(Note: the following post contains spoilers for Chrono Trigger: a Super Nintendo JRPG from 1995. If you haven’t played it, stop reading and go play it. No, seriously, go play it. Why are you still reading this? I can wait. It’s on Wii Virtual Console or, like, Android, for $10 or something, though apparently the Android version is based on the DS version, which is a good port though it adds some bonus dungeons that suck and makes Frog lose his King James accent, sadly. From this point on I’ll assume you’ve played it, as Chrono Trigger deserves to be in the general consciousness at least as much as, say, Star Wars does, if not more so.)

I’ve never made it a secret that Chrono Trigger is my favorite game of all-time. In fact, it is so good that for a long time it fooled me into thinking that JRPG’s were one of my favorite genres (that’s “Japanese Role-Playing Games” like the Final Fantasy or Kingdom Hearts series, as opposed to “Western Role-Playing Games” like Skyrim or Mass Effect which I actually do like a lot more in general). To this day I can count on one hand how many JRPG’s I actually enjoy, but Chrono Trigger stands head, shoulders, knees, and toes above all of them, maybe even on one of those pedestals on a hydraulic lift that can raise it even higher. And while there are about fifty kajillion reasons why (intriguing plots, time travel, cavewomen, a frog that speaks with an inexplicable Shakespearean accent, etc.), today I’d like to focus mostly on the razor-thin balancing act that is the protagonist of our story: a 17-year-old redheaded katana-wielding teenager with a single parent (and at least one cat) named Crono (so named because “Chrono” is six letters and the game only let you use five letters for names).

First, let’s provide come background information on RPG’s in general. Role-Playing Games are so named because you, in at least some small way, control how a certain character or characters develop. The level of control you have depends on the game, as does the amount of immersion into the role. For example, many modern-era JRPG’s have fully fleshed-out protagonists who have their own personalities and make their own decisions; you just basically tell them where to move outside of cutscenes and what attack moves to use in battles. This first type of RPG protagonist is barely immersive at all: you’re not supposed to identify with the character, you’re supposed to witness their story and maybe have a hand in some parts. Even in some stories where you have at least some control over their personality (such as Mass Effect where your choices boil down to choosing between “be a righteous hero” and “be a hero who’s kind of a jerk sometimes”), it’s still not your story. You just, as the player, have some influence on how it all plays out, and usually you have a lot more say in what skills/abilities you want the protagonist to develop than what kind of person you want them to be.

The second type of RPG protagonist is the one where the character you play is supposed to be your own surrogate. Games such as Skyrim, or most MMORPG’s, or pretty much any game where you craft a character at the beginning, fall into this category. Many of these games are based on a Dungeons and Dragons model, where you make up all your character’s attributes and personality traits, and while they can be immersive, it’s much more difficult to tell a wonderfully plotted, coherent story with good pacing and side characters, etc. More often these type of games end up being open-world sandbox games, where you can go around and do whatever quests you think your character would do (or whatever quests will get you the best rewards, if you care more about the gaming system than the role-playing aspect). Characters may react to your decisions, but usually only on a superficial level at best, so that all types of people can throw themselves into the protagonist role and not feel alienated by it.

There is a third type of RPG protagonist, however, that for lack of a better term is normally called the “silent protagonist.” This type of character is an attempt to blend the other two: the character still has a backstory and personality, but doesn’t actually say anything in order for the player to more closely identify with the character. A good example of this type of hero would be Link from the Zelda series (though whether or not that makes Zelda an RPG series is debatable, considering that you have no control over what kind of a person Link is or what he can do outside of “how many items/heart pieces/whatever you’ve picked up so far”), or Serge from Chrono Trigger‘s sequel Chrono Cross. This is a hard type of character to pull off, however; too much personality or backstory and it’s just the first type of protagonist that just happens to be inexplicably mute (and therefore the player doesn’t identify with them), but too little backstory or plot influence and the protagonist could virtually be played by a wet napkin with a sword and some magic spells, for all the importance they have on the story (and therefore the player doesn’t particularly want to identify with them, or if they do they’ve got to fill in all the gaps themselves). But the best example of this type of protagonist, and the one that most people hold up as the most triumphant representation of how to pull off this character, is, of course, Crono.

