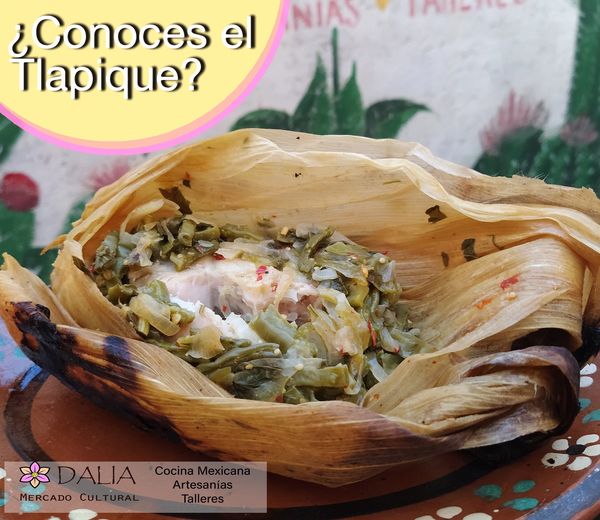

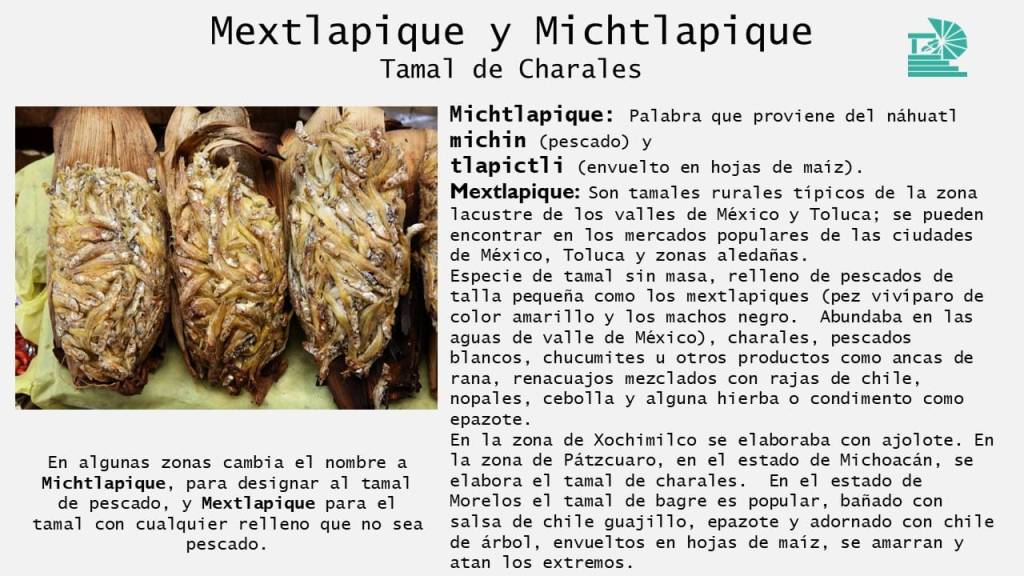

Cover image via the Dalia Mercado Cultural in Xochimilco. (more on these guys at the bottom of the Post)

