February 24, 2022

Outside Tulum SFER IK Shakes up the Familiar Museum Model

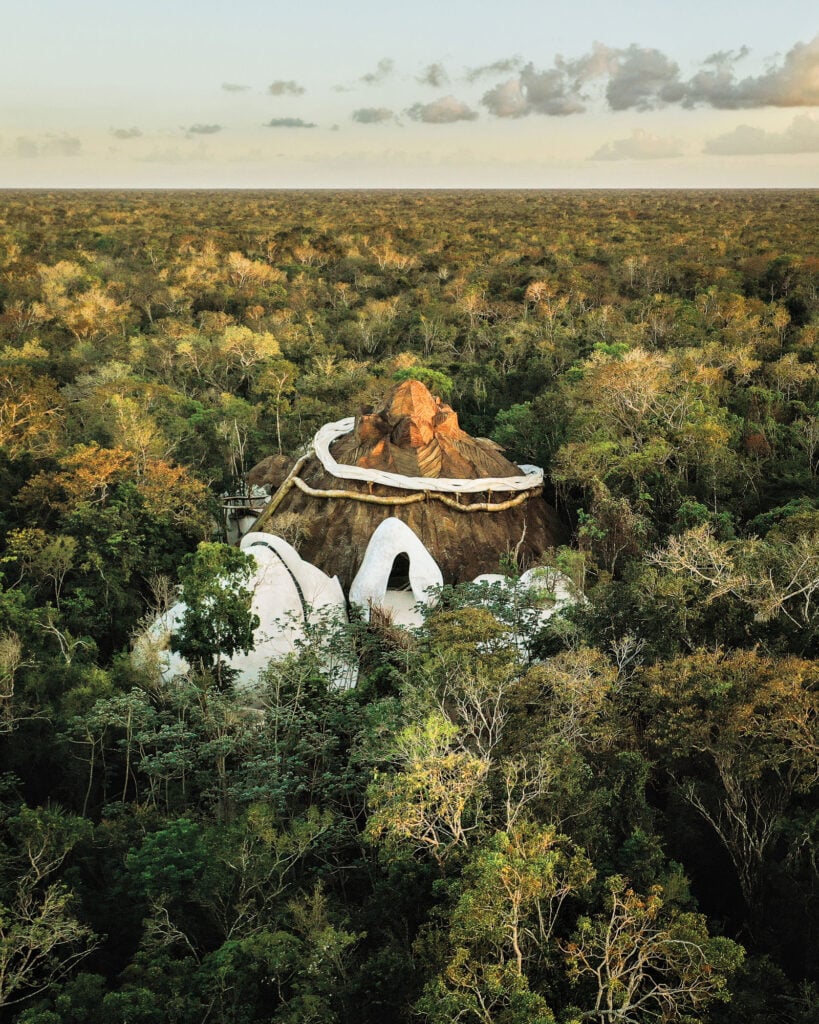

SFER IK, which gets its name from its curvilinear design (it’s pronounced the same as “spheric,” and there are no straight lines anywhere in the structure), is ensconced in a ten-acre creative community within Francisco Uh May, a tiny jungle town about a half hour’s drive from the fashionable resorts of Tulum. Containing around 13,000 square feet of exhibition space, the institution invites artists to participate in residencies, living for a time in the complex and absorbing its natural and cultural inspiration before creating work that grows organically out of the place and its people.

And you can see how. The building is in almost every way an extension of the jungle that surrounds it. An armature of smooth, thin concrete wraps like a ribbon, or a giant swirling candy, around the site, forming floors, walls, tables, and walkways. Several existing trees stand where they have always been; vinelike, intricately textured local bejuco wood, fiberglass, and the limbs of other local trees form more floors, walls, pathways, railings, and window frames; vines hang from the ceiling. The overall form looks like a mountain from above. It’s not hermetically sealed like a typical art gallery. If it rains, some water gets into the flowerpots and trees, says Roth.

The building’s eye-popping forms were created with the help of temporary steel scaffolding, which enabled a top-down building technique that the team adapted from local wood frame palapa construction. Another key was to follow the lead of nature, rather than chasing a preconceived notion of what the building needed to be. The only hard rule was to build around what existed on the site. Another directive was to use the rounded, irregular forms of nature and to build as much as possible by hand, not machine.

“Everything we build, we never have a plan,” says Roth. “We let a shape be born in our imagination and without any restrictions of conventional architecture, we find the way to make them real. You see the implicit forms of plants…. We are like midwives giving birth to the forms that want to be part of the whole.” He adds: “In the jungle, people have the intelligence of the hands. Hands are intelligent and sensitive.”

Around the museum Roth’s team has built a community of living spaces as well as studios for macramé, ceramics, textiles and fashion, woodworking, and even media production and architecture. There are constant workshops where new skills are taught and learned, and the community’s craftspeople provide most of the facility’s own designs, from plates to tables.

Artists are experimenting inside the space already, but the first to install a monographic exhibition in the museum since its pandemic-induced hiatus (the opening is expected in early 2022) will be the Japanese floral designer and sculptor Makoto Azuma, whose work appropriately explores the intersection between the fantastical and the botanical. The museum’s director, Marcello Dantas, has worked with established museums and galleries around the world. He’s especially inspired by collaborating with artists in a place that doesn’t just look and feel different but inspires artists to work in a new way. “It’s about surprise and connection,” he says.

He considers SFER IK’s audience to be more than locals and visitors, but bats, birds, scorpions, fungi, and trees. “You realize you have never been in a place like this,” says Dantas. “If we don’t find a way to make artworks that are relevant to the species that surround us, we are irrelevant. We’re a small piece in this giant jungle.”

Completely eschewing the form of the box, adds Roth, is a model not just for the art world but for humanity at large. “When you work in a box, your mind becomes like a box,” he notes. “When you go into the jungle, everything is new and renewed. You harmonize with nature and go back to your origin. You reconnect with what you are. With life.”

Related

Viewpoints

Google’s Ivy Ross Makes Sense of Color

METROPOLIS sits down with Ivy Ross, Google’s vice president of hardware design, to discuss Making Sense of Color, now on view during Salone del Mobile 2024.

Viewpoints

Two Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2024

The building industry makes vital moves toward standardization and transparency on energy efficiency and social impact.

Viewpoints

How the Design Industry Is Navigating the Sustainability Surge

Discover new ThinkLab research that suggests sustainable design is hitting its stride.