The reason Crono works so well as a protagonist is that he’s enough of a cypher to pull you in to his place, yet he has enough influence on both the plot and the characters that you really feel like you’re experiencing what he is. The stakes are high, people’s interactions with you feel genuine, and you honestly feel like you are the person who is in this spot. And they pull this off with one main genius technique that I love, which is: Crono is not the focus of this story. This is not Crono’s story. But Crono is the heart of the story. Let me explain with a few examples.

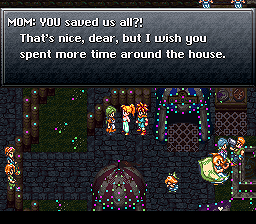

The game opens with Crono’s mom waking him up just in time for the local Millenial Fair (so called because we’re in 1000 AD), and reminds us that our childhood inventor friend Lucca has an exhibit there. That is literally the entire backstory we get for Crono, and it’s all revealed within the first minute of the game. He doesn’t end up being some sort of pre-destined hero with a prophecy about him, his dad isn’t revealed to be a long-lost knight or the Prince of Darkness or something, and his hometown isn’t even destroyed by the main villain. All we know is that he’s the kind of person who would be good friends with someone as awesome as Lucca (and make no mistake: she is awesome), which I think fills in the blanks pretty well. I’d say that most of us would love to be the type of person who would be good friends with someone like Lucca (and later on, the type of person that Marle would want to hang out at the fair with), so that’s one point for wanting to identify with Crono right there.

However, from the moment Crono runs into Marle at the fair, the game stops being about Crono, and, with two or three important exceptions, the game is never about Crono again. Oh sure, he’s still the protagonist, but the story doesn’t focus on him anymore. At the fair the focus becomes Marle’s wonderment at the fair, then Lucca and her invention, then saving Marle in 600 AD, etc. It’s really other characters making your decisions for you. But the game does it in such a way as to make you feel like you’re really deciding to do those things. It’s like the old adage that you can make someone do anything you want them to do, as long as you can figure out how to make them feel like they came up with the idea. For example, when Marle disappears into the past near the beginning of the game, you have to make the conscious decision to follow her. From a game perspective, it’s obviously the thing you need to (and Lucca won’t let you leave the screen until you do it, saying basically, “Hey, YOU brought that girl here, YOU help us get her back!”) but when you do it the characters in the game praise your decision so much (Lucca’s dad compliments you on being such a “fine lad,” and when you do end up finding Marle she can’t thank you enough, in a more personal way than the standard video game “Thanks for rescuing me! Here’s your reward of 200G!” or whatever) that the player begins to think, “Hey, yeah, that was pretty noble of me, wasn’t it?” Thus you identify with Crono more. Two points.

However, from the moment Crono runs into Marle at the fair, the game stops being about Crono, and, with two or three important exceptions, the game is never about Crono again. Oh sure, he’s still the protagonist, but the story doesn’t focus on him anymore. At the fair the focus becomes Marle’s wonderment at the fair, then Lucca and her invention, then saving Marle in 600 AD, etc. It’s really other characters making your decisions for you. But the game does it in such a way as to make you feel like you’re really deciding to do those things. It’s like the old adage that you can make someone do anything you want them to do, as long as you can figure out how to make them feel like they came up with the idea. For example, when Marle disappears into the past near the beginning of the game, you have to make the conscious decision to follow her. From a game perspective, it’s obviously the thing you need to (and Lucca won’t let you leave the screen until you do it, saying basically, “Hey, YOU brought that girl here, YOU help us get her back!”) but when you do it the characters in the game praise your decision so much (Lucca’s dad compliments you on being such a “fine lad,” and when you do end up finding Marle she can’t thank you enough, in a more personal way than the standard video game “Thanks for rescuing me! Here’s your reward of 200G!” or whatever) that the player begins to think, “Hey, yeah, that was pretty noble of me, wasn’t it?” Thus you identify with Crono more. Two points.