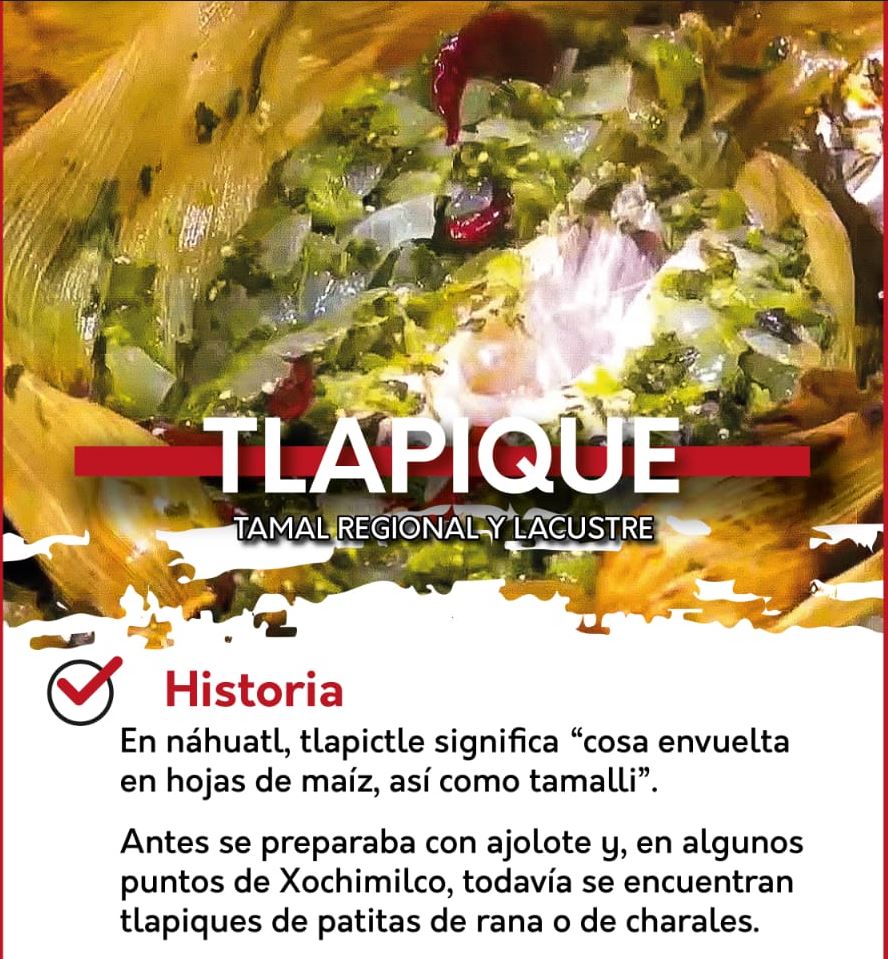

The Tlapique. Cousin of the Tamal.

I have mentioned the tlapique (or mextlapique) briefly in previous Posts (1) but it has come up a few times for me recently and this dish offers insight into Prehispanic culinary arts that warrants further attention. This dish, which at its most basic, is a masa-less tamal, and the investigation of it will introduce you to both a dish and a method of cooking that pre-dates anything Español. If you are looking to decolonise your diet then this dish shows one way to do that (2).

- Yepaquilitl : Another Skunk Weed & Xochimilco and the Axolotl. In this last Post I give a recipe for tlapiques containing the ajolote and a vegan (if such things concern you) recipe which I will repeat at the end of this Post

- As does the tlaltequeada (tlaltequiada). See my Post Prehispanic Veganismo – The Tlaltequeada

