It was a dark (and possibly stormy) night in the year of our Lord 1848.

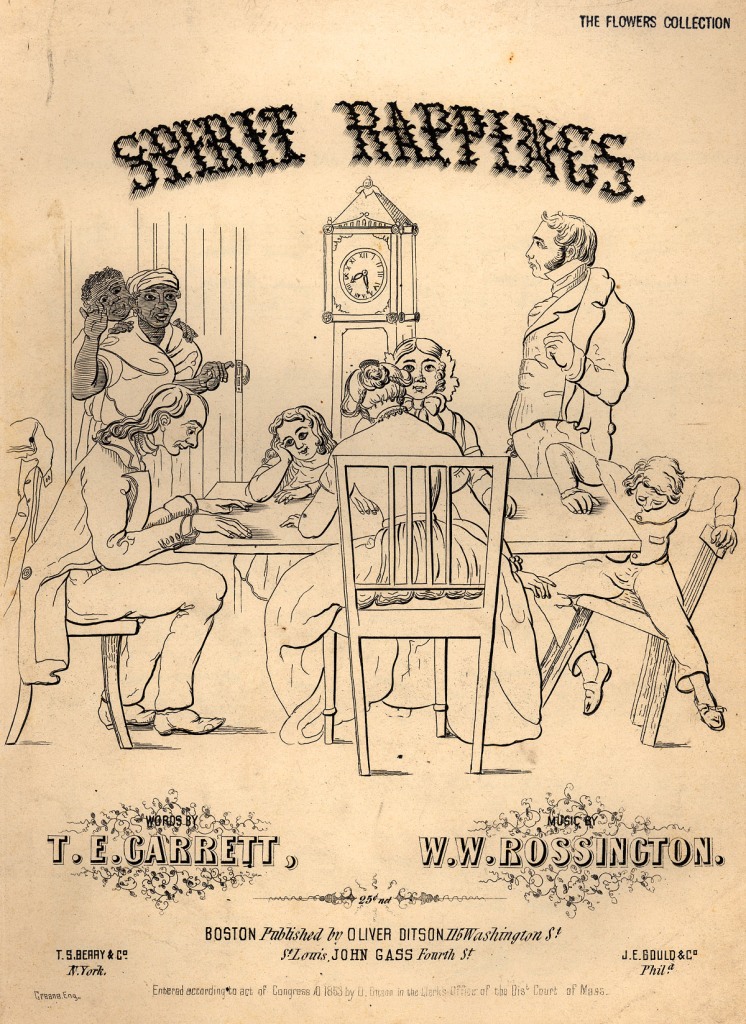

The Fox family of Hydesville, New York, (mother, father, and two girls) prepared to go to bed as usual. And as had become usual for them, the darkness was punctuated by mysterious rapping noises. They came from nowhere. Nothing visible was causing them. They had searched all over by candlelight and found no animals, no tree branches, no anything to cause the rapping.

But that night was different. For Kate and Maggie (approximately 12 and 15 years old) decided to try making a similar noise by snapping their fingers. And no matter how many times they snapped the mysterious rapping repeated the same number of raps. The noises were not random. Terrified, the girls called their mother Margaret to hear.

“Count to 10,” Margaret commanded. <ten raps>

“How old are my daughters?” she asked, and the rapping gave the answer.

Margaret asked: if it was a human being, make a noise. <silence>

If it was a spirit, to make two noises. <two raps>

Was it an injured spirit? <two raps>

Injured in this house? <two raps>

Possibly buried under this house? <two raps>

Sick with fear, Margaret asked: if she called her neighbors for support, would the spirit continue to rap? <two raps>

A reluctant Mr. John Fox was dispatched to tell the neighbors that his house was haunted. They came to see, and over the next few hours, the story was teased out of the ghost. It was the ghost of a peddler, murdered for his $500 in his cash box by a previous resident of the house, John Bell. The peddler’s ghost knew intimate details about the entire neighborhood: how many children each family had, how many had died in each family, etc. The ghost could also direct them to exactly where in the cellar they could dig to find his grisly remains.

