Night in the Woods tells the most vital story of any game in 2017. We’re only halfway through the year, but I doubt very much that it will be bested in this regard. Find out why below the fold, but beware of spoilers if you haven’t played it yet, and plan to. I will be discussing how this very important game’s themes resonate all the way to its ending.

Night in the Woods is the most 2010s game so far released in the 2010s. It pinpoints the fears and uncertainties of post-2008-recession America, in particular those portions of rural/small-town American that have been hit by the collapse of the industrial sector and the one-two punch of meth and opioids. You may call the denizens of these communities the rural precariat. You may call them the unnecessariat. Whatever you call them, they have not frequently been the subjects of videogames. Night in the Woods corrects this omission. Although I now live in a Midwestern city, I grew up in, and still have plenty of family ties to, a community much like the game’s Possum Springs. (This one, profiled just before the 2016 election, in fact.) I found Night in the Woods to be a revelation.

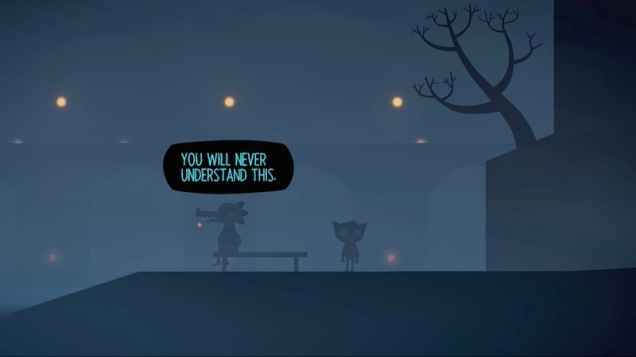

The game is striking in its precision: the shuttered shops, the service jobs taking over from industrial jobs, the emptying pews. It also casts a keen eye towards generational differences. This past decade of economic malaise has ground down on the Boomer generation and the Millennial generation in different ways, resulting in starkly divergent generational politics. And it is here, quite surprisingly, that the horror of Night in the Woods erupts.

I am just going to out and say it: It is inconceivable to me how this game, which was Kickstarted way back in March of 20-fucking-13, ended up being such a perfect allegory for the Trump/Brexit era.

Genre trouble

At one point, attempting to conjure a ghost while ambling around a graveyard, our player-character Mae (an anthropomorphic cat) asks her friend Bea (an anthropomorphic crocodile) to tell a scary story. Bea replies: “Things are like monumentally screwed right now. And no one in power gives a shit, or they’re actively making it worse, out of spite or profit.” Against Mae’s protestations, Bea continues spinning her terrifying yarn: “A regular stranger person outside your window. And he’s from the bank. He’s here to tell you they’re gonna take your house.” Mae charges Bea with being depressing and boring. Bea’s response? “The scariest stuff is like really really boring.”

From a certain angle, Night in the Woods proves Bea wrong. Bea doesn’t know she is in a horror game. She isn’t genre-savvy enough to foresee her story’s twists and turns. She doesn’t know that a few days later she’ll be staring into a hellmouth.

But, simultaneously, Night in the Woods also proves Bea right. Because deep down, what’s scary in Night of the Woods isn’t the ancient Lovecraftian deity dwelling unseen within the mines of Possum Springs. What’s scary is the loss of economic security, and the horrible lengths that some people will go to wrestle back even a modicum of self-respect.

This is all part of the generic dance of Night in the Woods. Mae is a college student who abruptly returns home. Initially this might be taken for a leave of absence, but as the game progresses it becomes increasingly evident that she means to drop out. Her reasons for doing this remain vague, as she is uncomfortable discussing them with friends or family. And so she loiters about, aimless, apathetic, in the recession-wracked community of Possum Springs, waiting for her friends to get off work so that she can hang out with them. Eventually, she witnesses a kidnapping. But this doesn’t happen for awhile. Night in the Woods aims for the quotidian slow burn of an Edward Yang film, where the unhurried rhythms of everyday life suddenly give way to shocking bursts of violence. On top of that, it adds a glaze of supernatural horror, without ever losing its grounding in careful observation of small-town life.

This sense of writhing generic unpredictability affects what you actually do in the game, as well. At some points, Night in the Woods is a rhythm game. At other times, it is an exploration-based 2D platformer. Predominantly, it is a visual novel: a fixed, linear narrative that asks players to click through mountains upon mountains of dialogue. And yet it is somehow also a Persona-style social simulator, asking you to decided which friends Mae should spend time with on her afternoons.