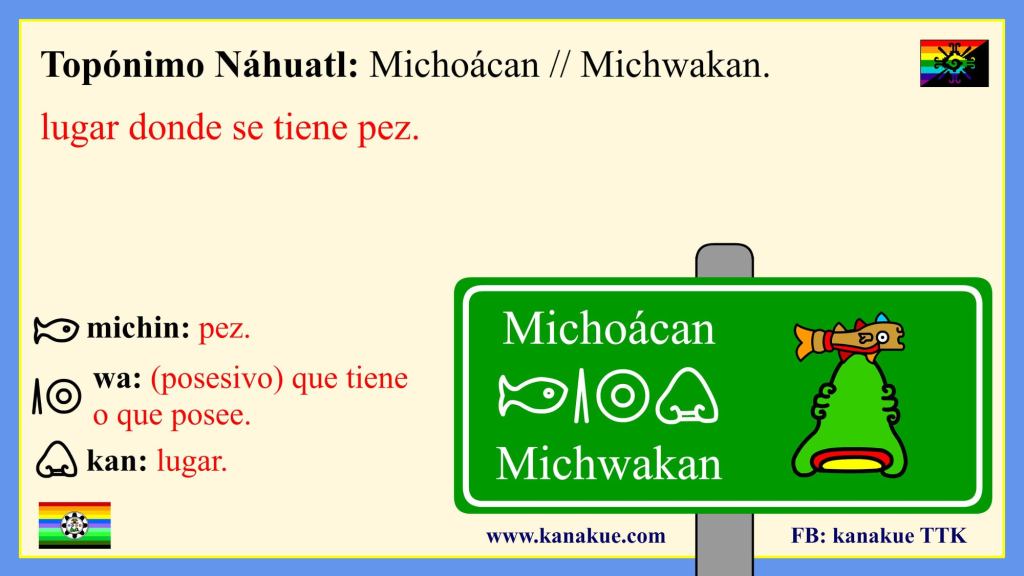

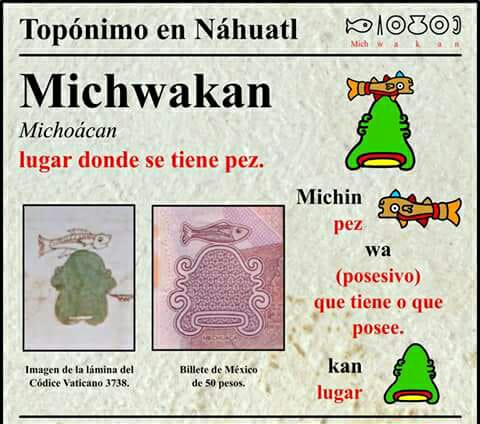

The word tlapique is a contraction of the Nahuatl mextlapique which is derived from “michin” and “tlapictli” (also written as “tlapictle”). Actually “contraction” is probably a misnomer as “tlapictli” seems to be the root word which is changed by the addition of the ingredient (a small fish) to be expanded into the word mextlapique.

- Michin – Principal English Translation: fish (see Lockhart) (1)

- Tlapictli – Principal English Translation : something made up, invented, created falsely, pretended; a lie; also, something wrapped in corn husks, such as a tamale

- michin = fish; abs. pl. mīmichtin. James Lockhart, Nahuatl as Written: Lessons in Older Written Nahuatl, with Copious Examples and Texts (Stanford: Stanford University Press and UCLA Latin American Studies, 2001), 225

The toponym (naming glyph) for Michoacán, “The place where there are (you have) fish”. Michoacán is responsible for 60% of Mexico’s production of the small fish known as charales (more on these little guys later).

One author (1) notes this evolution of the word emanating from the La Huasteca region (2). A derivation of the piktamali, a small triangular tamal made simply of masa. Linguistically Joel puts it like this “Piki by itself can be used as noun (usually with nonhuman prefix tla- as in tlapiki, tlaixpiktli, tlapictli ‘something wrapped’) for a corn dough cooked in corn leaves and in fact appears in local Spanish as piqui or pique, though these latter are frequently synonyms for epiki and epiqui, in which a bean paste is added to the dough (epiki starts with etl ‘bean’). A related word is tamalpiqui (tamalpic) ’to envelope a tamale in corn leaves to cook it’. Also I have seen this root in mextlapique, a tamale-relative with small fish (or tadpoles or frog legs), squash, tomato, onion, fresh corn kernels, chili, Chenopodium ambrosioides (3), cilantro, and sometimes cactus paddles, enfolded in leaves for roasting on a fire — mextlapique derives from Nahuatl michin (mich-) ‘fish’, tla- nonhuman prefix, and pīki ‘wrap’”

- https://tamaledigest.blogspot.com/2018/03/nahuatl-tamales-from-la-huasteca.html

- a geographical and cultural region located partially along the Gulf of Mexico and including parts of the states of Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Puebla, Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí, Querétaro and Guanajuato. It is roughly defined as the area in which the Huastec people had influence when their civilization was at its height during the Mesoamerican period.

