In early 1984, IBM released a computer called the PCjr. It was an attempt to create a low-cost entry-level version of the company’s expensive, business-oriented PC that would be cheap enough to gain IBM a place in the home computer market, then dominated by the Apple II, the Commodore 64 and the Atari 800 computers. It was expected to be a huge hit.

The PCjr. It never grew up.

Only it wasn’t. It flopped. Big time.

Although it was in some ways software compatible with its big brother, which in two-and-a-half years had taken over the microcomputer market the way Hitler had taken over Poland in the late 1930s, the PCjr’s compatibility had been seriously crippled to prevent it from competing with IBM’s more expensive, grown-up models. Very few existing PC programs would run on it and almost none of the ones that people might actually want to use would. But it did have one feature that made it superior to IBM’s business models: state-of-the-art (by 1984 standards) 16-color graphics and impressive sound capabilities, with no add-on cards required. The PCjr was made for games, though unfortunately it wasn’t priced at game console rates.

And because it was made for games, IBM wanted games available for it when the product launched. They approached several companies about designing games that would take advantage of the PCjr’s flashy hardware and one of these companies was Sierra On-Line, the same company that had popularized if not quite invented the microcomputer adventure game with Mystery House on the Apple II. And since Mystery House had been the first game to combine graphics with adventure game mechanics, perhaps its designer Roberta Williams, along with the technical staff of Sierra On-Line, could create something far more ambitious that would take advantage of the Junior PC’s much superior video display.

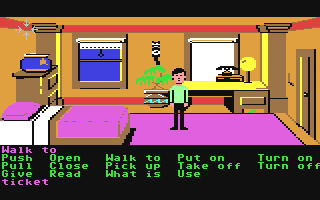

The game they produced, King’s Quest, delivered on that promise. Unlike previous graphic adventures, King’s Quest didn’t use the bottom half of its screen for text and the top half for a static image, like a page out of a children’s book. King’s Quest looked more like a proscenium stage on a computer screen, with colorful scenery and characters that could be guided through that scenery using the PC’s cursor keys. You still had to type commands using simple phrases a la The Colossal Cave Adventure, but you could actually see the results played out on the screen as though you were watching (and directing) a play.

King’s Quest. It may not look much now, but in 1984 this was the pinnacle of high-resolution adventure gaming.

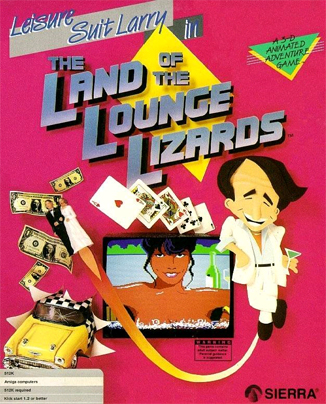

The PCjr may have flopped — by the summer of 1985 IBM was stuck with a warehouse full of unsold models — but King’s Quest didn’t. Sierra went on to release eight games in the series for multiple computers, many of the later games modifying the interface so that the player no longer had to type in commands. So successful were the King’s Quest games that they spawned several similar Sierra game series, including Space Quest, Police Quest, Quest for Glory (an adventure game-RPG hybrid) and Leisure Suit Larry (a more sophisticated implementation of an early Sierra text game called Softporn Adventure).

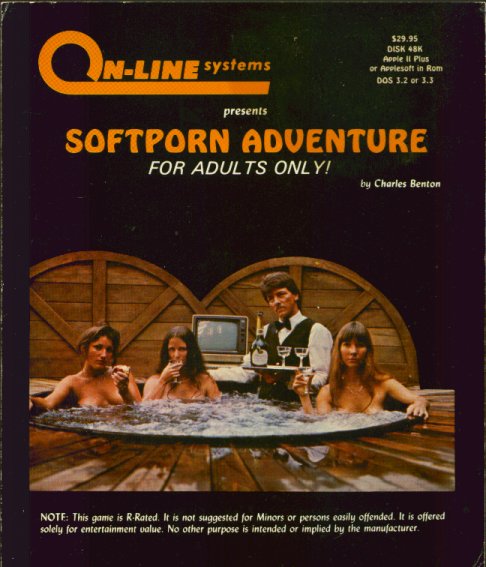

Softporn Adventure. Although she didn’t write it, that’s Roberta Williams, wife of Sierra publisher Ken Williams and designer of King’s Quest, on the right. This subsequently became…

…this. Yes, it was sleazy and included both bawdy humor and graphic sex. Nobody complained.

