Adelita is a nickname given to women soldiers or soldaderas who fought along side men in battle during Mexico’s Revolutionary War (1910-1920). Many of us depict these brave women when we perform the dances of La Revolución. I first learned La Revolución as a dancer with Roy Lozano’s Ballet Folklórico de Tejas in the 1990s. Roy Lozano, my teacher, passed on the choreographies that he learned from performing with the Ballet Folklórico de México de Amalia Hernández in the late 1970s. Following this dance tradition, I have taught these dances to my own company which have been in our own repertoire since 2003. Yet, I feel that our folklórico practice encourages a romanticized view of the las adelitas. Quite recently, I began to deep deeper into historical accounts and realized that there was so much that I didn’t know.

- 1. The word soldaderas refers to women who followed men in camp and those who fought in battles. During Mexico’s Revolutionary War, soldiers paid women to work on their behalf as servants. These women purchased supplies, cleaned clothes, cooked, cared for the sick, buried the dead, and some were prostitutes. Many women were expected to follow their husbands, fathers, brothers, lovers, etc. into the military. Yet, others fought in battle as soldiers, generals and colonels. They lead militias of men and women troops to fight during the Revolution (Salas 1990, xii, 44; Monsiváis 2006, 5).

- 2. Not all women willingly followed men in battle. Some were abducted and raped. There are stories of young girls been taken from their homes and forced to follow the troops while their mothers cried at home. Newspaper accounts tell of women kidnapped on trains and even one reports that forty women, almost the entire female population from the village of Jojutla, were abducted by Zapatistas. Nuns were taken from their convent and forced to accompany the Carrancistas. After the war, many of these nuns were pregnant or had children of their own. Parents fought back by hiding their children in the fields, posting look outs for revolutionaries, disguising their daughters etc. (Salas 1990, 40-42).

