Overview

The anatomy of the regions and planes of the abdomen is composed of many layers with varying blood supply and innervation. The abdomen has been bisected, trisected, and even divided into as many as 9 separate regions. The layers of the abdominal wall consist of the skin, superficial fascia, and muscles.

Abdominal planes

The anatomic planes of the abdominal wall are made up of multiple muscular and fascial layers that interdigitate and unite to form a sturdy, protective musculofascial layer that protects the visceral organs and provides strength and stability to the body's trunk. This anatomy varies with respect to the different topographic regions of the abdomen; thus, a firm understanding of these layers, their blood supply, and their innervation is essential to surgical management of the abdomen.

The abdominal cavity is the largest hollow space in the body. It is bound cranially by the xiphoid process of the sternum and the costal cartilages of ribs 7-10; caudally, by the anterior ilium and the pubic bone of the pelvis; anteriorly, by the abdominal wall musculature; and posteriorly, by the L1-L5 vertebrae.

Abdominal regions

The abdominal wall has few anatomic landmarks. The flat abdominal plane is broken up only by the costal margins, anterior superior iliac spines, and the umbilicus. Thus, many attempts have been made over the years to describe what surface anatomy cannot.

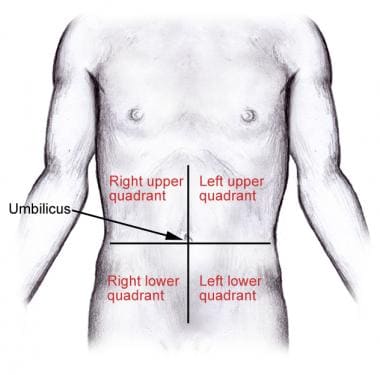

The most common and widely accepted system for identification of the various regions of the abdomen is the simple division of the abdomen into 4 quadrants by a vertical and horizontal line bisecting the umbilicus and forming the right and left upper and lower quadrants (see the image below). [1]

Abdominal Skin

Langer lines

As elsewhere on the human body, the abdominal skin is transgressed by Langer lines, also called cleavage lines. This is a term used to define the direction within the skin along which the skin has the least flexibility and corresponds to the alignment of the collagen fibers within the dermis. Across the superior half of the anterior abdominal skin, these lines are oriented in a transverse direction. Toward the inferior half of the abdominal skin, these lines begin to assume a slightly more oblique course in an inferior medial direction toward the groin, paralleling the inguinal crease.

Innervation

The abdominal skin is innervated in a segmental pattern by the anterior rami of the T7-L1 thoracoabdominal nerves. T7-T9 thoracoabdominal nerves innervate the skin above the umbilicus; T10 thoracoabdominal nerves innervates the skin around the umbilicus; and T11 thoracoabdominal nerves plus cutaneous branches of the subcostal (T12), iliohypogastric, and ilioinguinal (L1) nerves supply the skin inferior to the umbilicus. [1]

Superficial Fascia

The superficial fascia of the abdominal wall is the next layer encountered just deep to the skin. It consists of connective tissue that contains a variable amount of fat. This layer can vary in thickness from less than 1 cm to greater than 15 cm, depending on a person's body habitus.

Camper and Scarpa fasciae

Superior to the umbilicus, the superficial fascia consists of a single layer. Inferior to the umbilicus, it splits into 2 layers. The more superficial and fatty layer is the Camper fascia. The deeper, more fibrous layer is the Scarpa fascia. The Scarpa fascia contains very little fat and is continuous with both the superficial fascia of the thigh known as the fascia lata and the superficial fascia of the perineum known as the Colles fascia.

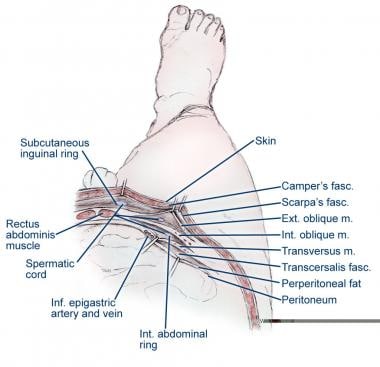

The fasciae are displayed in the image below.

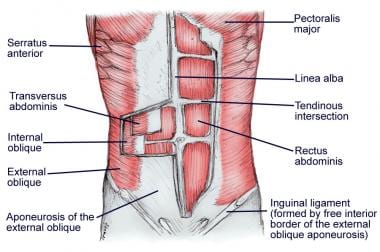

Muscles of the Abdominal Wall

The abdominal wall is composed of 5 paired muscles: 2 vertical muscles (the rectus abdominis and the pyramidalis) and 3 layered, flat muscles (the external abdominal oblique, the internal abdominal oblique, and the transversus abdominis muscles). These muscles and their fascial attachments interdigitate and unite to form a sturdy, protective musculofascial layer that gives strength and support to the anterolateral abdominal wall (see the images below).