Not until midnight did the Fox women stagger into bed, and those beds were at the neighbor’s houses.

The next night, the sounds began again, to the amazement of several hundred curious visitors, all of whom heard the ghost. By then, the questions had branched out into broader significance.

Was Universalism true? <silence>

Was Methodism true? <two raps> (That was a relief. The Fox family was Methodist.)

Was there a heaven? <many enthusiastic raps>

Was the neighbor’s recently deceased child Mary in that heaven? <two raps>

Are the spirits of our beloved dead around us? <two raps>

The assembled company felt comforted and known.

Such was the testimony given only a week and a half later by Mrs. Margaret Fox, Mr. John Fox, and multiple other witnesses, all published in a tract by one E.E. Lewis, and impressively titled A Report of the Mysterious Noises Heard in the House of Mr. John D. Fox, in Hydesville, Arcadia, Wayne County, Authenticated by the Certificates, and Confirmed by the Statements of the Citizens of That Place and Vicinity. How’s that for a snappy title?

Lewis exhaustively covered the ground, trying to approach this haunted house with journalistic integrity. He interviewed dozens of people, and yet it never occurred to him to interview the young girls of the family. He only interviewed the adults.

His account did include a signed statement from forty people saying John Bell was a man of good character, and he would never have murdered anyone. But also Bell’s former servant came forward to say, a peddler had called there a few years ago and she had been sent away for a time, and when she came back, the peddler wasn’t there anymore! Very suspicious. . .

Excavations in the cellar hit ground water before they hit a skeleton, but that wasn’t proof. They hadn’t excavated the whole thing.

By this point life was totally disrupted for the Fox family. Margaret was refusing to live in the house anymore, and strangers were trampling their fields and peeping in the windows, either because they hoped to hear a ghost or because they hoped to uncover a fraud.

A Multiplicity of Ghosts

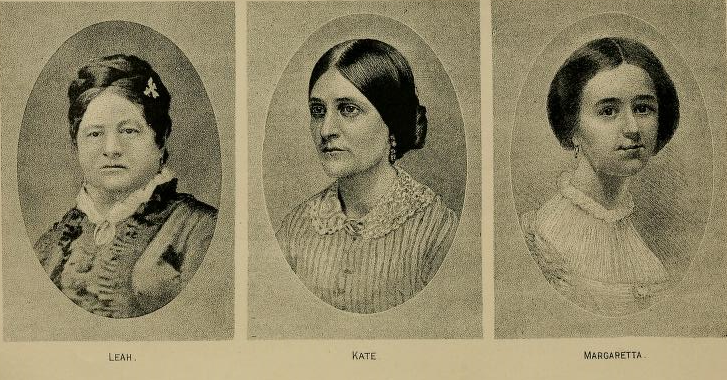

The Fox’s had another daughter, Leah, who was much older than Maggie and Kate. She had married and had a child, but her husband had abandoned them. Leah was living in nearby Rochester, supporting herself by teaching piano lessons when she learned of her family’s new notoriety. She hurried home to help and brought Maggie back to Rochester with her.

Only to find that the spirits followed them to Rochester and they stayed in Hydesville. They were spreading.

What’s more, they had gotten more disturbing. No longer just rapping, the spirits now opened and shut windows, they slammed doors, they danced with clogs, they passed cold hands over the family’s faces. Kate fell into a trance, and though seemed to be dead, she answered questions by pressing hands.

In Rochester, Leah began holding small gatherings in her home with Maggie as a medium. Friends and neighbors would come and ask questions of the spirits, who would usually (but not always) answer with rapping or table tiltings. Leah would play religious music on the piano to add to the mood.