- Chenopodium ambrosioides (syn Teloxys ambrosiodies; Dysphania ambrosioides) is the unique Mexican culinary (and medicinal) herb known as epazote. More on this herb further down.

The development of the naming of the dish likely evolves from tlapique to mextlapique when it contains fish (a specific one at that) and may in fact derive from the type of small fish also called meztlapique (1) used as an ingredient (Koerdell 1940).

- or mexcalpique, mesatlapique, mestlapique : Girardinichthys viviparus

also called Yacapitzahuatl

(Contreras-Balderas & Almada-Villela 1996)

These fish can also be known as charales

Others note however, on the naming of this dish that michtlapique is used to designate the fish tamale, and mextlapique for the tamale with any filling that is not fish.

In short, it is a dish that is wrapped in corn husks (totomoxtle) before being cooked. It does not have to contain fish as the names suggests.

Totomoxtle or hojas de maiz are the outer leaves that cover and protect the growing corn cob. They are a staple of Mexican cookery and can be found in ant Mexican grocery store. Here they are called hojas enconchadas. Enconchada comes from a root meaning of “withdrawing into one’s shell” or to “go into hiding”. This perfectly sums up what happens to the tamal and its filling when it is wrapped in the leaf before cooking.

Historically this dish was one of the lake dwelling peoples of the Basin of Mexico (the Xochimilca in particular) and, as well as fish, would have traditionally been made with ingredients such as ancas de rana (frogs legs), atepocates (tadpoles – also called renacuajos) and the meat of the waterdog (ajolote/axolotl). Many of these ingredients were in danger of being lost with the pollution of the remaining lakes and canals of Xochimilco and have been replaced with imported ingredients but there is no doubt that Mexicos indigenous peoples continued the tradition of using these ingredients and recent attempts at cleaning up the waterways of Xochimilcos chinampas have renewed interest in creating this dish from locally sourced ingredients.

Recipes for tlapiques collected in Mexico include the following varieties

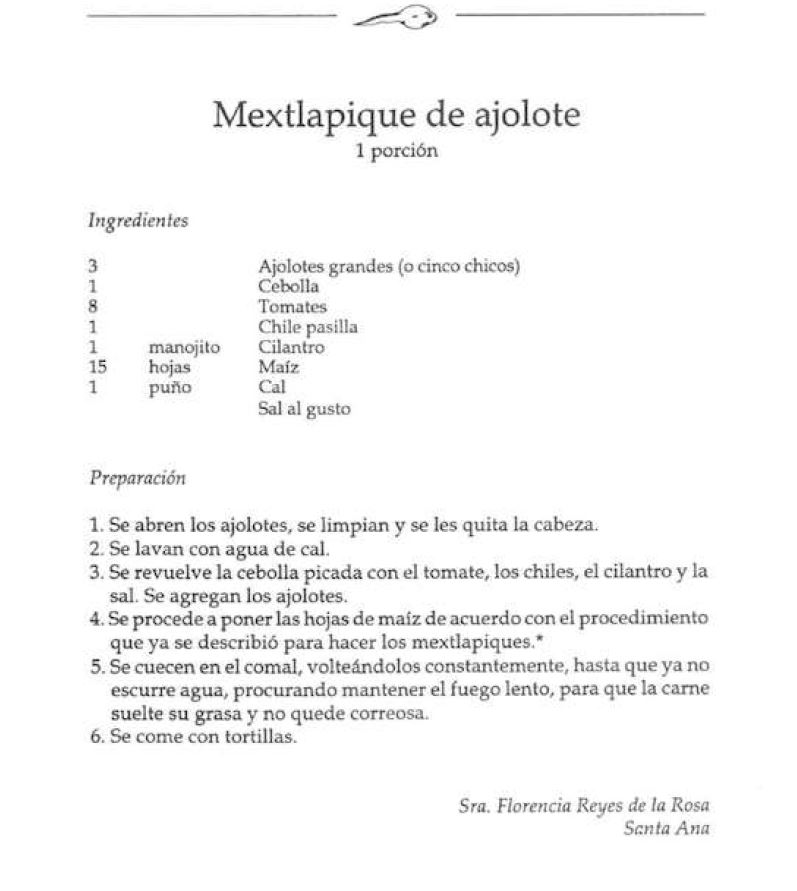

Mextlapique de ajolote (1)