Muscular layers of the abdomen. Ext. = exterior; fasc. = fascia; Inf. = inferior; Int. = interior; m. = muscle.

Muscular layers of the abdomen. Ext. = exterior; fasc. = fascia; Inf. = inferior; Int. = interior; m. = muscle.

External abdominal oblique muscle

The external abdominal oblique muscle is the largest and most superficial of the 3 paired, flat abdominal muscles. It arises from the lower 8 ribs and interdigitations of the serratus anterior muscle. As the external abdominal oblique courses in an inferior medial direction, its muscle fibers change from thick muscle to a fibrous aponeurosis that inserts medially in the linea alba. Inferiorly, the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis folds back on itself to form the inguinal ligament between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle before inserting onto the pubic tubercle and the anterior half of the iliac crest. Just medial to its insertion on the pubic tubercle, the aponeurosis divides and forms the superficial (or external) inguinal ring. [2]

The external abdominal oblique is innervated in a segmental pattern by the anterior rami of the inferior 6 thoracoabdominal nerves (T7-T12). [1]

Internal abdominal oblique muscle

The internal abdominal oblique muscle is the intermediate layer of the 3 paired, flat abdominal muscles. It originates broadly from the anterior portion of the iliac crest, lateral half of the inguinal ligament, and thoracolumbar fascia. The internal abdominal oblique inserts on the inferior border of the 10th-12th ribs, the linea alba, and the pubic crest via the conjoint tendon. The muscle fibers of the internal abdominal oblique course upward in a superomedial orientation, perpendicular to the muscle fibers of the external abdominal oblique.

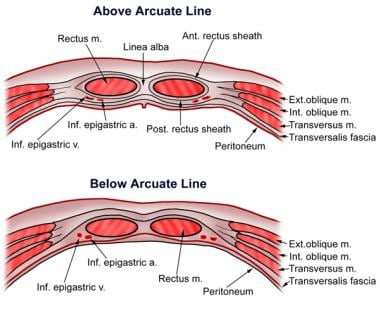

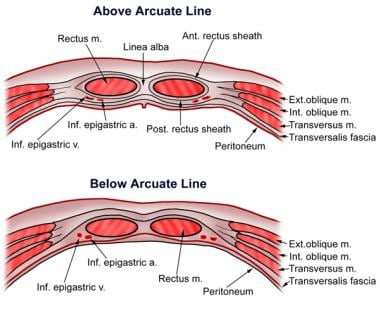

Like the external abdominal oblique, the internal abdominal oblique forms a broad aponeurosis that fuses into the midline and contributes to the rectus sheath. Superior to the arcuate line (see the image below), the internal abdominal oblique aponeurosis splits anteriorly and posteriorly to enclose the rectus muscle and helps form the rectus sheath. However, inferior to the arcuate line, the internal abdominal oblique aponeurosis does not split and only passes anterior to the rectus muscle as part of the anterior rectus sheath.

The arcuate line. a. = artery; Ant. = anterior; Ext. = exterior; Inf. = inferior; Int. = interior; m. = muscle; Post. = posterior; v = vein.

The arcuate line. a. = artery; Ant. = anterior; Ext. = exterior; Inf. = inferior; Int. = interior; m. = muscle; Post. = posterior; v = vein.

The inferior aponeurotic fibers of the internal abdominal oblique muscle course over the spermatic cord, through the inguinal canal, and the medial fibers fuse with the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle to form the conjoint tendon. [3]

The internal oblique is innervated in a segmental pattern by the anterior rami of the inferior 6 thoracoabdominal nerves (T7-T12) and first lumbar nerves (iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves).

Of note, all the neurovascular structures supplying the abdominal muscles run in the plane between the internal abdominal oblique muscle and the transversus abdominis muscle, except for the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. Initially, they lie on the anterior surface of the quadratus lumborum, then pass laterally into the plane between the transversus abdominis and the internal abdominal oblique. Above the anterior superior iliac spine, they penetrate the internal abdominal oblique to run between this muscle and the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle.

Transversus abdominis muscle

The transversus abdominis muscle is the deepest of the 3 paired, flat abdominal muscles. It originates on the internal surfaces of the 7th–12th costal cartilages, thoracolumbar fascia, anterior three fourths of the iliac crest, and lateral third of the inguinal ligament.