OK, so you arrive in 600 AD, though you don’t know what’s happened yet, and it’s apparent that Crono is just as confused as the player is, as most of the NPC’s in town are, like, “What are you talking about, ‘Millenial Fair?’ Shut your pie hole!” (the “pie hole” line is actually in the game). He reacts as any of us would, but it’s clear that the NPC’s are reacting to him and not just spouting generic lines for the most part (even though, technically, they are just spouting the same lines over and over). Throughout this part (and, indeed, most of the game, though it doesn’t approach this level of “WTF just happened to me?” until 12,000 BC), the player discovers what’s going on at the same rate as Crono, and at about the time you figure it out, people stop treating you like an idiot for asking dumb questions (this would be at about the time when you follow the clues to head to the castle to find Marle).

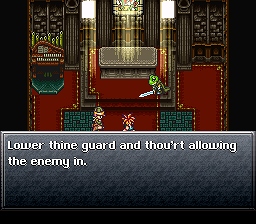

Sometimes the game is really subtle about having you make the right decision. For example, Frog’s introduction consists of him jumping out of nowhere and slicing a snake-woman in half, then uttering some immortally awesome lines like “Lower thine guard and thou’rt allowing the enemy in.” Lucca freaks out because he’s a frog and Frog responds, “My guise doth not incur thy trust… Very well, do as thee please. But I shall save the Queen.” Sure, it totally butchers the English language, but it lays out Frog’s awesome character really well. So on one hand you’ve got a really awesome swordsman (err….swordsfrog) whose goal is the same as yours, and on the other hand you’ve got your childhood friend who’s freaking out about it for the most superficial of reasons (she doesn’t like frogs). The game then asks you what to do. Once again, from a game perspective it’s obvious what you have to do (go with Frog), and the game doesn’t let you proceed until you do. But they could have easily done something a bit more lazy like have Frog appear in a tavern somewhere and say, “Thou seekest the Queen? I also hath taken it upon myself to fulfill such a noble quest! Let us joineth our forces,” or something equally butchered. The decision is still the same, but with this type of presentation your mind is made up by considering what would be best in the game (“taking this character would sure prove to be an advantage in the upcoming dungeon”). But the way the game actually portrays it, it’s Crono being the peacemaker and voice of reason (“Come on, Lucca, calm down. This frog guy looks competent, sounds awesome, and just chopped a snake woman in half! What better help could we ask for on our way to save the Queen?”). It’s subtle, but the game is putting you in Crono’s shoes to make this decision, as opposed to just having you the player make a sound gameplay choice.

Sometimes the game is really subtle about having you make the right decision. For example, Frog’s introduction consists of him jumping out of nowhere and slicing a snake-woman in half, then uttering some immortally awesome lines like “Lower thine guard and thou’rt allowing the enemy in.” Lucca freaks out because he’s a frog and Frog responds, “My guise doth not incur thy trust… Very well, do as thee please. But I shall save the Queen.” Sure, it totally butchers the English language, but it lays out Frog’s awesome character really well. So on one hand you’ve got a really awesome swordsman (err….swordsfrog) whose goal is the same as yours, and on the other hand you’ve got your childhood friend who’s freaking out about it for the most superficial of reasons (she doesn’t like frogs). The game then asks you what to do. Once again, from a game perspective it’s obvious what you have to do (go with Frog), and the game doesn’t let you proceed until you do. But they could have easily done something a bit more lazy like have Frog appear in a tavern somewhere and say, “Thou seekest the Queen? I also hath taken it upon myself to fulfill such a noble quest! Let us joineth our forces,” or something equally butchered. The decision is still the same, but with this type of presentation your mind is made up by considering what would be best in the game (“taking this character would sure prove to be an advantage in the upcoming dungeon”). But the way the game actually portrays it, it’s Crono being the peacemaker and voice of reason (“Come on, Lucca, calm down. This frog guy looks competent, sounds awesome, and just chopped a snake woman in half! What better help could we ask for on our way to save the Queen?”). It’s subtle, but the game is putting you in Crono’s shoes to make this decision, as opposed to just having you the player make a sound gameplay choice.