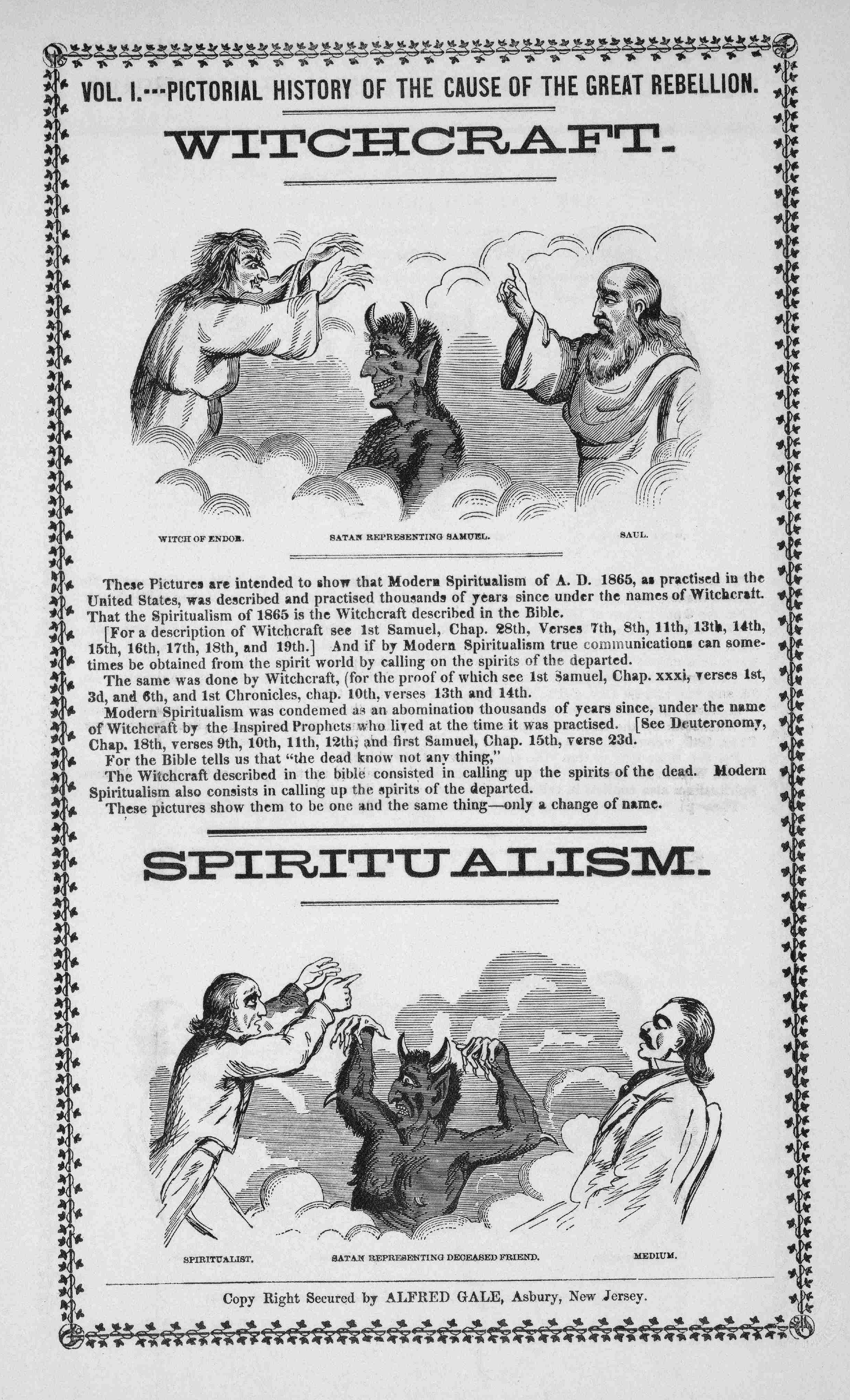

Ghosts were nothing new in history, of course, but these meetings held by the Fox sisters were the origin of Victorian séances, the beginning of what would eventually be called Spiritualism and take the world by storm. Before this point, ghosts were a negative thing. If you saw one, you probably called for the local priest to perform an exorcism. Hamlet’s father and Scrooge’s Jacob Marley were helpful—sort of—but also terrifying and devastating. You certainly didn’t invite ghosts to come visit you. But the Fox sisters did. Within a just few years, Mary Todd Lincoln would hold séances in the White House, and Queen Victoria would hold them in Buckingham Palace, and as I described in episode 10.11, artist Hilma af Klint would hold them in Sweden. It all began here with the Fox sisters.

By the end of the summer of 1848, communication with the spirits had been refined so that they could use the alphabet to rap more than just yes or no.

Also the digging in the cellar had yielded hair, bone fragments, and pots like a peddler would carry. Therefore, it was all true.

The Business Affairs of Ghosts

By the fall of 1849, the spirits wanted wider publicity. They demanded a public revelation, or they would leave for good. They went about it very business-like. They took stock of the current circle of friends and believers and informed one that he would be in charge of business affairs. Another that he would write and deliver lectures on spirit communication. They demanded practice sessions to determine how large a room still allowed the raps to be heard.

On November 14, 1849, Rochester’s largest theater admitted 400 patrons at 25 cents per ticket to see and hear Leah and Maggie commune with spirits from the other side. Which they did with remarkable success. A committee of five respectable citizens investigated and could discover no fraud.

The next night another public séance and another committee found the same thing. The third night another public séance to an increasingly riled crowd who insisted on still a third committee, this time with a subcommittee of ladies who took Maggie and Leah behind closed doors and stripped them to look for concealed devices while the titillated crowd of gentleman waited and imagined the scene.

By the fourth night the ruckus was so wild that the Fox sisters needed police escort to get home, and Maggie was convinced she would be murdered. She was not being irrational. Mob violence was a real and mostly unpunished crime in mid-19th century America, perpetrated against those who violated social norms, and the Fox sisters had certainly done that. Regardless of whether they were or were not in communication with the dead, they had indisputably thrust themselves into the public eye—not at all ladylike—and they had allowed themselves to be disrobed and reported on to men at large, which was practically the behavior of a prostitute.

