Welcome to Site Saturday! This week we are going to talk about one of the most fascinating sites in all of Egypt. This site is Deir el-Medina, which is one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of community life in the ancient world. The citizens of these villages were skilled artisans who built and decorated the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings and Queens during the New Kingdom.

Location and Name

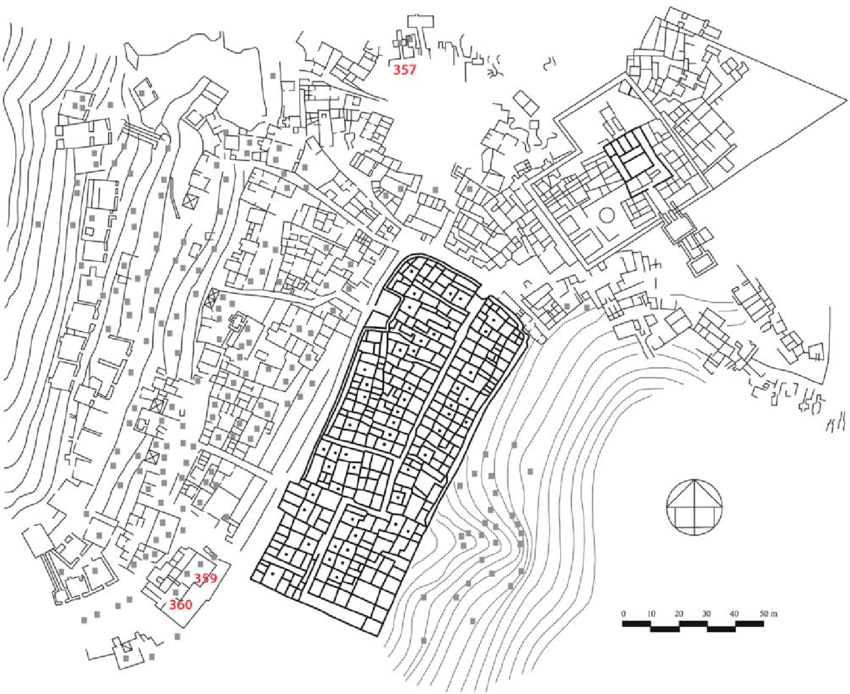

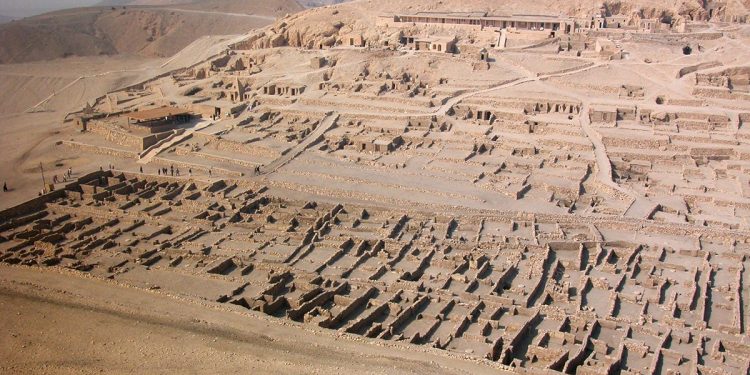

Deir el-Medina is in a quite unique location as it is on the west bank of the Nile across from Thebes/Luxor (just north west of Amenhotep III’s palace Malqata). It is laid out in a natural amphitheater within walking distance from the Valley of the Kings to the north, the Valley of the Queens to the west, and the funerary temples to the east and south east.

The ancient name of the village was Set Maat, meaning “Place of Truth,” though that is only what the Egyptian officials called it. The locals called it Pa Demi, which simply meant “The Village.” The official name was thought to be inspired by the gods in creating the eternal homes of the deceased kings and their families. Those that lived in the village were called “The servants of the Place of Truth.” During the Christian era, the temple to Hathor in the village was converted to a church called Deir el-Medina in Egyptian Arabic, which means “the Monastery of the town.”

