Category: LCDs

SNK NeoGeo Pocket Color

This is my NeoGeo Pocket Color (NGPC), a short-lived handheld videogame system that the somewhat esoteric Japanese company SNK sold from 1999-2001.

I believe I found it at Village Thrift sometime well after the system was discontinued in the United States in 2000.

Village Thrift has a good habit of taking a lot of items that go together, like a NGPC and several games, and putting them together in a clear plastic bag. I remember finding it at their showcase, rather than the electronics section.

I’m also not sure if the scratch on the screen was there when I bought it or if that happened later.

The games that were in that plastic bag along with the NGPC were:

Sonic The Hedgehog Pocket Adventure, a Sonic the Hedgehog platformer:

Bust-A-Move Pocket, an entry in the well-known puzzle game series that resembles Bejeweled:

Baseball Stars Color, a fairly straightforward baseball game:

Neo Dragon’s Wild, a collection of “casino” games:

Metal Slug 1st Mission, a portable version of SNK’s Rambo-like side scrolling platforming shooter:

And finally Metal Slug 2nd Mission, the sequel to Metal Slug 1st Mission:

Oddly enough, there were no fighting games in that lot because that’s what SNK was known for and what enthusiasts wanted the NGPC for.

There are several neat and interesting things about the NeoGeo Pocket Color hardware. The first is that it has this tiny spec sheet for the display written above the screen.

You know, in case you ever need to look up it’s pixel pitch.

The screen on the NGPC can be difficult to see in all but direct sunlight and it can also be a pain to photograph. So, if my screenshots look odd, that’s why.

The need for very bright light in order to see the colors well was a problem with a lot of the color portable systems of this time period. I fondly remember the uncomfortable position I had to sit in to play Tetris DX on my purple Game Boy Color while hunched below a reading light that was attached to my bed. Penny Arcade memorably poked fun of the difficult to see screen on the Game Boy Advance in 2001. The rise of back-lit screens like the one on my Game Boy Micro finally alleviated this problem.

The unfortunate thing is that when you see screenshots of games from the NGPC and Game Boy Color from emulators you realize what beautiful colors those games were putting out and how the hardware made them almost impossible to see.

The NGPC has a unique 8-way joypad located on the left side of the console. This was the system’s most memorable feature and one that people would be wishing for on other portable game systems for years afterword.

Unlike the control stick you might see on an XBox controller this is a digital control pad, rather than an analog one. However, because it can move in eight directions it’s easier to point in a diagonal direction than a conventional cross-shaped D-pad like you find on Nintendo systems. SNK specialized in 2D arcade games that had sophisticated joysticks so it’s no surprise to find something like this on their portable system. The joypad has a really solid feel and makes a lovely clicking sound as you move it around.

On the back the NGPC curiously has two battery covers. The system uses two AA batteries to power the system and one CR2032 button battery to backup memory to save games and settings.

If the CR2032 dies you get this lovely warning message when you turn off the console.

When you turn on the NGPC the boot screen has an attractive little animation accompanied by a cute little tune.

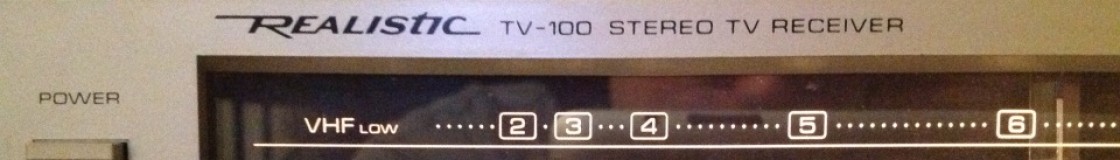

If you turn on the NGPC without a cartridge you get this menu screen that includes a calendar and (in silly Japanese fashion) a horoscope.

I can’t think of a videogame feature more utterly useless than a horoscope.

In order to explain the NeoGeo Pocket Color I have to tie together a few threads.

SNK is not what you would call a household name in the US but it was one of the titans of the Japanese arcade in the 1980s and 1990s. Their specialty was (and still is) was 2D fighting games. That is to say that the graphics are hand-drawn sprites that view the action from the side.

In 1990 SNK released the NeoGeo home console which for all intents and purposes was one of their arcade machines repackaged for home use. As you would expect it was outrageously expensive. The console itself (including a pack-in game) was $650 and games cost $200.

