Approach Considerations

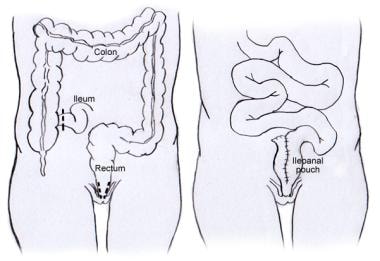

The ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) procedure (see the image below) is usually performed over two or three separate operations (ie, is usually a staged procedure). [11] In select circumstances and in select centers, restorative proctocolectomy is performed in a single operation. [12] The operative stages of the IPAA are usually separated by a period of 6-12 weeks (sometimes as long as 6 months).

In a two-stage procedure, the first stage includes proctocolectomy, IPAA, and creation of a diverting ileostomy; the ileostomy diverts the fecal stream, allowing for healing and maturation of the pouch. The ileostomy is then reversed during the second stage. In a three-stage procedure, the colon is removed during the first stage. The second stage involves removal of the rectum (proctectomy), IPAA, and diverting ileostomy. The third stage is reversal of the ileostomy.

The three-stage procedure is typically performed in ill patients with severe colon or rectal inflammation, usually as a result of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or infectious states. Removal of the diseased colon with diversion of the fecal stream from the remaining rectum avoids a lengthy operation and anastomosis in already compromised patients who are at higher risk for complications. After a period of time during which the patient recovers, proctectomy and IPAA are undertaken.

The procedure may be performed transanally [13, 14] as well as transabdominally.

Operative Procedures

Proctocolectomy

The IPAA procedure is performed in cases where the disease process involves the entire colon and rectum, necessitating complete surgical removal of these organs (ie, proctocolectomy). This can be accomplished either laparoscopically [15, 16, 17] or by means of laparotomy; robotic-assisted and hybrid approaches have also been described. [18] The small bowel and anus are preserved.

The first step in a proctocolectomy is to mobilize the colon by dividing its congenital peritoneal attachments. The omentum is dissected from the transverse colon, typically with an energy device. The terminal ileum is divided with a gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler. The colon mesentery, where the blood vessels and lymph nodes reside, is next divided in a stepwise fashion by using either an energy device or a clamp-and-tie technique.

The rectum is mobilized from the pelvis down to the level of the anus, with care taken to identify and preserve the pelvic nerves. Finally, the rectum is divided, ideally in such a way as to leave a cuff of rectal tissue no longer than 1-2 cm. This is done with a straight or curved thoracoabdominal (TA) stapler.

Total abdominal colectomy with end ileostomy

The colon is mobilized as described above. The junction between the colon and rectum (ie, the rectosigmoid junction) is identified and divided with a stapler. Pelvic dissection is avoided during this stage of surgery in order to minimize formation of pelvic scar tissue, which significantly increases the difficulty of subsequent rectal surgery. The colon mesentery is then divided and ligated.

An appropriate ileostomy site is determined, which is typically several centimeters to the right of and below the umbilicus and within the rectus abdominis. The ileostomy site should be chosen preoperatively, so that an area clear of any major skin folds and bony prominences with the patient in sitting, standing, and supine positions can be identified. A circular hole in the skin is made, and the underlying fascia is divided. The rectus abdominis is preserved in order to buttress the ostomy site, thereby decreasing the risk of hernia formation.

The ileum is brought through the fascial opening, either with the colon specimen or after first dividing the terminal ileum and removing the colon. The ileum is opened and sutured to the dermal layer of the ostomy site with a Brooke technique to create protrusion of the ileostomy. This allows improved fitting of an ostomy appliance.

Completion proctectomy

In the three-stage procedure, the colon is removed and an end ileostomy created during the first stage of surgery. During the second stage, the rectum is mobilized and divided as described above. This procedure is termed completion proctectomy. IPAA construction follows.

Creation of ileal pouch and anastomosis to anus

This portion of the procedure involves the creation of a pouch of ileum as a reservoir for stool and the connection, or anastomosis, of this pouch to the remaining anus. In the case of a three-stage procedure, the ileostomy is first taken down from the skin. The ileum is bent upon itself in the shape of a J, and the two bowel segments are connected in order to create a larger lumen and thereby a pouch. To do this, an opening is made at the bend of the small bowel, and a GIA stapler is inserted with one side of the stapler in each limb of the J.