Layout of the Village

This was not a village that grew up organically. This was a planned community, most likely founded by pharaoh Amenhotep I in the 18th Dynasty. It was most likely built apart from the wider community in order to preserve the secrecy of the work being carried out in the tombs. Pharaohs during the New Kingdom moved from building massive funerary tombs, like the pyramids of Giza, to rock cut tombs built up in the cliffsides. By doing this, they hoped that their tombs would not be robbed, and the pharaohs would be able to enter the afterlife comfortably with all their possessions. Deir el-Medina was built to contain all the workers and artisans who worked on the tombs and would thus know crucial details. That is not to say that the people of Deir el-Medina didn’t rob the tombs, but we’ll talk about that later.

Although Amenhotep I probably planned the village, there are some remains that date to his father, Thutmose I’s reign. The village reached its peak during the Ramesside Period and was most likely abandoned by the end of the New Kingdom.

Although Amenhotep I probably planned the village, there are some remains that date to his father, Thutmose I’s reign. The village reached its peak during the Ramesside Period and was most likely abandoned by the end of the New Kingdom.

The site is about 1.4 acres with a surrounding wall. The main entrance to the town was in the north wall and there may have even been a guard house next to the gate. The community could move freely in and out of the village, but outsiders were only allowed to enter the site if they were there for work related reasons. At it’s peak, the village had around 68 houses with a main road running the length of the village. This road may have actually been covered to shelter the villagers from the glare and heat of the sun.

What is most interesting about the village is that they were not self-sufficient. Because they were located in the hills above the Nile, they didn’t have a central well for a water supply. They were within a 30 min walk to the nearest well, so someone had to continuously help supply the village with water. The surrounding area would not have been able to sustain agriculture. Let alone, the villagers were not farmers, but artists!

The houses were designed as long rectangles, running from the street to the surrounding wall. They had an average floor space of 70 square meters or 753 square feet. Because the village was planned, all the buildings were made with the same materials and construction methods. The walls were made of mudbrick on top of a stone foundations. Mud was applied to the walls, which were then painted white on the outside. Some of the internal walls were also painted white on the bottoms.

The houses contained four to five rooms each, usually comprising of an entrance, main room, two smaller rooms, a kitchen with a cellar, and a staircase leading to the roof. Some of the houses may have had a wooden door with the name of the occupants. You would step up into the living room, then proceed to the other two rooms, before reaching the kitchen in the back of the house. It had an open roof, possibly with a thatched roof to both allow smoke to leave and block the sun. The windows of these houses were also very high up on the walls to block the glare of the sun. Nearly all the houses had niches for statues or altars and a mud brick platform which may have been used as a shrine or a birthing bed. None of the rooms were designated solely as bedrooms.

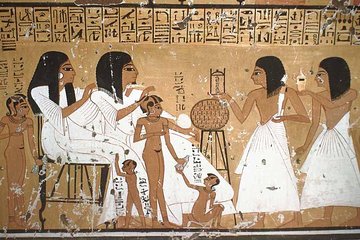

Surrounding the village are their tombs. These mostly consist of rock cut chambers and chapels, sometimes with small pyramids. Because these villagers were artisans, these tombs are beautifully decorated. Check out these links to look inside some of the tombs!

Community

The village was home to a mixed population of Egyptians, Nubians, and Asiastics who were employed as laborers (ie. stone cutters, plasters, water carriers), administrators, or decorators. The artisans were organized into two groups who also lived in different parts of the village. These were called left and right gangs and then worked on the respective sides of the tombs at the same time, with a foreman for each side. When working in the village, the artisans stayed overnight in a camp that overlooked the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut, which is at the base of the cliffs that contain the Valley of the Kings. The workers had cooked meals delivered to them for the village.

The workmen were considered middle class, based on the record of their income and prices. They were salaried state employees, which meant that they were paid in rations. They also were known to practice unofficial second jobs as well. A working week was eight days followed by a two-day holiday. The six days off a month could be supplemented frequently due to illness or family reasons. There are even some records of taking the day off work because they were arguing with their wife or had a hangover! Workmen were also given days off for festivals as well as being issued extra supplies of food and drink to allow a larger celebration. During these days off, the workmen were allowed to work on their own tombs or take extra jobs.

The Egyptians did not use coinage for money until the Roman period, so jobs were paid with rations or through bartering. There was a continuous trade between houses of items like sandals, beds, baskets, paintings, amulets, loincloths, and toys for the children. A worker might build an addition to the house or roof in exchange for anything from a sack of grain, jug of beer, or a painting of a god or goddess in a personal shrine.