They had officially achieved infamy, and their names were in publications across the country. The Fox sisters retreated back into private séances, but they did charge for them. And why not? They needed support. There was no man in their lives pulling in a steady income. John Fox was an alcoholic who had distanced himself from all this spirit mumbo jumbo. Bowman Fish, Leah’s husband, was totally absentee. She sometimes called herself a widow, which was not true, but life was hard for an abandoned woman. It’s not like there were a lot of social programs or job opportunities.

It is true that the spirits were sometimes a surprise to the paying customers. It turns out that spirits make spelling mistakes and they get offended. They sometimes refuse to answer. Or squabble amongst themselves. Or they ask for another day to consider before responding. The skeptics had uncharitable explanations for all of those facts, but as the rapping answers proved intimate knowledge of the listeners and dispensed solid predictions, not to mention the furniture floated, and drawers opened and shut, there were many, like a certain Charles Hammond, who felt, “That any of the company could have performed these things, under the circumstances in which we were situated would require a greater stretch of credulity on my part, than it would to believe it was the work of spirits” (quoted in Weisberg, 100).

To be honest, there were many things happening in the world that strained credulity. Physical distance had been conquered first by the railroad and more recently by the telegraph. The skies had been conquered by hot air balloons. The oceans were more or less mapped. Scientists were performing miracles with electricity and magnetism. Tasks that had once consumed men and women for large segments of their lives were now performed by machines like the power loom and the cotton gin. Time itself was in some senses conquered by the invention of photography, which allowed you to stop time, by capturing a moment. And on the social front, there were blacks arguing for their freedom, and women arguing for their freedom, and people under oppressive regimes around the world fighting for their freedom. Barriers that had once been accepted as inevitable (not even worth questioning) were crashing down. Why should the barrier of death be any different?