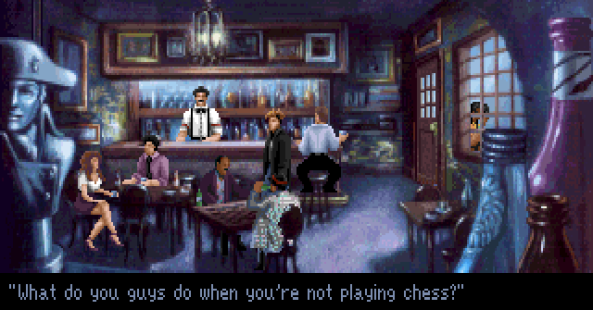

As computer power increased and audiences demanded more bang for their video game buck, Sierra complied, upping the visual resolution and number of colors as a new generation of home computers arrived on the market. The sophistication of the games increased too, with some fans regarding Jane Jensen’s Gabriel Knight series as some of the greatest adventure games of the 90s, at least from Sierra. (Confession: I’ve only played the first half of the first Gabriel Knight game, so I have to take the word of others for its superiority.)

Gabriel Knight: Apparently not interested in a high-stakes game of chess.

I’ll admit my bias against Sierra here. Although their adventure games were impressive by the technical standards of the time, the puzzle-solving was unimaginative, characters could be killed off suddenly and arbitrarily in ways that were far more frustrating than fun, and you could often find yourself locked in dead-end situations from which the game could not be completed, even though you were never informed of this. It was possible to spend days trying to solve a problem in a Sierra adventure only to discover that it was unsolvable because you’d neglected to pick up a screwdriver four scenes earlier in a location to which you could no longer return.

And yet Sierra had the legitimate distinction of creating a style of adventure gaming that revolutionized the field and saved it from the fate of text adventures in the mid-1980s. Furthermore, their proscenium-style adventures were widely imitated by other companies. And while many of the imitations, from companies like Accolade and Activision, were roughly comparable to Sierra’s titles, there was one company that took the concept and turned what at Sierra had been run-of-the-mill if technologically advanced games into masterworks of late 20th century computer gaming.

Yes, that’s my bias. And the rest of this post will be about it.

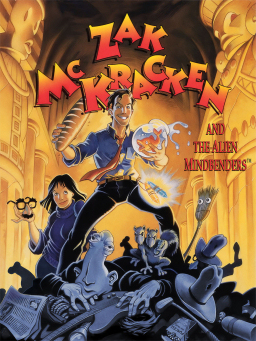

The Age of LucasArts

In 1987 Lucasfilm Games, later LucasArts, released a graphic adventure called Maniac Mansion. It was similar to the Sierra adventures, except that it ran on the Commodore 64, which is where I first encountered it. It was a parody of low-budget horror films and, to be honest, I can’t even remember if I bought a copy when it first came out. I found myself drawn more to Lucasfilm Game’s second adventure, the 1988 Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, which I found surprisingly engrossing, much more so than the Sierra adventures I’d encountered up until that point. Zak McKracken had a subtlety of wit and puzzle design that made Sierra adventures look as though they’d been designed by sledgehammer. I was enthralled.

Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders cover at by Steve Purcell. Copyright (c) 1988 by LucasArts, now a division of Disney.

This is not to suggest that Zak McKracken was any kind of technological marvel. Perhaps to allow it to run on lower end machines than those targeted by Sierra, the graphics seemed fairly flat and crude, even by the standards of the late 1980s. (More advanced versions of this and Maniac Mansion were published a couple of years later for more powerful machines.)