(Also, after he joins your party, the first thing Frog says is, “Mayhap a hidden door lurks nigh? Let us search the environs,” which is one of the most delightful lines uttered in a video game ever. It’s lines like these that make me prefer the SNES translation of the game to the DS one, which, while more accurate, left out Frog’s accent and made him a lot more bland.)

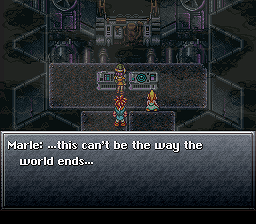

There are tons of little decisions like this sprinkled throughout the story that you feel like you’re influencing events more than you, as the player, actually are, which serve to draw you into the narrative through Crono, even though his influence on the plot is minor at best. Other characters make the important decisions: Lucca convinces you to save Marle, Marle takes you home, Marle makes the decision to run away and lead the party into the ruined future, Marle is even the one who actually makes the decision to save the world from Lavos and kick off the main plot, and most of the rest of the game is spent either solving other people’s problems, or accompanying them as they solve their own problems. Every playable character has their own story arcs and moments in the spotlight, and while some are better realized than others (I’m looking in your direction, Robo), they’re all nevertheless well-rounded, fleshed-out characters who drive this plot to many wonderful places that I won’t get into now. But absolutely none of these plot points (including the endgame of finally defeating Lavos) are about Crono at all. In fact, beyond the intro, the game is only about Crono two more times, but both of these times are important to distinguish Crono as a character beyond “nameless RPG protagonist like you’d create for Skyrim or something.”

There are tons of little decisions like this sprinkled throughout the story that you feel like you’re influencing events more than you, as the player, actually are, which serve to draw you into the narrative through Crono, even though his influence on the plot is minor at best. Other characters make the important decisions: Lucca convinces you to save Marle, Marle takes you home, Marle makes the decision to run away and lead the party into the ruined future, Marle is even the one who actually makes the decision to save the world from Lavos and kick off the main plot, and most of the rest of the game is spent either solving other people’s problems, or accompanying them as they solve their own problems. Every playable character has their own story arcs and moments in the spotlight, and while some are better realized than others (I’m looking in your direction, Robo), they’re all nevertheless well-rounded, fleshed-out characters who drive this plot to many wonderful places that I won’t get into now. But absolutely none of these plot points (including the endgame of finally defeating Lavos) are about Crono at all. In fact, beyond the intro, the game is only about Crono two more times, but both of these times are important to distinguish Crono as a character beyond “nameless RPG protagonist like you’d create for Skyrim or something.”

Let’s take the first moment: the trial scene near the beginning of the game. After the diversion to 600 AD to save both Marle and Queen Leene, you go to the castle in the Present to take Marle home (as a side note: I love how absolutely nothing pertinent to world history occurs in the Present. It just happens to be the time period where Crono, Marle, and Lucca are from, and the only plot that happens there (then?) relates to specific character arcs, not to the main “saving the world” plot.), and, as a result, get put on trial for kidnapping the Princess (Marle) by the chancellor. This sequence is brilliant for a lot of reasons, but for our purposes it puts the player once more squarely in Crono’s shoes. You see, no matter what the outcome of the trial is, the game afterwards continues exactly the same (plus or minus a few healing items you get in prison). So the game designers found an opportunity to make your choices at the beginning of the game actually have consequences without derailing the plot, and by framing it in this giant showpiece of a trial, they inflated their importance to make you, the player, take it seriously.

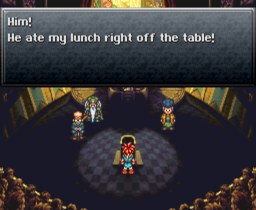

Crono’s guilt (or innocence) is based entirely on seemingly inconsequential actions taken during the very first part of the game, when you’re at the Millenial Fair. During this part of the game, most players are still new to the game and most probably treating it like any other RPG, where you go everywhere, interact with everything, talk to everyone, and generally collect loot while getting to know the world, following the general adventure game/RPG advice “Take everything that isn’t nailed down or too heavy (and anything that can be pried loose is not considered nailed down).”