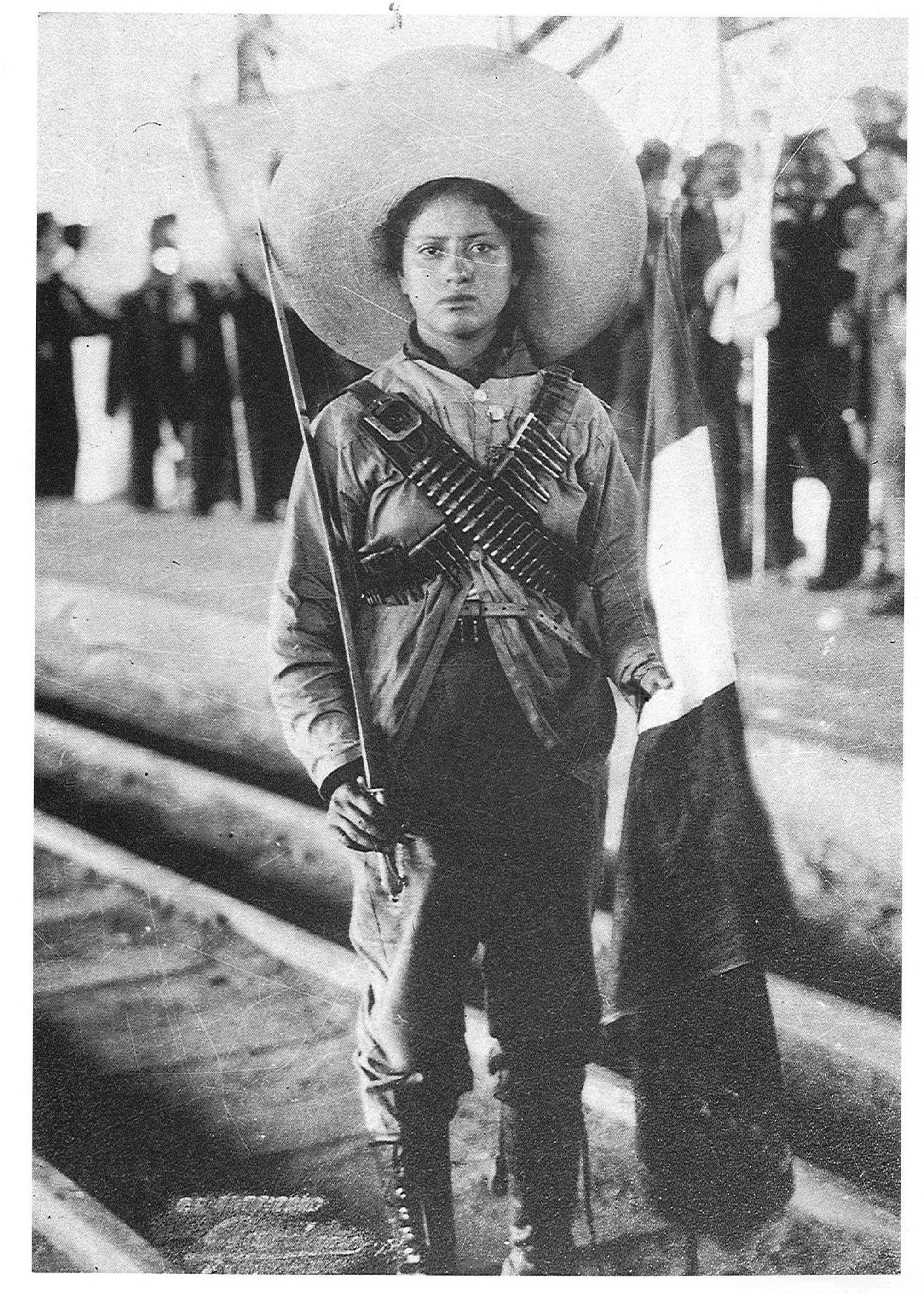

- 3. Women were so very brave. They lead regiments of men in battle as colonels and generals. They also led regiments comprised entirely of women in battle. Women were sent on secret spy missions, brought ammunition to men while dodging bullets during the line of fire, and some were so courageous that they were feared and respected by men (Salas 1990, 41-43).