If you owned a Sega Genesis or a Nintendo SNES the NeoGeo must have seemed like some sort of mystical Shangri-La.

If you purchases a NeoGeo what you would have gotten for your obscene amount of money were perfect arcade games in the home. From the beginning of the home console market the fidelity of home console conversions of arcade games had been a constant problem. There were always compromises in animation, music, fluidity, and control sensitivity. Not so, if you were a NeoGeo owner. What you got was perfection.

But in the mid-1990s the market moved on to consoles such as the PlayStation and N64 that were built around 3D graphics. The arcades moved on too, and fighting games like the Tekken and Virtua Fighter series that were built on 3D graphics excited the public’s imagination.

SNK’s contemporaries like Capcom (whose Street Fighter series is one of the pillars of the 2D fighting genre) found ways to stay relevant by developing new series like Resident Evil while continuing their line of 2D fighting games. SNK didn’t and the NeoGeo became an expensive collector’s item.

Then, something possessed SNK to release a monochrome portable system called the NeoGeo Pocket in 1998 followed by the NeoGeo Pocket Color in 1999.

1999, when the NGPC came out, was a very strange time for portable videogames because it’s when the technological gap between the home consoles and portable consoles was at it’s peak. It wasn’t so much a technological gap as it was a chasm.

It’s funny how technology trends wax and wane over decades. Today, vast sums of R&D dollars are being spent on making components (especially CPUs and GPUs) for portable electronics faster and more power efficient. Intel’s new (Jone 2013) Haswell processors have marginal speed gains for desktop users but offer better battery life and less heat for mobile users. Across the industry from Apple to Samsung the effort is going into making better mobile devices.

Back in 1999, everything was different. Back then the money was being put into chips for devices like PCs and home game consoles that were plugged into the wall. We wanted faster devices and didn’t much care how much power they used or how much heat they put out.

In the home console market, the Dreamcast had just debuted, ushering in an era of more more refined 3D graphics that would lead to the PS2, XBox, and GameCube.

The Dreamcast was powered by a 32-bit Hitachi SH-4 RISC CPU and a PowerVR GPU that’s the direct ancestor of the GPU in today’s iPad and PS Vita.

Meanwhile in the portable realm the popular Game Boy Color was still based on an 8-bit CPU, technology that was solidly rooted in the game consoles of the 1980s. Very roughly this meant that the state-of-the-art home console was at least several hundred times more powerful than the leading portable console.

Battery life was the root cause of this gap. You could build a much more powerful portable system with a much more powerful CPU, much more RAM, and a higher resolution back-lit screen. But, it would have been heavy and had horrendous battery life. The marketplace thrashings that the Atari Lynx, the NEC TurboExpress, the Sega Game Gear, and the Sega Genesis Nomad received at the hands of the Game Boy throughout the 1990s were all clear proof of this reality.

Essentially those systems had tried to be to the Game Boy what the NeoGeo had been to the SNES and the Genesis, a far more powerful, far more expensive competitor. But, there was no place for that in the portable market.

The breakthroughs that would happen in the mid-2000s that allowed the revolution in portable computing devices simply had not occurred yet.

In 1999 the Game Boy Color sat at the sweet spot between battery life, weight/size, and cost. As a result, any serious competitor would have to have a comparable size, weight, cost, and battery life to the Game Boy Color and that precluded anything that was vastly more powerful. But it would also make it difficult for a serious competitor to differentiate itself from the Game Boy.

Technically, the NGPC was a 16-bit system and the Game Boy Color was just an 8-bit system but at these CPU speeds, with these amounts of RAM, and with these screens, the difference was negligible.

So the situation you had was that SNK must have felt that their background in 2D arcade games would be an asset in portable games, which were still totally dominated by 2D graphics even as the home consoles were putting out increasingly sophisticated 3D graphics. They probably also thought that as a company that specialized in fighting games they could build a portable game system suited to fighting games (with that gorgeous 8-way joypad) and exploit a market that Nintendo had ignored.

The problem was that 1998-1999 was an awful time for any company not named Nintendo to launch a handheld game console. From the earliest days of the Game Boy most of the best games had been essentially miniature versions of console games. The great games of the Game Boy from 1989 to 1998 include Super Mario Land 1 and 2, Metroid II, Legend of Zelda: Links’ Awakening, Kirby’s Dream Land, the Donkey Kong Land series and other games that basically would not have existed without their console counterparts.