Crono’s guilt (or innocence) is based entirely on seemingly inconsequential actions taken during the very first part of the game, when you’re at the Millenial Fair. During this part of the game, most players are still new to the game and most probably treating it like any other RPG, where you go everywhere, interact with everything, talk to everyone, and generally collect loot while getting to know the world, following the general adventure game/RPG advice “Take everything that isn’t nailed down or too heavy (and anything that can be pried loose is not considered nailed down).”

In most games this type of behavior has no influence on the story or gameplay other than item/information collection or mandatory plot advancement, or if it does it’s immediately apparent (for example, stealing will immediately set guards after you or something). But all the evidence brought up in the trial is based in things that you did during that beginning sequence, from good (e.g. helping a girl find her lost cat), to bad (e.g. eating a guy’s lunch when his back is turned) — things that most players did without even really thinking about it. Nothing is brought up that you didn’t have a hand in: nothing from Crono’s backstory, or from cutscenes that you didn’t have control over (except maybe when Marle got sent to the past, but even then you were the one that brought her there). In essence, you are put on trial, not just Crono, and the sentence directly involves your character and your actions. And directly afterward, when you get sent to jail, you get to decide whether or not to try to escape, or wait for your execution (that Lucca breaks you out of). This is the only dungeon in the game, by the way, that has this type of branching path: every other dungeon offers only one ultimate way through it. And it’s also the only dungeon in the game that Crono can do alone. To repeat: the only dungeon where you get to decide how to tackle it is the only dungeon that stars a solo Crono…i.e. you. How many points are we at on the “you are Crono” meter, again?

That pales, however, to the magnificence that is the Ocean Palace disaster and its aftermath. This is where serious Chrono Trigger spoilers come into play, and if you’ve read this far without playing the game, then I’m dead serious: stop reading now and go play this game! Are we good? Good.

Let’s fast-forward the game to 12,000 BC, just after the party has rescued Melchior from the floating Mt. Woe. (I told you to go play the game. Now you’re probably totally lost if you didn’t.) Schala comes to the gritty Earthbound village to plead with you to stop her mother from awakening Lavos and killing everyone in order to achieve ULTIMATE POWERTM. Unfortunately, she then gets forcibly taken by Dalton to go to her mother to help her kill everyone (why do people love Schala again? You’d think she’d just say “no” or something. I know it’s her mother, but it’s the fate of the world at stake! Grow a backbone, woman!), and Melchior laments that all life is doomed now. Crono, however, steps forward and shakes his head “no” (since he doesn’t talk and all). Melchior asks, “You’re willing to challenge the queen?” and Crono nods “yes” while Crono’s theme song (AKA the main Chrono Trigger theme) blares in the background. This is significant. In every other instance after the trial, the plot has been forwarded by somebody else saying, “we should do this!” whether it be another party member like Lucca or an NPC. This is the very first time since the Millenial Fair at the beginning that the game has actually had it be Crono that makes the decision to save the day. And since the game has been subtly manipulating the player into Crono’s shoes throughout the whole game, it really feels like a defiant and heroic moment, not just for Crono and the party, but for the player as well. However, this is made even more significant by the events that follow, in what is probably one of the best (if not the best) scenes in video game history.