As with the other flat muscles, the transversus abdominis forms a broad aponeurosis that helps make up the rectus sheath before it fuses in the midline to the linea alba. Above the arcuate line, the transversus abdominis aponeurosis contributes to the posterior rectus sheath. Below the arcuate line, it is fused with the other flat muscles as the anterior rectus sheath. (See the image above.)

As its name implies, the muscle and aponeurotic fibers run in a transverse direction, except for the inferior most aponeurotic fibers. These fibers curve in an inferomedial direction to unite with the aponeurosis of internal abdominal oblique to form the conjoint tendon, which attaches onto the pubic crest and the pectineal (Cooper) ligament. The inferior aponeurotic fibers are fused to the underlying transversalis fascia, thus forming the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. A small triangular opening in this posterior wall is known as the deep or internal inguinal ring. It is at this opening that the spermatic cord is formed (by the ductus deferens, testicular vessels, and genital branch of genitofemoral nerve) and through which all indirect inguinal hernias develop. [4]

The transversus abdominis is innervated in a segmental pattern by the anterior rami of the inferior 6 thoracoabdominal nerves (T7-T12) and first lumbar nerves (iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves).

Rectus abdominis muscles

The rectus abdominis muscles are paired, long muscles that run just lateral to the linea alba in a vertical direction from the xiphoid process of the sternum and costal cartilage of the 5th-7th ribs to the pubic symphysis. These muscles function to tense the abdominal wall, flex the trunk, stabilize the pelvis, and aid in childbirth, defecation, micturition, and forced expiration.

Each muscle is divided along its course by 3 or 4 transverse fibrous bands known as tendinous intersections, which essentially divide the muscle into a series of interconnected muscles. This results in one's "abs" or "six-pack." The rectus muscles are contained within the rectus sheath, which is formed by the aponeuroses of the external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles.

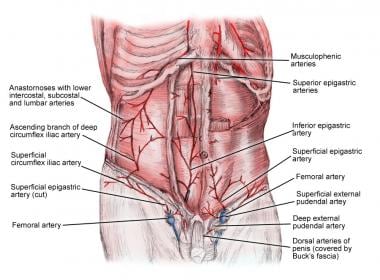

The rectus muscles have a dual blood supply. The superior epigastric artery and vein, which are direct continuations of the internal thoracic vessels, supply the superior half of the rectus muscles. The inferior epigastric artery and vein, which arise from the external iliac vessels just proximal to their passage under the inguinal ligament, supply the inferior portion of the rectus muscles and run superiorly until they anastomose with the superior epigastric vessels. In addition, there are numerous small, segmental contributions from the lower 6 intercostal vessels (see the image below). [3]

The rectus muscle is innervated in a segmental pattern by the anterior rami of the T7-T12 thoracoabdominal nerves. [1]

Pyramidalis muscle

The pyramidalis muscle is a small, triangular muscle that lies anterior to the inferior aspect of the rectus abdominis muscles. It originates at the pubic symphysis and attaches superiorly at the linea alba. This muscle functions to tense the linea alba and aid in midline stabilization. The pyramidalis muscle is generally considered insignificant in humans and is, in fact, absent in about 20% of the population. [3]

Arcuate line

Approximately midway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis is an arching, transverse anatomic line known as the arcuate line or the semicircular line of Douglas. Superior to this line, the anterior rectus sheath is composed of the fusion of the aponeuroses of the external abdominal oblique and the anterior leaf of the internal abdominal oblique aponeuroses. (The internal abdominal oblique aponeurosis splits to envelop the rectus muscle at this level.)

The posterior rectus sheath above the arcuate line is composed of the fusion of the posterior leaf of the internal abdominal oblique aponeuroses and the transversus abdominis aponeuroses. Inferior to the arcuate line, the anterior rectus sheath is composed of the fusion of all 3 muscle aponeuroses, and little or no posterior sheath exists, because only the thin transversalis fascia runs posterior to the rectus muscle (see the image below). [1, 5]

The arcuate line. a. = artery; Ant. = anterior; Ext. = exterior; Inf. = inferior; Int. = interior; m. = muscle; Post. = posterior; v = vein.

The arcuate line. a. = artery; Ant. = anterior; Ext. = exterior; Inf. = inferior; Int. = interior; m. = muscle; Post. = posterior; v = vein.

Linea alba

The linea alba is a dense, tendinous line created by the decussating aponeuroses of the external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles at the abdominal midline. Between the rectus muscles, it extends superiorly from the xiphoid, continuing inferiorly, where it passes superficially in front of the rectus muscles to attach to the symphysis pubis. Deeper fibers pass behind the rectus abdominis, attaching to the posterior pubic crest to create a triangular lamella known as the "adminiculum lineae albae." [2]

Above the umbilicus, the well-formed linea alba is wider, progressively narrowing and becoming more vague below the umbilicus to its inferior attachments. The midline laparotomy incision, dividing the linea alba, is one of the most common surgical approaches for abdominal exposure and the most common site of incisional hernia formation. [4]

Widening of the superior linea alba can cause a noticeable midline bulge known as a diastasis recti, or separation of the rectus muscles. Diastasis recti is a common and normal condition in newborns and is very common in women who have had multiple pregnancies.