Pokemon changed all of that in 1998 (in the US). Here was a game that had no console counterpart. Here was a game who’s popularity was strongly attached to being able to play the game against and with friends by connecting your Game Boys together. Here was a game that lent itself to consuming every available hour of a child’s day –on the school bus, on the playground, waiting at the doctor’s office, etc — like no game since Tetris.

NGPC had nothing comparable to Pokemon. At the time, the influence of SNK’s 2D arcade games was waning in American arcades so for the vast portion of the NGPC’s potential audience they had very little to offer. There were SNK enthusiasts who loved the NGPC and there were fighting game enthusiasts who loved the NGPC, but on the whole it didn’t make much headway in the American market. And that’s why mine ended up at a thrift store a few years later.

Sega Genesis Nomad

This is my Sega Nomad, the portable version of the venerable Sega Genesis videogame console, introduced in 1995. I don’t remember which thrift store I found it at, but it’s likely to have been the old State Road Goodwill, sometime in the early 2000s.

The Genesis is better known as “the Sega” (as in, “remember when were were kids and played Sega at your house?”) than by it’s real name. It was Sega’s one and only true hardware success.

By the end of the 1980s through a combination of quality first party games and tight control of third party publishers Nintendo had come to dominate the home videogame console market. The Genesis broke Nintendo’s near monopoly and setup the first great “console war” of the 1990s. Powered by the venerable Motorola 68000 CPU (which also powered the Apple Macintosh and is one of the great CPUs of all time) the Genesis was home to Sonic the Hedgehog, edgy fighting games, and popular sports games.

While they were riding high on the success of the Genesis in the early to mid 1990s Sega made some bizarre decisions about videogame hardware that damaged their relationship with consumers in the years to follow.

There are a lot of companies that you come to find out 20 years later had design concepts or prototypes for ideas that seemed really cool but in retrospect were probably best left on the drawing board. These drawings for Atari computers that never were and these Apple prototype designs come to mind. There are probably sound reasons why these things were never produced for sale. In Sega’s case, they actually produced some of their bizarre ideas and basically every one of them was either an embarrassing failure or was received with apathy by the public.

When you consider the numbers of consoles and hardware add-ons for consoles that Sega either produced or licensed to other companies it’s staggering to think how much hardware they produced in such short a time between 1991 and 1995:

- There were two versions of the Sega CD that added better graphics and a CD-ROM to the Genesis.

- The Sega CDX that combined the Genesis and the Sega CD into one semi-portable console.

- The Sega 32X add-on for the Genesis that added somewhat pathetic 32-bit CPUs to extend the Genesis’s lifespan.

- An attachment for the Pioneer LaserActive that combined Genesis and Sega CD hardware with a LaserDisc player.

- The JVC X’Eye that was a combination Genesis and Sega CD console licensed to JVC.

- The Sega TeraDrive that somewhat unbelievably combined an 286-based PC and a Genesis.

The Nomad is another one of these bizarre hardware ideas. The technology of 1995 could not provide the Nomad with a crisp screen, a manageable size, or anything that could be considered better than horrendous battery life.

Here’s the back of the Nomad. Notice there is no battery compartment but there are contacts for a battery accessory. You were expected to attach an external battery pack to the back of the Nomad to actually use it as a portable game system. Without the pack, the Nomad is already over 1.5 inches thick on it’s “thin” edge. I don’t have a battery pack so I can’t speak directly to what the weight and battery life are like with the pack installed, but you read phrases like “the low battery light told you when the Nomad was on” and “horrendous” to describe the battery life.

The Nomad’s screen, while much better at producing color at the Casio TV-1000 I blogged about in February, has some serious issues with ghosting. As you can imagine, this is an issue with games like Sonic the Hedgehog that have fast movement.

Oddly, the blurring actually does a good job at hiding the awful color dithering in Virtua Racing.

Apparently part of the cause of the Nomad’s notoriously poor battery life is the high voltage florescent backlight which also lights the screen in an uneven way.

If you had paid $180 for a Nomad in 1995 expecting a portable Genesis as advertised, you would have cause to be unhappy. In that respect, the Nomad was a failure.

The thing is though, is that if you just consider the Nomad to be a miniature, self-contained Genesis model, it’s pretty fantastic. The saving grace of the Nomad is that it has everything a Genesis has: An AV output, a second controller port, and a six button controller. I have several Genesis controllers and I dislike all of them. The buttons feel clunky and the D-pads feel mushy. The Nomad’s controls seem much sharper. I like the smooth, convex buttons on the Nomad much better than the rough, concave buttons on most Genesis controllers.