Not all of it works, not completely. The game’s pacing in its second act is severely off. The game stages a grisly, Blue Velvet-esque scene early on, clearly foreshadowing spooky and conspiratorial goings-on. From then on, players know that something is very well going to happen, but the game flat-footedly delays that something for hour upon hour. As a result, the slow pace of the game’s opening feels less like a simulation of Mae’s apathy and lethargy, and more like a storytelling problem. It doesn’t help that the early in-game days don’t quite communicate the desired feeling of emptiness: Mae is actually fairly busy, juggling numerous opportunities for socializing.

But I’ll forgive Night in the Woods its pacing, because of its sharp observations of the cultural realities of 2010s-era America, and small-town life in particular.

The residue of failed social mobility

Think pieces pitting “suffering rural white working-class Americans” against “city-dwelling cosmopolitan elites” are a dime a dozen. Within this crowded field, the standout entries pay close attention to the fact that this cultural divide is at least partially self-imposed. A fair number city-dwelling, college educate, socially progressive folks—myself included—grew up in small-town or rural America. We just moved to follow opportunity. Those still living there didn’t. They have remained in those hometowns, even as those hometowns have weathered unemployment, depopulation, and epidemics of addiction. The split between urban an rural, then, has become the split between opportunity-seekers and homebodies, between those who have adjusted to a 21st century skill set and those who are waiting for the old jobs to come back.

The question of how to negotiate the divide between those who leave small-town America and those who stay behind is a flummoxing one, and can produce strange political bedfellows. Opinion-peddlers on both the right and the left have suggested that rural America should be abandoned as a lost cause. “The truth about these dysfunctional, downscale communities,” wrote Kevin Williamson in a much-ballyhooed March 2016 National Review article, “is that they deserve to die.” Just yesterday, from the left, Thomas B. Edsel quoted James Stimson characterizing working-class Americans in rural communities as “the residue of failed social mobility, when most have been mobile”—that is, “those who are not willing to grab the ring,” preferring to instead “remain in the hometown and fear change and others.”

Of course, there are larger factors that can lead to a lack of geographical mobility, beyond personal moral failings. Geographic mobility in the US has been declining across the board in recent years (a trend accompanied by the hand-wringing of many a think-piece author). Running counter to Williamson or Stimson, other pundits have suggested that what is really needed to heal the country’s divisions is for those who can afford to be geographically mobile—i.e., the educated elite currently dwelling in cities—to spread themselves out into rural areas. J. D. Vance, one of the purest avatars of this idea, leans to the right. Again, though, the usual partisan divides have become scrambled around this issue, and Vance’s approach has found adherents across the political spectrum.

But what presumed solutions such as Vance’s miss is that small-town denizens aren’t just waiting with open arms for the empathy of the city-dwellers who left them. As Williamson and Stimson turn their backs on rural America, rural Americans also harbor resentment toward and about those who leave. This is something that Night in the Woods pinpoints quite deftly.

On the benign side, there is Bea. Bea spends much of the game resentful toward Mae, and with good reason. Mae stumbled into an opportunity that Bea wishes she could have had, and has been denied by the cruelty of circumstance. Mae has been granted a privilege simply by not having a parent die, a privilege which has left her with an utter obliviousness toward the reality of Bea’s situation. Mae had a chance to “get out,” and blew it for what seem like arbitrary and stupid reasons. Bea can’t fathom how she can’t see that.

That’s the benign side of things. Then there’s the cult of the hole. (From here on in, spoilers aplenty: Mae and her friends discover the existence of this cult late in the game.)

In the minds of the cult members of Possum Springs, young people leaving is a source of resentment, a symptom of a rotten state of affairs. One cult member offers the following description of the past decade of life in the town: “Jobs gone. Our kids were leaving. Government didn’t care, only wanted our votes. Just puttin in more regulations, sendin our jobs overseas, spendin our taxes on lazy people ‘n immigrants while we worked ourselves to death.” From this perspective, the young people who leave are an open sore, a constant reminder of a community’s steady decline. Offspring should be retained, and Possum Springs’ failure to do so is a testament to its decline.