Transversalis Fascia

The transversalis fascia is a thin layer of connective tissue lining most of the abdominal cavity between the posterior surface of the transversus abdominis and superficial to the extraperitoneal fat and peritoneum. Superiorly, this fascia continues with the inferior diaphragmatic fascia; inferiorly with the iliac and pelvic fascia; posteriorly with the thoracolumbar fascia; and laterally to the iliac crest.

Above the arcuate line, the transversalis fascia contributes to the posterior sheath along with the posterior leaf of the internal abdominal oblique and the transversus abdominis muscles (see the image below). Below the arcuate line, the transversalis fascia forms the posterior sheath alone. With attachments to the posterior margin of the inguinal ligament, it contributes to the formation of the femoral sheath, contributes the internal spermatic fascia, and becomes the only layer contributing to the inguinal floor. At the deep inguinal ring, the structures of the spermatic cord in males and, in females, the structures of the round ligament of the uterus pass through the transversalis fascia.

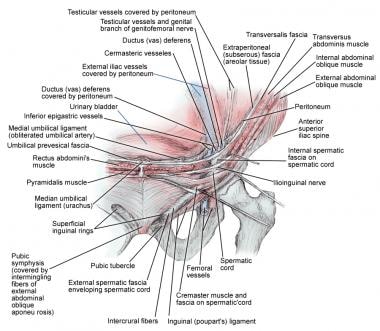

Inguinal Ligament

The inguinal ligament, or the Poupart ligament, is the thickened, inferior border of the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis that extends from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle and forms the floor of the inguinal canal (see the image below). At the medial aspect, some fibers divide posteriorly, attaching to the pectineal line to form the lacunar ligament or the ligament of Gimbernat, whereas other fibers extend superomedially to join the rectus sheath and linea alba, forming the reflected inguinal ligament. Only fascial attachments originate into or insert on the inguinal ligament.

The inguinal ligament also contributes to the inguinal (Hesselbach) triangle, forming the inferolateral border, whereas the epigastric vessels and the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle form the superolateral and medial borders. Direct inguinal hernias are seen within the triangle, whereas indirect inguinal hernias form lateral to the epigastric vessels. [5]

Inguinal Canal

The inguinal canal is a natural space created within the layers of the lower anterior abdominal wall just above the inguinal ligament (see the image below).

In the newborn period, the inguinal canal is short and lengthens over time to its final oblique position. In an adult, the canal measures approximately 3-5 cm and extends from the deep or internal inguinal ring to the superficial or external inguinal ring. The deep ring, formed by an opening in the transversalis fascia, corresponds to the middle of the inguinal ligament midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. The superficial inguinal ring is formed by an opening in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle, with the base at the pubic crest and a lateral and medial crus dividing and fusing by intercrural fibers, creating a triangular opening and lateral margin to the superficial ring.

The inguinal canal is formed superiorly by the lower edge of the internal abdominal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles; inferiorly by the inguinal and lacunar ligaments; and anteriorly by the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis. The lateral third of the anterior wall is further reinforced by a portion of the internal abdominal oblique. The posterior wall is formed by the conjoint tendon (the union of internal abdominal oblique aponeurosis and transversus abdominis aponeurosis) and the transversalis fascia.

The canal is reinforced medially by the internal abdominal oblique aponeurosis, whereas laterally, the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and the transversalis fascia form the wall in approximately 75% of individuals, with the remainder being formed only by transversalis fascia. This remains the most important boundary of the inguinal canal. Weakness or defects in the posterior wall may lead to formation of inguinal hernias. In males, the inguinal canal tends to be more developed, containing the spermatic cord and ilioinguinal nerve, whereas in females, it remains less developed and contains the round ligament of the uterus, in addition to the ilioinguinal nerve. [6]

-

Division of the abdomen into 4 quadrants.

-

Layers of the abdominal wall.

-

Muscular layers of the abdomen. Ext. = exterior; fasc. = fascia; Inf. = inferior; Int. = interior; m. = muscle.

-

The arcuate line. a. = artery; Ant. = anterior; Ext. = exterior; Inf. = inferior; Int. = interior; m. = muscle; Post. = posterior; v = vein.

-

Abdominal wall vasculature.

-

Inguinal anatomy.