Now, you can’t use the Nomad with the 32X (because the AV output that’s necessary to connect to the 32X is covered up by the bulk of the 32X) or the Sega CD (because the Nomad lacks the necessary expansion port) but in all other respects it IS a Genesis. It uses the same AV cables and the same power brick as the Genesis Mark 2 model. If you want to collect Genesis cartridges and play them on a real Genesis but you lack space for a real Genesis in your residence, the Nomad is for you. You would do yourself a favor though, by plugging it into a TV (especially a late-model CRT TV).

One problem the Nomad shares with the Genesis Mark 2 is that the connection between the power input and the PCB board can become weakened causing the Nomad to randomly shut off or not turn on at all. My Nomad had this problem until my father opened up the unit and re-solderer the power input’s connection to the PCB. One of the five screws on the back of the unit is a security screw, so safely cut that screw post, which does not affect the structure of the case at all.

If you really, really want to use the Nomad as a portable Genesis there are mods available to help. One mod replaces the florescent backlight with an LED for significantly improved battery life but otherwise stock appearance. Another mod replaces the mid-90s vintage LCD with a modern LCD for improved screen clarity.

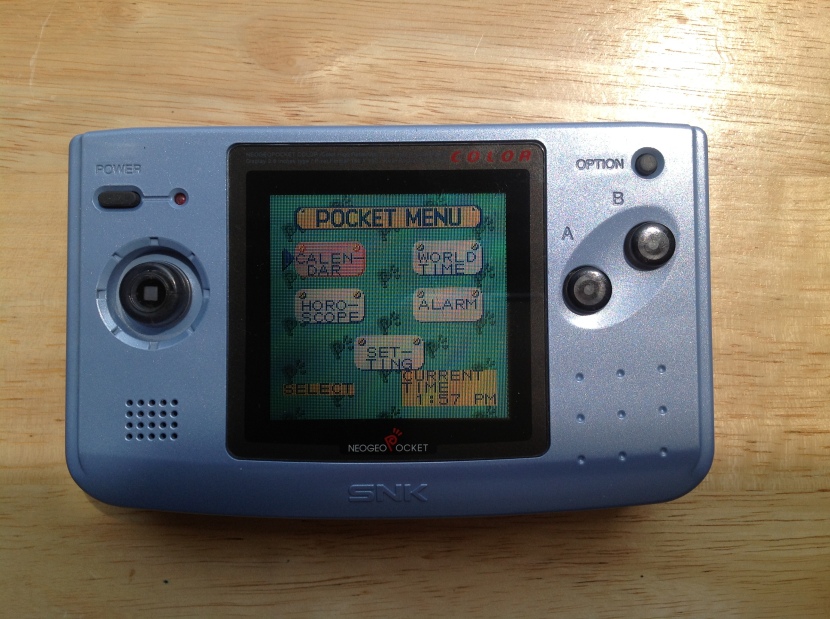

Apple PowerBook G3 (Wallstreet II/PDQ)

There was a period in the late 90s and early 2000s when finding old computers, especially Macintoshes was a regular occurrence at the local thrift stores. I’ve basically been a Wintel guy since the mid 90s but the collectability of old Macs piqued my interest. These were not generic beige boxes; Macs had well-documented stories. I quickly accumulated a Mac 128K (that had been upgraded to Mac 512K specs), a Mac Plus, a Mac SE, a Quadra 700, and a Mac LC (I still have some of these machines and plan to do posts on them someday). However, there came a point in the mid-2000s when these machines stopped showing up at thrift stores.

Today, it has become really difficult to find classic computers at thrift stores. Partly I think this is because the larger stores such as Goodwill are concerned about the privacy and licensing issues of selling old PCs. They have to be concerned with with the previous owner’s data and would rather recycle the PCs than deal with wiping them properly and the license hassle of reinstalling software for resale. I think it’s also because the smaller stores don’t understand there is a collector market for vintage PCs and they think that older computers are too difficult to sell. People alo probably only keep one or two generations of old computers in their house so in many cases they’ve already trashed most of the really vintage stuff. The good old days I experienced in the late 1990s and early 2000s have come and gone. As a result, I have decided as a general policy that if I see an interesting computer at a thrift store I should pick it up because I never know when I’ll see one again.