The cult’s solution to this? Sacrifice. Not as in personal sacrifice—no, I’m talking human sacrifice. (Er, anthropomorphized animal sacrifice.) There is a hole deep in the mines of Possum Springs, a hole that houses some unseen eldritch deity. In an attempt to economically revitalize the town, the cult has been feeding “undesirables” into this hole. This includes homeless people. It also includes the town’s own youth, kids that they see as being on the wrong track, and lacking a strong work ethic—including one of Mae’s friends and former bandmates. Despite the continued decline of the region’s industries, the cult retains its absolute faith that irreversible economic trends can be turned around, and that Possum Springs can be made great again. “These mines are gonna be humming again someday. Old mills puffin’ smoke.”

There are echoes here of Moloch and Cronus, and of course the current political climate. “These mines are gonna be humming again someday” is the quintessential Trumpian promise. Its price? Pulling out of the Paris accords. The dismantling of public education. A rebuke of the future, in hopes of reinstating the past. A sacrifice of those needs most pressing to youth, as a way of restoring glory to their parents and grandparents.

World Death

We could stop here, drawing a parallel between the hopes of the cult and the hopes of Trump voters, and the game would be resonant enough to be noteworthy. But Night in the Woods offers a more far-reaching critique.

Because the cult isn’t some isolated aberration in Possum Springs. They are extreme, to be sure. But their game draws parallels between their efforts to appease a dark demigod and other, more quotidian attempts to win the appeal of unknowable forces.

For instance, Gary, one of the members of the town council, persists in his insistence that the town find ways to bend to the will of “the market.” “If we don’t start getting businesses in here, there ain’t gonna be a Possum Springs,” he says during a conversation on the local historical landmark status of a local statue, “So we gotta do whatever we can do to get the market to notice us.” Later, he shoots down an initiative on the part of the town’s pastor to set up a homeless shelter in town. Pastor Karen points out that the town has plenty of space, from abandoned buildings to empty pews: “The population drain in this region … you have to know this place’ll never be full again.” Gary won’t have any of this, though. Homeless sheltered won’t attract businesses—in fact, they will repel them. “Businesses mean jobs, and jobs mean people,” he insists. “We have to do what we can to get the attention of the market.”

Gary’s invocation of an anthropomorphized “market” that Possum Springs needs to serve and attract—is this really all that different from the deities the cult worships? Both are intangible and unknowable. Both promise rewards if you can do their bidding: mines humming again, old mills puffing smoke, new businesses bringing new jobs. And both require the sacrifice of those who are homeless, downtrodden, and down on their luck.

And these sort of abstract entities are precisely what one grasps out to when one’s world is dying. The end of the world is a consistent theme as the miners explain their position. Not “the end of the world” as a global apocalypse, but the end of a specific world, of the scaffolding of meaning that one has used to make sense of one’s actions and their social status. “You kids don’t understand that,” the cult’s primary interlocutor intones to Mae:

We lost what our world was built around. Used to be you provided for a family, bought a house. Now you’re stockin’ shelves at a grocery store. Kids leavin’ more than they’re stayin’ … no opportunity here. Old people dyin’, houses left empty. You ever see that? A home become a tumbled-in pile of wood and plaster? A job become a burned out brick box or hole in the ground?

There is a lament here, not just for buildings ground down by collapse and decay, but for institutions stripped of significance. I’m reminded of the moments when Heidegger describes the alien quality that takes over when the “equipment” of our everyday lives is “deprived of its worldhood,” becoming “present-at-hand and no more.”[i] I am reminded, too, of Jonathan Lear’s Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation, where he ponders what it means to survive the collapse of one’s society, and with it all markers of meaning, all social contracts, and all sense of what it is to act as a moral agent. (This stripping of significance is most pronounced in the profound psychotic break that Mae eventually admits to having had, in which she slipped out of realm of meaning, and the people and things around her became “just shapes.”)

It is times like these that one might find oneself reaching out to the ineffable, grasping at whatever straws faith can offer. The cultists have their faith in the eldritch horror intoning to them from the depths of the hellmouth. Gary has his faith in the invisible hand of “the market.” Both make promises. Both are equally unknowable and impersonal in their strange, inhuman logic.

Night in the Woods is not optimistic about the possibility that Possum Springs could ever recover, despite the best combined efforts of the cult and the town council. I did, though, find the game to be optimistic in its own askew way.