We don’t have any evidence of female artisans from this village, so it can be assumed that the village was mostly occupied by women and children while the men were away. Deir el-Medina itself provides the most information about non-royal women from the New Kingdom. Because they stayed in the village while the men were away, the government supplied them with servants to assist with the grinding of grain and laundry tasks. The wives of the worker would care for the children in the village and baked bread for the community. The vast majority of the women in the village could hold titles of chantress or singers, which meant that they held official positions within the local shrine or even the larger temples in Thebes. Women who were titled as mistress of the House could also work supervising the brewing of beer. Although some workmen used this activity as a legitimate excuse for taking time off of work.

Women even had property rights under Egyptian law. They had a title to their own wealth and a third of all marital goods. These would belong solely to the wife in case of divorce or the death of the husband. If the wife was to die first, it would go to her heirs, not her spouse. One will of a woman named Naunakhte was found in Deir el-Medina in 1928. It dates to the 20th dynasty, during the reign of Rameses V and is currently located at the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford (1945.97).

The Lady Naunakhte, who was labeled as a citizen and not a servant or slave, was married twice, first to a scribe Kenhikhopshef, with whom she had no children, and then to the workmen Khaemnun, with whom she had eight children. In her will, she lays out the inheritance to only her five oldest children, Maaynakhtef (male), Kenhikhopshef (male), Amennakht (male), Wosnakhte (female), Manenakhte (female). They were labeled as good children who took care of their mother in her old age. Her son Kenhikhopshef even received a bronze washing bowl. Although her last three children, did not receive anything in her will, she does remind them that they could receive items from their father. How I would love to see the will of Khaemnun to compare!

Religious Beliefs

In Deir el-Medina, the state gods were worshiped alongside personal gods without any conflict. The community had 16 to 18 chapels, the largest of which were dedicated to Hathor, Ptah, and Ramses II. The workmen typically honored Ptah, Resheph, originally a Canaanite god associated with plague, war, and thunder, Thoth, and Seshat. Women were devoted to Hathor, Taweret and Bes in pregnancy, and Renenutet and Meretseger for food a safety.

There was also a funerary cult dedicated to pharaoh Amenhotep I and his wife Ahmose-Nefertari. Amenhotep became Amenhotep of the Town and his wife because Mistress of the Sky and Lady of the West. The villagers held a festival every year dedicated to the pharaoh and his wife. The god Amun was also seen as a patron of the poor and one who was merciful to the penitent.

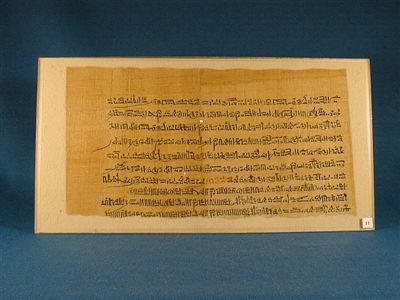

Dream interpretation also fell under the religious culture of the village. A book of dreams was found in the library cache of the scribe Kenhirkhopesehef. This book was used to interpret various types of dreams. Apparently the interpretation of the dream was often the opposite of what the dream depicted. Meaning, a happy dream could mean sadness or vice verse. Here are some examples:

- If a man sees himself dead this is good; it means a long life in front of him.

- If a man sees himself eating crocodile flesh this is good; it means acting as an official amongst his people. (i.e. becoming a tax collector)

- If a man sees himself with his face in a mirror this is bad; it means a new life.

- If a man sees himself uncovering his own backside this is bad; it means he will be an orphan later.

Historical Records

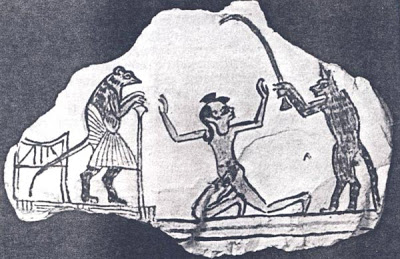

A large proportion of the community, including women, could at least and possibly write. Deir el-Medina itself contributed significantly to the literacy percentages in New Kingdom Egypt. This is seen especially in the vast number of ostraca and papyri remains that were found in Deir el-Medina. Ostraca are small pieces of stone or broke pottery, which were then written or drawn on. These could be funny scenes, literary texts, or important documents.