Let’s fast-forward the game to 12,000 BC, just after the party has rescued Melchior from the floating Mt. Woe. (I told you to go play the game. Now you’re probably totally lost if you didn’t.) Schala comes to the gritty Earthbound village to plead with you to stop her mother from awakening Lavos and killing everyone in order to achieve ULTIMATE POWERTM. Unfortunately, she then gets forcibly taken by Dalton to go to her mother to help her kill everyone (why do people love Schala again? You’d think she’d just say “no” or something. I know it’s her mother, but it’s the fate of the world at stake! Grow a backbone, woman!), and Melchior laments that all life is doomed now. Crono, however, steps forward and shakes his head “no” (since he doesn’t talk and all). Melchior asks, “You’re willing to challenge the queen?” and Crono nods “yes” while Crono’s theme song (AKA the main Chrono Trigger theme) blares in the background. This is significant. In every other instance after the trial, the plot has been forwarded by somebody else saying, “we should do this!” whether it be another party member like Lucca or an NPC. This is the very first time since the Millenial Fair at the beginning that the game has actually had it be Crono that makes the decision to save the day. And since the game has been subtly manipulating the player into Crono’s shoes throughout the whole game, it really feels like a defiant and heroic moment, not just for Crono and the party, but for the player as well. However, this is made even more significant by the events that follow, in what is probably one of the best (if not the best) scenes in video game history.

So Crono and company head back to Zeal and use the transporter to head into the Ocean Palace to stop the Queen from awakening Lavos and destroying everything. However, they are too late, and despite your best efforts, Lavos is summoned. This is the first sucker punch to the player’s gut of several that happen during this scene. The epic battle against the ultimate horror that is Lavos begins… and he immediately KO’s the party without so much as breaking a sweat. Punch number two. Then the mysterious prophet appears…and is revealed to be Magus! What? Punch number three! He’ll finally have his revenge on Lavos, which he has been planning for years! It proves entirely ineffective, and the #2 antagonist of the game, who is also one of the most powerful mages in all of history…is taken out by Lavos almost as an afterthought. That’s number four! Already this sequence has been a powerful one in showing just what Lavos is capable of and how screwed everyone else is.

So what happens next? Crono, who has already been KO’ed once by Lavos, when he was still at full strength and had his party backing him up, rises to his feet, beaten and battered and all alone. At this point, you control only Crono. The other members of your party don’t get up. Magus doesn’t get up. Schala, who is also there, doesn’t get up, The Queen, who is perched on top of Lavos, just laughs at you. But you do the only thing you can do: try to fight on. Your party members scream at you, saying there’s nothing you can do; give up now. But you know you’ve gotta win, or at least do enough damage to be able to retreat and regroup or something. But no, Lavos screams and shoots a beam at you or something, and you literally melt into nonexistence. Crono is dead.

So what happens next? Crono, who has already been KO’ed once by Lavos, when he was still at full strength and had his party backing him up, rises to his feet, beaten and battered and all alone. At this point, you control only Crono. The other members of your party don’t get up. Magus doesn’t get up. Schala, who is also there, doesn’t get up, The Queen, who is perched on top of Lavos, just laughs at you. But you do the only thing you can do: try to fight on. Your party members scream at you, saying there’s nothing you can do; give up now. But you know you’ve gotta win, or at least do enough damage to be able to retreat and regroup or something. But no, Lavos screams and shoots a beam at you or something, and you literally melt into nonexistence. Crono is dead.

You’re dead.

But the game continues.

Schala uses the last of her power to get Magus and the other two party members to safety. Lavos erupts from the Ocean Palace and destroys the Kingdom of Zeal and basically the entire world. There are maybe ten to twenty people left on the entire planet. The remaining two members of your party wake up in the last village left, guarded by the pendant that Crono was holding for Marle but that he gave up right before he died. This is all told in cutscene, and this whole time you, the player, are probably hoping that, OK, now you’ll switch to Crono, who didn’t actually die but got sent to another time or dimension or something, and you’ll have to do some sort of solo dungeon or something to rejoin the rest of your party.

Then the ultimate punch lands.

The gameplay punch.

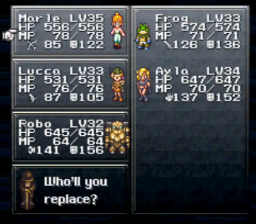

The “choose who you want to be in your party” screen comes up, and Crono (who up until now was permanently the first party member)…doesn’t show up in the menu.

This is the saddest moment in gaming history.

