Abstract

In this article we present a case of a 35-year-old patient with a massive 43 × 35 × 34 mm cavernous venous malformation of the left orbit. The orbital lesion was initially observed in 2008 and remained untreated to 2021 due to the patient’s refusal to consent to the surgical procedure; which caused the tumor to grow to monstrous dimensions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A broad range of tumors and pseudotumors can be found in orbit. Most of them are benign. The frequency of malignant tumors increases with age because of the higher incidence of lymphoma and metastasis in the elderly [1]. The most common intraconal benign orbital pathological lesion in adults is a cavernous venous malformation, accounting for 5–9% of all orbital tumors [2,3,4,5]. Orbital cavernous venous malformations (CVMs), previously known as cavernous hemangiomas, are benign, non-infiltrative, slowly progressive vascular neoplasm composed of endothelial-lined spaces surrounded by a fibrous capsule. Most CVMs are located within the muscle cone and in the area of the lateral wall of the orbit. Poland’s average incidence of orbital tumors is approximately one new case per 100,000 people [6]. They can occur in both adults and children but usually, appear in middle age 3-5th decade and present slight female predilection due to expression of progesterone receptors in the epithelial cells of orbital CVMs [5, 7,8,9]. Histopathology of the tumor reveals a fine capsule surrounding a tumor consisting of large endothelium-lined channels with abundant, loosely distributed smooth muscle in the vascular wall and stroma [10]. CVMs grow by progressive enlargement of the thin-walled vascular channels, eventually causing clinical symptoms [11]. Treatment is not always required but is usually indicated due to the evident clinical manifestations or for facial aesthetic reasons [12].

Case Report

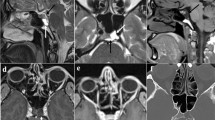

We present a case of a 35-year-old patient with moderate mental retardation, with a massive 43 × 35 × 34 mm retrobullar tumor of the left orbit. The tumor was primarily diagnosed in 2008; however, due to its relatively small size and poorly expressed symptoms—the patient did not consent to surgical treatment at that time. After nearly 13 years, on January 28, 2021, the patient was referred to the Emergency Department of the University Teaching Hospital in Wroclaw with significant exophthalmos of the left eyeball, preventing the closure of the eyelid fissure; with poor eyeball mobility, blurred vision, severe corneal ulceration and significantly impaired but preserved function of vision, which was limited to counting fingers from the distance of 30 cm. (Figs. 1 and 2). There was a displacement of all oculomotor muscles with anterior displacement of the globe (Figs. 3 and 4). (Fig. 5) The radiological and clinical manifestation suggested the diagnosis of cavernous hemangioma, schwannoma CNVI (Fig. 6), or left orbital meningioma. (Figs. 3 and 4) The tumor was completely removed by frontoorbitotomy from a bicoronal approach (Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14). Minimal bleeding was observed, the tumor was completely excised with relative ease due to its typical encapsulation and the lack of adherence to the surrounding tissue. Postoperative histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of cavernous hemangioma.

Three months after the operation, with the strict cooperation with ophthalmologists, proptosis with limited mobility had improved, but visual acuity was limited to counting fingers at 1.5 m in the right eye (Figs. 15 and 16).

The article presents diagnostic images (MRI), intraoperative images, an individual 3D model used at the planning stage of the procedure (Fig. 6), as well as the early and late treatment results.

Discussion

The orbital venous malformation is the most common finding in patients with slow-developing proptosis [13]. The incidence of CVM is approximately 0.1–0.8% in the general population [14, 15]. The diagnosis of orbital CVM can usually be established by combining CT scan, MRI, and ultrasonography [16]. CT-typically shows as a round or oval, well-defined intraconal mass with contrast enhancement. Hemangiomas locate most frequently in the central nervous system but can be found in different locations such as a liver, and—which is extremely uncommon—in the spinal cord, ribs, lungs, and spleen. extremely uncommon [14, 17,18,19,20]. Cavernomas are seen in sporadic or rare congenital and familial cases. Most of the CVMs are unifocal, although familial cases are predominant to develop more than one malformation. A higher rate of familial cases is reported in the Hispanic American population. They may grow or decrease in size over time [9, 15, 21,22,23,24]. The average annual rate of hemorrhage is reported at 0.15–1.1% in patients without a history of prior hemorrhage, and it is significantly higher after the episode of hemorrhage, reaching up to 2.7% [14, 21, 25]. Studies have noted that sclerotherapy could be a safe and effective treatment of orbital low flow vascular lesions such as CVMs [5, 26, 27]. Surgery is still the preferred treatment for this condition. The standard surgical approach to orbital CVM is lateral orbitotomy; however, anterior orbitotomy can be excised on smaller tumors, either transconjunctivally or transcutaneously or by endoscopic surgery [28, 29]. The tumor should be completely excised by surgery, and a long follow-up of these patients is recommended to monitor recurrence in case of incomplete excision [30, 31].