In April of 1850, Margaret and her daughters Maggie and Kate went on their first public tour. They appeared in Albany, Troy, and New York City. All kinds of people crowded in to see and pay and publicize for them. Among these people were Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune, a famous abolitionist. And James Fenimore Cooper, the author of Last of the Mohicans. And Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale, who you might know from The Greatest Showman.

The girls were sometimes working together and sometimes operating apart. But they always had flocks of the faithful. They also had flocks of the critical. Scholars, ministers, and jealous wives, all had different motivations for finding fault with them on practically everything. Witches were no longer burned at the stake, but there were people who found that a tempting solution.

Many committees investigated them, and some claimed to have found the means of the deception, but whatever they said, it never made a whole lot of difference. In one test where the girls were tied up, the rapping did stop, but Leah said that was because the spirits were offended by the rough treatment. Leah also gave free sances for two weeks following as proof of her sincerity. Of course, by now, she could well afford to do so.

The touring went on throughout the northern United States. Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave, was one of their guests, and Maggie thought him very good looking.

A Love Affair with a Medium

Years passed, and the famous girls were rapidly becoming famous women. Charming, well-dressed women. Maggie fell in love with Elisha K Kane, a well-known Arctic explorer. He loved her too, only there was a snag. His prominent, well-respected family could never have accept a woman from a family with no social connections, who was constantly in the public eye, accused of witchcraft and fraud, and basically are the shades of Pemberley to be thus polluted? No, they shall not be!

Kane himself had similar thoughts. He ardently admired and loved Maggie. But in declaring himself thus he was fully aware that he would be going expressly against the wishes of his family, his friends, and he hardly need add, his own better judgment. The relative situation of their families was such that any alliance between them must be regarded as a highly reprehensible connection. Indeed as a rational man, Kane could not but regard it as such himself.

His situation, as you may have picked up on, was exactly like that of Mr. Darcy, but I am sorry to say that Kane did not take the Mr. Darcy route for dealing with this. Instead he proposed, changed his mind, made up again, insisted their relationship be kept secret, begged her to give up spiritualism, paid for her to go to school where she could learn to be the “right” kind of woman, proposed again, changed his mind again. And on and on. Basically, your bog-standard emotionally manipulative relationship, where he definitely wanted her, but he wanted her different because she was actually not good enough for him.

After damaging both Maggie’s sense of self and her relationship with Leah, who was urging her to chuck the loser once and for all, then he up and died, leaving Maggie in a real psychological mess, for maybe she should have given up spiritualism, maybe she was all wrong for him, and basically it was all her fault. Kane had married her, in secret, and she was going to be faithful to his memory for the rest of her life. Now she gave up séances because he had wanted her to. She converted to Catholicism because she said he had wanted her to (which is odd because he wasn’t Catholic). She changed her last name to Fox Kane, as befits a married woman.

The Kane family was unimpressed. They said, no, there wasn’t any secret marriage. Our darling boy would never have done that. And if you’re making this up to get a widow’s settlement, think again, but we do want all the letters he wrote you to make sure you never publish them. The lawsuits went on for years, and Maggie had neither a settlement, nor income from séances since she had given those up. Like her father before her, she settled into poverty and alcohol.

Kate, in contrast, was still going strong. She had no serious suitors and the onset of the Civil War meant there were millions upon millions of grieving people who desperately wanted to contact their loved ones on the other side. One of her customers was none other than Harriet Beecher Stowe. And yet, Kate too was not immune to the pull of alcohol, particularly after her parent’s death.

In 1871, the spirits advised that she should go abroad and get a fresh start, and their advice was good. In London, she met a good man, and they were married in 1872, in a wedding punctuated by many raps from jubilant spirits. Kate’s talents were as much in demand in England as they had been in the US, for spiritualism had spread. She would eventually even travel to Russia to give séances for the royal Romanov family.