Mextlapique de ancas de rana o atepocates (renacuajos)

What I know as a tadpole, which is the larval stage of various amphibians (frogs/toads)

Here is some in a green mole created from quelites

(including my favourite one of all, papalo)

Mextlapique de camarón (shrimp)

Mextlapique de charales (charales – a small white fish – similar to what I know as whitebait)

For more info on substitutions for this ingredient in Australia see the bottom of this Post)

Mextlapique de guajolote (turkey – a native of the Americas)

Mextlapique de huevas de pescado (fish roe)

Mextlapique de nopal (nopal cactus – you should know what this is by now I hope)

Mextlapique de pato (duck – waterbirds were commonly eaten in this part of the World) (Parsons 2005)

Mextlapique de pescado blanco (white fish)

- I have read that tlapiques of ajolote are currently banned due to the endangered status of the axolotl. I have yet to find a definitive source on this though.

Tlapiques cooked with local (and indigenous) ingredients might include the edible grasshopper known as chapulines.

The following varieties include ingredients that arrived with the Spanish

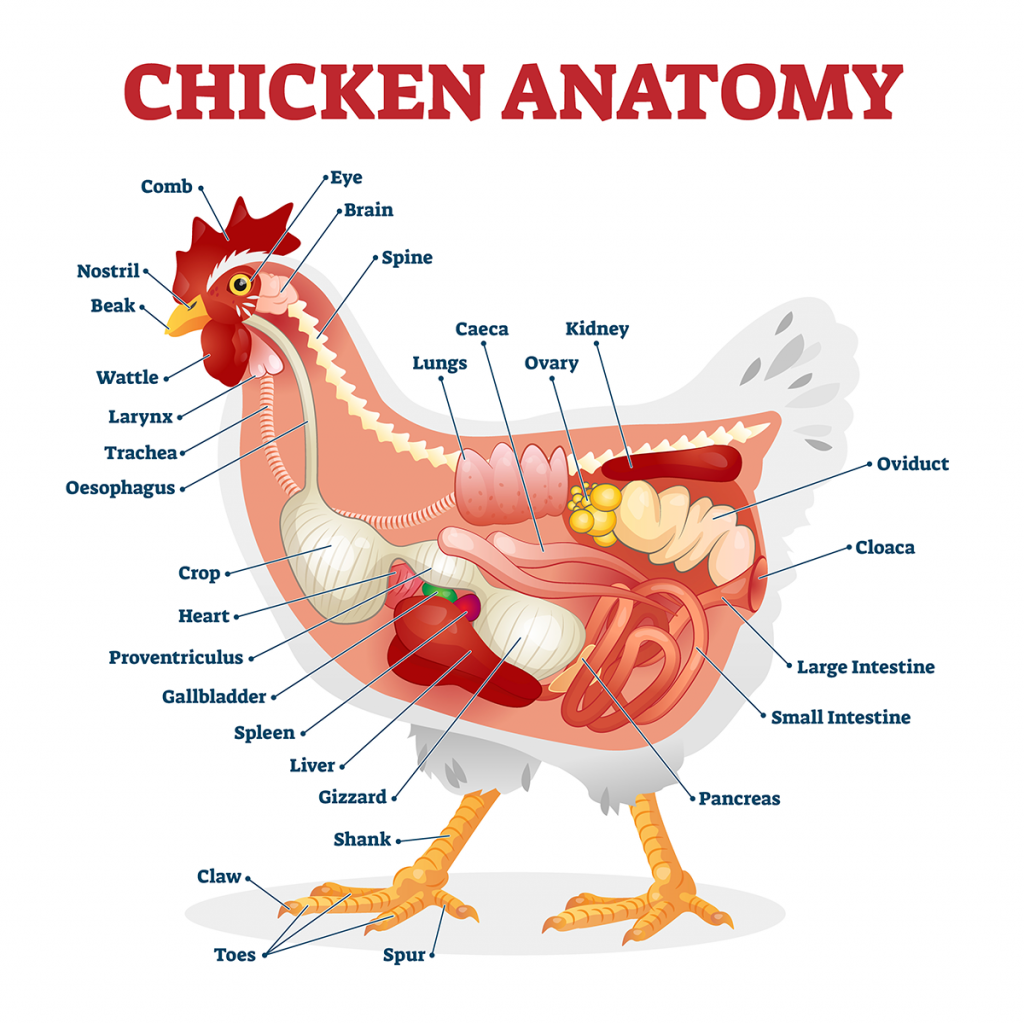

Mextlapique de mollejas (sweetbreads – the thymus gland of various animals – in this case veal (ternera) – these glands are located in the chest, in front of the trachea in the chest, just before the trachea. – although mollejas de pollo refers to the chickens gizzard)

(still a cow though)

Mollejas

Mextlapique de queso panela (a mild flavoured cheese made from cows milk)

Mextlapique de sesos (brains – likely sheep or cow)

Mextlapique de testículos de Marrano (pigs testicles)

Mextlapique de tripas (tripe – Tripas or machitos is a popular Mexican dish consisting of pig or cow intestines. They are cleaned, boiled and grilled and are an ingredient used in tacos. Outside of Mexico they might be known as chitterlings or chitlins)

How to cook them

Upon superficial observation a tlapique looks like a tamal. Closer examination will show that there is no masa used and that it is cooked on a grill over an open flame or on a comal heated over an anafre and not steamed as a tamal is.