The surviving texts record the events of daily life rather than the major historical incidents, which is what the majority of other contemporary texts describe. Personal letters, records of sales transactions, prayer, law and court cases, medicine, love poetry, and literature are just some of the examples of the texts founds. Thousands of papyri and ostraca have still not been published, and it is estimated that half of the surviving records may have been lost to looters when the site was excavated.

As the majority of the workers were free citizens (there were some slaves who lived in the village), they were allowed all access to the justice system. Any Egyptian could petition the vizier and could demand a trial by his peers. The community’s court was made up of a foreman, deputies, craftsman, and a court scribe. They were authorized to deal with civil and some criminal cases, typically relating to the non-payment of goods or services. The villagers would represent themselves and some cases could go on for several years, including one dispute involving the chief of police that last eleven years.

The people of Deir el-Medina also consulted oracles about a variety of topics. Questions could be posed orally or in writing before the image of the god when carried by the priests. A positive response would be a downward dip and a negative response would the priests taking away the idol. They also believed that the oracle could bring disease or blindness to people as punishment or miracle cures as rewards.

A large portion of the ostraca found in Deir el-Medina describe the medical techniques of this time period. As in other Egyptian communities, the workmen and inhabitants of the village received care for their health problems through medical treatment, prayer, and magic. There was both a physician who saw patients and prescribed treatments and a scorpion charmer who specialized in magical cures. The surviving ostraca contain prescriptions, letters, and even semi-official documents such as lists noting the days and reasons for a worker’s absence. One example is a letter from a father to his son, asking for help in treating his blindness (Berlin P 11247). Apparently, it can be cured with honey, dried ochre, and black eye paint, though the instructions were not included.

Tomb Robbing

Tomb robbing was nothing new in ancient Egypt. The majority of tombs and funerary monuments were looted in antiquity, often just a few years after they were sealed. And then anything else was taken in the 18th and 19th century by tourists. If you didn’t know, the reason King Tutankhamun’s tomb was so famous and has created so much allure, is that it was the only intact tomb of a pharaoh.

The villagers of Deir el-Medina were blessed with the knowledge of the location, decoration, and possibly even witnessed the funerary assemblages being placed in the tombs of the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens. Because of this, it has been proposed that the Deir el-Medina villagers were actually the ones who looted many of these tombs and that it became part of the villages culture. During times where there was no work, they may have become desperate and used fences, or people who knowingly bought stolen goods, to loot and sell the finds of the tombs. They may have bribes officials and then would tunnel into the tombs through the back to not be suspected. Viziers would apparently inspect the tomb entrances often to make sure they were sealed. If any items were recovered from the tomb robbers, authorities would not put them back in the tombs, but add them to the treasury.

There are some records of thieves being caught and tortured to interrogate them. The police in the area were called the Medjay, who were responsible for preserving law and order. One of the famous cases was against a man named Paneb who was accused of looting royal tombs, adultery, and causing unrest in the community. There was an entire court case against him, which we unfortunately have no record of the outcome. Although there are other records of a head of the workmen being executed around this time. The adultery of Paneb was well recorded in this ostraca inscription:

“Paneb slept with the lady Tuy when she was the wife of the workman Kenna. He slept with the lady Hel when she was with Pendua. He slept with the lady Hel when she was with Hesysunebef – and when he had slept with Hel he slept with Webkhet, her daughter. Moreover, Aapekhty, his son, also slept with Webkhet!”

The Leopold II and Amherst VII Papyrus detail one tomb robbery. One worker named Amenpanufer confessed to breaking into the tomb of Pharaoh Sobekemsaf II. He and his accomplices opened the sarcophagi and stole amulets, jewelry, and gold. They fled and spilt the loot between themselves. He alone was arrested but gave his share to the official who let him go. And then he returned to his friends, who reimbursed him for losing his share!

Another record, called the Abbot Papyrus, reports that officials were looking for a scapegoat, so they obtained a confession from a repeat offender after torturing him. The vizier was suspicious at how easily the suspect was produced, so he asked the man to lead them to the tomb that he robbed. He led them to an unfinished tomb and lied about who the tomb was made for. Supposedly, he was let go.