A Public Confession

By the 1880s serious organizations were investigating spiritual phenomenon on both sides of the Atlantic. So it was a blow when on October 21, 1888, at a well-publicized event in New York, Maggie went onstage to say it had all been a pack of lies. It had been four decades since that dark night in Hydesville. The Fox sisters were world famous. They had brought comfort, delight, and awe to thousands. They had suffered accusations from all sides, some of them violent. And now Maggie patiently and publicly explained how it had been done. She and Kate made the raps by cracking their toes.

It had started as a joke. Maggie said. They were so young, and their mother so gullible. It was the greedy and ambitious Leah who had manipulated them (sweet and innocent as they were). It was she who had urged them to move from private pranksters to master frauds on the world stage. Basically, it was all Leah’s fault. And now Leah was safely married again to a rich man and had nothing to worry about. Well, Maggie had done with so much deception in her life, and in making this pronouncement, she felt sure that her own dear departed husband was looking down on her from heaven and blessing her.

The press reported it as the death blow for spiritualism.

But it wasn’t.

Those who did not want to believe in Spiritualism already didn’t believe, so Maggie’s confession was gratifying, but not life changing.

Those who did want to believe found plenty of ways to explain her defection. She was clearly unwell, suffering from long years of alcohol abuse, and maybe more than that. She deserved compassion, but not trust in her current statements.

Or another theory: she had switched sides for financial reasons. Given her famous history, she could probably now make more money denouncing spiritualism than in propounding it. Books and lecture tours could both make a fortune on such an explosive topic.

Or yet another theory: she was simply irrelevant. The fact that she was a fake did not mean that all mediums were.

A Public Retraction

And then a year later, Maggie recanted her confession. Why? Because the spirits told her to. They were rapping so loudly, they were waking her neighbors.

And so all three sisters continued as mediums until they died, all of them in the 1890s. Mediums received messages from their spirits at least into the mid-20th century and maybe they still do.

So what do you make of the Fox sisters’ story? There is obviously an argument that they were liars and deceivers from beginning to end, preying on the hopes and fears and ignorance around them. All of the phenomena their guests described can be produced by competent stage magicians.

But there are also more complex explanations. They could have engineered every one of the conjuring tricks and yet believed they were doing it at the behest of other-worldly influences. Both Maggie and Kate suffered from migraines, which can induce premonitions, seeing auras or bright lights, tingling, sensitivity to sound—basically many of the phenomena they described as spirits.

Whatever the health problems, the 19th century solutions, usually involved a combination of alcohol, morphine, and opium, all readily available, and all capable of inducing the same kind of symptoms. It is also possible that many of their guests were seeing and hearing more than was really there because they too were under the influence.

There is even a psychoanalytic theory that claims Maggie and Kate were doing this unconsciously, in reaction to abuse from their childhoods.

Or maybe they were conscious deceivers, but not so much to be predatory, as to be entrepreneurial. They were feminists looking for a voice, and they succeeded wildly well in a world that offered few opportunities for unattached women.

Or maybe it was just ghosts after all.

Selected Sources

Abbott, Karen. “The Fox Sisters and the Rap on Spiritualism.” Smithsonian, Smithsonian.com, 30 Oct. 2012, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-fox-sisters-and-the-rap-on-spiritualism-99663697/.

Midorikawa, Emily. “The Fox Sisters: Spiritual Awakening or Death-Blow to Spiritualism?” University of London, 29 Oct. 2018, http://www.london.ac.uk/senate-house-library/blog/fox-sisters-spiritual-awakening-or-death-blow-spiritualism.

Weisberg, Barbara. Talking to the Dead : Kate and Maggie Fox and the Rise of Spiritualism. San Francisco, Harpers, 2005.

White, Edward. “In the Joints of Their Toes.” The Paris Review, 4 Nov. 2016, http://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2016/11/04/in-the-joints-of-their-toes/.