…

So let’s talk about this for a minute. First off, the pacing in this sequence is absolutely brilliant. The climax builds with such an energy of hopelessness, but yet, spurred on by that one moment from earlier when Crono himself agreed to save Schala and the Queen and his theme music blared, you still hold out that sliver of hope (that, and you know the game’s not gonna have a downer ending, I mean, come on!). But, after Crono dies, everything quickly goes south. The “Lavos erupts from the ground” animation, previously only seen in 1999 AD (also know as the freakin’ Apocalypse time period), is used here to destroy Zeal, which then crashes into the ocean and causes a giant tidal wave. The destruction of Zeal and its aftermath has no music playing; just a giant crash, followed by the sound of water rolling out in a wave, on a totally black screen (which I argue is more effective than even the prettiest rendering with today’s graphics would be). It allows the player to finally breathe and relax after this huge sequence, and it also allows all the facts of what just happened to sink in. Then, after the most dramatic moment of the entire game, you get kidnapped by the comic relief villain Dalton and you go through this silly little segment aboard the Blackbird, where a boss runs away because he’s afraid of heights, and Dalton gets mad because the wrong theme music is playing, and you even have the chance to pull the old “help my cellmate is sick open the door!” routine, which gets especially silly if, say, Robo is the one to do it.

This sequence helps not only relieve the tension of everything that just happened, but it finally gives the party an unequivocal victory: an out-and-out villain is defeated, the team gets a flying time machine, and there was a lot less at stake. (Consider that this is the first outright victory the party has had for a while: the last major dungeon before the Ocean Palace was the Tyrano Lair, where an entire species got wiped out by Lavos, and before that Magus’s Castle, where you stopped Magus from waking up Lavos but didn’t actually defeat him.) What’s more, it gets the player used to operating without Crono as the main character. It, in essence, helps you realize that, despite the game putting you squarely in the role of Crono and then killing him off, the game continues. The story continues. Because the game isn’t about Crono. The game isn’t about you.

It’s bigger than that.

But even though you’re not really important by birthright, or by circumstance, or even by tragic backstory, you are important through the choices you’ve made and the people you’ve influenced. It’s at this point in the game where the plot virtually stops because the party wants to get Crono back. Marle especially (since she’s the romantic lead and all), but Lucca too, and everyone else to lesser extents. What’s especially brilliant about this is that you don’t have to save Crono. At all. You can just go ahead and defeat Lavos now, or do some endgame sidequests to prepare yourself and then defeat Lavos. The world can be saved without Crono, as long as those left can finish what he started.

However, the game really pushes you toward saving him, and I don’t think anyone didn’t save him on their first playthrough. The sequence is appropriately epic yet at the same time personal: breaking all the laid-out rules of time travel thus far and climbing a post-apocalyptic mountain filled with Lavos’s offspring, yet involving winning a doll from the fair and talking to Crono’s mom (which you don’t have to do at all after the first minute of the game up until now). And it’s an emotionally wrenching scene when you finally do save him (you go back to the frozen moment in time where he died and switch him out for the doll that looks like him), especially if you bring Marle or Lucca along, but I especially appreciate the fact that, if you don’t bring either of those two, whoever’s in the party is basically all, “Hey, cool, Crono’s back; now can we get on with saving the world, please?!?” Because, once again, Crono’s not important. None of the endgame sidequests involve him at all, and you don’t even have to use him even if you do bring him back from the dead (though you should: he’s still probably the best character in the game in terms of combat). And if you do use him, you can throw him back to the second or third character spot, which you couldn’t do before, and in fact must do in some of the sidequests (some, such as Robo’s, require that particular character to be in the first party member slot). He’s not the protagonist anymore, and he’s barely even in the game at this point. The player has hopefully moved beyond identifying solely with Crono and is able to look at the world and other characters through different eyes now.