Tlapiques are made with the same wrapping that tamales are made with and that is hoja de maiz (or totomoxtle) which are the dried outer leaves or husk of a corn cob. These leaves are soaked in clean water for 15 minutes or longer to make them flexible. Shake them dry to remove any excess moisture and they are ready to use. You will use more leaves to make a tlapique than are needed to make a tamal (which usually only needs one or two) so stack at least three leaves before filling and wrapping your tlapique. More leaves are needed as your tlapique will end up charred and burnt (although you don’t want them to catch fire) by the end of the cooking process.

Spread a layer of aromatic herbs in your hojas as a base and place upon this the filling of your tlapique. Wrap your tlapique with more hojas so that it is completely enclosed and tie it securely shut with some strips of the same hojas used to wrap it (although you could use wire as in the image below).

(this can be tricky if your totomoxtle is too dry)

tie them up with strips of your hojas

You don’t want it to fall apart during the cooking process. Place on a hot grill (or over coals – don’t cook over an open flame as you don’t want it to actually catch on fire) and turn occasionally so that it is cooked on all sides. All recipes I have found state that you’ll know when it’s done cooking as it will stop dripping liquid. This usually takes about 40 minutes.

The tlapique can be totally vegan if one desires. The recipe below contains nopalitos (cactus “leaves”) and xoconostle (sour cactus fruits from a relative of the nopal) which has been flavoured with the sharply hot chile de arbol and the pungent epazote herb.

Tlapique de Nopal

Serves 2

Ingredients

• 1 chile de arbol

• 1/2 teaspoon salt

• 2 xoconostle fruits

• 2 nopal pads (about the size of your hand)

• 2 sprigs of epazote (See**NOTES**)

• 3 dried corn husks (totomoxtle)

Method

- Soak the totomoxtle in hot water to soften them.

- Remove the spines from the nopal and rinse with a little water. Chop into small cubes.