Strikes and the Decline of the Village

Throughout the later history of the village, there is evidence of several strikes against the pharaoh. Usually paying proper wages was a religious duty that formed an intrinsic part of Maat, which was a concept of truth or justice that the Egyptians followed. Around the 25th year of Ramses III’s reign, the tomb laborers were experienced severe delaying in supplies. They decided to stop working and wrote a letter to the vizier complaining about their lack of wheat rations. Some of the village leaders attempted to reason with them, but the workers continued to refuse to work as their were force to buy their own wheat. Apparently, the vizier and authorities were able to address their complaints and the workers resumed work. This may have been the first sit-down strike action in recorded history!

There were several strikes after this. The work chiefs continued to support the authorities rather than the workers. Since the workers didn’t trust their chiefs anymore, they chose their own representatives from within the village. After the reign of Ramses IV, the conditions in the village become increasingly unsettled. It is unclear when and why the site was finally abandoned, but it could be presumed that when the pharaoh’s stopped building tombs in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, that the village was emptied.

Excavation History

The earliest find in the area was made in the 1840s. This was a cache of papyri, which hinted at some of the later finds in the village. It was first seriously excavated from 1905 to 1909 by Ernesto Schiaperelli, who was an Italian Egyptologists who had discovered the tomb of Nefertari in the Valley of the Kings. His excavations uncovered a large number of ostraca.

Next, Bernard Bruyère, a French Egyptologist, started excavations around 1922. These of course were overshadowed by Howard Carter’s discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun. He excavated the entire site, including the village, the dump and the cemetery until 1951. During these excavations, a cache of 5,000 ostraca of assorted works of commerce and literature was found in a well near the village.

Jaroslav Černý, a Czech Egyptologist under Bruyère, continued to study the site for almost 50 years. He was able to name and describe the lives of many of the inhabitants of Deir el-Medina. The mountain peak that overlooks the village was renamed Mount Cernabru, in recognition of Černý and Bruyère’s work on the village.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Will_of_Naunakhte

https://www.ancient.eu/Deir_el-Medina/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_Ostraca_of_Deir_el-Medina

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deir_el-Medina

https://deirelmedinaktpl.weebly.com/the-village.html

http://www.ancient-egypt.co.uk/deir%20el%20medina/index.htm

Photo Credits

Wikimedia Commons (Roland Unger) – Ruins image

https://deirelmedinaktpl.weebly.com/the-village.html – Plan of local area

Anne Austin (https://brewminate.com/labor-and-health-care-in-ancient-egypt/) – Picture of Ruins

British Museum (EA 10683,2) – Chester Beatty Papyrus (Dream Book)

Wikimedia Commons (Jeff Dahl) – Edwin Smith Papyrus (Medical Papyrus)

http://near-east-images.blogspot.com/2007/10/and-more-deri-el-medina-ostraca.html – Funny Animal Ostraca

Peter Pavúk (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340666160_A_Mycenaean_Stirrup_Jar_Fragment_from_TT_357_In_The_Deir_el-Medina_and_Jaroslav_Cerny_Collections_II_Pottery) – Plan of Village and necropolis

https://trebolanimation.blogspot.com/2013/12/atlas-de-la-ciencia-y-otros-editorial.html – Reconstruction of the village

https://see.news/dr-zahi-hawass-deir-el-medina-taiba-pharaonic/ – Image of Pyramid shrine and ruins

Wikimedia (Steve F-E-Cameron) – Ruins

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin – Osiride Statue of Amenhotep I

Anagh – Ruins

Archaeological Photography Exchange (Seshta) – Will of Naunakhte

Babara Weibel – Tomb of Sennedjem

Flickr (kairoinfo4u) – Tomb of Sennedjem

http://www.ancient-egypt.co.uk/deir%20el%20medina/index.htm – Outline of House Structure

https://deirelmedinaktpl.weebly.com/role-of-women.html – Tomb of Anherkhawy

Global Egyptian Museum – Papyrus Leopold II

http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/tutrobbery.htm – King Tut robbery map

Wikimedia Commons (French Archaeological Institute in Cairo IFAO) – Excavation of Deir el-Medina

https://bernardbruyre.wordpress.com/?fbclid=IwAR2q5-bvsPwNzKsh4SlbKyIcrq8tMUF3wes_r4SQhbxqrQOE99WKOxbQo9A – Jaroslav Černý images

http://imagenesdeegipto.blogspot.com/2013/09/bernard-bruyere-pinceladas-de-su-vida.html – Bernard Bruyère image