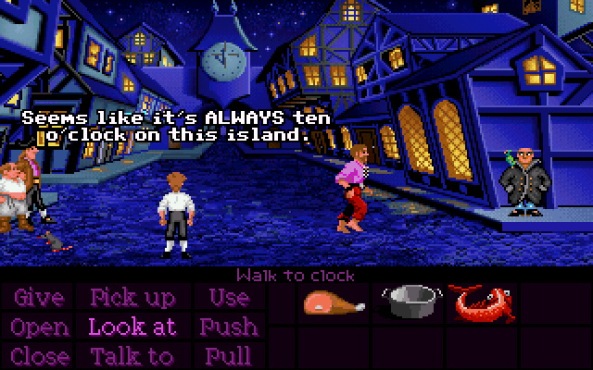

Screen from Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders. Note the menu-driven control system that eliminated the need for typed commands. Copyright (c) 1988 by LucasArts.

But the strength of Zak McKracken as an adventure game was its wit. The interactions between Zak and other objects/characters in the game, even the timing with which dialog appeared on the screen (there was no voice acting in the game), suggested a creative sensibility that placed less emphasis on the kind of expensive programming skills that Sierra brought to bear on its games and more on an intuitive sense of what was funny, what was challenging, and ultimately on what was compelling to the player. I found myself enthralled.

LucasArts made rapid leaps forward over the next two or three years with their games for the Atari ST, the Commodore Amiga and DOS PCs, games like Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (based on the film) and Loom (an innovative adventure that incorporated music into its problem solving). For me, though, the real breakthrough, the game that showed me just how much quality LucasArts was capable of shoveling into the confines of the graphic adventure format, was The Secret of Monkey Island, a game that remains available in updated versions even today. You can even buy it for your iPhone.

I knew that Monkey Island, about a young wannabe pirate named Guybrush Threepwood trying to discover the eponymous secret of the eponymous island, was going to be good when I spent a couple of hours working my way through the playable demo that LucasArts made available online. How good it was, though, wasn’t apparent until I bought the complete game and played it nonstop for two days.

The Secret of Monkey Island, when LucasArts adventure games went from being good to being great.

Monkey Island wasn’t just the funniest adventure game I’d played up until that time — I still laugh over the three-headed monkey joke — but had the most ingeniously designed puzzles (always fair and just challenging enough not to be frustrating), characters I actually enjoyed spending time with (including not only Guybrush but Governor Elaine Marley and the ghost pirate LeChuck) and a surprisingly effective romantic subplot. And the soundtrack, even on a PC SoundBlaster card, was possibly the best I’d heard up to that point in a computer game.

The Secret of Monkey Island was followed by a string of sequels (Monkey Island 2, The Curse of Monkey Island and Escape from Monkey Island), but also by a raft of LucasArts games that at least equaled if not surpassed the Monkey Island games in quality. These included Sam & Max Hit the Road, The Dig, Full Throttle, Grim Fandango and the Maniac Mansion sequel Day of the Tentacle, any one of which has a legitimate claim not only to being the greatest LucasArts adventure but the greatest adventure game ever. (My vote is with Day of the Tentacle, which was such an insanely epic comedy adventure that it contained a complete, playable version of Maniac Mansion hidden inside it as an Easter egg, but other gamers will inevitably differ.)

The tentacles have their day.

The second half of the 1990s, though, saw the output of LucasArts adventures slow to a trickle. Escape from Monkey Island, published in 2000, was the last original adventure game from the company, despite promised sequels to Sam & Max Hit the Road and Full Throttle.

Other than a few new adventures imported from the European market, this was pretty much the death of the adventure game on the American scene, amateur interactive fiction notwithstanding. However, a few years later, graphic adventures would rise again from their graves, thanks in part to a team of designers who had formerly worked at LucasArts.

But more about that in the next installment of this post.