- Peel the xoconostle with a small knife, cut in half, remove the seeds with a spoon and cut into small pieces.

- Chop the chili and the epazote leaves finely.

- Mix the cactus, xoconostle, chili and epazote with salt in a bowl.

- Drain the totomoxtle, open them well and arrange them so that they overlap a little. Fill with the mixture of nopales and xoconostle. Wrap well.

- Grill over low heat, turning occasionally to cook evenly. The tlapique is ready when it stops draining liquid.

**NOTES** : Epazote is a herb common in Mexican cookery. It is not as common in other countries due to its pungent and oft debated flavour (which is often compared to kerosene). The flavour is unique and persistent. I once ate a quesadilla of flor de calabaza, quesillo and epazote from a street vendor in Mexico City. It was the first thing I ate in the morning and every burp that I made that day tasted strongly of epazote. For a little more detail on this quelite check out Quelite : Epazote and Skunkweed and the Skunk

The Dalia Mercado Cultural

Dalia is a space created with all the love for Mexico and Xochimilco where you can come to partake of the best of Mexican cuisine. You can also visit their tienda and pick up some locally created artisanal products or participate in one of their latest workshops.

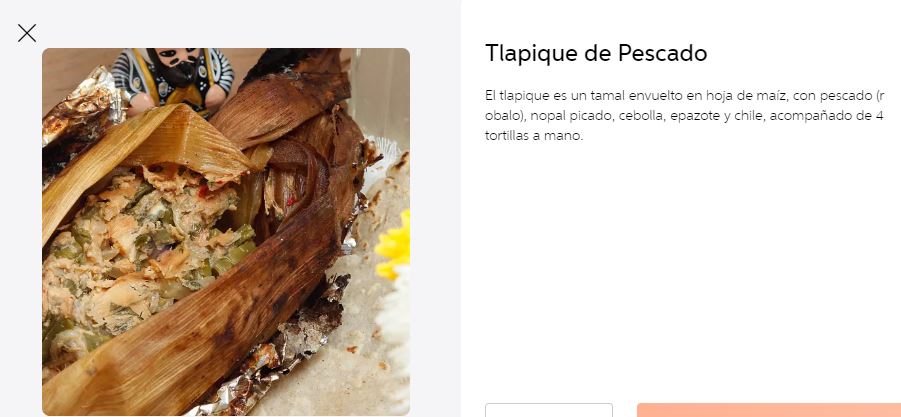

A selection of tlapiques from Dalias menu.

Charales can be substituted for a small white fish we call whitebait (in Australia and New Zealand). In N.Z. the Kiwis make fritters of this fish.

Ingredients

- 1 cup Fresh Whitebait

- 1 Egg

- 1 Slice Lemon

- Salt

- Pepper

- 1 heaped teaspoon of flour

For each cup of fresh whitebait mix together one beaten egg, and one heaped teaspoon of flour, salt and pepper to taste. Nothing else. Cook in moderately hot pan with a little butter to prevent sticking.

References

- Bedolla A. G. Vanegas J. E. & Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (Mexico). Centro Comunitario Culhuacán. (1990). La comida en el medio lacustre : culhuacán (1. ed.). Fideicomiso del Fondo de Participación Ciudadana para el Desarrollo Social en Iztapalapa : Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Unidad Iztapalapa ; Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Retrieved July 5 2023 from http://books.google.com/books?id=H8xQAQAAIAAJ.

- Contreras-Balderas, S. & Almada-Villela, P. 1996. Girardinichthys viviparus. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- González, Jorge Ortega & Pérez Rodríguez, Luis Alberto : (2022) Guía Gastronómica de las Ciudades Mexicanas Patrimonio Mundial : https://ciudadespatrimonio.mx/guiagastronomica/Guia_Grastronomica_de_las_Ciudades_Mexicanas_Patrimonio_Mundial.pdf

- Holguin, Fdo. (2019). The Mexicanness of Xólotl/Axólotl: Wonder of Literature and Gastronomy.. Mitologías hoy. 19. 147. 10.5565/rev/mitologias.622.