However, for whatever reason I never saw Macintosh laptops at thrift stores, even in the good-old-days.

Imagine my surprise one day in 2011 when I saw this lovely Apple Powerbook G3 sitting on a pile of old furniture at the Abbey Anns off the Circle in Tallmadge.

It was really dirty and covered in stickers but as far as I could tell it was complete. There was no power supply included and the battery was clearly dead so I ended up buying it for about $15 without knowing if it worked. After buying a knock-off power supply from eBay I was amazed to find that it indeed still worked! With that said the hard drive now makes some awful sounds and sometimes takes several attempts to start so it could probably die at any time.

Going from this badge I believe this Powerbook G3 to be the “Wallstreet II/PDQ” model as that’s the model that came with the 266MHz processor while still having the colored Apple badge.

The Apple System Profiler says this machine has 128MB RAM, so someone probably upgraded it at some point.

This machine because is clearly from a very transitional period for Apple shortly after Steve Jobs returned in 1997. On the lid is the new transparent/white Apple logo and on the inside is the color striped Apple logo they had used since the late 1980s (also my favorite version of their logo). The machine is powered by the Power PC G3 processor that would also power the first iMacs (the first stellar success that Jobs would have after returning to Apple) but the back of the machine reveals an Apple Desktop Bus port and a DIN-style serial port that would have been more familiar in older Macs from about 1986 onwards. You can immediately tell from the dark gray exterior that this is a Powerbook descended from the first Powerbooks in the early 90s. And yet, the generously large screen and the still-good-by-today’s-standards touchpad remind me off today’s Apple laptops. This is a computer with its feet in two eras in Apple history.

This Powerbook G3 is also a computer that feels like it represents the best of the era of Apple that was soon to be wiped away by brushed aluminum. The Apple of today produces really well engineered computers but they have turned brushed metal into the new beige. They want computers to look like fashionable Braun radios. Today’s Apple would never put a processor badge on their computers or build a laptop with two docking bays and a removable battery. We will surely never see a return to this philosophy, but this machine is a nice reminder of what once was.

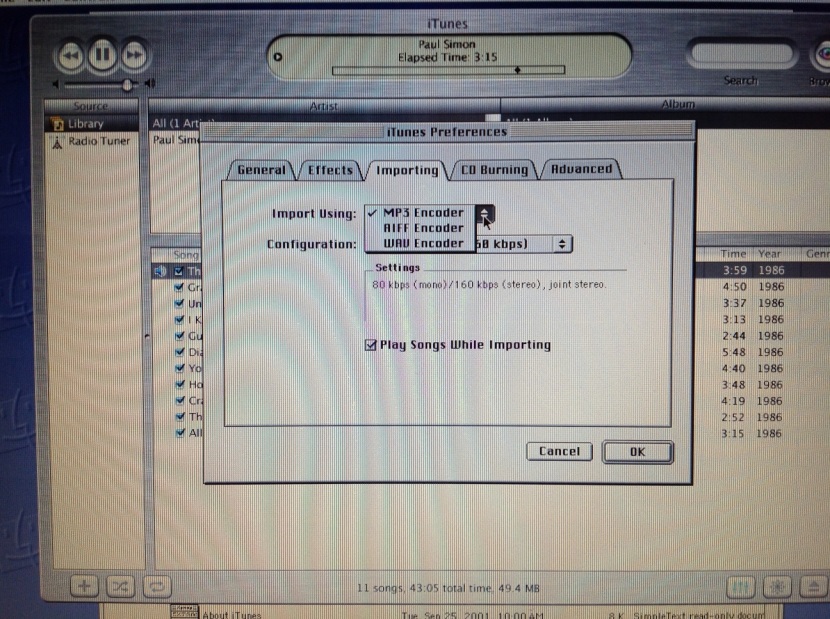

There was a wealth of old software on this Powerbook G3 including Mac OS 9.2.2, iTunes 2, Mozilla 1.0, Netscape, Internet Explorer 5 for Mac, and some Adobe software including Photoshop.

Seeing this ancient version of iTunes was particularly interesting for me because I use iTunes today on Windows.

It’s hilarious to see iTunes without AAC encoding.

As a die-hard Firefox user since 2003, I was also curious to see what Mozilla 1.0 looked like.

I also like silliness so here is the Goodtimes video from the Windows 95 CD being played on the Powerbook G3.