However, the game really pushes you toward saving him, and I don’t think anyone didn’t save him on their first playthrough. The sequence is appropriately epic yet at the same time personal: breaking all the laid-out rules of time travel thus far and climbing a post-apocalyptic mountain filled with Lavos’s offspring, yet involving winning a doll from the fair and talking to Crono’s mom (which you don’t have to do at all after the first minute of the game up until now). And it’s an emotionally wrenching scene when you finally do save him (you go back to the frozen moment in time where he died and switch him out for the doll that looks like him), especially if you bring Marle or Lucca along, but I especially appreciate the fact that, if you don’t bring either of those two, whoever’s in the party is basically all, “Hey, cool, Crono’s back; now can we get on with saving the world, please?!?” Because, once again, Crono’s not important. None of the endgame sidequests involve him at all, and you don’t even have to use him even if you do bring him back from the dead (though you should: he’s still probably the best character in the game in terms of combat). And if you do use him, you can throw him back to the second or third character spot, which you couldn’t do before, and in fact must do in some of the sidequests (some, such as Robo’s, require that particular character to be in the first party member slot). He’s not the protagonist anymore, and he’s barely even in the game at this point. The player has hopefully moved beyond identifying solely with Crono and is able to look at the world and other characters through different eyes now.

This even extends to the endgame after defeating Lavos, which, while it begins with Crono waking up again, eventually moves to the last night of the Millenial Fair. The only controllable part of this section has Crono and Marle walking around the fair talking to various people, and interestingly enough, you’re actually controlling Marle, with Crono following behind: a reversal of the beginning of the game. The cycle is complete, and you can now leave the world of Chrono Trigger in the hands of the characters who inhabit it.

This even extends to the endgame after defeating Lavos, which, while it begins with Crono waking up again, eventually moves to the last night of the Millenial Fair. The only controllable part of this section has Crono and Marle walking around the fair talking to various people, and interestingly enough, you’re actually controlling Marle, with Crono following behind: a reversal of the beginning of the game. The cycle is complete, and you can now leave the world of Chrono Trigger in the hands of the characters who inhabit it.

So what does this 5,000-word essay amount to in the end, other than the fact that I really really love this game? Firstly, it amounts to the fact that Crono really does embody the best of all RPG protagonist types. The story is focused and character-driven, like the first type of protagonist, yet you’re put squarely in Crono’s shoes and can’t help but identify with him, like the best examples of the second type. Secondly, it shows the masterful work involved in sucking the player into a storyline that is so carefully crafted that you can kill off the main character 2/3rds of the way through and have it be an emotional moment, instead of a “oh, come on!” moment. But most importantly, I think it teaches some life lessons that I kind of summed up in this post’s title but would like to reiterate.

Everyone is the protagonist of their own story. But most fictional stories have a protagonist who is the focal point of the story or a sideline observer who’s just the storyteller. And so most people, in real life, tend to think of themselves as one or the other: either the most important person simply because they exist, or some nobody that doesn’t really influence much. Just because we’re not a “chosen one,” or the focal point of the world, or even anyone famous, doesn’t mean that we don’t have the power to change the entire world, if we can find the right way to do it and get the right people to support us. Or better yet, find the right people to support. Lucca and Marle aren’t supporting Crono; Crono is supporting Lucca and Marle (and Frog, and Robo, etc.) You don’t have to be the most important person in the world, or even in your own circle of acquaintances, to be the most important person in the world to at least one or two other people.

The game’s not about you. But you choose how it ends.

“It’s really other characters making your decisions for you. But the game does it in such a way as to make you feel like you’re really deciding to do those things. It’s like the old adage that you can make someone do anything you want them to do, as long as you can figure out how to make them feel like they came up with the idea.”

You know, I never noticed that about the game before, but it really does!

“For example, Frog’s introduction consists of him jumping out of nowhere and slicing a snake-woman in half, then uttering some immortally awesome lines like “Lower thine guard and thou’rt allowing the enemy in.”

All intros should involve slicing a snake-woman in half. Then spouting something pseudo-Shakespearean.

Well done, Jeff. I finally finished reading this. Now you can “go ape.”

Pingback: New blog! | Jeff's New Blog

Pingback: Crazy Bachelor | Jeff's New Blog

Pingback: My Career Crossroads: a Pandemic-forced Mid-Life Crisis. Part 4: Miscellanous Jobs and At Least One Decision | Jeff's New Blog

Pingback: New blog! | Part of Me