- Koerdell, Manuel Maldonado (1940) The life and work of don Miguel Bustamante y Septiem : Magazine of the Mexican Society of Natural History , Vol. I, No. 3, August, 1940 : Miguel Bustamanate y Septiem, “Description of the Mexclapique ( Cyprinus viviparus )”, Volume II of the Mexican Mosaic , p.116, printing house of Don Ignacio Cumplido, Mexico, 1837

- Luja, Alondra Almaguer. (2018) La herencia mexica de los ingredientes animales y las bebidas en la gastronomía Mexicana “The mexican heritage of animal ingredients and beverages in mexican gastronomy” Revista Conexxión de Hospitalidad y Gastronomía, Año 6, Número 15, (Mayo – Agosto 2018), pp. 18-30, ISSN: 2007-848X

- Parsons, Jeffrey R. (2005) The Aquatic Component of Aztec Subsistence: Hunters, Fishers, and Collectors in an Urbanized Society : Subsistence and Sustenance vol. 15, no. 1, 2005 : http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.0522508.0015.104

- Tate, C. E. (2009). The Axolotl as Food and Symbol in the Basin of Mexico, from 1200 BC to today. Pre-Columbian Foodways, 511–533. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0471-3_21

Websites

- https://laroussecocina.mx/palabra/mextlapique/

- https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/michin

- https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tlapictli

- https://recetariolagodetexcoco.org/Tlapiques

- https://www.animalgourmet.com/2021/01/20/tlapique-tamal-mexicano-sin-masa/?fbclid=IwAR3shwEr9IQoeoXYE5-r-xAMzdQEpHUoqTxIw57tpWn4g3kKtIDDnkaapPc

- https://www.imer.mx/rmi/de-saberes-y-sabores-el-tlapique-un-platillo-lacustre-de-origen-prehispanico/

Images

- Atepocates – Image via Chinampa Cultivando Comunidad-CCC on Facebook

- Chapultepec splitfin (Girardinichthys viviparus) Image by Juan Cruzado Cortés – https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/321628, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=107305566

- Charales – By Hinojosaz – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15891837

- Huevas de pescado (Nayarit caviar) image via https://gentenayarit.com/2020/05/19/hueva-de-pescado-el-caviar-nayarita/

- Lakes in the valley of mecico circa 1519

- Lambs brains : https://sutcliffemeat.com.au/product/lambs-brains/

- Mextlapique y Michtlapique image via Raul Aguilar on Facebook

- Michoacan toponym image via Kanakue TTK on Facebook

- Michwakan image via Tacámbaro De Mis Amores on Facebook

- Mole de Quelites image by Escuela de Gastronomia Mexicana via Facebook

- Mollejas de Ternera : https://www.casqueriasgonzalo.com/ : Casquerias Gonzalo lays claim to be the first website in the World (since 2007) to be entirely dedicated to offal. It is a highly informative website and contains many recipes worth investigating.

- Pig Testicles for Sale at my Butcher : Image by tangoking : https://www.reddit.com/r/mildlyinteresting/comments/npxwlw/pig_testicles_for_sale_at_my_butcher/

- Preparing and cooking your tlapique (6 images) via PIF Etnohistoria de la comida on Youtube

- Tlapique of frogs legs. Image from the Muestra Gastronómica de Xochimilco (Xochimilco Gastronomic Show) help in 2017 : https://revistacardinalia.wordpress.com/2017/03/23/invitan-a-muestra-gastronomica-de-xochimilco/

- Tlapique (wrapped with wire) image via Arte y Cultura Xochimilco on FB

- Tlapique con chapulines y habas (2 images) via PIF Etnohistoria de la comida on Youtube

- Tlapiques cooking in Xochimilco image via Club Tengo Hambre on FB

- Whitebait fritters image via Debra Cummings on Facebook