This mainly comes down to the line that opens the cultist’s speech: “You kids don’t understand that.” Indeed, they don’t. The millennial protagonists of Night in the Woods don’t understand what it’s like to have the job that provides for your family to be taken away, to have your house foreclosed upon. They don’t understand it because they don’t expect to be able to provide for families, or buy a house. Those dreams are long gone, and they are not the ones animating this generation. Moving out of town and renting an apartment in a terrible neighborhood of the economically-functional Bright Harbor seems like a more attainable dream.

One could portray this as a tragedy: do the usual hand-wringing about how millennials’ failure to pursue homeownership and get married is a sign of the decline of the American Dream. In Night in the Woods, though, it’s more of a sign that the kids are alright.

Not having these expectations in place means that they can’t feel the sense of entitlement and betrayal that the cultists do when things don’t turn out the way they were promised. Much like Joel’s character arc in The Last of Us (Naughty Dog, 2013), the Possum Springs cultists are driven to do terrible things as a perverse way of emotionally coping with loss. Night in the Woods holds out the hope that a generation who might not have experienced that same loss—simply because it preceded them, and formed the baseline normalcy of their life—might be open to different, less monstrous ways forward.

After all, none of Mae’s friends sit around worrying about “the market” and how to bend to its will. Gregg is an anarchist. Bea is the leader of the local Young Socialists chapter. In place of the cult’s mourning of an irretrievable past, the youth of Possum Springs seem willing to dream up more radical futures.

Final Thoughts

Night in the Woods is not an “empathy game.” It doesn’t labor under the assumption that we can only understand the problems of others if those problems are elaborately simulated, allowing to digitally walk in another’s shoes. Instead, it simply pursues the age-old conviction that stories are important, and that well-crafted works of art can get us to care about others and their lives.

Night of the Woods has the most diverse and fully-realized cast of characters I have ever seen in a game, and their interactions are delicately realized.[ii] The game displays so much warmth and humanity towards these anthropomorphic critters. This extends to very subtle aspects of its animation, which was a constant marvel. Just look at how the eyes of the homeless man Bruce shift to avoid Mae’s as he talks about his daughter below.

Or the dynamic animation of Mae’s eyes in the clip below, which peer into the distance or drift back up at her mom, depending on where I last pointed the analog stick:

You don’t need to simulate someone’s daily life to create “empathy.” If you care enough for your characters to build a well-realized work of art around them, than your audience will, too. Games are more than the sum of their mechanics.

I could continue offering words of appreciation for this game, but I need to wrap this post up at some point. I will close with with lines from a poem, offered by Mae’s friend Selmers. Selmers is recovering from a painkiller addiction, and writes little poems, which she recites to Mae every day if Mae expresses interest. Selmer’s poems are usually short and rather silly, qualities which Mae appreciates. But when Mae shows up to the Possum Springs Poetry society, expecting more of the same goofy rhymes, she is instead bears witness to this:

I read on the Internet baby face boy billionaire

Phone app sold made more money in one day than my family over 100 generations

More than my whole world ever has

World where house-buying jobs became rent-paying job became living with family jobs

Boy billionaires

Money is access access to politicians waiting for us to die lead in our water alcohol and painkillers

Replace my job with an app replace my dreams of a house and a yard

With a couch in the basement

“The future is yours!”

Forced 24-7 entrepreneurs.

The eloquence, the holy rage: it takes us, and Mae, by utter surprise. We have underestimated Selmers. And we shouldn’t have. This is part of Night in the Woods‘ compassion toward its characters. These characters aren’t mere levers for empathy. They are complex creations that demand our respect. They can challenge us, and our expectations. They can make us think.

Night in the Woods, too, is a complex creation that demands our respect. It can challenge us. It can make us think. It certainly made me think, and I hope it does the same for you.

[i]. Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. 1927. Trans. John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. New York: Harper Collins, 1962. Pg 147.

[ii]. Again, I must acknowledge that the game is not perfect. My second constructive criticism, aside from the failures of the game’s pacing, would be directed to its humor. Every character tells the exact same sorts of jokes. No matter how clearly-realized these characters are in their other particulars, they all channel the same reservoir of dry, sarcastic wit. To be clear, I very much liked the humor of the game’s writing. But it was nevertheless a little jarring to hear the same dry commentary coming from Mae’s frustrated and resentful 20-something friend Bea, and her kind, devout mother.