References

Shields JA, Shields CL, Scartozzi R (2004) Survey of 1264 patients with orbital tumors and simulating lesions: the 2002 montgomery lecture, part 1. Ophthalmology 111(5):997–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.01.002

Yan J, Wu Z (2004) Cavernous hemangioma of the orbit: analysis of 214 cases. Orbit 23(1):33–40

Henderson JW (1994) Orbital tumors, 3rd edn. Raven Press, New York, pp 95–100

Gaillard F, Luong D (2005) Orbital cavernous venous malformation, Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-9538

Kim MH, Kim JH, Kim SE, Yang SW (2019) Surgical outcomes of intraconal cavernous venous malformation according to their location in four right-angled sectors. J Craniofac Surg 30(6):1700–1705. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000005501

Pieńkowski P, Wieloch M, Golusinski W, Pazdrowski J, Łuczewski Ł (2012) Orbital tumors in material of department of head and neck surgery and oncological laryngology of greater Poland cancer center 2007–2010. Otolaryngol Pol 66(1):39–42

Lin E, Garg K, Escott E et-al (2008) Practical differential diagnosis for CT and MRI. Thieme Medical Pub, ISBN:1588906558

Müller-Forell WS, Boltshauser E (2005) Imaging of orbital and visual pathway pathology. Springer Verlag, ISBN:3540279881

Erdogan B, Sen O, Aydin VM, Yildirim T, Bircan S, Altinors N (2003) Multi-organ cavernous hemangiomas: case report. Neurol Res 25(1):92–94. https://doi.org/10.1179/016164103101200996

Rootman J (2003) Diseases of the orbit: a multi disciplinary approach. 2nd ed

Rosenblum B, Rothman AS, Lanzieri C, Sonc AS (1986) A cavernous sinus cavernous hemangioma case report. J Neurosurg 65:716–718

Bonavolontà G, Strianese D, Grassi P, Comune C, Tranfa F, Uccello G, Iuliano A (2013) An analysis of 2480 space-occupying lesions of the orbit from 1976 to 2011. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 29(2):79–86

Alfred PR, Char DH (1996) Cavernous hemangioma of the orbit. Orbit 15:59–66

Mouchtouris N, Chalouhi N, Chitale A, Starke RM, Tjoumakaris SI, Rosenwasser RH, Jabbour PM (2015) Management of cerebral cavernous malformations: from diagnosis to treatment. Sci World J 2015:808314. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/808314

Kim J (2016) Introduction to cerebral cavernous malformation: a brief review. BMB Rep 49(5):255–262. https://doi.org/10.5483/bmbrep.2016.49.5.036

Leng SZ (1991) Clinical analysis of orbital cavernous hemangiomas. Chung Hua Yen Ko Tsa Chih (Chin J Ophthalmol) 27:225–226

Isselbacher KJ, Dienstag JL (1994) Tumors of the liver. In: Isselbacher KJ, Braunwald E, Wilson JD, Martin JB, Fauci AS, Kasper DL (eds) Harrison’s principles of the internalmedicine, vol 2. Edition 13, McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 1495–1498

Mirhosseini SA, Ghanei ME, Zarepur E, Bidaki R (2018) Cavernous hemangioma of spinal cord: a clinical image. Clin Med Img Lib 4:113. https://doi.org/10.23937/2474-3682/1510113

Lovrenski A, Panjković M, Eri Z, Klem I, Samardzija G, Milić M (2011) Cavernous hemangioma of the lung. Med Pregl 64(5–6):327–30. https://doi.org/10.2298/mpns1106327l

Ghuliani D, Agarwal S, Thomas S, Pathania OP (2008) Giant cavernous haemangioma of the spleen presenting as massive splenomegaly and treated by partial splenectomy. Singap Med J 49(12):e356–e358

Zyck S, Grahame C (2022) Gould, cavernous venous malformation, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing

Dalyai RT, Ghobrial G, Awad I, Tjoumakaris S, Gonzalez LF, Dumont AS, Chalouhi N, Randazzo C, Rosenwasser R, Jabbour P (2011) Management of incidental cavernous malformations: a review. Neurosurg Focus 31(6):E5. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.9.FOCUS11211

Clatterbuck RE, Moriarity JL, Elmaci I, Lee RR, Breiter SN, Rigamonti D (2000) Dynamic nature of cavernous malformations: a prospective magnetic resonance imaging study with volumetric analysis. J Neurosurg 93(6):981–986. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.2000.93.6.0981

Fobe JL, de Lima JB, de Buone ML, CoreeaNeto J (1996) Familial cavernous angioma. Report in 3 generations. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 54:665–660

Kearns KN, Chen CJ, Yagmurlu K, Capek S, Buell TJ, Taylor DG, Pomeraniec IJ, Park MS, Kalani MY (2019) Hemorrhage risk of untreated isolated cerebral cavernous malformations. World Neurosurg 131:e557–e561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.222

Barnacle AM, Theodorou M, Maling SJ, Abou-Rayyah Y (2016) Sclerotherapy treatment of orbital lymphatic malformations: a large single-centre experience. Br J Ophthalmol 100(2):204–208. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306657

Schwarcz RM, Ben Simon GJ, Cook T, Goldberg RA (2006) Sclerosing therapy as first line treatment for low flow vascular lesions of the orbit. Am J Ophthalmol 141(2):333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2005.09.026

Yan J, Wu Z (2004) Cavernous hemangioma of the orbit: analysis of 214 cases. Orbit 23(1):33–40. https://doi.org/10.1076/orbi.23.1.33.28992

Lee RP, Khalafallah AM, Gami A, Mukherjee D (2020) The lateral orbitotomy approach for intraorbital lesions. J Neurol Surg Part B: Skull Base 81(4):435–441

Deng C, Hu W (2020) Multiple cavernous hemangiomas in the orbit. Medicine 99(29):e20670. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000020670

Bagheri A, Khandan S, Salour H, Aletaha M, Abrishami A (2012) Recurrent orbital cavernous hemangioma due to overlooked multiple tumors. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 7(3):244

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author’s declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jaxa-Kwiatkowski, A., Tomczyk-Kurza, K., Gerber, H. et al. Orbital Cavernous Venous Malformation in a 35-Year-Old Man: A Case Report. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 75, 1000–1005 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-022-03249-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-022-03249-0