I have quite a large collection of old software (which I will get to in future posts) but I was surprised to find that I had very little that will run on late model classic Mac OS. I tried SimCity 1.4c, but that complained about requiring 256 color mode and I wasn’t too keen on entertaining that foolishness.

I did remember however, that one of my favorite games from the late 1990s, Close Combat: A Bridge Too Far, came with a Mac OS version on the same disc as the Windows version (surprising for a Microsoft published game).

Here is what the installer looks like.

The game doesn’t run badly and is surprisingly playable with the trackpad.

Looking at this Powerbook is kind of like looking at an Art Deco building and thinking about the 1930s. The swooping curves of this machine remind me of the dynamism right before the Dot Com crash when the promise of all of that “multimedia” bunk from the early 90s was finally going to pay off with the Internet. It also reminds me that the Apple of the 1990s that almost died also died with this machine and that the Apple of the 2000s that changed the world in some ways was born with this machine.

Casio TV-1000

We’ve all become accustomed to “the smartphone stare”. You know, when someone is hunched over their smartphone, oblivious to the world around them, bathed in the glow of their smartphone’s screen. I admit, I can be found in this state several times on the average day.

The magic of the “smartphone stare” is the magic of the personal electronics revolution: It’s the way that an electronic device can be made small enough that you can use it without sitting down. You don’t need a room in your house for it and you don’t need any special furniture. You just pull it out of your pocket and commune with a piece of electronics. When a piece of electronics can come with you anywhere you go and can be used at practically any time it becomes something more intimate.

The “smartphone stare” might seem like a recent phenomenon, but videogame enthusiasts will recall that for them it basically started in 1989 with the Game Boy and Tetris, which for many people was the first really killer portable gaming experience.

But, even before the Game Boy a handful of early adopters could be found basked in the glow of their handheld TVs.

I have a particular affection for the various attempts to make a usable handheld TV in the 1980s. For one, I love the 80s styling. They’re like little jewel boxes of 80s chic. For another, these devices are relatively easy to find and even easier to store. Also, these devices were pushing the boundaries of what was possible technologically, and I respect that. Finally, I’m fascinated by how at the time these were esoteric luxury devices and today they are basically semiconductor trash.

Of the vintage handheld TVs I own the Casio TV-1000 is my favorite. This was one of Casio’s first attempts to make a color LCD handheld TV.

I found it at the Village Discount on State Road in Cuyahoga Falls with its original box, instructions, and warranty card.

While it does have a backlight it also has an interesting feature where you can open up this door in the back to allow light in, as a way to conserve battery power.

The part that folds down there is actually the battery compartment, which is smart because it gives that section some heft to weight the set while it’s folded down. The interesting thing is that with that part open you can see the innards of the backlight diffuser, which is located at the bottom of that angled transparent section, and how it’s meant to distribute light across the screen evenly.

Image quality, as one would expect from a mid-1980s passive LCD is atrocious. My understanding is that the TV-1000 was an attempt to produce a more affordable color micro TV than it’s contemporaries the Epson ET-10 and the Seiko T-102 and as a result it uses a passive LCD rather than an active LCD. I can’t say I’ve ever seen a passive LCD screen that was ever any good.

Here I am trying to tune in one of the last low-power analog TV stations in the area, WAOH-LP (oddly enough, they were showing a black and white program).

Notice the onscreen blue bar on the side with the red hash mark on the right side of the display. In order to tune the TV-1000 you would select VHF or UHF and then press the up or down channel button once so that it would start scanning for a channel. The red mark shows what channel it’s currently tuned to. The scanning process makes it difficult to tune in a marginal station because often it will scan right past. I would vastly prefer a manual tuning knob like the CRT Sony Watchman sets from the same era. But I suppose at the time this type of tuning seemed more high tech.

The TV-1000 also has a standard RCA 1/8th inch AV input, which is useful in the post analog TV doomsday. Use red/right for video and white/left for audio.

Here is Super Mario World on my Yobo FC Twin (which I shall discuss in the future). As you can see, the TV-1000’s color reproduction is awful, but that’s the reality of mid-80s passive LCDs. The sound however, is loud and crisp.

Right now the TV-1000 is the only 1980s-vintage LCD handheld TV I own, but I’m always on the lookout for others. I do, however, have several micro CRT handheld TVs from the 1980s: A functional Sony Watchman FD-10A, a functional Sony Watchman FD-30A, and a non-functional Panasonic TR-1010P.