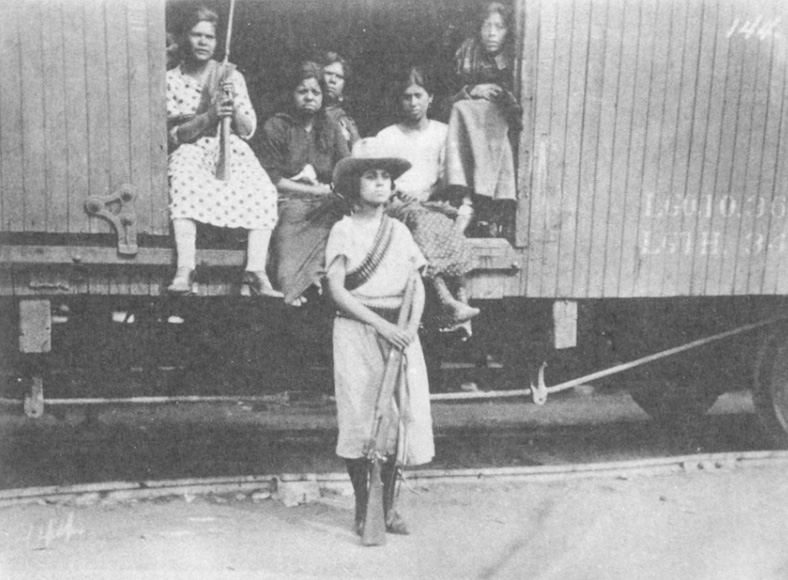

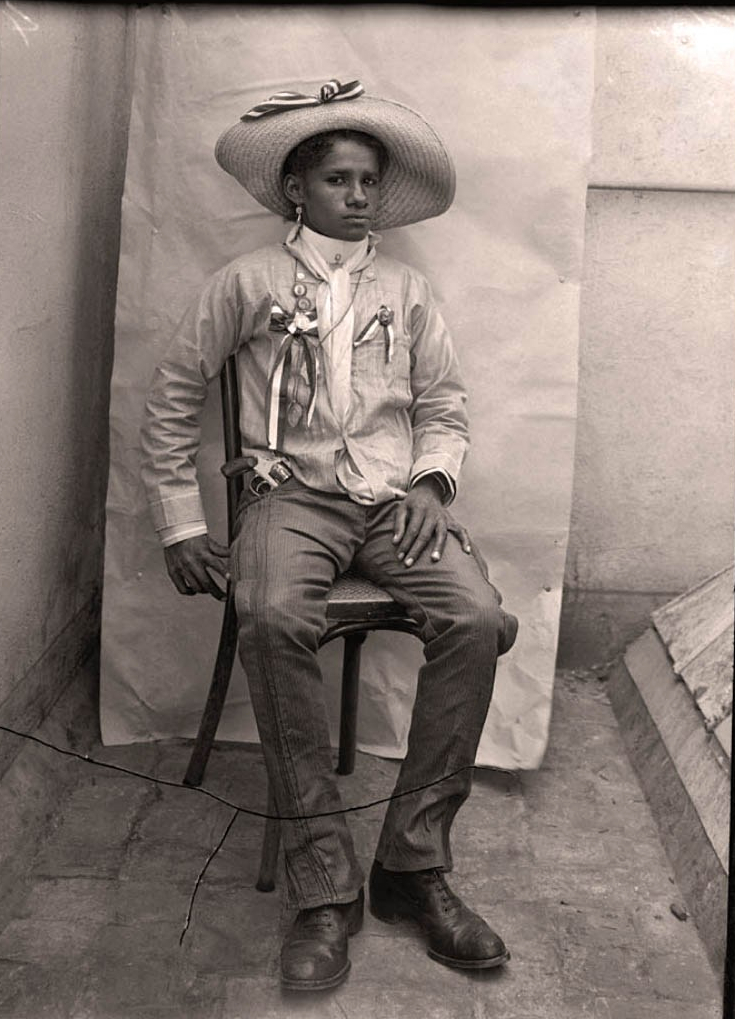

- 4. As we dance Las Adelitas we wear cartridge belts around our torso, carry rifles and use a serious expression to portray these tough, courageous women. We wear skirts and blouses typical of the time period. Yet, some soldaderas dressed as men. They wore pants, shirts, or even dressed in men’s military uniforms. See pictures below.

- 5. After the Mexican Revolutionary War, women’s military contributions were devalued. Women were not called colonels or soldiers but were listed under the general term of soldaderas. The military classified soldaderas as wives. Very few women veterans received military pensions. Most did not. Women who did receive pensions could not re-marry nor officially participate in the military (Arce 2017, 65, 82). In addition, after the Revolution, images of the soldaderas were romanticized in literature, film, art, and song. Soldaderas were not depicted as diverse, independent women many of which fought in battle but instead they were cast along four main stereotypes. Soldaderas were characterized as either self-sacrificing, sexually carefree, sweethearts, or soldiers (Salas 1990, 69, 82).

My Thoughts

I have danced and taught the choreographies that represent La Revolución for years.Yet, I believe that a close study of history alongside our folklórico practice really allowed me the ability to fully appreciate the individual spirit of these brave and courageous women.

Written by Gabriela Mendoza-Garcia Ph.D.

Works Cited

Arce, Christine.2017. México’s Nobodies: The CulturalLegacy of the Soldadera and Afro-Mexican Woman. Albany: State University ofNew York.

Monsiváis, Carlos.2006. “Foreword.” In Sex in theRevolution: Gender, Politics, and Power in Modern Mexico, ed. JocelynOlcott, Mary Kay Vaughn, and Gabriela Cano. 1-20. Durham: Duke University Press.

Salas, Elizabeth. 1990. Soldaderas in the Mexican Revolution: Myth and History. Austin: The University of Texas Press.

FurtherReading

Craske, Nikki. “Ambiguities and Ambivalences in Making the Nation: Women and Politics in 20th Century Mexico.” Feminist Review.79 (2005) 116-133.

Olcott, Jocelyn, Mary Kay Vaughn, and Gabriela Cano. 2006. Sex and the Revolution: Gender, Politics, and Power in Modern Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press.

Poniatowska,Elena, 2016. Hasta no verte Jesús mío.Madrid: Alianza Literaria.

Schaefer, Claudia. 1992. Textured Lives: Women, Art, and Representation in Modern Mexico. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

Turner, Frederick C. 1967. “Los Efectos de la Participación Femenina en la Revolución de 1910.” Historia Mexicana. 16 no. 4 (April-June): 603-620.

All photos are in the public domain.

Copyright, 1/6/2019, Mendoza-Garcia

Gabriela Mendoza-García Ph.D. is an Artist and Scholar. She has her own dance school and company called the Gabriela Mendoza-García Ballet Folklórico in Laredo, Texas. Dr. Mendoza-Garcia founded this group in 2013 and teaches children and adults of all ages. Her company consists of seasoned folklórico dancers with years of experience performing this art form. She teaches traditional Mexican folklórico dance pieces, as well as, works that are inspired by her scholarly research. Her scholarship includes: Dancing throughout Mexican History (1325-1910), History & Folklore booklet with an accompanying documentary sponsored by the Webb County Heritage Foundation, The Jarabe Tapatío: Imagining Race, Nation, Class and Gender in 1920s Mexico published by Oxford University Press, an on-line blog, writings for Asociación Nacional de Grupos Folklóricos, and others.

Pingback: Summer Reading for Folkloristas of all Ages | Gabriela Mendoza-Garcia Ballet Folklorico

Pingback: Cupid’s Arrow: Folklórico Choreographies to Love | Gabriela Mendoza-Garcia Ballet Folklorico

Pingback: Mexican Traditional Coffee Is A Unique Brew - ViralTab

Pingback: Mexican Traditional Coffee Is A Unique Brew – The Wilmington Journal

Pingback: Mexican Traditional Coffee Is A Unique Brew - Metropoli Hoy

Pingback: Las Soldaderas, the Women Who Fought in the Mexican Revolution | History Hustle

Pingback: Far Cry 6 Good Where it Counts – 4 Things it Gets Right