The two bowel loops are connected with one or more firings of the GIA stapler in such a way as to create a reservoir that ideally is 15-20 cm long. The GIA insertion site is then anastomosed to the anus with an end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) stapler or with handsewn sutures between the pouch and the rectal cuff. Some studies have demonstrated improved outcomes when the stapled technique is used. [19] Occasionally, S- and W-shaped pouches are created rather than the more standard J-shaped pouch.

Diverting loop ileostomy

In both the two- and three-stage restorative proctocolectomy, a protective loop ileostomy is created in order to divert the fecal stream from the healing pouch. This is done by bringing a loop of small bowel proximal to the J pouch out through the skin in the right lower portion of the abdomen as described above. To mature the ileostomy, both the proximal and distal limbs of the eviscerated small bowel loop are sutured to the dermis.

Ileostomy reversal

The final stage of the two- and three-stage restorative proctocolectomy involves reversal of the diverting loop ileostomy. An incision is made around the ileostomy, and the ileostomy is dissected from the abdominal wall. Once it is free, the two limbs of the ileostomy are reconnected, often with bowel staplers. The bowel is returned to the abdominal cavity, and the ostomy site fascial incision is closed. The skin is either closed loosely or left open to heal by secondary intention.

A retrospective cohort study by Clancy et al assessed the effects of early (< 8 wk) ileostomy reversal against those of routine (8 wk to 116 d) reversal. [20] Complication rates were 17.4% and 11%, respectively. The complication rate in patients reversed early for stoma-related morbidity was significantly higher than that in the routine group (25.6% vs 11%), but the rate in patients undergoing scheduled early reversal was not (11.8% vs 11%). The likelihood of pouch anastomotic leakage was higher when reversal was performed early for stoma complications.

Complications

General complications of IPAA include those seen with any surgical procedure, such as the following:

-

Bleeding

-

Infections, such as wound infections, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and pneumonia

-

Heart complications

-

Blood clots

Complications specific to restorative proctocolectomy can be divided into those that occur in the short term and those that occur in the long term.

Short term

Short-term complications include pelvic sepsis and anastomotic leakage. [21] These serious problems may necessitate percutaneous drainage procedures or even emergency reoperation.

Long term

Fecal soilage or incontinence, intestinal obstruction, anastomotic narrowing, and sexual dysfunction are infrequent long-term complications of IPAA. More common long-term complications include female infertility and pouchitis.

Pouchitis occurs in as many as 50% of patients [22] ; typical symptoms include the following:

-

Diarrhea

-

Abdominal cramping

-

Fecal urgency

-

Tenesmus

-

Anorexia

-

Rectal bleeding (occasionally)

Pouchitis usually is readily treated with antibiotics. For chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis, some authors have found monoclonal antibody therapy to be effective. [23, 24, 25] Steroids have been used as second-line treatment, and other agents and interventions (eg, fecal microbiota transplant) have been tried in small studies. [26] A 2019 Cochrane review stated that the effects of antibiotics, probiotics and other interventions for treating and preventing pouchitis remain uncertain and that well-designed and adequately powered studies are needed to determine optimal therapeutic and prophylactic approaches. [27]

A study by Machiels et al suggested that the presence of specific microorganisms in the gut may be associated with a higher risk of post-IPAA pouchitis. [28]

A study by Klos et al suggested that obesity increases the risk of post-IPAA pouch-related complications. [9] However, a review by McKenna et al found no difference in pouchitis rates between obese and nonobese IPAA patients in long-term follow-up, though obesity did increase the complexity of the operation and was related to worse 30-day outcomes. [29]

Endoscopic therapies may be used to treat post-IPAA pouch strictures and leaks. [30] Techniques for treating pouch leaks have included clipping leaks at the tip of the J and endoscopic sinusotomy. Techniques for treating pouch strictures have included endoscopic balloon dilation, endoscopic stricturotomy, and endoscopic stricturoplasty.

Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) has been suggested as a possible means of reducing high stool frequency or fecal incontinence after proctocolectomy with IPAA. [31]

-

Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis.