs. Most favored the German Higher Criticism and rallied behind Briggs. Union alumni were also invited to join in the defense of Briggs. A solid majority of them did. One thing this showed was how much the higher criticism had penetrated into certain circles of American religious thought, despite an era generally marked by conservatism.

At the May General Assembly in Detroit, the Committee on Theological Seminaries, made up entirely of conservatives opposed to Briggs, voted to recommend removing Briggs as chair of the new Department of Biblical Theology.

The Cincinnati Presbytery even tried to organize a boycott by forbidding students of the Midwest to enter Union. The ploy eventually failed because it helped Union gain even greater notoriety for its theological position, thereby attracting more students, especially from New England. Union was now seen at the level of Yale and Harvard Divinity Schools.

At the same time, the Midwestern Presbyteries in 1891 put pressure on the New York Presbytery to bring a heresy charge against Briggs. In May that year a committee of inquiry, involving both liberals and conservatives in the Presbytery, recommended prosecution of Briggs.

By November of 1891 a trial had started. Briggs acted as his own counsel, making a brilliant opening statement that shifted the focus of the trial away from him personally to focus on the new theology. The trial was seen publicly as a forum on this theology, not on the heresy of Briggs’s teaching. Briggs was acquitted of heresy by a 94-39 vote.

Briggs was retried on appeal of the Portland, Oregon Presbytery, and again acquitted. However, at the General Assembly of 1893 he was suspended from the Presbyterian Church.

Meanwhile, Union separated from the Presbyterian Church over this case and retained Briggs as professor until his death in 1913.

Carl Hatch writes, “Although Briggs’ inaugural address did not actually begin a new era in American theology, biblical study in this country has never been the same since that provocative discourse.”

Fundamentalists and Liberals lived in tension in the following years. Presbyteries mostly in the Midwest and West were conservative. Those in the East were more progressive.

One area of tension was in the field of foreign missions. It was in 1921 that Fosdick went to China to ease tensions between missionaries representing churches from both sides of the fence. It was apparently the Fundamentalists that primarily wanted to be separate from their more liberal counterparts.

Reinhold Niebuhr, as a Midwesterner, saw the old traditionalist religion as a kind of rough and ready theology for the American frontier of the 19th century that had hardened into a graceless one for the 20th century.

In May 21, 1922 Fosdick preached “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” He writes in his autobiography, “It was a plea for tolerance, for a church inclusive enough to take in both liberals and conservatives without either trying to drive the other out.” Soon after the sermon, a man named Ivy Lee, a publicist and Presbyterian, asked Fosdick for permission to reprint the sermon in pamphlet form. Fosdick gave him permission and Lee mailed copies to every Presbyterian clergy in the country. A tremendous controversy ensued, with Fundamentalists within the Presbyterian Church, led by William Jennings Bryan, calling for Fosdick’s removal at the General Assembly of 1923.

In the meantime, Clarence E. Macartney, a minister from Philadelphia, preached a response to Fosdick, titled “Shall Unbelief Win?”

That General Assembly produced a resolution directing the New York Presbytery to direct First Church to conform to the Confession of Faith in its preaching and teaching. Fosdick handed in his resignation, but it was rejected by the Session. At the 1924 General Assembly, with Macartney as moderator and Bryan as vice moderator, Fosdick’s preaching remained an issue, and a compromise was finally struck between the two factions, asking Fosdick to regularize his position at First Church by becoming a Presbyterian minister. He refused, and in October of that year the Session accepted his resignation.

Also in that year, 13 percent of the ministers of the Presbyterian Church signed a document called the Auburn Affirmation. It stated that the Five Fundamentals, which the General Assembly had reaffirmed the previous year, went beyond the facts which the Scripture and the Westminster Confession obligated them.

Fosdick’s last sermon at First Church was on March 1, 1925. It was the same year as the Scopes trial in Dayton, Tennessee, in which William Jennnings Bryan came to national prominence.

In 1923, J. Gresham Machen’s book Christianity and Liberalism was published, adding fuel to the fire. It proclaimed that liberal Christianity was “a different religion” and he attempted to argue that it sprang from different roots. Consequently, he advocated a split within the Presbyterian Church along theological lines of ideology.

Machen was a professor at Princeton Theological Seminary. His aggressively militant view contrasted as polar opposite to the one to which Fosdick expressed.

As Jack Rogers says in Presbyterian Creeds, by 1925 “there were identifiable political parties within the Presbyterian Church. One was composed of theological liberals, who believed in an inclusive church, containing any who wished to belong. Opposed to them were doctrinal fundamentalists, who argued for an exclusivist church composed only of those who agreed with the five fundamental points. The largest group, though least well organized, was made up of moderates, who were theologically conservative but were inclusivists for the sake of the peace, unity, and mission of the church.”

Charles R. Erdman, a professor of practical theology at Princeton was elected Moderator of the General Assembly of 1925. Erdman was a moderate. He proposed a Special Theological Commission to study the state of the Church.

In 1927 the commission issued its final report, saying that no one, not even the General Assembly, had the right to single out doctrines such as the five points and determine a particular interpretation of them to be “essential and necessary” for all. They affirmed that only the Judicial process of the church – i.e., heresy trials – could determine points of doctrinal interpretation in specific cases.

Fundamentalist control of the Presbyterian Church was being diminished by altering the theological decision-making by the Presbyteries.

In 1929 the General Assembly approved a reorganization of the governing boards of Princeton Theological Seminary. As a result, exclusivist Fundamentalists were no longer in control.

J. Greshem Machen was outraged. With three other faculty members, he left to form Westminster Seminary in Philadelphia, and soon thereafter, an Independent Board of Foreign Missions. It was a counter to what he felt was a too-liberal influence in the denomination’s foreign missions program.

The General Assembly declared this competition with a denominational agency unconstitutional, and ordered all Presbyterians, including Machen, to desist from this activity. Machen refused and in 1935 he left the Presbyterian Church and formed, with some of his most militant followers, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church.

By the late 1930s, the public had become tired of the tensions between the left and right within the church. Liberal theology had prevailed, but a new wind was blowing. This time, again from Europe.

As Rogers states: “It was not a well-defined school of thought but a new movement variously called ‘dialectical theology,’ ‘neo-Calvinism,’ and ‘neo-Orthodoxy.’ Among its most prominent figures were the Swiss theologians Barth and Brunner and the American Reinhold Niebuhr.”

“Neo-Orthodoxy rejected,” says Rogers, “the evolutionary idealism of liberalism, which had taught that human beings were basically good and that, by cooperating with God, people would bring the kingdom of God on earth. In contrast, Barth and others preached about human sin and a God of judgment and grace who would have to break into human history.”

Neo-orthodoxy, which essentially came out of Liberalism, did not, however, reject the Higher Criticism concerning the Bible. According to Rogers: “The defining insight of early neo-orthodoxy was that God did not reveal information in an inspired book. God was revealed in the person of Jesus Christ. A person’s encounter with Christ in Scriptures was the work of the Holy Spirit.” By the late 1950s neo-orthodoxy was well established as the dominant theology within the Presbyterian Church.

Returning to Fosdick, in 1935 he preached a sermon at The Riverside Church called “The Church Must Go Beyond Modernism.”

In it he declared, “Fifty years ago the intellectual portion of western civilization had turned one of the most significant mental corners in church history and was looking out on a new view of the world. The church, however, was utterly unfitted for the appreciation of that view. Protestant Christianity had been officially formulated in pre-scientific days. Modernism, therefore, came as a desperately needed way of thinking. It insisted that the deep and vital experiences of the Christian soul, with itself, with its fellow, with its God, could be carried over into this new world and understood in the light of the new knowledge. We refused to live bifurcated lives, our intellect in the late 19th century and our religion in the early sixteenth century. God, we said, is a living God who has never uttered his final word on any subject.”

“The church thus had to go as far as modernism but now the church must go beyond it. Modernism is primarily an adaptation, an adjustment, an accommodation of Christian faith to contemporary scientific thinking. It started by taking the intellectual culture of a particular period as its criterion and then adjusted Christian teaching to that standard. Herein lies modernism’s shallowness and transiency: it arose out of a temporary intellectual crisis; it became an adaptation to, a harmonization with, the intellectual culture of, a particular generation. That, however, is no adequate religion to represent the Eternal and claim the allegiance of the soul. Let it be a modernist who says that to you!”

Fosdick goes on to say that modernism had been too preoccupied with intellectualism, too sentimental with the belief in the idea of human progress, that it had been too centered on the achievements of humanity, putting God in a kind of “advisory” position. And finally, that modernism had lost a moral standing-ground by being too accommodating to the prevailing culture.

“Harmonizing slips easily into compromising,” said Fosdick. “To adjust Christian faith to the new astronomy, the new geology, the new biology, is absolutely indispensable. But suppose that this modernizing process, well started, goes on and Christianity adapts itself to contemporary nationalism, contemporary imperialism, contemporary capitalism, contemporary racialism – harmonizing itself, that is, with the prevailing social status quo and the common moral judgments of our time.”

“We cannot harmonize Christ with modern culture,” said Fosdick at the end. “What Christ does to modern culture is to challenge it.”

In this sermon Fosdick never renounces Liberalism – many thought he had – or even mentions it by name. Fosdick still strongly believed in humanity and its possibilities in relation to God and still believed in the progress of Christianity as revealed by God. His 1938 book A Guide to Understanding the Bible demonstrates this. But his thinking and beliefs by this time had developed more like those of the emerging neo-orthodox theology.